Mount Hood from Horkelia Meadow

On the east side of Mount Hood lies a pretty mountain meadow that is visited by thousands each year, but known to very few. Right about now, this little meadow is in its peak summer bloom, thanks to a low snowpack this year. The place is Horkelia Meadow, a modest, subalpine gem in the Fire Forest country of the eastern Cascades.

If you’ve ever traveled Lookout Mountain Road to the High Prairie trailhead, you’ve passed right through Horkelia Meadow, though you can be forgiven for not being familiar with the name. Years ago, a Forest Service sign marked the spot, but only a discarded signpost remains today.

Horkelia Meadow straddles popular Lookout Mountain Road

Horkelia Meadow marks an area where a layer of underlying volcanic rock forces the water table to the surface at the top of the steep western scarp of Lookout Mountain. The geology creates a number of springs in the vicinity, and at rolling Horkelia Meadow, the soils are just moist enough to keep the surrounding conifer forests at bay.

The resulting meadow is the perfect habitat for an array of wildflowers and wildlife. You’re likely to see elk and deer sign here, as well as raptors in the big trees that edge the meadow, preying on mice, voles and even the snowshoe hare that live here.

Horkelia Meadow is located in the subalpine forests on the north slopes of Lookout Mountain

Among the earliest blooms of summer at Horkelia Meadow come from a wildflower commonly known as Jessica Sticktight, Blue Stickseedof simply Stickseed. These are showy flowers that line the borders of Horkelia meadow, along the forest margins.

Blue Stickseed

Blue Stickseed flower detail

The common name “Stickseed” is self-explanatory when you look at the seed pods that form after the bloom, with each fruit covered in sticky spikes (below). When they dry out in late summer, they’re well designed to hitch a ride on passing wildlife — or your hiking socks!

But what caught my eye after a recent visit to the meadow was the botanical name for Blue Stickseed: Hackelia micrantha.Surely, there must be a connection to the naming of Horkelia Meadow?

Seed pod on Blue Stickseed (photo: California Native Plant Society)

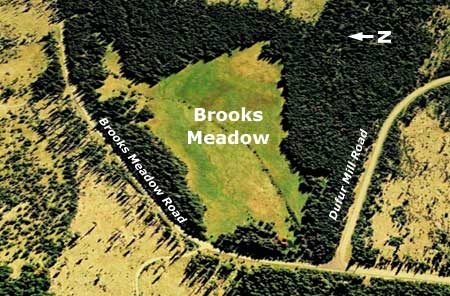

After searching through a stack of wildflower guides and web resources, I learned that Horkelia fusca or Tawny Horkelia does, indeed, grow in the area. It has been spotted at nearby Bottle Prairie and Brooks Meadow, both located to the north of Horkelia Meadow and about 1,000 feet lower in elevation.

So, a return trip was in order to see if Horkelia fuscaactually grows at Horkelia Meadow. Sure enough, it’s scattered throughout the lower sections of the meadow, far from Lookoout Mountain Road. Where Blue Stickseed is abundant throughout the meadow, Tawny Horkelia is scattered about, sometimes in open forest along the meadow edges, sometimes in dry spots near the center of the lower meadow.

Tawny Horkelia at its namesake meadow

Compared to the showy Blue Stickseed, Tawny Horkelia is a humble bystander in the meadow. These are modest little plants, happy to fill a niche in the ecosystem, but mostly noticeable to wildflower fans.

Therefore, my hunch is that a case of mistaken identity made its way onto Forest Service maps, as Hackelia micrantha— the Blue Stickseed — is lush and very prominent in the meadow during its bloom, and worthy of being its namesake. It’s also dominates along the heavily traveled upper meadow, where Lookout Mountain Road passes through, and where Tawny Horkelia doesn’t seem to grow.

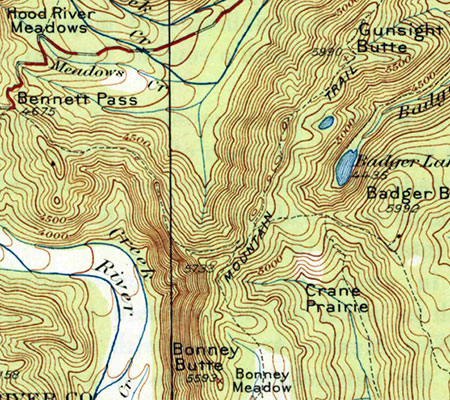

Meanwhile, it also seems that Horkelia Meadow was named fairly recently. The original primitive road was built through the meadow in the 1930s as part of the Bennett Pass Road (see this article on the blog), but Forest Service maps suggest that the Horkelia Meadow was named sometime in the early 1970s.

This is when industrial logging and associated road building went into high gear in the Lookout Mountain area (see below), and the old dirt road to Lookout Mountain was rebuilt and graveled to handle log trucks. During this period, named landmarks were helpful for logging crews navigating the tangle of new roads. I think Horkelia Meadow was (mis)named for that very purpose.

Horkelia Meadow has a bouquet of wildflower species and is a fine spot for a casual ramble to explore its secrets — hidden in plain sight! In early summer the Blue Stickseed are joined by Larkspur sprinkled throughout the meadow. Later, Scarlet Gilia, yellow Buckwheat and blue Lupine take over in a second wave of flowers.

Larkspur in early June at Horkelia Meadow

Lupine just beginning to bloom in early June at Horkelia Meadow

Scarlet Gilia in late June at Horkelia Meadow

In addition to the wildflowers, low thickets of Sticky Currant also grow on the meadow margins and along fallen trees that have dropped into the meadow (below). The summer berries on this species of currant are (as the name suggests) sticky and not edible, but the flowers put on an attractive show in early summer.

Sticky currant at Horkelia Meadow

The summer wildflower show also extends into the shade of the forests that surround Horkelia Meadow, with lush carpets of Vanilla Leaf (below), white Anemone and other wildflowers more commonly found in the wet forests along the Cascade crest.

Vanilla Leaf at Horkelia Meadow

Fire suppression in the 20th century combined with aggressive clear cutting by the Forest Service over the past four decades has disrupted much of the Fire Forest ecosystem on the east side of Mount Hood. In many areas, the result is a crowded thicket of true firs, replacing the fire-dependent species of Ponderosa pine, Western larch, Lodgepole pine and Douglas fir that used to dominate. This, in turn, has triggered a cycle of beetle infestations among the crowded, weakened fir forests across the mountains of Eastern Oregon, often followed by catastrophic fires that kill even the fire-dependent tree species.

The good news is that the Forest Service has begun thinning some of these unnatural forests in an effort to restore the Fire Forest structure, including the use of controlled burns in some areas (see “Fire Forests of the Cascades”) Over time, this could help restore the natural forest ecosystem.

A walk around Horkelia Meadow shows remnants of the old Fire Forest cycle that once dominated the area, creating open, park-like forests under towering trees. If you look closely, you can even find a few traces (above) of the last forest fire to sweep through the area, decades ago, when the forests were much different than today.

A trio of fire-dependent Western Larch along the east margins of Horkelia Meadow

Whether fire returns to the areas as a planned burn or natural event, the Fire Forest species are still here and ready to resume their role as the dominant trees of this ecosystem… if we will allow it.

Exploring Horkelia Meadow

[Click here for a handy, large map to print for your tour!]

The old Fire Forest remnants scattered around Horkelia Meadow, some living and some standing as skeleton trees, provide easy landmarks for a tour. The starting point for exploring the meadow is the high point at the east end of the meadow, just off the Lookout Mountain road (from the recommended parking spot described at the end of the article, follow the road uphill for 100 yards).

At this upper end of Horkelia Meadow stands a gnarled, burly skeleton of what I call the “Big Bear Tree” (below), as it looks like it might be lumbering off into the woods, having lost his top. The low, dense branching on this ancient skeleton suggests this was an enormous Englemann spruce, a species that thrives in forests along the Cascade crest, especially along meadow margins. A living Englemann spurce can be found at the lower edge of of the main meadow, below.

The “Big Bear” skeleton tree at the upper end of Horkelia Meadow

In early summer, the meadows around the “Big Bear Tree” are also filled with Blue Stickseed and Larkspur.

Heading downhill and across the road, pass a larch grove and head toward the bones of a very large, double-trunked Ponderosa pine (below). I call this old tree the “Patriarch” because it clearly ruled over Horkelia Meadow until fairly recently. Air photos show this giant still standing and alive in 2005, but toppled by 2010. The amount of bark left on the trunk is a good indicator of how recently this tree died.

“Patriarch Tree” at the center of the meadow, a huge, double-trunked Ponderosa pine that has toppled within the last decade or so

Newly toppled Patriarch Tree at Horkelia Meadow

Next, head downhill into the main meadow, located to the west and tucked away from the road, out of sight to passing travelers. Here, a large, multi-trunked Ponderosa Pine I call “The Flyswatter” towers over the scene at the north end of the meadow. This big snag is a favorite of raptors, especially owls, and is actually two snags, with the tall, single-trunked skeleton of what was likely a Grand fir wrapped in the bleached limbs of the old Ponderosa.

As you walk toward “The Flyswatter”, look for a couple of handsome Lodgepole pine growing along the east margin of the main meadow, another important species in Fire Forests.

“The Flyswatter” skeleton tree and the lower part of Horkelia Meadow

“The Flyswatter” tree skeleton

Just beyond “The Flyswatter” (and over a large, collapsed trunk you’ll need to navigate) is the mostly hidden northwest meadow. This pretty spot used to be guarded by another large Ponderosa pine that has long since become a skeleton, and now lies across the meadow. Based on air photos, it looks to have fallen sometime in the 1970s (below). I call this one the “Dragon Tail” tree (below).

The “Dragon Tail” tree in the hidden northwest meadow

Returning to the main meadow, a pair of big Ponderosa pine come into view (below) at the top of the slope. I call these the “Odd Couple”, as one is a nearly perfect Ponderosa specimen, while its twin is anything but, with a twisted, leaning top and huge, gnarled branches. Both were once in the shadow of the massive “Patriarch Tree”, whose skeleton lies just a few yards away.

The heart of Horkelia Meadow, with the “Odd Couple” to the left of center

The “Odd Couple” at the center of Horkelia Meadow

The grassy, shaded landing between this pair of Ponderosa makes a nice spot to relax and enjoy the surrounding meadow. From here, you can appreciate the tortured life of the southernmost tree of the pair. The deep scar running down the west side of its trunk and deep wound at the base of the trunk suggest a lightning strike — a common cause of demise for big trees that grow in exposed places like Horkelia Meadow (below).

Scarred trunk of the southernmost “Odd Couple” pair

Lightning may have taken out the nearby Patriarch Tree, too — seen here from the Odd Couple:

The “Patriarch Tree” skeleton lies just beyond the “Odd Couple”

Look up into the tortured twin and you can see (below) that the main trunk is really a surviving limb that took over to replace the main trunk after the original top was destroyed — whether by lighting or simply a windstorm.

The curvy, leaning top of the southern “Odd Couple” twin

The base of this old tree (below) shows another familiar trademark of big Ponderosa pine, a broad dome of “puzzle pieces” that have accumulated around the tree over the decades. These platforms of accumulated bark chips and pine needles give these handsome trees their park-like appearance, as if the meadow has been carefully trimmed around the tree.

Ponderosa bark piled up to form an apron around this giant at Horkelia Meadow

Ponderosa don’t choose to be multi-trunked, but they can adapt this way when topped by weather or lightening. The extra load of lateral limbs adapting to become a replacement trunk results in some very impressive trees, with upturned limbs 18″ or more across emerging from the trunk of the twisting “Odd Couple” twin (below). Over time, though, these trees are still more prone to collapse than single-trunked trees from heavy snow accumulation or wind on their bulky branch structure.

Heavy-duty limbs on the more gnarled of the “Odd Couple” Ponderosa pair

The bark on Ponderosa pine is both fascinating and beautiful. The puzzle-like flakes (below) continually shed as the bark on the tree grows. The dark furrows in the bark form as the tree expands under its thick bark jacket, pulling it apart

Bark detail on the more gnarled of the “Odd Couple” Ponderosa pine

Ponderosa pine bark on a mature tree can be several inches thick, and this is the main defense against fire, a needed and necessary part of the Fire Forest ecosystem. The combination of protective bark and high crown allows the biggest trees to survive multiple fires and thrive to produce offspring after each successive burn. In this way, the recently fallen “Patriarch Tree” could easily be the parent of the “Odd Couple” and other big Ponderosa pine around Horkelia Meadow.

Recent cones from the more gnarled twin of the “Odd Couple” Ponderosa pine at Horkelia Meadow

The gnarled sibling in the “Odd Couple” has had a harder life that its twin, for sure, but it continues to generate cones and seeds (above). In the end, that’s all a Ponderosa Pine lives to do, no matter how funky its shape. Over time, the toughest, most resilient trees decide the future of the forest with their offspring.

Old fire rings between the “Odd Couple” Ponderosa pine trees

If you do find yourself having a snack or picnic under the “Odd Couple”, you won’t be the first. Nearly lost in a thick carpet of Ponderosa needles is a pair of old fire rings (above). How long since these were uses? Decades, perhaps? They could even date back to a time when herders brought sheep up from the Dufur Valley to graze the slopes of Lookout Mountain in the early 1900s, and have since been forgotten in this little meadow (and just in case, please leave them be as remnants from an earlier time).

So, where’s the mountain?

Mount Hood from the lower south meadow

The upper and main meadows offer occasional peeks at the top of Mount Hood, but the best views are from the south meadows, located downslope from Lookout Mountain Road, beyond a curtain of trees. Here, the western scarp of Lookout Mountain begins to fall away quickly, with the south meadows perched above steep forested slopes, below.

To reach the hidden south meadows, head across the main meadow through a gap in the trees that is directly in line with the Odd Couple. Here, you’ll arrive at the top of the upper south meadow, and you can then meander downhill through another gap to the larger, lower south meadow. Mount Hood Views abound here, and the lower meadow is also a fine spot for a picnic.

Bluegrass Ridge from the lower south meadow

The view from the lower south meadow also includes Blue Grass Ridge, which forms the eastern edge of the Mount Hood Wilderness. From here, you can see the traces of the 2006 Bluegrass Fire that burned most of the crest of Bluegrass Ridge, and the 2008 Gnarl Fire that burned the eastern slopes of Mount Hood all the way to Cloud Cap Inn, on the northwest horizon.

These recent burns are recovering quickly, with a bright green understory of Western larch, Lodgepole pine and White pine emerging under a ghost forest of bleached snags. While these were the first fires to burn the east slope of the mountain in more than a century, the landscape they left behind is what the area looked like before fire suppression in the 20th Century — a diverse mosaic of mature and recovering Fire Forests.

Shark fishing in the south meadow… can you see “Jaws”?

There are a few more name-worthy skeleton trees along the way as you drop down to the lower south meadow. First, you’ll pass a bleached stump that I originally called “Jaws”, but then spotted a “fisherman” complete with a deep sea fishing rod just up the hill — and thus, “Shark Fishing” for this trio (above).

At the top of the lower meadow a pair of stout Ponderosa skeletons are the “Goal Posts” (perhaps because it’s World Cup season). The meadows just below the “Goal Posts” have an excellent mix of wildflowers right now, too, and are where the Scarlet Gilia were in bloom on my last visit.

The Goal Posts in the lower south meadow

I know it’s a little silly to name all of these ghost trees, but hopefully it will help navigate the meadows if you choose to visit. It’s also a way for me to stop and appreciate the story each of these silent old patriarchs has to tell… and it’s just fun, too!

Horkelia Meadow at Work

I used to worry that fallen trees would eventually consume precious meadows with the accumulating debris, but it turns out that the meadows do just fine in consuming the trees, instead. One phenomenon you might notice as you explore Horkelia Meadow is log traces. These look like very straight trails, at first, but are really just places where fallen trees have nearly been absorbed into the meadow, and the grasses and wildflowers have all but covered what’s left of the fallen log.

There’s a prominent log trace in the upper south meadow that tells the story nicely. Fuzzy air photos from the mid-1990s (below) show a pair of fallen, bleached skeleton trees lying intact across the meadow. These trees could easily have stood as snags for decades after they died, but once on the ground, trees begin to decompose much more quickly.

Fifteen years later, in 2010, air photos show that the smaller of the two skeleton trees had really begun to fall apart, while the larger tree was mostly intact and still many of it’s bleached limbs.

By last summer, however, air photos show the smaller tree had faded to a line of decaying wood in the meadow and the larger tree has lost most of its remaining limbs over the previous seven years. Today, the smaller tree has left just a trace in the meadow, and will soon completely disappear.

This cycle has played out countless times at Horkelia Meadow over the centuries, with many trees falling and fading into the meadow, each adding more valuable organic matter to the soil in the process. While new trees continue to emerge along the meadow margins, they’ll eventually suffer the same fate, too. The meadow is holding its own in this battle with the surrounding forest!

Young Grand Fir growing where an old giant once stood

As you explore the lower south meadow, you may notice a lot of blowdown along the lower margins of the meadow. These trees weren’t brought down by old age or meadow moisture, but instead were victims of a late 1980s clearcut. The extent of the clearcut is obvious on the map at the top of the article, and as you can see, it is littered with blowdown.

The fallen trees in the clearcut all point uphill. That’s because the prevailing winds coming from the west pushed them that way after the surrounding forests were logging, leaving the remaining trees suddenly exposed them to the full brunt of winter storms. Some of these could have simply been left behind by loggers — perhaps they too small to bother cutting — and larger trees might have been left to reseed the clearcut. Most have since toppled.

Heavy blowdown on the edges of the 1980s Horkelia clearcut

Other blowdown along the margins of the meadow occurred in areas where trees were clearly left standing as a failed “buffer” to protect the meadow — a common practice that has destroyed thousands of trees along similar clearcut margins throughout the Mount Hood area. And after thirty years, the clearcut is just beginning to recover from logging, yet another reminder that high elevation clearcuts in the Cascades were never a sustainable practice, and never should have happened. Let’s hope we’ve seen the end of it here.

If you walk through the old clearcut, you’ll also notice hundreds of what look like small, nylon mesh bags sprinkled about. These were used to protect new seedlings when the clearcut was stocked with a new “plantation” of trees. It’s another failed effort, as most of these seedlings did not survive the harsh winters and dry summers here.

Non-biodegradable seedling nets from the 1980s logging at Horkelia Meadow

Unfortunately, you will also notice these little mesh bags throughout the lower south meadow. Whether intentional or simply through sloppy incompetence, the Forest Service actually “replanted” a natural meadow when the adjacent clearcut was replanted. What were they thinking? Fortunately, all that survives are the dozens of nylon bags, and the meadow remains intact and thriving today.

If you’re looking for a community service, scout troop or other group project and want to help Horkelia Meadow out, I suspect the Forest Service would give you the okay to retrieve these bags from the meadow. Unfortunately, they are not biodegradable, so will be there until they are removed. They’re held down by metal stakes, but can be pulled out by hand if you wear a pair of heavy gloves. Give the Hood River Ranger District a call if you’re up for the task!

How to get there…

Horkelia Meadow is easy to visit, and makes for a nice add-on to your trip to Lookout Mountain or other hikes in the area. It’s best visited in morning or evening, as the southwest exposure is often hot during the summer. You can walk the margins of the meadow in under an hour and gain a nice appreciation of flora, large and small, of this lesser-known spot.

All that’s left of the old Horkelia Meadow sign is this old signpost

To find the meadow, follow paved Forest Road 44 about 3.5 miles from the Highway 35 junction, toward Dufur. Just beyond the busy Surveyors Ridge Trailhead (on the left), watch for the poorly signed Lookout Mountain (Road 4410), on the right. Horkelia Meadow straddles this dusty, sometimes bumpy gravel road 1.3 miles from the Forest Road 44 junction.

Park at the marked Forest Road 140 spur

I recommend parking at the junction with primitive road 140, on the left as just as you reach Horkelia Meadow. There’s room to park here without impacting the meadow wildflowers, but be sure you don’t blog the spur road.

To tour the meadow, walk up the road to the upper end, watching for the “Big Bear” skeleton on the left, then use the map at the top of this article to find your way.

Botany class exploring Horkelia Meadow

To help protect the area, please follow these basic rules of meadow etiquette when exploring, as there is no developed trail at Horkelia Meadow:

- Hose or brush off boots before every hike to help slow the spread of invasive species, especially when hiking off-trail

- Don’t gather flowers, seeds or anything else in the meadows — “take only memories (and photos) and leave only footprints”

- Don’t step on flowering plants, step between them

- Try not to follow faint paths you might encounter in the meadows — while they are likely deer or elk trails, repeated walking on them could make them permanent

- No fires, dogs, loud voices or drones (aargh!) that might disturb the wildlife and other visitors when venturing off-trail, especially in meadows

You’ll undoubtedly have the place to yourself — but if you should see a car parked along the road, consider stopping another time for your visit.

Thanks, and enjoy Horkelia Meadow! Or is it Hackelia Meadow…?