The Columbia River Gorge is so rich with natural beauty that it’s pretty hard to pick favorites. Yet, when it comes to graceful waterfalls cascading through verdant, rainforest canyons, Oneonta Creek is near the top of my list. A previous article on this blog presented a new vision for managing access to stunning Oneonta Gorge and restoring the historic Oneonta Tunnel. This article examines Oneonta Canyon above the Oneonta Gorge, where more waterfalls and rugged beauty brought thousands to the trails here before the 2017 Eagle Creek Fire.

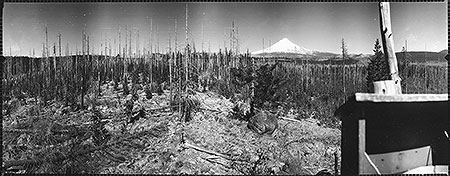

The fire has since changed the Gorge landscape for most of our lifetimes, and the forest is just beginning a post-fire recovery cycle that has unfolded here countless times over the millennia. But while the starkness of the burned landscape is something that we are still adjusting to, the fire gives us a once-in-century opportunity to rethink and rebalance how we recreate in the Gorge.

Oneonta Creek experienced some of the most intense burning during the fire, and almost none of the dense forest canopy survived, and still the forest has already begun to restore itself. What can we do to restore our human presence at Oneonta in a way that will be sustainable for the next century, leaving a legacy for future generations like the one that we inherited?

Before the 2017 Fire: Signs of Stress

The spectacular scenery along the Oneonta Creek was already drawing huge, unsustainable crowds of hikers well before the Eagle Creek Fire roared through Oneonta Canyon, and the visible impacts were everywhere. Some of the impact was on the human environment, including the very trails and bridges that brought hikers into Oneonta Canyon. And some of the impact was on the land, itself, with hikers straying from developed trails to create destructive social paths and shortcuts in many spots. These informal trails had become badly eroded, often undermining the main trails, themselves.

One place where these impacts escalated alarmingly in the years before the fire was the lower footbridge on Oneonta Creek, located just above Oneonta Falls and just below Oneonta Bridge Falls. As shown in the photo above, crowds of hikers had carved a new path to a pool in the creek at the west abutment of the bridge, stripping away fragile vegetation and filling the pool with eroded debris.

The photo below shows how this social path has not only destroyed the thin layer of soil and forest understory on the slopes of Oneonta Creek, but was also undermining the main trail, itself, which was gradually sliding down the slope.

Even the lower Oneonta footbridge was in trouble before the fire. The Forest Service began posting a warning on the bridge a few years before the fire limiting it to one hiker at a time, yet another reminder of the serious disinvestment we have been making in our Gorge trails for the past thirty years. The rapid growth in visitors during this same period only increased the impact on structures like this, which were long overdue for repair or replacement.

Meanwhile, at the east end of the lower Oneonta Bridge, curious crowds had pushed a new social path upstream, past Oneonta Bridge Falls (below). Social paths form when hikers head off-trail in search of a new viewpoint or water feature. When more hikers the steps of the first, the increasing foot traffic gradually formalizes social until they become hard to distinguish from legitimate trails — except that they are rarely “built” in a way that is sustainable, and often bring serious harm to the landscape.

Meanwhile, things were getting worse on the east side of the lower Oneonta Bridge, too, where hikers had cut the short switchback just above the bridge (below) to the point that it began collapsing before the fire closed the area to the public. Why do people do this? Mostly, it’s ignorance, inexperience and overcrowding, and often by children who are not getting needed guidance from parents on why this is not okay.

Heading beyond the lower Oneonta bridge, another major social path had formed on the west side of the creek (below), where hikers had created a long shortcut directly down the canyon slope where a long switchback exists on the main trail. The damage here was obvious and quite recent when this photo was taken about 18 months before the fire. When social paths become this prominent, the damage begins to spiral, with new or inexperienced hikers mistaking them for a legitimate route, and further compounding the problem with still more foot traffic. The overcrowding on the Oneonta Trail only added to the spiraling effect.

While hikers were causing the bulk of the impact before the fire, Mother Nature was busy in Oneonta Canyon, too. The photo below was taken after the 2017 fire, and reveals a major landslide that began moving years before the fire. The slide extends from Oneonta Creek (where it has left a pile of trees and debris visible in this photo) to the cliffs well above Oneonta Trail. A fifty-yard section of the trail was erased by the slide, with several efforts in the years just before the fire to stabilize a new route above the old trail.

Here’s a view (below) of the landslide looking downhill toward Oneonta Creek from where the original Oneonta Creek Trail was once located. The big trees still standing in the path of the landslide in this view were burned in the fire, which will further destabilize this slope and allow the slide to accelerate in coming years.

When the original section of the Oneonta Trail was swept away by the landslide, the Forest Service built this set of stairs (below) to a new crossing of the slide, about 30 yards uphill from where the old trail had been.

This photo (below) shows the new, temporary crossing of the slide as it existed before the fire, but volunteer trail crews visiting the Oneonta Trail earlier this year report that this temporary route has also become eroded since the fire. The continued instability of the landslide raises real questions about whether a safe route can be maintained here in the near-term.

Landslides like this are an ongoing part of the Gorge geology, but in this case, it also marks a spot where an increasingly busy social path dropped down to Middle Oneonta Falls. The growing traffic to this off-trail falls was already taking its toll on the terrain before the slide. So, was the landslide triggered by erosion along the social path? There’s no way to know, but it’s certainly possible that the social path contributed to the sudden instability of the slope.

On my last visit to the upper Oneonta Canyon before the 2017 fire, I ran into bit of trail legend named Bruce, who was a longtime trail worker in the Gorge dating back to the 1980s. He was rebuilding the approach to the slide, and we talked about how Forest Service crews were struggling to simply keep pace with the impact of growing crowds and shrinking agency staff for basic trail maintenance. Major repairs, like those required the slide, were completely overwhelming his crews.

Bruce was wistful about the situation, as he was planning to retire soon, and the trails he had worked so hard on were not faring well as he prepared to turn them over to a new generation of trail workers.

Beyond the problematic landslide, the Oneonta Trail arrives at Triple Falls, an iconic destination that most hikers are coming here for. In the years before the fire, the overlook at Triple Falls was literally crumbling under the pressure from overuse. The photo below shows the view from the main trail, where a tangle of social paths cutting directly downslope to the badly eroded viewpoint can plainly be seen.

A well-graded spur trail provides access to the viewpoint, but few used it. Instead, most follow the steps of this hiker (below) and simply cut directly up the slope to rejoin the trail. Over the past decade, the damage from erosion here had increased alarmingly.

Earlier this year, the volunteer trail crews assessing the Oneonta Trail captured these views of the Triple Falls overlook, showing how the burned over landscape also offers a unique opportunity to rethink and rebuild this overlook trail before hikers are allowed to return.

Just beyond Triple Falls, the Oneonta Trail crossed the creek on this upper footbridge (below), installed by volunteers and Forest Service crews about ten years ago.

This year’s volunteer crews found that the 2017 fire hadn’t spared the upper bridge, as the photo below shows. This represents yet another opportunity to think about how the area will reopened. While the bridge provides critical link to the rest of the Oneonta Creek trail system, it also led to a growing network of eroding social paths on the east side of Triple Falls.

Today, we have a unique opportunity for a reboot, with the canyon just beginning its post-fire recover and still closed to the public. As traumatic as the Eagle Creek Fire was for those who love the Gorge, having the forest burned away was like lifting a window shade on the terrain beneath the forest. Where the fire destroyed a dense forest, it also laid bare the underlying terrain and geology, providing a rare opportunity to plan for our Gorge trail system as it enters its second century.

For trail builders, it’s a perfect opportunity to take a good look at the land for opportunities to refine existing trails and to build trails for future generations of hikers. This includes adjusting existing trail alignments to more stable terrain and replacing social paths with sustainable trails that can help curious hikers explore the beauty of the area without harming it. The fire also cleared the forest understory, making trail building a lot easier.

A New Vision for Oneonta

With this unique opportunity in mind, this proposal focuses on a new loop trail along the middle section of Oneonta Canyon, where little known Middle Oneonta Falls has been hidden in plain sight over the century since the first trail was built here. Middle Oneonta Falls is among of the most graceful in the Columbia Gorge, and waterfall enthusiasts have long followed the steep, brushy social path that led to the falls. I made my first trip there in the late 1970s, when I was 16 years old, and returned many times over the years.

It’s hard to know why the original trail builders passed by Middle Oneonta Falls, and chose to route the main trail high above the falls. The falls can plainly be heard thundering in the forest below, and from one spot on the trail, the brink of the falls can be seen. But for most hikers, Middle Oneonta Falls remained unknown.

This proposal would change that, with a new loop that would not only lead hikers to Middle Oneonta Falls on a well-designed trail, but also take them behindthe falls! More on that, in a moment. Here’s the general location of the proposed loop (shown in yellow) as it relates to the existing Oneonta and Horsetail Creek trails (shown in green):

[click here for a large map]

Why build a new loop trail at Middle Oneonta Falls? One reason is pragmatic: the word is out, and this beautiful waterfall is no longer a secret, as well-worn social paths prove. And, with the forest now burned away, the falls will be plainly visible from the main Oneonta trail, making it impossible to prevent new social paths from forming as curious hikers look for a way to reach the falls.

Given these realities, this concept also focuses on how to make a new loop trail to Middle Oneonta Falls one that provides a new and much-needed destination for casual hikers and families with young kids looking for something less strenuous than what a lot of Gorge hikes require. Loops are the most popular trail option for hikers, too, since they provide a continuous stream of new scenery and adventure.

In the long-term, loops also offer a management tool that is seldom used today, but has great merit in heavily traveled places like the Gorge: one-way trails. On crowded trails in steep terrain, one of the biggest impacts comes from people simply passing other hikers coming from the option direction, gradually breaking down the shoulders of trails over time. One-way trails eliminate this problem, and the provide a better hiking experience with less sense of crowding, too.

With these trail themes in mind, what follows is a tour of the proposed Oneonta Loop Trail, using an exceptional series of aerial photos captured by the State of Oregon in the aftermath of the Eagle Creek Fire.

The first view (below) captures the existing Oneonta Canyon trail system from Oneonta Falls to Triple Falls, with the proposed new loop trail shown in yellow. The new loop trail would follow the more stable east side of Oneonta Canyon, avoiding the landslide on the west side (which is also shown on the map).

[click here for a large map]

As the above map shows, another benefit of the proposed loop is that it could also serve as a reroute for the existing Oneonta Creek Trail if it becomes impossible to maintain a trail across the landslide, as the new loop would connect to the main trail upstream from the slide.

The next series of maps walk through the proposed loop trail in more detail, starting at the bottom, where the new trail would begin where a social path already extends into the canyon from the lower Oneonta Bridge (below).

[click here for a large map]

From there, the route to Middle Oneonta Falls is surprisingly straightforward (below), and quite short — less than one-half mile. This would make the falls an easy destination for young families and hikers who don’t want to tackle the longer and more strenuous climb to Triple Falls.

[click here for a large map]

Once at Middle Oneonta Falls (below), the new trail would take advantage of the huge cavern behind the falls to avoid building and maintaining another trail bridge, and simply pass behind the falls, instead.

[click here for a large map]

For hikers coming from the Horsetail Falls trailhead, this would also be the second behind-the-falls experience, having already passed behind Ponytail Falls along the way. This would make the hike to Middle Oneonta Falls a magnet for families with kids, as nothing quite compares with being in a cave behind a waterfall for young hikers!

After passing behind Middle Oneonta Falls, the new loop trail (below) would climb the west slope of Oneonta Canyon just upstream from the slide in a series of four switchbacks, and rejoin the main trail. From there, hikers could continue on to Triple Falls or turn back to the trailhead to complete the new loop.

[click here for a large map]

The next few schematics show how the trail would pass behind beautiful Middle Oneonta Falls. The first view (below) is from slightly downstream, and shows the forested bench opposite the falls where the new trail would descend toward the cave.

[click here for a large schematic]

The next view (below) is from the base of the cliffs at the west side of the falls. The big boulder shown in the previous schematic should help you orient this view, as it is marked in both schematics. This view provides a better look into the cave, which is made up of loose river cobbles and well above the stream level in all but the heaviest runoff. Note my fellow waterfall explorer behind the 90-foot falls (!) for scale.

[click here for a large schematic]

A third schematic of the falls (below) is from further downstream. This view gives a better sense of the large bench in front of the falls where the approach trail would be located, and how the exit from the cave would navigate a narrow spot between the creek (by the “Big Boulder”) and cliffs on the west side of the falls.

[click here for a large schematic]

As the photos in these schematics show, this is an exceptionally beautiful spot, and though it is now recovering from the fire, it would still make for an easy and popular new destination in the Gorge. Would more visitors make it less pristine? Perhaps, but on my last trips to Middle Oneonta Falls I had to clean up campfire rings built directly adjacent to the creek and carry out beer cans and trash, so it’s also true that legitimizing the trail here would bring “eyes on the forest that would help discourage this sort of thoughtless damage.

Further upstream, there’s also work to do at Triple Falls. This map (below) shows how the main trail could be relocated to follow the existing (and seldom used) spur to the viewpoint and be extended to simply bypass the section of existing trail that drives creation of social trails.

[click here for a large map]

This would provide a long-term solution to the maze of social paths that have formed between the existing trail and the Triple Falls viewpoint. This is a very simple fix, and should be done immediately, while the area is still closed to hikers and the burned over ground and exposed rock make trail construction much easier.

What would it take?

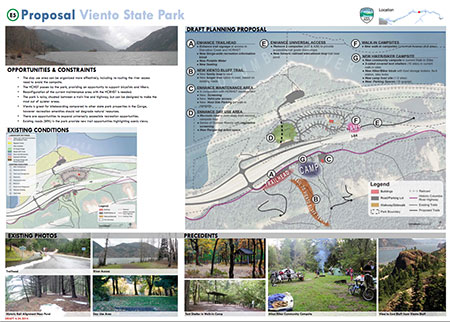

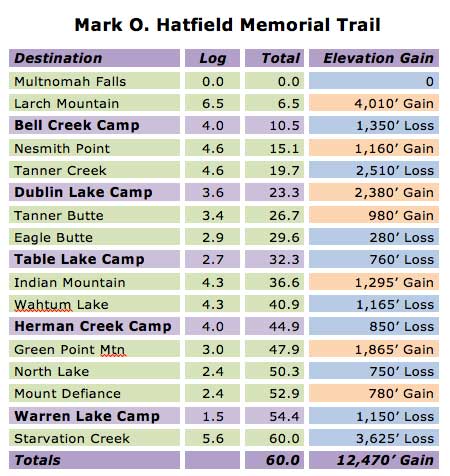

The entirety of Oneonta Canyon is within the Mount Hood National Forest, but administered by the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area (CRGNSA) unit of the Forest Service. Despite the creation of the scenic area in 1986 as a celebration of the beauty of the Gorge, there have been no new trails on Forest Service lands in the western Gorge for more than three decades. In fact, the agency has periodically proposed abandoning some of the lightly used backcountry trails in the Mark O. Hatfield Wilderness that have fallen behind in maintenance.

The Forest Service is reacting to a long period of strained recreation budgets dating back to the 1990s, but our recent history of disinvestment should not prevent us from looking ahead to the needs of this century. The lack of a future vision is part of what prevents new trails from being designed and built, as there are already plenty of ideas for new trails that could be sustainably built in the western Gorge to help take pressure off the existing system.

The last new trail built in this part of the Columbia River Gorge is the Wahclella Falls loop, completed in 1988. Today, this wonderful loop trail is iconic and among the most beloved in the Gorge. But until the 1980s, a brushy, sketchy user path is how hikers reached Wahclella Falls. Recognizing the need to formalize an official trail, the Forest Service worked with volunteers who completely rebuilt the old trail and added a new leg on the west side of the canyon, creating the well-designed, exceptional loop we know today.

Tiny Maidenhair spleenwort (for scale, the larger fronds at the top of Licorice fern!) are as uncommon as they are beautiful, and are found along the Oneonta Creek Trail near Triple Falls

This proposal for an Oneonta Loop trail would be a great candidate for a similar effort, with Forest Service and volunteer workers creating a new trail that would not only provide a much-needed trail option in the western Gorge, but that would also remedy the social trails that have developed and potentially serve as a new, main route if the landslide on the current trail cannot be stabilized.

In the aftermath of the Eagle Creek Fire, now is a perfect time to reboot trail building in the Gorge and Oneonta would be the perfect spot to get started. The area is still closed to the public, and trail volunteers have already begin scouting the trail to assess fire damage and make plans for repairs. This scouting work could be expanded to site the new loop trail, and there’s no better way to bring volunteers to trail projects than to build new trails.

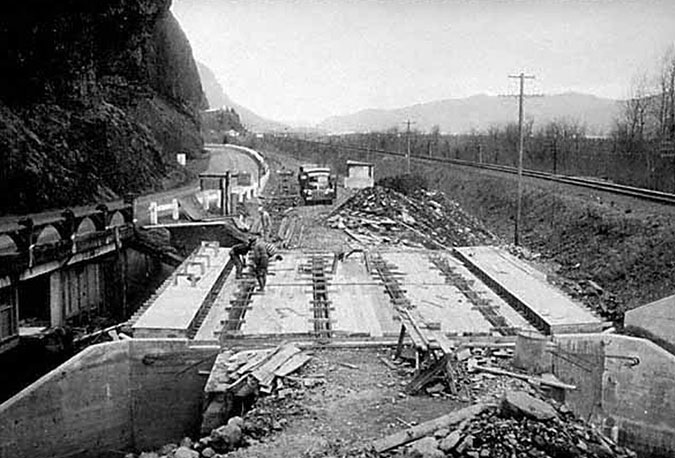

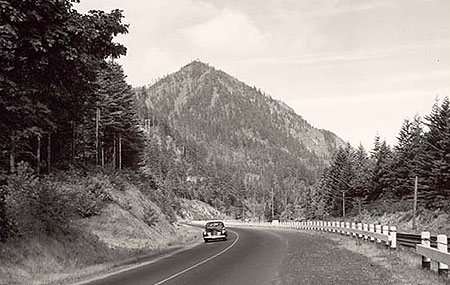

And finally, consider this: almost all of the trails in the Columbia Gorge (and the rest of Mount Hood National Forest) were built over the course of just two decades, in the 1920s and 30s. Amazingly, the system we have today is less than half of what was existed before the industrial logging era began after World War II. And in that period of decline, few new trails were added.

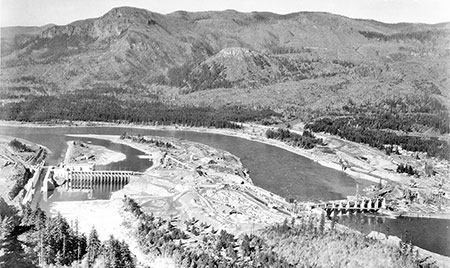

While forest trails were initially built as basic transportation for forest rangers, the Great Depression brought a new focus on recreation and enhancing our public lands through the work of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCA) and Works Progress Administration (WPA). Our best trails were built during this golden age of trail construction, when trails were designed to thrill hikers with amazing views and adventures. These federal workforce program were put in place under Franklin D. Roosevelt as part of the national recovery plan, when unemployment during the Great Depression exceeded 20 percent, with no end in sight.

Sound familiar? Our normally gridlocked U.S. Congress has just allocated nearly $4 trillion in emergency funding to shore up the country as an unprecedented Coronavirus pandemic takes hold. And congressional leaders are already proposing more stimulus funding in the form of public infrastructure to continue pumping money into the economy and creating work for the jobless. Are we on the brink of another trail-building renaissance in our national forests? Quite possibly — but only if we begin planning for that possibility now.

___________________

And one more thing…

There is a LOT of confusion about place names on Oneonta Creek. USGS topographic maps show only Oneonta Falls and Triple Falls, but Oneonta Falls is shown where Middle Oneonta Falls is located. This is clearly a map error, though one that has endured (and confused) for a very long time. In fact, Oneonta Falls is the tall, narrow falls at the head of Oneonta Gorge and is identified as such in early photos of the Gorge taken long before anyone knew much about the upper canyon.

Meanwhile, there’s a small waterfall right in front of the lower Oneonta footbridge that is often called “Middle Oneonta Falls”, only because it’s in plain sight and so few know that there’s a much larger “Middle Oneonta Falls” just a half-mile upstream. Fortunately, the USGS got Triple Falls right!

So, for the purpose of this article (and in general), I refer to the small falls by the lower footbridge as “Oneonta Bridge Falls”, just to clear things up a bit. Creative, right? Well, neither is “Triple Falls”! Or “Middle Oneonta Falls”, for that matter! But at least we know which waterfalls we’re talking about. Remember, there’s no detail too small for THIS blog!

Thanks again for reading this far, folks!

___________________

Tom Kloster | May 2020