White River Falls during spring runoff

Every year, a growing number of summer visitors flock to White River Falls State Park to witness the spectacle pictured above, only to find a naked basalt cliff where the falls should be! The spring runoff has long since subsided by mid-summer, and field irrigation in Tygh Valley also draws heavily from the tributary streams that feed the river during the dry season. Worse, part of what’s left when this federally protected Wild and Scenic River finally reaches the park is diverted by a century-old waterworks into a side channel that bypasses the main falls. It’s a sad sight compared to the powerful show in winter and spring, but it doesn’t have to be this way.

Many of these same visitors hike down to see the historic, century-old powerhouse at the base of the falls that once used the diverted river water to spin some of Oregon’s earliest hydroelectric turbines. Though mostly in ruins, the site is fascinating – yet the trail to it is a slick, sketchy goat path coming apart at the seams that hikers struggle with. This short hike doesn’t have to be this way.

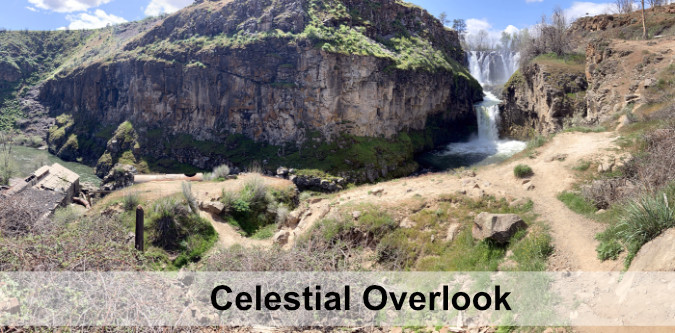

The hidden lower tier and punchbowl is called Celestial Falls

Lower White River Canyon

Some hikers push beyond the historic powerhouse to the lesser-known lower falls, and then still further, to a dramatic view into the lower White River canyon. Here, the river finally has carved a rugged path to its confluence with the mighty Deschutes, just a few miles downstream. It’s a striking and beautiful riverside hike, but the “trail” consists of a maze of user paths that are gradually destroying the drifts of wildflowers along the canyon floor. This trail doesn’t have to be this way, either.

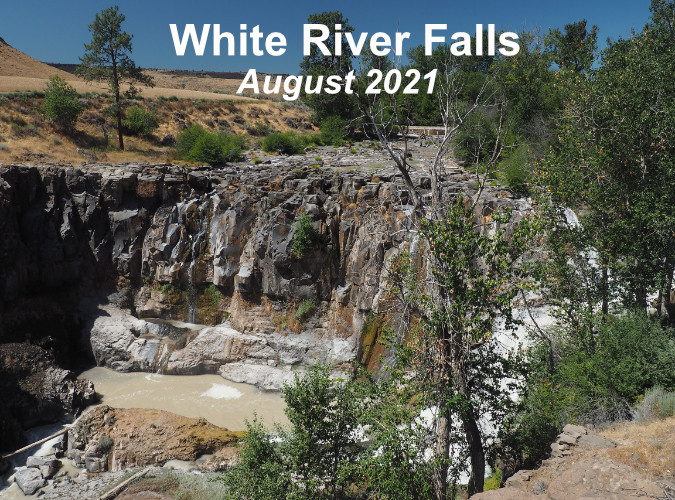

Lesser-known Lower White River Falls

In recent years, White River Falls State Park has also become a popular stop for cyclists touring the route from Maupin to Tygh Valley, then looping back through the Deschutes River canyon. While the park has an excellent restroom and day-use picnic area that would make for a terrific stopover, overnight camping is not allowed, even for cyclists camping in tents. This, too, does not have to be this way.

The increased popularity has begun to noticeably wear on the park. The good news is that in the past couple years Oregon Parks and Recreation (OPRD) rangers and the park’s dedicated volunteer park hosts have stepped up their efforts to care for the park infrastructure and get a handle on vandalism (mostly tagging) that had plagued the historic powerhouse. Still, much more is needed to unlock the amazing potential this park holds as a premier destination. It’s time to reimagine White River Falls.

Historic White River Powerhouse just downstream from the falls

[click here for a larger view]

Turbines inside the powerhouse a few years ago, before vandalism began to take a heavy toll. Oregon State Parks has since closed off entry with heavy barriers

[click here for a larger view]

As it stands, the park lacks a comprehensive vision for how its natural and historic wonders can best be protected, while still keeping pace with ever-growing numbers of visitors. It’s a surprisingly big and mostly undiscovered place, and an updated blueprint could achieve both outcomes: protecting and restoring the natural and historic landscape for future generations, while also making it accessible for all to explore and enjoy. While the park includes a surprising amount of backcountry now, White River Falls also holds the potential to become a much larger park that restores and showcases the unique desert landscape and ecosystem found here.

This article includes several proposals for new trails and campsites to better manage the growing demand and provide a better experience for visitors, expanding the park to better protect the existing resources, and even a re-plumbing of the waterworks to allow White River Falls to flow in summer as it once did before it was diverted more than a century ago.

An Unexpected Past

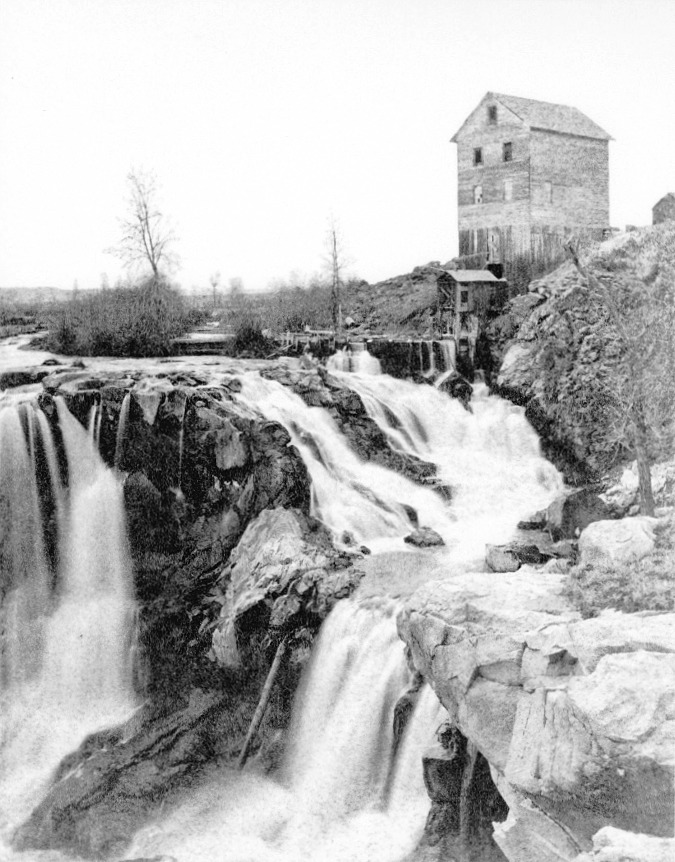

Grist mill at White River Falls in the late 1800s. This rare view reveals a northern cascading segment of the falls to have been part of the natural scene, and not created by the power plant diversion channel that was constructed in the early 1900s.

White River Falls was never envisioned as a park by the white migrants who settled in Tygh Valley and Wasco County in the mid-1800s. In their day, waterfalls were viewed mostly as obstacles to river navigation or power sources to run mills. The falls surely had a more spiritual and harmonious value to native peoples who had lived, fished and gathered along its banks for millennia before white settlers arrived. The Oregon Trail passed through Tygh Valley, and soon the new migrants had cleared the valley and began to build irrigation ditches to bring water to the cleared farmland. By the late 1800s, a grist mill was built at White River Falls, powered by the falling water.

By the early 1900s, the grist mill was replaced with a much more ambitious project, and the abandoned hydroelectric plant we see today was constructed at the base of the falls in 1910. A concrete diversion channel was built where the grist mill stood, and a low diversion dam brought a steady flow from the White River into a series of pipes and penstocks that powered the turbines below. Power from the new plant was carried north to The Dalles, one of the earliest long-distance hydroelectric transmission projects in the country.

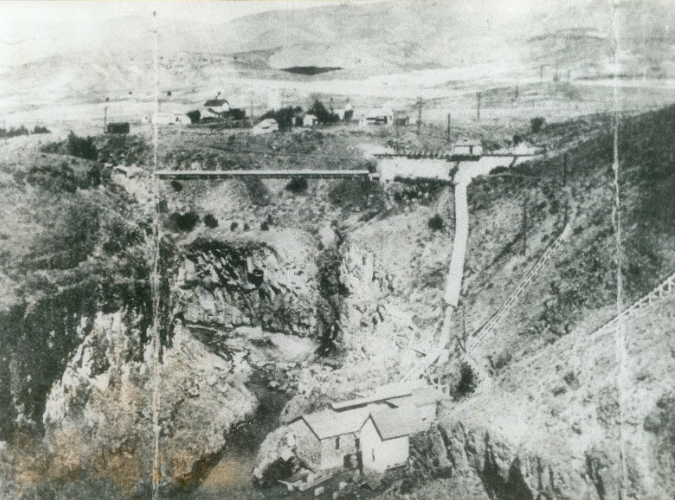

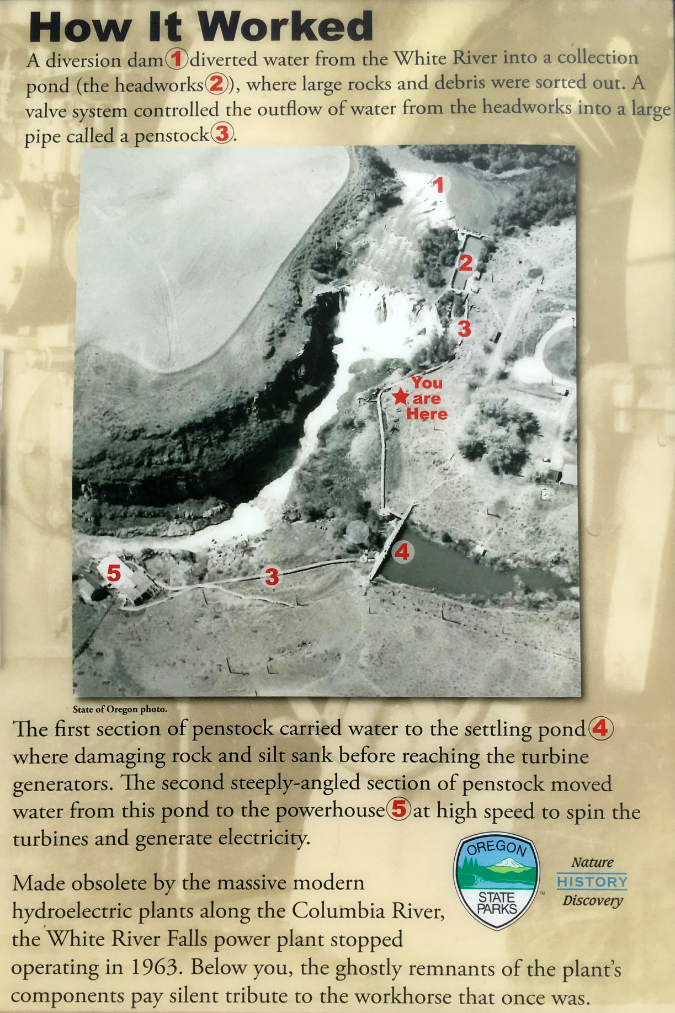

Aerial view of the White River Powerhouse and network of penstocks taken in the early 1900s. The group of structures at the top of the photo were located where today’s picnic area and restrooms are now. This photo also shows the concrete dam holding the settling pond, in the upper right. This structure still exists today. The diversion dam is partly visible at the left edge of the photo, with its diversion pipe leading first to the settling pond, then to the lower penstock pipe leading down to the powerhouse at the bottom of this photo.

The White River is a glacial stream that flows from a glacier by the same name on Mount Hood’s south slope, just above Timberline Lodge. Because of its glacial origin, the hydro plant included a large settling pond to separate the fine, grey glacial till that gives the White River its name. The settling pond still survives today (albeit dry), along with the diversion dam and much of the pipe and penstock system. These features are all visible in the aerial photo (above) and described in the interpretive schematic (below) provided by Oregon State Parks.

[click here for a larger view]

After fifty years of operation, the powerhouse had become obsolete and fallen into disrepair, and by the early 1960s it was abandoned. Giant new dams on the Columbia and Deschutes rivers had long since eclipsed it, and the constant chore of separating glacial sediments from the river water made it costly to operate.

How white is the White River? This recent aerial view shows the White River flowing from the upper left corner toward its confluence with the Deschutes River, the wide, dark stream flowing from the lower left. When the crystal clear waters of the Deschutes mix with the silty glacial water of the White River during peak glacier melt in late summer, the result is a pale blue-green Deschutes River downstream from the confluence (flowing toward the middle right)

The site was an unlikely candidate for a new park, given the dilapidated buildings and pipelines scattered across the area. But thankfully, the raw power and beauty of White River Falls made the case for a second act as a public park and nature preserve borne from an industrial site. For many years, the reimagined White River Falls was simply the quiet “Tygh Valley Wayside”, and was way off the radar of most Oregonians. It only drew a few visitors and only the gravel parking area and main falls overlook were improved to a park standard.

Panoramic view of Lower White River Falls during spring high water. The basalt bench to the left marks where flood events on the river have repeatedly overtopped this ledge, scouring the bedrock

The park had one (hopefully) final scare in its natural recovery just over a decade ago, when Wasco County pitched a new hydroelectric plant at the site, promising “minimal impact” on the natural setting. Thankfully, Oregon State Parks expressed major concerns and the proposal died a quiet death. You can read an earlier blog article on this ill-conceived proposal here.

Over the past two decades, growth in the Wasco County and increased interest from Oregon’s west side population in the unique desert country east of Mount Hood has finally put White River Falls on the recreation map. Today, the parking area overflows with visitors on spring and summer weekends, and the park has become a deservedly well-known destination. The rugged beauty of the area, combined with the fascinating ruins from another era make it one of Oregon’s most unique spots. These are the elements that define the park, and must also be at the center of a future vision for this special place.

A new vision for the next century: White River Falls 3.0

- New & Sustainable Trails

Weekend visitors skittering down the steep, slick path to the old powerhouse

The trail into the canyon as it exists today is deceptive, to say the least. It beings as a wide, paved path that crosses an equally wide plank bridge below the old sediment pond dam. Once across, however, it quickly devolves. Visitors are presented with a couple of reasonable-looking dead-ends that go nowhere (I will revisit one of those stubs in a moment), while a much more perilous option is the “official” trail, plunging down a slippery-in-all-seasons (loose scrabble in summer, mud in winter) goat path. Still, the attraction of the river below — and especially the fascinating powerhouse ruins – beckon, so most soldier on.

Soon, this sketchy trail reaches a somehow steeper set of deteriorating steps, built long ago with railroad ties and concrete pads. And still, the river continues to beckon, so most folks continue the dubious descent. The “official” trail then ends abruptly at the old powerhouse, where a popular beach along the river is a favorite wading spot in summer. This is the turnaround spot for most visitors. The return up the steps and scrabble of the goat path is challenging in any season, but it’s particularly daunting in summer, when desert heat reflecting off this south-facing wall of the canyon is blazing hot.

Hikers navigating the steep, deteriorating stairway section of the “official” goat path into White River canyon

Looking back at the loose cobbles and scrabble that make up the upper section of the “official” trail into the canyon. Two hikers at the top of the trail consider their fate before continuing the descent

The stairway section has deteriorated enough that hikers are simply bypassing it, which is damaging the slope and causing the stairs to come apart still faster

The railroad tie steps were filled with poured concrete pads at some point, making this a very difficult repair job. In the long term, this section of the “official” trail simply needs to be bypassed with a properly graded route and the old goat path turned back to sagebrush

Beyond the “official” trail, a user path skirts a fenced river gauge, then slips through a patch of waist-deep sagebrush before dropping down to a beautiful streamside flat. Here, Ponderosa pine survive in the deep sand along the riverbank and rugged basalt cliffs soar above the trail. This path soon passes Lower White River Falls before ending at an impressive viewpoint looking downstream, where the White River tumbles another two miles through a deep canyon to its confluence with the Deschutes River.

The “unofficial” trail below the powerhouse was little known just ten years ago, but today it is quickly devolving into a tangle of user paths as an increasing number of visitors push further into the canyon. The flat canyon floor is quickly becoming a maze of these social paths, greatly impacting the desert wildflowers that grow here.

In contrast to the “official” trail, the lower “unofficial” trail rambles at a pleasant grade along various user paths through a beautiful canyon floor framed by towering basalt cliffs

After flying under the radar, the lower canyon has been “discovered”, with a maze of new social paths forming in the past few years that are gradually expanding and destroying the wildflowers that grow here

So, how to fix this? The first step is to improve both the “official” and “unofficial” trail sections to something resembling proper trails. The official route is a tall order, and in the long term, it really needs to be retired and replaced with a correctly graded trail that can be safely navigated and doesn’t trigger heart attacks for visitors making their way back out of the canyon. In the near term, however, simply repairing the damaged stairs and adding a few more in a couple of especially steep sections would buy some time until a better trail can be built.

The unofficial, lower trail is a much easier fix. It simply needs a single route with improved tread and modest stone steps in a couple spots, while also retiring the many braided user paths that have formed. The new interest in the lower trail underscores a more significant need, however, and that’s the main focus of this trail proposal: this hike is simply too short to be satisfying for many visitors.

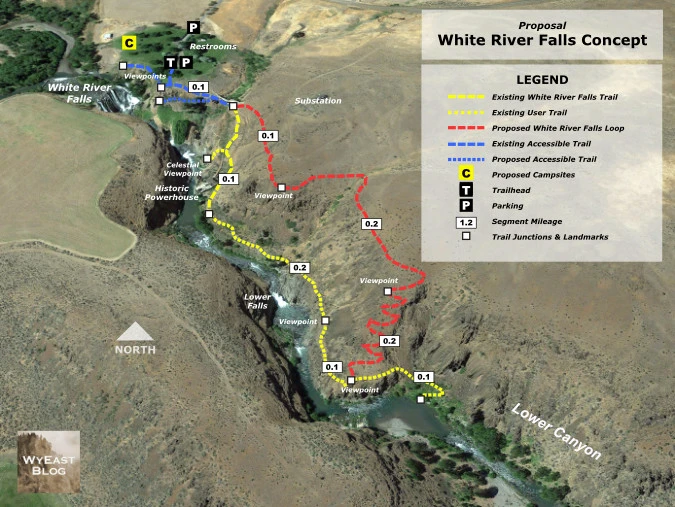

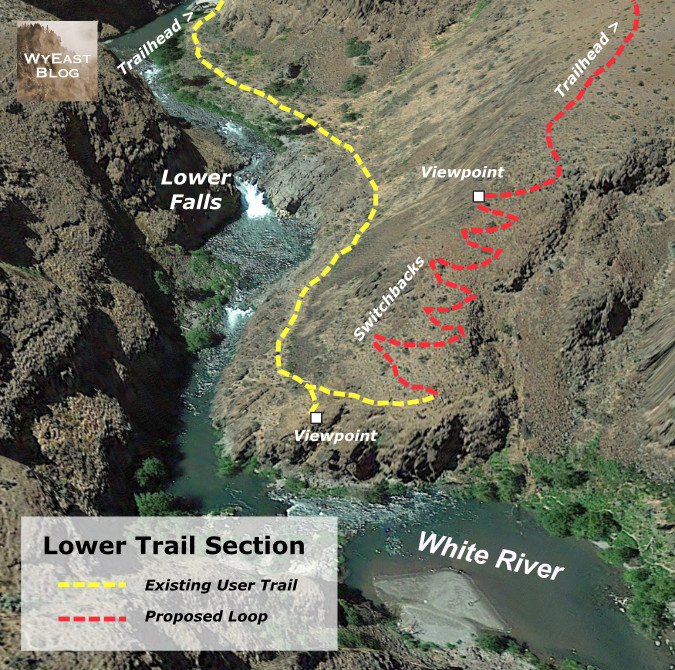

The solution? Build a return loop from the current terminus of the lower, unofficial trail that traverses the canyon rim back to the trailhead. This simple concept is shown in the map, below.

[click here for a larger view]

The proposed return trail (shown in red) would be approximately one-half mile long, making the new loop about one mile in length – short enough for families and casual hikers, yet long enough to make for a more immersive experience. The loop would also allow hikers to avoid climbing back up the goat path section of the existing trail, buying some time until that segment can be rebuilt. The upper end of the proposed loop would actually follow the well-defined game path that many hikers assume to be the main trail where it now connects at the top of the “official” goat path.

Another surprise feature of the loop? The new route would not only provide spectacular views into the canyon and its waterfalls from above, but Mount Hood also appears on the horizon, rising directly above White River Falls. While most hikers would likely continue to first follow the existing trail to the old powerplant, then complete the new loop from there, the rim trail could also work in reverse for hikers looking for big views without the challenging up-and-back climb and steep steps on the existing trail. The upper end of the new rim trail would traverse at a nearly level grade to a spectacular viewpoint (shown on the map, above) that would be a fine turnaround destination just one-quarter mile from the trailhead.

One important detail of this trail concept that should be completed in the near-term is a formalized spur trail to the Celestial Falls overlook. This is an irresistible, yet extremely dangerous overlook just off the main goat path section of the “official trail”, with abrupt, vertical drop-offs and another maze of sketchy social trails.

The stunning overlook at Celestial Falls is a scary mix of ever-expanding social trails and abrupt vertical cliffs that needs near-term attention to be stabilized and made safer for hikers

[click here for a larger view]

Much of the new return trail would follow game paths (like this one at the upper end of the proposed trail) that already traverse above the rim of the canyon.

The new rim trail would bring hikers to this spectacular birds-eye view of White River Falls and Mount Hood on the horizon (Oregon State Parks)

The crux to completing the new loop is a short section of new trail that would climb from the current terminus of the “unofficial” trail to the rim of the canyon, where the new route would then traverse at a nearly even grade back to the trailhead. The crux section follows a sloped ridge through a gap in the canyon rimrock, as is shown in the close-up map (below).

[click here for a larger view]

The end of the user path in the lower canyon marks the start of the proposed new trail, where a set of switchbacks would ascend the slope to the left to the canyon rim and return to the trailhead

The crux section would require some switchbacks and thoughtful trail planning, but it is no steeper than the terrain covered by the “official” trail at the start of the hike. What would it take to make this trail vision happen? More on that toward the end of this article.

2. Accessible Trails

Did you know that rural Oregon has a higher percentage of elderly and mobility limited folks in its population than the state’s major urban areas? Yet, even in our most urban areas, Oregon is woefully short on accessible trails, and the gap is even greater away from major population centers. At White River Falls, there are building blocks for a new accessible trail system that could be phased in over time to become among the finest in the state.

The existing parking area is gravel and would need at least a couple paved spots to be considered accessible

This paved path starts (inexplicably) about 50 feet from the edge of the gravel parking area and leads to the fenced, main viewpoint (in the distance)

Currently, the parking area and initial approach to the main falls overlook is a combination of gravel and mowed lawn that falls short of an accessible. Just a short distance from the gravel parking area, a paved path leads to the fenced overlook of the falls, where interpretive signs tell some of the unique history of the area. It wouldn’t take much to make this viewpoint fully accessible.

The wide plank bridge that crosses below the old settling pond dam (left) and marks the east end of the paved trail system at White River Falls. The “official” goat path down to the old powerplant begins at the far end of the plank bridge

From the main viewpoint, paved routes head off on two directions. The wide, gently sloping main route heads east, across the plank bridge and then ending abruptly where the goat path section of the main trail begins. Like the main viewpoint, this section could be curated to make the terminus at the bridge more interesting as a stopping point, including history of the concrete settlement pond dam that rises directly above the bridge and some of the penstock pipe remains that still survive here. This is also the point where signage marking the hiker trails ahead is sorely needed – including some cautions about the state of the goat path trail.

The west end of paved trail system ends here, at a profile view of the falls

Another paved trail spur heads west from the main viewpoint, along a fenced cliff to a fine profile view of the falls. The pavement ends here, and a user path continues along the fence to a view of the diversion canal that once fed river water into the old hydro plant. This section of the paved trail system is somewhat narrow and uneven, but it could also be improved with some relatively minor work, including improving the surface and creating a more intentional viewpoint of the falls.

From the end of the paving, the fencing continues west to a view of the diversion channel (center)

New interpretive signage could also be added here to tell the story of this part of the park, since this is where the original grist mill also stood. The views here include Tygh Valley, and new signage could also describe the natural history of the White River and the native peoples who lived here before white migrants settled in the area.

Profile view of White River Falls from near the end of the paved section of the west spur. This is a fine viewpoint that could be improved to be a more accessible destination with interpretive stories about the surrounding area

Oregon State Parks has provided picnic tables at the main viewpoint in the past, but to make the existing paved routes more accommodating as accessible trails, several benches along the way would be an important addition. This is perhaps the most overlooked feature on accessible trails, yet they are especially important in a hot desert environment. The National Park Service sets the standard on this front in their parks across the American Southwest, where resting spots are prominent on all trails, especially where a spot of shade is available.

Thinking more boldly, a new accessible trail spur could be added along the nearly level grade below the main viewpoint that once carried water in huge steel pipes. Most of the pipes are gone, but a few remain to tell the story of the old power plant. This grade leads to a front-row view of the main falls that is close enough to catch spray during the spring runoff. It’s also an area where park visitors chronically (but understandably) ignore the many “AREA CLOSED” signs to take in this spectacular view.

Fences and warning signs are no match for these Millennials, but they are right about the view: this lower viewpoint ought to be a spot that more people can enjoy

In this case, the scofflaws are right: this viewpoint ought to be open to the public, and an accessible trail spur would expand that to include all of the public. This proposed accessible spur is shown as the dotted blue line in the trail concept map (above).

Looking east along the existing paved spur to the settling pond dam and plank bridge; the proposed accessible spur trail to the lower falls viewpoint would follow a well-established bench that once held penstock pipe (now covered in blackberries in the lower right)

Another view of the proposed accessible trail spur from the plank bridge, looking west, and showing the blackberry-covered bench that the trail would follow. White River Falls is just beyond the rock outcrop in the upper right

There’s are chunks of penstock pipe along this route, and maybe these could become part of the interpretive history? This entire spur trail concept is possible only because the grade was blasted from basalt for the penstock pipes, which is a great way to connect the industrial history of the site to the park that exists today. From the lower viewpoint, those folks who we rarely provide great accessible trail experiences for would be rewarded with an exhilarating, mist-in-your-face view of White River Falls.

3. Walk-in Campsites

The word is out to cyclists that White River Falls is a perfect lunch spot on touring loops from Maupin and Tygh Valley. The restrooms were recently upgraded, the water fountain restored to include a water supply for filling bottles and there are plenty of shady picnic tables under the grove of Black Locust and Cottonwood trees that surround the parking and picnic areas.

A growing number of these cyclists are “bikepackers” camping along a multi-day tour, often starting from as far away as Portland, and there’s new interest in bike-in campsites for these folks. Unlike a traditional car-camping format, these campgrounds require only a network of trails and simple tent sites with a picnic table.

The modern restrooms at White River Falls State Park have been recently renovated to be accessible and are in top condition

This newly restored water fountain has a handy spigot on the back for filling water bottles (and dog dishes, as seen here)

The park has a nice spot for exactly this kind of campground just to the west of the parking lot and picnic areas. Today, it’s just a very large, mowed lawn that slopes gently toward the White River, with a nice view of Mount Hood. Creating a bike-in campground here wouldn’t take much – no underground utilities or paving would be required, just some paths and graded camp spots. The park already has on-site hosts living here from spring through fall to keep an eye on things, and that coincides with the bicycle touring season.

The wide west lawn adjacent to the main picnic area (marked by the group of trees) at White River Falls State Park

Looking toward the west lawn (and riparian Cottonwood groves, beyond) from the picnic area

Perhaps most important would be to add some trees to shade this area. Right now, the west lawn is blazing hot in summer, so more of the tough, drought-tolerant Black Locusts that grow in the picnic area could provide needed shade without requiring irrigation. Even better, our native Western Juniper would provide some shade, as well as year-round screening and windbreaks.

4. Bringing Back the Falls

From roughly mid-July until the fall rains kick in, a visit to White River Falls can be a bit deflating. Instead of a thundering cascade, the main face of the falls is often reduced to a bare basalt cliff.

White River Falls in full glory during spring runoff

White River Falls by late summer, when most of the flow diverted away from the falls by the old waterworks system

Why is this? In part, seasonal changes in the river from spring runoff to the summer droughts that are typical of Oregon. But the somewhat hidden culprit is the low diversion dam that once directed the White River to the penstocks that fed to the old powerhouse. The hydroelectric plant is now in ruins, but during the dry months the diversion dam still pushes most of the river into a concrete diversion channel, which then spills down the right side of the falls.

The entire flow of the White River was channeled through the diversion channel on this summer day in August 2021. At this time of year, the glacial silt that gives the river its name is most prominent

The entirety of the diversion system is now a relic, and the old dam should be breached. There are more than aesthetics involved, too. White River Falls creates a whole ecosystem in the shady canyon below, with wildflowers and wildlife drawn to this rare spot in the middle of the desert by the cool, falling water.

The earlier image of the original grist mill shows that a side tier of the falls always existed, even before the L-shaped diversion dam was built. However, as this aerial schematic (below) shows, the natural flow of the river is straight over the falls, not over the side tier.

The diversion system at White River Falls is simple. The low, L-shaped dam at the top of this aerial view directs water to the concrete diversion channel at the right. From here, river water once flowed into the metal penstock pipes and on to the hydroelectric works, below. Today, the diversion channel simply flows over a low cataract and back into the main splash pool of White River Falls. In this view, the river was high enough for water to still flow over the diversion dam and then over the falls, but by mid-summer, the dam diverts the entire river into the side channel, drying up the falls.

I have argued for restoring waterfalls to their natural grandeur before in this blog, and in this case the same rule applies: nature will eventually remove the diversion dam, but why not be proactive and do it now? Why deprive today’s visitors the experience of seeing the falls as it once was?

5. Thinking big… and bigger?

In an earlier article I imagined a much larger desert park centered on White River Falls. Just 100 miles and about two hours from Portland, it would become the most accessible true Oregon desert experience for those living on the rainy side of the mountains.

That possibility still exists, thanks to several puzzle parts in the form land owned by the Oregon State Parks and Oregon Fish and Wildlife (both shown in purple on the map, below) and federal Bureau of Land Management (shown in orange) along the lower White River and its confluence with the Deschutes River.

[click here for a much larger view of this map]

There’s a lot of private land (shown in yellow on the map) in this concept of an expanded park, as well, most of it held by about a half-dozen land owners. Such is the nature of desert land holdings, where typical ranches cover hundreds (if not thousands) of acres. Why did I include these areas? Because area surrounding White River Falls includes one of the least-known and most fascinating landscapes in WyEast Country, and it that warrants long-term protection and restoration.

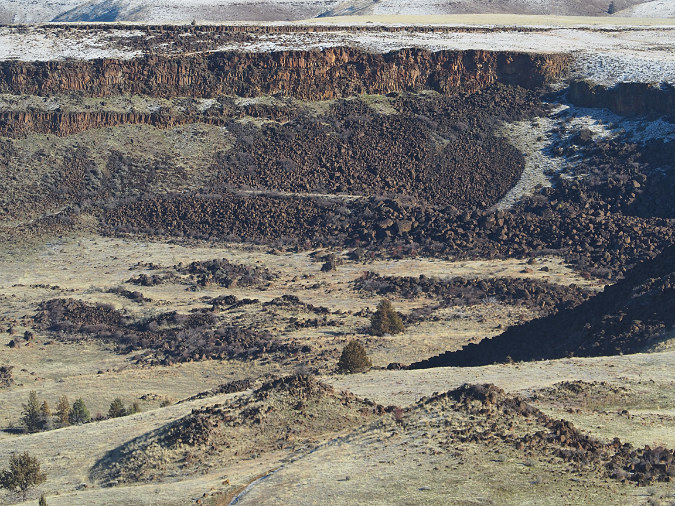

Most notable is the ancient river channel to the south of the White River Falls that I’ve called “Devils Gulch” for lack of a proper (and deserved!) name, as it is adjacent to a pair of basalt buttes called Devils Halfacre. This dry channel was formed by a massive landslide along the south wall of Tygh Valley that is nearly five miles long and more than a mile wide, and has likely been moving for millennia. The landslide may have begun as a single, catastrophic event, then continued for move slowly over the centuries, eventually diverting the White River north to its current route over White River Falls. I’ll be posting a future, in-depth article on this amazing geologic feature in addition to the following photos and caption highlights (and if any geoscience graduate students are reading this, we could use research in the form of a thesis on this area!)

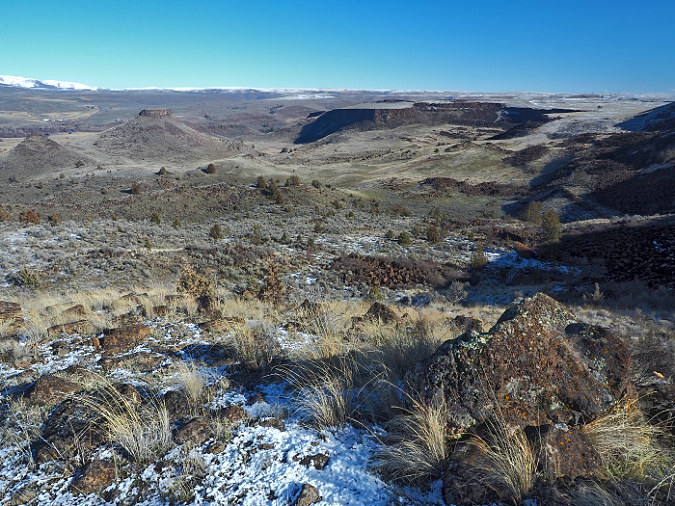

This is the fascinating view across a massive, jumbled landslide and into the former canyon of the White River before it was diverted by the landslide. Today, the river flows beyond the two flat-topped buttes known as Devils Halfacre, in the upper left corner of this photo, diverted from the dry “Devils Gulch” valley at the center of this photo

This is a closer look at the two buttes known as Devils Halfacre. They once formed the north side of the ancient White River canyon, but the debris in the lower third of the photo diverted the river north sometime in the distant past. Today’s White River flows where the ribbon of Cottonwoods marks the valley floor, beyond the two buttes. White River Falls is behind the larger butte in the center. Snowy Tygh Ridge is in the distance

Below the landslide, the floor of the ancient White River canyon is fully intact. Beyond these dry meanders where a river once flowed is today’s White River canyon, marked by the canyon wall in the upper right of this view

This view of the east end of the landslide shows distinct rows of basalt debris formed by the landslide known as transverse ridges. These ridges form perpendicular to the direction of flow, in this case from the cliffs in the upper right that formed the source of the landslide toward what was the ancient path of the White River, in the lower left

Basalt rimrock is a common sight in Oregon’s sagebrush country, but in this case, the cliffs are a scarp resulted from a massive landslide event, not gradual erosion

This view from just below the landslide scarp looks north, toward Tygh Ridge, and across more than a mile of landslide debris now covered in sagebrush and desert grasses. The landslide covers roughly the bottom two-thirds of this photo

Looking west along the landslide scarp, Mount Hood and the Cascades rise on the western horizon

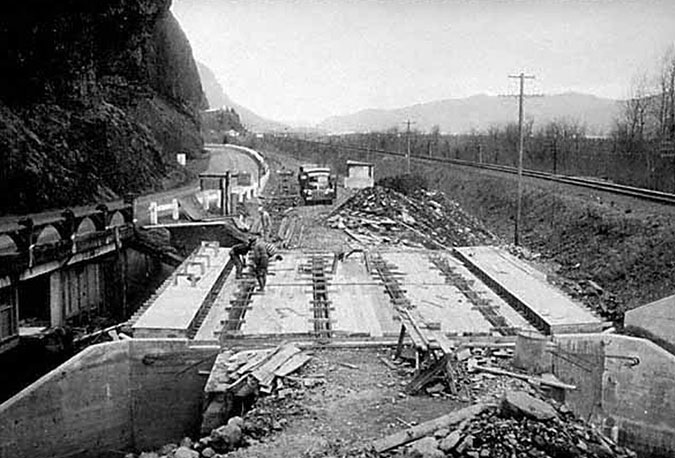

Another mostly forgotten feature in this larger park concept is a 1.5-mile section of old Highway 197 that was bypassed in the 1950s when the modern route was constructed. Because the desert does a fine job in preserving things, this piece of old road looks as if it were closed yesterday, not a half-century ago. While much of the historic road was destroyed by the modern highway, this section provides a view-packed tour of the Tygh Valley landslide from this graceful old road, including views into Devils Gulch.

The original highway from The Dalles to Maupin curved with the landscape, as compared to its 1950s-era replacement that used cut-and-fill design to make modern highways straighter and faster. This long-bypassed section of the old road is where the historic highway remnant makes a dramatic descent into the Tygh Valley. Surprisingly, even the painted centerlines still survive after more than 60 years of being abandoned!

Mount Hood rises above the highway for much of this lost highway, as well. If you simply enjoy following old routes like this, it’s a resource in its own right, but it could also be an excellent jumping-off point for hike or bike trails in an expanded park. Like accessible trails, mountain bike trails are lacking in Oregon, especially on the dry east side of the Cascades. For cyclists touring Highway 197, it could be an excellent, traffic-free alterative to a steep section along the modern highway alignment.

Cracks in the old paving are quickly discovered by moss and grasses. After making a sharp turn in its descent into Tygh Valley, the surviving section of old road points toward Mount Hood for much of its remaining length

Hundreds of mysterious desert mounds dot the slopes of Tygh Ridge, including large swarm along the north rim of the White River Canyon, downstream from the falls

Finally, there are flat-topped bluffs above the White River gorge (one that I’ve called the Tuskan Table, others north of the river) that have never been plowed, and still hold desert mounds – another topic I’ve written about before. Left ungrazed, desert mounds function like raised wildflower beds, providing both wildlife habitat and a refuge for native desert plants that have been displaced by grazing.

This is private land, so I haven’t ventured to these spots along the White River rim, but there’s a very good chance they are home to a threatened wildflower species that grows here and nowhere else in the world – the Tygh Valley Milkvetch. Scientists have documented the greatest threat to this beautiful species to be grazing, and therefore the importance of setting some protected habitat aside for these rare plants as part of the larger park concept.

Tuskan Table is a stunning, flat-topped peninsula of basalt that separates the Tygh Valley from the Deschutes River. In this view the table forms the west wall of the Deschutes Canyon. The White River joins the Deschutes just beyond Tuskan Table, in the upper right of this view

As the name suggests, the beautiful and extremely rare Tygh Valley Milkvetch grows only here, and thrives in several of the areas proposed as part of the larger White River Falls park concept (photo: Adam Schneider)

It turns out there is quite a bit of movement toward expanding park and wildlife lands in the lower Deschutes area. A few miles to the north, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife has acquired several thousand acres in recent years along the north slopes of Tygh Ridge, where a series of side canyons and ravines drop into the Deschutes River.

The federal Bureau of Land Management has also been expanding its holdings to the south, along the Deschutes River, and upstream from Tygh Valley, where the White River flows through a deep basalt canyon. In both cases, these acquisitions have been through willing seller programs, often made possible through the federal Land and Water fund for public land purchases.

Making White River 3.0 happen..?

After some lean years in the 80s and early 90s, Oregon’s state park system has seen relatively stable funding thanks to a dedicated stream from the Oregon lottery approved (and later re-upped) by voters. This has allowed the state to open the first new parks in decades – Stub Stewart in the Portland Area and Cottonwood Canyon on the John Day River. Other parks have benefitted, too, with major upgrades at iconic spots like Silver Falls State Park. So, a refurbishing at White River is certainly within reach, if not a current priority.

Rugged canyon country in White River Falls State Park

The first step is a new park master plan. This is the document that guides park managers and volunteers toward a common vision and it is created through a planning effort that includes the public, area tribes and others interested in the future of the park.

What would a new master plan look like? It might include ideas from this article, along with other ideas for accommodating the growing interest in the area and the need to actively manage the visitor impacts that are becoming visible. It would likely include plans to do nothing at all in places that should remain undisturbed, for ecological or cultural reasons.

Mostly, a new park plan for White River Falls should go big – not simply be a property management plan, but one that seeks to assemble a complete snapshot of the unique desert ecosystem that surrounds White River Falls through an expansion of the park. Cottonwood Canyon State Park is a fine model, as it was once a private cattle ranch, and is now being restored to its original desert habitat.

_________

“Make no little plans. They have no magic to stir men’s blood and probably will not themselves be realized. Make big plans, aim high in hope and work, remembering that a noble, logical diagram once recorded will never die, but long after we are gone will be a living thing, asserting itself with ever growing insistency” (Daniel Burnham)

_________

Once a park master plan is in place, new trails are the easiest and most affordable first step, especially in desert country. Much of what I’ve described here could be built by volunteer organizations, like Trailkeepers of Oregon (TKO). A new tent campground might be as simple as grading and adding water lines, also a manageable cost.

The White River has carved a deep gorge into hundreds of feet of Columbia River Basalt below the falls

Acquiring land for a greatly expanded park? There are plenty of tools and funding sources for this, but the first step is a vision described in a park master plan. The partners in making it happen would be public land agencies who already have holdings in the area, including Oregon State Parks, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife and the BLM. Tools for making it happen could range from outright purchase from willing sellers to conservation easements and wildlife easements.

While researching the area, I discovered that a private, California-based hunting club has already leased hundreds of acres of private land within the expanded park concept for use by its members. Other land trusts may be interested in this unique area, as well, and could lead the way to an expanded park, as they have in other new parks in WyEast Country.

Winter sunset at White River Falls

And how about removing the diversion dam? This would be a more complex project that would probably require an environmental review, among other questions that would have to be answered. The actual removal is less an issue, as the dam is only a few feet tall and could easily be breached. Even without a plan for removal, the diversion dam is doomed. It hasn’t been maintained for decades and will eventually succumb to the wrath of the river. If we don’t remove the dam, the White River surely will!

I’ve written about the future of White River Falls in this article, but you don’t have to wait. You can enjoy it now! Here are some tips for visiting White River Falls:

_____________

• for maximum waterfall effect and the best wildflowers, stop by in late April and throughout May, but consider a weekday – the secret is out!

• bring hiking poles for the trip into the canyon – you won’t regret it.

• factor summer heat into your trip – the hike out of the canyon can be grueling on a hot August day.

• watch for poison ivy on the boot path below the main falls – the leaves are similar to poison oak, but it grows as a low groundcover, often around boulders that might otherwise look like a great sitting spot!

• make a driving loop through the town of Maupin and a section of the Deschutes Canyon from Maupin to Sherars Falls part of your trip.

• stop at the Historic Balch Hotel in Dufur and a walk down Dufur’s main street to Kruger’s Grocery on your return trip. It’s always important to support local communities when traveling through WyEast Country.

• finally, for Portlanders, stop at Big Jim’s drive-in at the east end of the Dalles for cool milkshake (and crinkle fries?) on the long drive home

_____________

Enjoy – and who knows? I might even see you out on the trail!

Tom Kloster | February 2023