Mirror Lake and Mount Hood from Tom Dick and Harry Mountain

Big changes are coming to the Mirror Lake Trail on Mount Hood, perhaps the single most visited trail on the mountain. This is the third in a three-part series on the future of Mirror Lake, and the need for a broader vision to guide recreation in the area. This article focuses on a (much!) bolder vision that would provide new backcountry experiences and help take pressure off heavily visited Mirror Lake.

_____________

On March 30, 2009, President Obama signed into law a wilderness bill that brought thousands of acres of land around Mount Hood under permanent protection from logging and other commercial development.

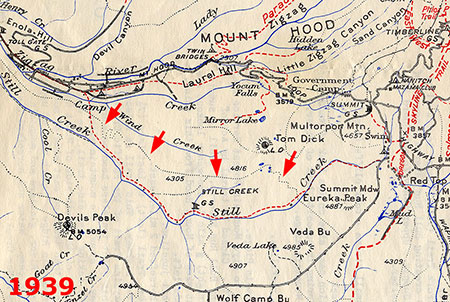

Most of these new areas were expansions of existing wilderness, and such was the case for the backcountry that forms the backdrop for Mirror Lake. This new wilderness area stands as an island, bounded by US 26 on the north and the Still Creek Road on the south. This map shows the new island of wilderness:

Click here for a larger map

The new wilderness area encompasses most of the remote, seldom visited Wind Creek drainage and much of Tom Dick and Harry Mountain. As you can see from the map, this island wilderness was added to the nearby Salmon-Huckleberry Wilderness, located to the south. That might be because the new area falls below the 5,000 acre threshold for new wilderness, but it was a missed opportunity to give the area its own wilderness identity.

While Mirror Lake, itself, was left just outside the boundary, the rugged mountain backdrop above the lake is now protected in perpetuity from development, and ski resort expansion, in particular — and whatever else might have been dreamed up by those trying to exploit this beautiful area to make a buck off our public lands.

The rugged slopes of Tom Dick and Harry Mountain rising above Mirror Lake are now protected forever

The new wilderness protection also offers an opportunity to rethink how Mirror Lake itself will be protected in the long term. While not the closest wilderness area to the Portland region, it is perhaps the most accessible. That means demand for exploring the Mirror Lake area will only grow over time, no matter where the new trailhead is eventually located.

The Mirror Lake trailhead study took a baby step toward a broader vision for the wilderness area with the intriguing (and now discarded) “Site 5”, which would have moved the trailhead to the base of Laurel Hill, along Camp Creek (see below). Forest Service planners considered a new trail along Camp Creek to connect this lower trailhead to the existing trail – and in doing so, briefly floated the idea of a completely new streamside hike, something the Mount Hood area is woefully short on.

Click here for a larger map

It’s true this site would have been a poor replacement for the existing trailhead, simply because of its distance from Mirror Lake. But the idea should be still explored on its own merits – along with other opportunities to build a true trail network in the new Mirror Lake wilderness.

While the Forest Service is rightly concerned about the impacts of heavy foot traffic on Mirror Lake, making it more difficult to get there doesn’t solve the larger issue: over the next 25 years, a million new residents are expected in the greater Portland region, and new trails are essential to spreading out the already overwhelming demand from hikers.

Mount Hood from Tom Dick and Harry Mountain

But you might be surprised to know there are no plans to do so. For a variety of frustrating reasons, the Forest Service is doing just the opposite: hundreds of miles of trails are suffering from serious maintenance backlogs, and the agency is actively looking for trails to drop from the maintained network across the Pacific Northwest.

At Mount Hood, the Forest Service is still working from a decades-old forest plan that was written when the Portland region was smaller by about 800,000 residents. In that time, you can count new trails added to the system on one hand – while dozens of legacy trails have been dropped from maintenance. We hear that there’s no just money for trails – and yet, millions are spent each year on the other programs that are clearly a greater Forest Service priority.

To reverse this counter-intuitive downward spiral, the first step is a bold vision to shift the agency toward embracing new trails, and moving recreation to the top of their priorities for Mount Hood. The Mirror Lake area is a perfect place to start.

Taking the Long View

New trail proposals are a regular feature in this blog, but they are usually very specific fixes to a particular trail that should happen in the near term (with a couple of notable exceptions focused on backcountry cycling, found here and here.

The following proposal is different: this is a trail concept that would likely be built over years and decades, but with an eye toward a complete system over the long term. The goal is to absorb some of the inevitable growth in demand for trails while also offering a reasonable wilderness experience.

The proposal comes in two parts. The first focuses on Mirror Lake and the adjacent island of wilderness that encompasses the Wind Creek Basin, while the second part focuses on connections to the main Salmon-Huckleberry Wilderness, to the south. The trail concepts for the first part are shown on this map:

Click here for a larger map

The trails shown in red on the map are new trail proposals, and would be built over time to provide alternatives to the overused Mirror Lake trail. Trails in green exist today. The new trails would provide access to new, largely unknown scenic destinations in this pocket wilderness, as well as overnight wilderness camping potential for weekend backpackers.

A key piece in this trail concept is a pair of new routes that would create a Mirror Lake loop from the proposed trailhead at Ski Bowl (see close-up map, below).

Click here for a larger map

While the other trail concepts proposed in this article are intended as a long-term, alternative vision to the status quo in the Mirror Lake area, the Mirror Lake loop trails could – and should — happen in the near term. The Mirror Lake loop concept builds on existing trails and could be built today, if the Forest Service were to embrace the idea.

The new connecting trail from the proposed Ski Bowl trailhead is already part of the Forest Service proposal for relocating the existing trailhead, and will be constructed as part of moving the trailhead.

The Tom Dick and Harry traverse concept (the 1.3 mile connector along the north slope of the mountain) could be an important complement to the existing up-and-back trail by offering a loop option. The connector would also provide a real trail alternative to the informal summit ridge trail that eventually ends up following service roads under ski lifts back to the trailhead.

Loop trails not only reduce the impact on individual routes, they also offer more scenery for hikers and less crowding – which helps ensure a better wilderness experience.

Moving to the north edge of the Mirror Lake trail concept map, the “Site 5” idea of a lower trailhead along Camp Creek is included, connecting from the Site 5 trailhead location to the Mirror Lake Trail.

While this trail concept seems to be too close to the US 26 highway corridor to provide much of a respite from urban noise, the saving grace is Camp Creek, itself. The creek tumbles along several hundred feet below the, and the sounds of this mountain stream would be more than enough to mask highway noise for hikers if the trail were designed to follow the creek.

Looking down… waay down at Camp Creek from Highway 26

The Camp Creek trail concept has a lot to offer hikers: a rare, streamside trail in the Mount Hood corridor, an easy grade for families and a year-round hiking season, with most of the proposed trail located below the winter snow level.

Best of all, the Camp Creek canyon hides a once-famous series of cascades that make up Yocum Falls. These falls are seldom visited today, but the Camp Creek trail concept would pass in front of the beautiful lower tier of this series of waterfalls before climbing to the Mirror Lake trail. The falls would likely become the main focus of this trail for families or casual hikers looking for a short 3-mile, streamside hike.

Beautiful Yocum Falls on Camp Creek

Building on the “Site 5” trailhead and Camp Creek trail proposal, this Mirror Lake trails concept includes a new route that would explore Wind Creek. This route would begin at Site 5, following Camp Creek downstream to Wind Creek, then climb into the remote Wind Creek basin. This proposed trail would provide a true wilderness experience, just off the Highway 26 corridor.

Along the way, the proposed Wind Creek trail would include a short spur (see map) to an overlook atop the familiar, towering cliffs that are prominently seen from Highway 26 along the north slope of Tom Dick and Harry Mountain.

Google Earth view of the familiar cliffs on Tom Dick and Harry Mountain that would provide a short viewpoint destination off the proposed Wind Creek Trail.

Mount Hood as it would appear from the new viewpoint along the proposed Wind Creek Trail.

But the Wind Creek trail concept would have even more to offer hikers: waterfall explorers Tim Burke and Melinda Muckenthaler recently discovered a series of beautiful, unmapped wateralls along Wind Creek where it tumbles from its hanging valley into Camp Creek.

Middle Wind Creek Falls (photo courtesy Tim Burke)

Upper Wind Creek Falls (photo courtesy Tim Burke)

Above the waterfalls, the proposed trail would enter the Wind Creek Basin, eventually connecting with existing trails on Tom Dick and Harry Mountain to create a number of possible loop hikes and backpacking opportunities.

Foremost among the backpack destinations would be Wind Lake, a pretty, surprisingly secluded lake that is currently only accessible by first navigating a tangle of service roads and resort trails at Ski Bowl. The Wind Creek trail concept would allow hikers to visit this wilderness spot without having to walk through the often carnival-like activities that dominate during the summer months at the resort.

Wind Lake (Photo courtesy Cheryl Hill)

A final piece of the concept for the Mirror Lake-Wind Creek backcountry would be a new trail connecting Wind Lake to the Still Creek Road and Eureka Peak Trail. This new route would pass a couple of small, unnamed lakes south of Wind Lake, then traverse a rugged, unnamed overlook that towers 1,600 above the floor of the Still Creek valley (see concept map, above).

Looking across the seldom-visited Wind Lakes Basin toward Mount Jefferson

The proposed trail linking Wind Lake to the Eureke Peak trail would also be the first step in better connecting the wilderness island that encompasses the Wind Creek Basin and Mirror Lake to the main Salmon Huckleberry Wilderness, to the south. And on that point…

Thinking even bigger!

In the long-term, the island of wilderness that covers the Wind Creek-Mirror Lake area should be more fully integrated with the main Salmon-Huckleberry wilderness to enhance both recreation and the ecosystem. This second part of the trail concept for the Mirror Lake area is a broader proposal that encompasses the north edge of the main Salmon-Huckleberry wilderness area, and includes few ideas on how to get there (see map, below).

Click here for a larger map

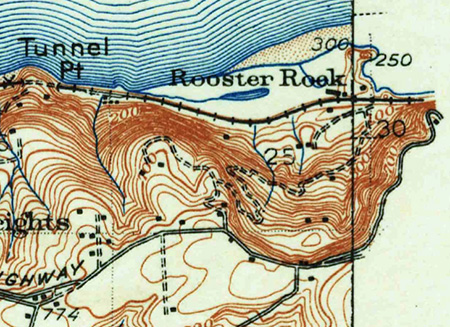

The centerpiece of this part of the trail proposal is to close Still Creek Road from the Cool Creek trailhead to the Eureka Peak trailhed to motorized vehicles. The concept is to leave this nearly 6-mile section of road (shown in yellow on the map) open to cyclists and horses and for occasional administrative use by Forest Service vehicles.

Beautiful Still Creek

A corresponding trail concept (shown on the above map) is to build a stream-level hiking trail that parallels the service road, but alternates at each bridge, staying on the opposite side of Still Creek from the road. True, hikers could simply follow the closed road, but the idea is to offer another much-needed, low elevation streamside trail to the area, taking pressure off the few options that currently exist (in particular, the Salmon River).

Closing the trail to motor vehicles would also help control some of the historic problems with dumping, target shooting and vandalism in the area. It would also create a quiet zone for wildlife moving between the main Salmon Huckleberry Wilderness and the wilderness island covering the Mirror Lake-Wind Creek area.

Another concept in this second, broader proposal is a ridge trail along the Salmon River-Still Creek divide, from Devils Peak to Eureka Peak. This little-known arm of the Salmon Huckleberry Wilderness is dotted with rock outcrops and open ridges that offer sweeping views of Mount Hood and the Still Creek valley. This trail concept would new backpack loops possible from the Highway 26 corridor.

The Salmon River-Still Creek Divide (with clouds filling the Still Creek valley)

The ridge trail concept proposes two new trails between Veda Butte and Eureka Peak, creating a smaller loop in this area that would traverse open talus slopes and ridge tops with fine views of Mount Hood and Veda Lake.

Veda Lake and Mount Hood

Veda Lake and Veda Butte

The west end of the proposed ridge trail would connect to the extensive network of trails that converge on Devils Peak and its historic lookout tower. The Cool Creek, Kinzel, Green Canyon and Hunchback Mountain trails would all connect to the proposed ridge trail, creating many hiking loop and backpack options, as well as trail access from the Salmon River area to the Mirror Lake and Wind Creek backcountry.

Mount Hood from the Cool Creek Trail

Is this vision for Mirror Lake and the Wind Creek Basin farfetched? Only if we limit our imagination and expectations to the existing forest management mindset.

Consider that nearly all of the trails ever built on Forest Service lands were constructed in just a 20-year span that ended in the mid-1930s, using mostly hand tools, and with budgets a fraction of what is spent today. The real obstacles to a renewed focus on trails and recreation aren’t agency resources, but rather, a lack of vision and will to make it happen.

What can you do?

Mirror Lake in winter

For now, these trail concepts are just a few ideas of what the future could be. The critical step in the near term is to simply avoid losing ground when the Mirror Lake trailhead is moved. If you haven’t commented already, consider weighing in on the issue – the federal agencies are still accepting our feedback!

Here are three suggested areas to focus on your comments on:

- What would you like to see in the preferred alternative? (see Option 4 in the first part of this article series)?

Are you frustrated with the winter closure of the existing Mirror Lake trailhead? Be sure to mention this in your comments on the proposed new trailhead, as it will need to be design to be plowed and subsequently added to the Snow Park system to serve as a year-round trailhead.

Consider commenting on other trailhead amenities, as well, such as restrooms, secure bicycle parking, trash cans, drinking fountain, signage, picnic tables, a safe pedestrian crossing on Highway 26 for hikers coming from Government Camp or any other feature you’d like to see.

- How would you like to see Camp Creek protected?

The project vaguely proposes to restore the existing shoulder parking area to some sort of natural condition. Consider commenting on how this restoration might work to benefit Camp Creek, which is now heavily affected by highway runoff and the impacts of parking here.

In particular, mention the need to divert highway runoff away from Camp Creek for the entire 1-mile stretch from the old trailhead to the Ski Bowl entrance. The proposed parking area restoration is the perfect opportunity to address the larger need to improve the watershed health.

- Would you like to see a new vision for the larger Mirror Lake/Wind Creek backcountry?

Share some of the ideas and proposals from this article or other ideas of your own! The Forest Service recreation planners are reviewing the comments from the trailhead relocation project, so it can’t hurt to make a pitch for more trails in the future – even if the recent history has been in the opposite direction.

In particular, mention the loop trail idea described for Mirror Lake, particularly the traverse trail shown on the first concept map. This new trail has a real chance of being built in the near term of there’s public support for it.

You can comment to Seth Young at the Federal Highway Administration via e-mail or learn more about the project here:

Mirror Lake Trailhead Project Information:

Federal Highway Administration

Seth English-Young, Environmental Specialist

Western Federal Lands Highway Division

610 East Fifth Street

Vancouver, WA 98661-3801

Phone: 360-619-7803

Email: seth.english-young@dot.gov

Subscribe to Project Newsletters

To be added to their mailing list, please send an email to seth.english-young@dot.gov.

For U.S. Forest Service specific questions contact:

Laura Pramuk

Phone: 503-668-1791

Email: lbpramuk@fs.fed.us