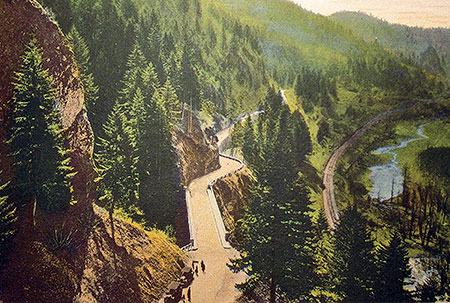

Mount Hood from Historic Bennett Pass Road

One of the many misconceptions about our national parks is that visiting means contending with the masses along crowded paved roads, with the only chance for solitude limited to trails that are beyond the abilities of many visitors, including the elderly, those with limited mobility or young families.

But the truth is that our national parks also feature some of the most stunning primitive backroads for those looking for a more accessible way to get off the beaten track.

One of the most spectacular is the Titus Canyon Road in Death Valley National Park, and the concept behind Titus Canyon has stuck in my mind since I first visited the park in the early 1980s.

One-Way Concept

Titus Canyon: Yogi Bear does not drive here!

Titus Canyon Road begins east of Death Valley, at the near-ghost town of Rhyolite, climbs over 5,000 foot Red Pass, then begins a spiraling descent of nearly a vertical mile as it enters the increasingly narrow gorge of Titus Canyon. When the road finally emerges near sea level, from the east wall of Death Valley, the floor of Titus Canyon has shrunk to a point that two cars would not be able to pass.

One-way trip to heaven… in Death Valley

This is where the genius of Titus Canyon Road comes in. The Park Service has designated this a one-way road, with traffic allowed only in the direction of Death Valley.

The physical constraint at the lower end of Titus Canyon is the determining factor, to be sure, but the broader effect is that one-way traffic provides a remarkably relaxing experience in which visitors can focus on the scenery, not dodging oncoming traffic. The one-way design also negates driving through clouds of dust from oncoming vehicles, a notable benefit on primitive roads.

Titus Canyon narrows (and my 1980s Honda Civic, back in the day)

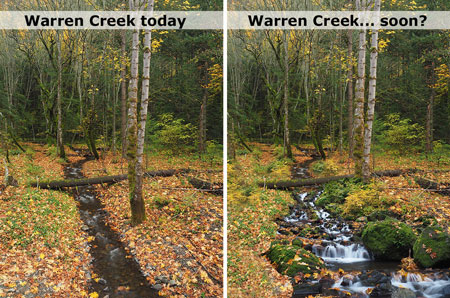

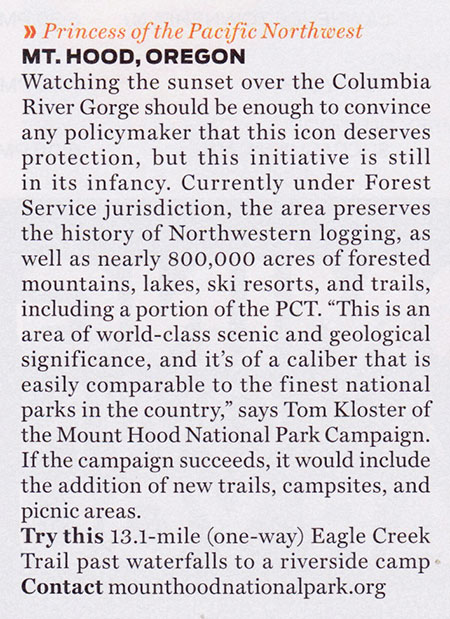

So, how does this relate to Mount Hood? Part of the Mount Hood National Park Campaign concept calls for repurposing some of the thousands of miles of failing, obsolete logging roads in the Mount Hood National Forest into scenic backroads or trails for hiking or biking.

Most of these roads were constructed during the industrial logging heyday from the 1950s through the late 1980s, and were solely designed around clear cuts, not a concern for the respecting landscape or taking in the scenery.

But a few of these roads date back to an earlier era, when the first few roads connected major destinations in the new Mount Hood National Forest in the 1920s and early 1930s. These roads were often built without machinery, and subsequently follow the contours of the land in a way that roads from the industrial logging era rarely do.

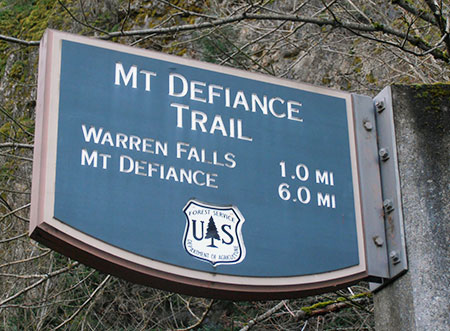

Historic Bennett Pass Road

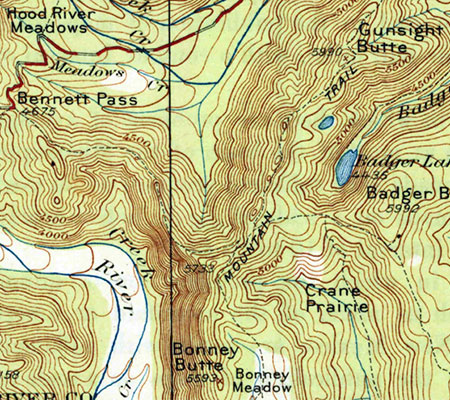

Views into the remote Badger Creek Wilderness abound along historic Bennett Pass Road

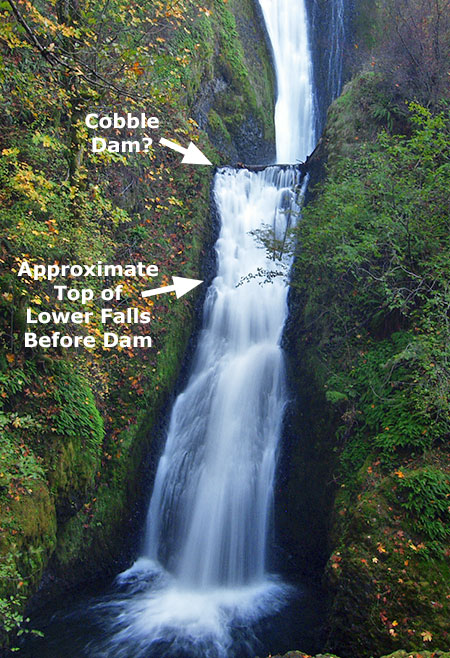

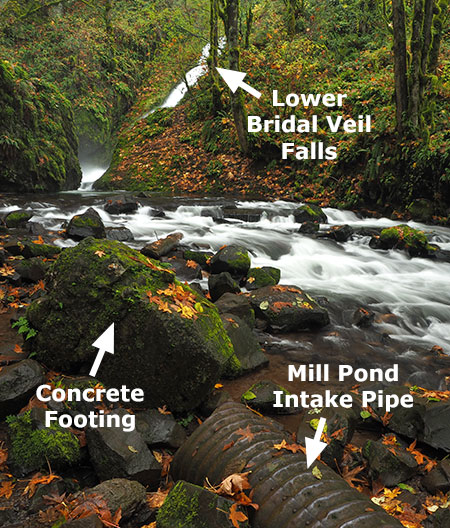

One such historic forest road connects High Prairie and Lookout Mountain, located 8 miles due east of Mount Hood, to Bennett Pass, on the southeast shoulder of the mountain. For travelers of the Mount Hood Loop Highway, the old route follows the high ridges that form the wall of the East Fork Hood River valley, as you descend from Bennett Pass toward Hood River.

Today, the historic Bennett Pass Road is a bumpy, often grinding minefield to navigate. It’s hard to imagine that it was the main forest route when it was built, but it still passes some of the finest scenery in the area along the way, and has the potential to be an exceptional scenic backroad.

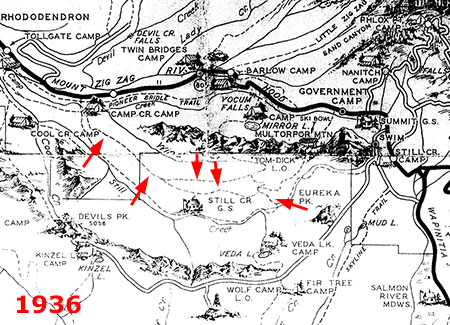

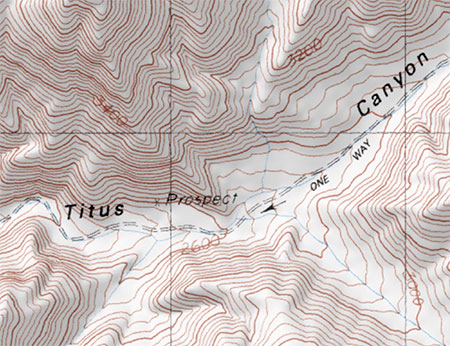

1920s map when the future Bennett Pass Road was still just a “mountain trail”

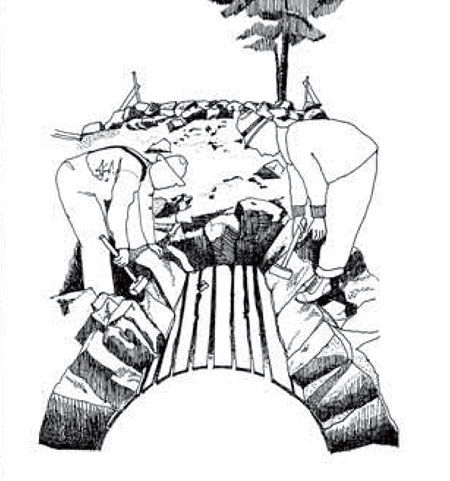

When it was built in the early 1930s, the historic road followed the route of an early forest trail along the ridge that connects Bennett Pass to a Forest Service guard station that once stood at High Prairie (if you know where to look, you can still find the ruins). The road was built by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) in the early 1930s by crews based in Camp Friend, located to the east of Lookout Mountain, and just south of the town of Dufur. The Camp Friend crews also built several lookouts in the area and the historic road to Flag Point.

Today, the historic Bennett Pass Road serves as the western boundary for the Badger Creek Wilderness and the northern boundary for the White River Unit of the Mount Hood National Recreation area. This easy proximity to both of these protected areas brings a string of fine trail opportunities along the route for exploring nearby viewpoints, lakes and meadows on foot.

Boulder Creek Valley and Echo Point in the White River Unit of the Mount Hood National Recreation Area from the historic Bennett Pass Road

The northern section of the historic Bennett Pass Road, from High Prairie to Dufur Mill Road, was bypassed and decommissioned in the late 1980s when the newer, gravel-surfaced road to High Prairie was constructed. For the purpose of the Bennett Pass Historic Backroad concept, this newer section is included in the proposal, with the Dufur Mill Road junction serving as the starting point for the backroad tour and Bennett Pass as the end point.

How would it be different?

How would the Bennett Pass Historic Backroad differ from what is on the ground today? First, it would be one-way from High Prairie to Bennett Pass, the historic section of the original road that still survives. Like Titus Canyon, this portion of Bennett Pass Road has a few spots where passing an oncoming vehicle would by physically impossible – notably below Lookout Mountain and along a notorious stretch etched into a cliff known as the Terrible Traverse.

Leaving the Terrible Traverse en route to Bennett Pass

But like Titus Canyon, the purpose of the one-way tour is mainly to allow for a greater sense of remoteness and ability to truly appreciate the rugged scenery along the way.

Second, the concept of a scenic backroad also includes ADA-compliant picnic and restroom facilities along the way to ensure that all visitors can enjoy the tour. As our population ages and our society becomes more socially inclusive of those with limited mobility, providing accessible alternatives for exploring our public lands has become a critical, largely unmet need.

Some of these facilities are already in place at existing trailheads and could be made accessible with modest improvements. Other spots along the route would need these basic improvements.

Enjoying Mt. Jefferson and views into the Badger Creek Wilderness at 10 mph along the historic Bennett Pass Road

Finally, a 10-mph speed limit would ensure that the proposed Bennett Pass Historic Backroad tour remains focused on users looking for a relaxing, scenic way to enjoy the area. This means that OHV users accustomed to traveling at greater speeds would need to find other places to make noise and disturb other forest visitors — and besides, the Forest Service has set aside areas for OHVs elsewhere in the forest.

The faded (and assassinated) top sign warns passenger vehicles from venturing onto the historic Bennett Pass Road

Today, it’s hard to get much beyond 5-mph in many sections of the Bennett Pass Road due to a profound lack of maintenance, so a light upgrade to the surface and periodic maintenance is part of the concept. In the 1980s, I navigated Titus Canyon Road in a Honda Civic, and there’s no reason why a better maintained Bennett Pass Road couldn’t accommodate passenger cars traveling at 10 mph. That’s part of being inclusive, after all.

Signage is deficient or completely absent along much of the route today, so the backroad concept also calls for improved directional signage and occasional interpretive signage along the tour, as well. Interpretive signage could be as simple as mileposts that link to a downloadable PDF or podcast describing the rich natural and cultural history of the area.

The Bennett Pass Historic Backroad Tour

The full tour covers just over 14 miles, but at 10-mph with a few stops along the way, the Bennett Pass Historic Backroad tour would take the average family two or three hours to complete. Add an hour on each end to reach the tour from Portland, and this would make an exceptional choice for urban visitors looking for a new way to explore Mount Hood country.

Here’s a tiny map of the concept:

But by all means, please click here for a very large version of the map to see the details that make up this proposal.

Tour Description

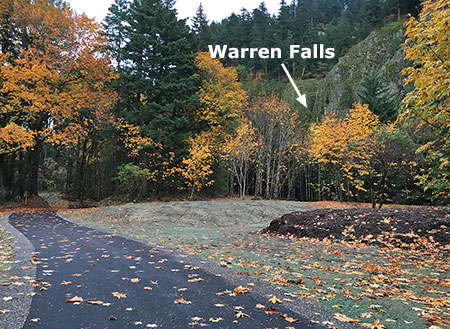

0.0 to 2.8 mi. – Dufur Mill Road to Sunrise Rocks – The tour starts at gravel Lookout Mountain Road (Road 4410) where it begins on paved Dufur Mill Road (Highway 44), north of Lookout Mountain. This is the section of the route built in the 1980s to bypass a (now abandoned) portion of the historic road.

After climbing through forest and passing pretty Horkelia Meadow, this segment ends at the mostly unknown Sunrise Rocks, a fine, currently undeveloped picnic spot with a commanding view of Mount Hood, across the East Fork Hood River valley.

The sprawling Mount Hood view from semi-secret Sunrise Rocks

The Bennett Pass Historic Backroad concept (see map) also calls for a new trail in the area, from the Little John winter recreation area to Sunrise Rocks, providing another way to enjoy this overlook for hikers looking for a challenge and a year-round purpose for the Little John trailhead.

Sunrise Rocks from the Little John trailhead and parking area… someday a trail from here?

2.8 to 4.9 mi. – Sunrise Rocks to High Prairie – after taking in the view at Sunrise Rocks, the route continues for another 2 miles along the newer road section to High Prairie, a major destination for hikers and equestrians. Families looking for a picnic or short hike can explore the sprawling meadows here, or take the longer 5-mile loop to the airy summit of Lookout Mountain, where the view stretches up and down the Cascades and into the high desert country of Eastern Oregon.

Acres of subalpine wildflowers and a maze of family-friendly trails await at High Prairie

4.9 to 7.2 mi. – High Prairie to Gunsight Ridge – two-way travel ends at High Prairie in the historic backroad concept, and from this point forward the tour would be one-way toward Bennett Pass along the surviving, original section of the historic Bennett Pass Road. The segment of original road from High Prairie to Gunsight Ridge is the most breathtaking on the tour, with huge views of Mount Hood and exposed sections where drivers will be gripping the wheel — and taking in the views.

Sweeping Mount Hood views abound where the historic Bennett Pass Road skirts Lookout Mountain

Several scenic pullouts are located along this section, as well as a major trailhead at Gumjuwac Saddle, with trails heading in five directions! Hiking options from the saddle include longer trips to Badger Lake and Lookout Mountain, or the nearby Gumjuwac Overlook, just 0.8 miles from the saddle.

Mount Hood after an early autumn snow from the Gumjuwac Overlook

The proposed Gunsight Ridge picnic area would be located at a large pullout above pretty Jean Lake, with access to the Gunsight Trail. Jean Lake can be visited via a family-friendly 0.6 mile trail that descends to the lake.

Pretty Jean Lake is a short forest hike from the historic Bennett Pass Road

7.2 to 9.0 mi. – Gunsight Ridge to Camp Windy – the short drive from Gunsight Ridge to Camp Windy is just below the ridge crest, with frequent views into the Badger Creek Wilderness, and later, into the White River unit of the Mount Hood National Recreation Area.

Expansive meadows at Camp Windy roll down the slopes of Gunsight Ridge

Modest picnic facilities and a vintage toilet already exist at Camp Windy, a lovely mountainside meadow, but new facilities would be needed as part of the scenic backroad concept. A short spur road here provides access to the Badger Saddle trailhead, and the 3.5-mile round trip hike to Badger Lake.

Mount Hood from the Gunsight Ridge Trail

9.0 to 10.1 mi. – Camp Windy to Bonney Junction – From Camp Windy, the historic road continues to a 3-way junction with Bonney Meadows Road (Road 4891). The historic backroad concept calls for the Bonney Meadows route to function as a 2-way facility, allowing access to the Bennett Pass Historic Backroad at its midpoint, and for Bennett Pass visitors to make side trips to Bonney Meadows and Bonney Butte, just off the Bennett Pass tour.

Peaceful Bonney Meadows with Mount Hood peeking over the ridge

Bonney Meadows already has a rustic campground perfect for picnics and exploring the nearby meadows. Families looking for something more challenging can make the 4.5 mile round-trip hike to exceptionally scenic Boulder Lake, or try a shorter hike to Bonney Butte, known for its raptor surveys. Bonney Meadows also has several developed campsites, so families could opt to camp here, midway through the tour.

Lovely Boulder Lake

10.1 to 12.4 mi. – Bonney Junction to Newton Clark Overlook – from Bonney Junction, the historic Bennett Pass Road turns abruptly north and descends briefly before arriving at a catwalk section of road carved into the crest of the ridge. Here, the tour passes the Terrible Traverse, marked by an extraordinary rock gateway cut by the early road builders. This is the Titus Canyon equivalent for the Bennett Pass Road, as there is no room for passing (or error) along this section!

The dramatic gates to the Terrible Traverse

Just beyond the traverse, the road drops to a saddle with an excellent view of Mount Hood at the proposed Newton Clark overlook and picnic site.

The Newton Clark Glacier and its enormous moraine from the proposed Newton Clark overlook

This spot is also one of several backcountry lodge locations proposed in the Mount Hood National Park Campaign to allow for Euro-style chalet-to-chalet trekking. These modest lodges would be rustic and quiet, along the lines of Cloud Cap Inn, and open year-round to also serve Nordic skiers and snowshoers.

It turns out the Hood River County Sheriff digs the Newton Clark overlook, too (Courtesy Hood River Co.)

12.4 to 14.2 mi. – Newton Clark Overlook to Bennett Pass – from Newton Clark Overlook, the remainder of the route continues along the ridge top through handsome stands of noble fir to the large trailhead and parking area at Bennett Pass, ending the tour.

What would it take?

While some of the proposals featured in this blog are notably ambitions, this one is pretty simple, and could be accomplished in the near-term. The Forest Service would need to do some grading, add some gravel in some sections and step up maintenance of the historic Bennett Pass Road. Picnic and toilet facilities would need to be added in a few spots and new signage to help visitors navigate and appreciate the tour would be needed.

Wildflowers line the historic Bennett Pass Road in summer

Establishing a one-way route would be a taller order for the Forest Service, but there are already a few limited one-way routes along forest roads, so the idea is not without precedent. One obvious exception to a one-way rule is for emergency access, of course, but other visitors would probably appreciate the peace of mind in knowing they won’t meet another vehicle at the blind curve midway along the Terrible Traverse!

How to visit?

The good news is that you can visit the proposed Bennett Pass Historic Backroad today with a few considerations in mind:

- The road is generally only open in summer, from mid-June through early October. The best time to visit is in July, when wildflowers are blooming throughout the tour, and the worst time is after heavy rain, when a few muddy sections might just swallow your vehicle.

- Parts of the historic portion of the road are very, very rough. Until a Bennett Pass Historic Backroad brings some surface improvements and periodic maintenance to this old route, plan on a slow, sometimes jarring ride that will test your nerves, tires and suspension. High clearance vehicles with AWD or 4WD, only!

This collage of scraped rocks on Bennett Pass Road is mute testimony to the folly of taking a passenger vehicle there – don’t try it!

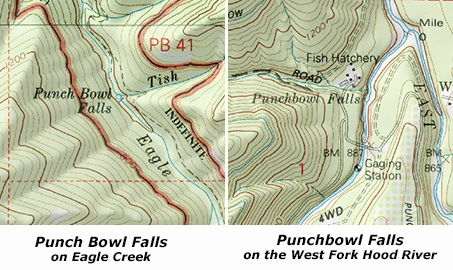

- The roads are poorly signed, so you’ll need a forest map. I recommend the National Geographic map for Mount Hood National Forest in their Trails Illustrated series. Never trust a GPS device or smart phone to navigate forest roads!

The author hanging out on the historic Bennett Pass Road

With these precautions in mind, the old Bennett Pass Road is fun to explore and always un-crowded.

Take it slow and enjoy the ride!