The recently collapsed cliff wall along the Collawash River

We’re experiencing a bit of a geologic moment in WyEast Country, of late. A series of major cliff collapses in recent years along well-known streams has given us a unique opportunity to see the raw forces of nature at work, shaping the landscape in real time, and also to witness nature rebounding after these violent events. Most of these recent collapses have been along streams in the Columbia River Gorge, but sometime over the past two years, the Collawash River joined the trend.

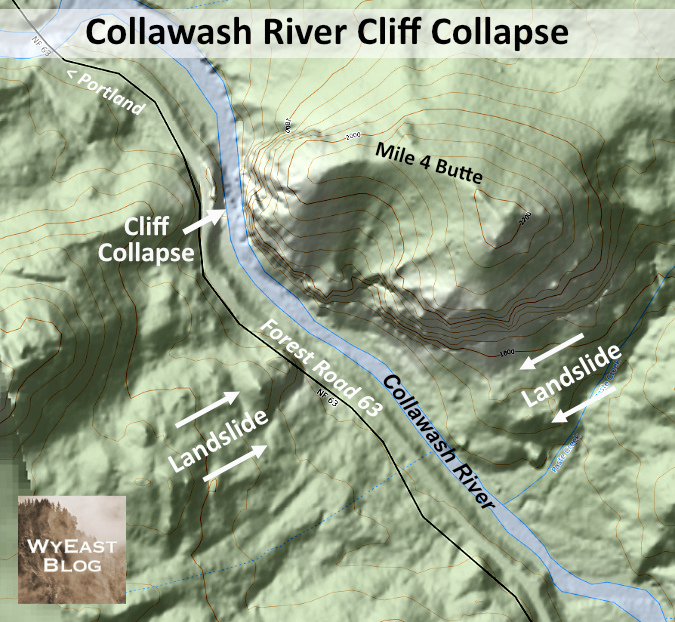

The Collawash River is special. Even in a region known for pristine, spectacular rivers, the Collawash stands apart. That’s in large part due to its unique geology. The Collawash River originates in the remote, rugged Bull of the Woods Wilderness and tumbles through a deep, forested canyon, made perpetually unstable by ancient landslides that are literally pulling the steep mountain slopes on both sides toward the stream.

Massive landslides create a continually changing landscape along the rugged Collawash River

The result is very active landscape along the Collawash, with hundreds of massive boulders marking past landslide events scattered along its course. The ongoing landslides, combined with recent forest fires in the Bull of the Woods Wilderness have also created epic logjams where thousands of trees dropped into the river have accumulated behind these boulders in huge piles.

The erosive action of the Collawash River against the force of these landslides has the effect of a conveyor belt. During high water, the river periodically removes debris from the actively eroding toe of the slides, which in turn, triggers more sliding. This cycle has been playing out for millennia on the Collawash, gradually carrying material from the slides downstream into the Clackamas River, then beyond, leaving only large boulders behind. In time, even the largest of these boulders eventually give way to the elements, and are carried away by the river in pieces.

The dramatic, evolving scenery along the Collawash River is shaped by massive, collding landslides pushing into the river canyon from two sides

One of the many landslides feeding into the Collawash River

[click here for a large version]

Along the way, these landslides also push the Collawash River against solid rock walls along its steep course, allowing the river to gradually cut away at these, as well. Like the erosive process described in this recent article, a solid rock wall that has been persistently undercut by the river eventually collapses, adding still more boulders and loose debris to the river.

I unexpectedly came across just such an event this year along the Collawash River. The first clue was an eerie slackwater (shown below), with streamside Red Alder inundated under several feet of perfectly still, turquoise water. Just downstream was the answer to this strange anomaly. A massive rock slab had split from a tall cliff along the east bank of the river, crashing into the stream and creating a debris dam that formed a temporary lake on the Collawash.

The eerie, still pool in the Collawash impounded by the recent debris pile

The new debris pile in the foreground and the impounded, temporary lake on the Collawash

The river has since breached the debris pile and is now beginning to carry away fine debris. Note the inundated Red Alder trees in the background

Based on available air photos, the collapse occurred sometime between July 2021 and August 2023 — the 2021 image shows the free-flowing river and the 2023 version clearly shows debris the cliff collapse. While these events can occur at any time of year, those we have seen in recent years have mostly happened during the wet winter months, when the forces of erosion are at their peak.

Based at the state of the debris pile, I would guess that this cliff came down sometime in the winter 2021-22, roughly two years ago. Why this guess? Because with events like this, the debris pile is usually loose enough for the stream to initially flow under it – like a sieve – until the pile settles and when fine material carried in the stream begins to plug small gaps in the settling pile. The other clue is the lack of fine material on top of the pile – the Collawash has clearly had some time to scour the pile of small debris during at least one season of high water.

(Update: per Ian’s comment, below, the Forest Service estimates the collapse to have occurred in February 2023 — a full year later than my guess! They also reported that at that time, the entire river was flowing through the debris and had not yet overtopped it, where today a significant amount of the flow is overtopping the debris. The Collowash is making quick work of this blockage!)

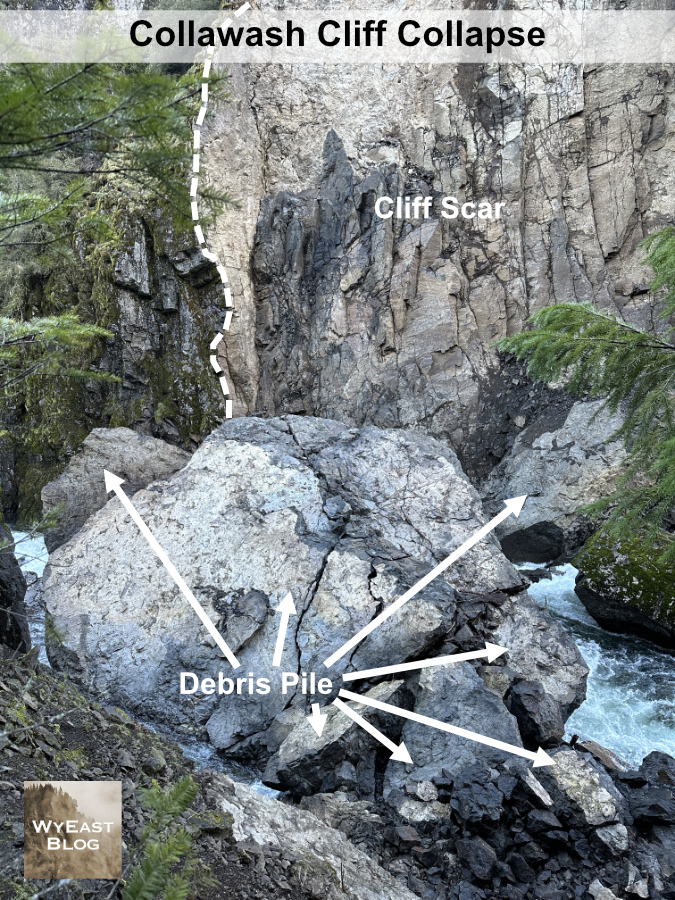

Though a portion of the river’s flow is now cresting the debris pile, much of the flow is still flowing through the loose debris

As with other cliff collapses, several very large pieces of intact cliff survived the fall, but these are already beginning to buckle from their own weight. As the stream continues to churn away at the smaller debris in the pile, the huge boulders sitting on top face enormous stress when the underlying debris beneath them shifts. An especially impressive, house-sized slab that is the largest among the boulders to survive the collapse (below) is already showing large stress cracks. It, too, will eventually break apart as the debris pile continues to shift and erode.

The largest of the intact cliff sections is this behemoth, roughly the size of a small house. Stress cracks are already forming as gravity and the shifting, eroding debris flow beneath the boulder continues to move

Downstream from the debris pile the Collawash River roars through a new Class 5 rapid created by the debris (below). The erosive energy of this steep, newly-formed rapid is immense. Over time it will erode the debris pile from below, continually pulling material from the collapse downstream and allowing the river to cut more deeply into the remaining pile.

New Class V rapids formed below the debris pile where the Collawash is now much steeper than before

Looking downstream from the collapse section, giant boulders in the distance (now moss-covered) from previous collapses reveal the most recent event as just another in a perpetual process of river erosion here

The erosive energy now concentrated in the new rapids just below the debris pile is hydro-physics in action. The panoramic view of the collapse (below) tells the story: the temporary lake on the right hides a series of pools and rapids that existed upstream before the slide, and this energy has now been displaced to the new rapids in the downstream section, just below the slide.

Panoramic view of the cliff collapse showing the impounded lake (right) upstream and the new rapids (left) downstream created by the debris pile at center

[click here for a large version]

This amount concentrated energy of focused on the lower end of the new, unconsolidated debris pile means the river will quickly win the battle of rock versus water that is on full display here. Eventually, this will become what kayakers call a “boulder garden”, eventually draining the temporary lake and leaving only a few of the largest boulders in place to mark the site of cliff collapse. This is only the latest of many such events at this narrow bend in the Collawash River, and it won’t be the last.

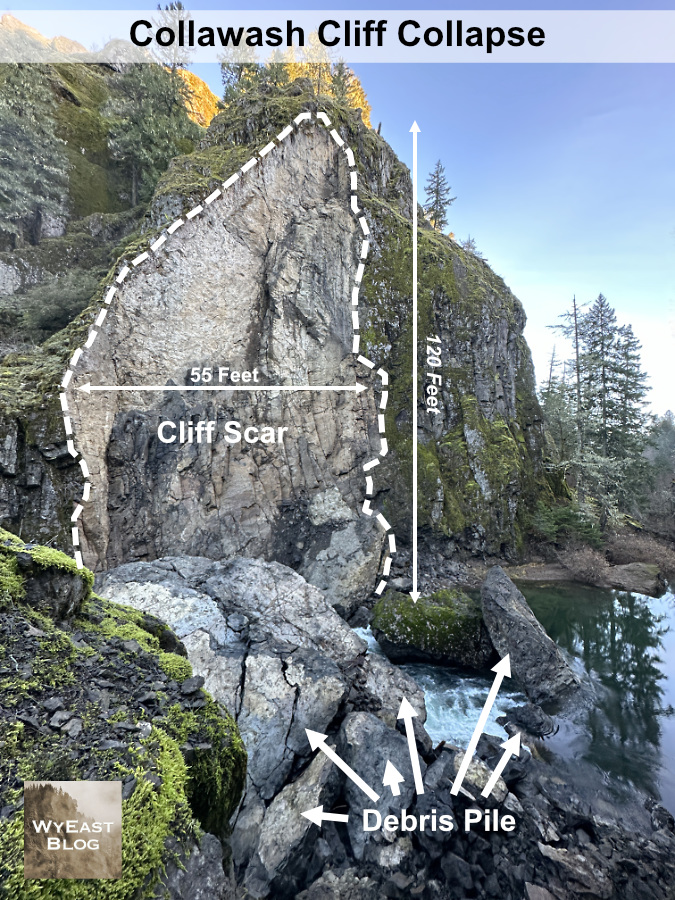

The following schematics show the newly exposed cliff scar and the debris left by the cliff collapse in more detail:

The collapse created a 120-foot vertical scar in the cliff

The debris pile from the collapse is dominated by this massive 25-foot wide boulder

In researching this article, I stumbled across an image captured by outdoor writer Zach Urness in the summer of 2019 at the popular swimming hole just below these cliffs. To my amazement, you can plainly see that a prominent crack had formed in the cliff face, and matches the outline of the eventual collapse! I’ve marked it with a series of arrows in the photo below.

View of the Collawash River cliff before the collapse with arrows marking the obvious crack that was forming (photo: Zach Urness)

Closer view of the Collawash River cliff before the collapse with arrows marking the crack that would eventually lead to the collapse (photo: Zach Urness)

Zach’s photo also shows how this spot in the stream was already littered with large boulders from prior collapses before the collapse. There’s no way of knowing when these earlier events occurred, but we do know from witnessing the latest collapses here and elsewhere in WyEast Country that they are more common – and constant – than we once thought.

The lack of photos or reporting on the collapse has a silver lining: Zach’s photo was taken from just above the Little Fan Creek picnic area, located at the confluence of the main Collawash and Hot Springs Fork. This area is especially popular with families in the summer months, with crowds of people floating and swimming the many pools in the river, and where a summer event might have had deadly consequences.

How to see it for yourself…

The graceful Collawash River Bridge was constructed in 1957 as part of logging heyday in the upper Clackamas River watershed

The recent cliff collapse on the Collawash River is easy to visit if you’re looking for a weekend drive. The winter off-season is the best time, too, as the Clackamas River corridor is popular and often busy during the spring and summer months. To reach the site, head up the Clackamas River Highway (OR 224) for 26 miles east of the town of Estacada to the Ripplebrook ranger station and campground, Here OR 224 becomes Forest Road 46. Continue for another 3.5 miles on FR 46 to an obvious (but usually unsigned) junction with the paved Collawash River Road (Forest Road 63).

Turn right onto FR 63, and be sure to take your time along this stretch. Here, the road hugs the Collawash River through an exceptionally scenic and geologically interesting areas. You will immediately cross a beautiful arched bridge over the Collawash as you enter the river’s narrow lower canyon on FR 63. Views of dramatic cliffs, river rapids and impressive old growth trees are at every turn, with frequent pullouts for stopping.

Autumn scene along the Collawash River Road

At about the 4-mile mark you will reach another junction, where paved Forest Road 70 heads right to well-known Bagby Hot Springs, located on the Hot Springs Fork of the Collawash River. Stay straight on FR 63 from this junction and immediately cross the Hot Springs Fork on second bridge. The recent cliff collapse is just upstream from here, so watch for an obvious boulder perched on a pile of moss-covered rock on the east side of the road (shown below). This is where the collapse occurred.

There’s room for shoulder parking next to the perched rock, and the best view is from the upstream side of the big boulder, on top of the rock pile. Use care scrambling up the rock pile – there’s a steep drop on the opposite side!

While it looks poised to roll onto my car, this boulder is from an earlier cliff collapse that occurred well before the Collawash River Road was built in the 1950s. The best viewpoint of the latest collapse is from the top of this rock pile, next to the big boulder

Though the Collawash River was mostly spared by the Riverside Fire that swept across 138,000 acres in the Clackamas River watershed in 2020, the Clackamas River Highway route to the Collawash River travels through much of the burn. While this might sound a bit bleak for a scenic drive, it’s a great opportunity to fully appreciate the scope of the burn and watch the beginnings of the post-fire forest recovery here.

The Riverside Fire was the third and largest of three human-caused fires to sweep through the Clackamas River canyon over the past two decades. While fires are a natural and necessary element to forest health in the Pacific Northwest, it’s also true that human-caused fires are burning the Clackamas River basin (and many other forests in the Pacific Northwest) at an unsustainable.

The human-caused Riverside Fire roared across the Clackamas River area in September 2020 burning 138,000 homes and dozens of structures in its path

Human-caused fires are also killing old-growth riparian trees that have survived centuries of wildfires. Why? In part because of the intensity of these recent burns as a result of decades of fire suppression, but also because riparian areas were often be spared in the past by natural, lightning-sparked fires that typically began on exposed, drought-stressed ridgetop forests – not in moist rainforest canyons, where all three of the human-caused fires on the Clackamas started.

The Forest Service is still gradually reopening the many campgrounds and picnic areas along the Clackamas River that were affected by the burn, so you are likely to encounter logging operations where trees deemed “hazardous” are being removed by contract crews. These projects are well-signed and easy to avoid if you’re following the main route.

The Forest Service is still logging fire-killed or weakened trees like these along major forest roads in the Clackamas area as “hazard trees”

For a longer tour, you can continue further upstream along the Clackamas River Highway from the Coillawash River Road junction. The highway hugs the Clackamas River for another eight scenic miles, with pullouts along the way to appreciate the views. This section of the highway passes Austin Hot Springs, an interesting area, but also a private inholding within the national forest, and not open to the public.

Above the Collawash River confluence, the main Clackamas River is unburned and a reminder of what the lower canyon looked like before the 2020 Riverside Fire

As you explore the area, you may begin see each vertical cliff and outcrop with new eyes as – perhaps – the next real-time geologic event! Chances are slim that any of us will witness such an event, but seeing the aftermath of the Collawash River collapse gives a new appreciation for the constant natural processes that continue to shape the scenery around us.

Enjoy!

_______________

Tom Kloster | January 2024

According to the Mt Hood National Forest Facebook page this collapse happened sometime around early Feb ’23.

LikeLike

Thanks, Ian – good find! I’ll update accordingly.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Collawash River is quite a find. I have lived 60+ years in Oregon and had never heard of it. Would it be possible in the future to provide info on how to get to the places you talk about. I live near Hood River and don’t often think of the areas SW of Mt. Hood

LikeLiked by 1 person

January 14, 2024

Hello Tom,

Your latest WyEast Documentary, “Collawash River Cliff Collapse!” is truly spectacular!

Keen visuals once again with before and after photography, including identifying the pre-collapse clue evidenced by the large vertical crack in the rock face. You provide great geological narrative accompanied by photographs with overlays and graphics identifying post-collapse boulder cracking and describing subsequent events sure to develop. There’s a topographical map, along with aerial and ground photographs, with all manner of descriptive overlays, graphics, and dimensions, even!

I always have one rule about new swimming holes, especially when jumping into them from a point above: I have to be able to see the bottom. Now, with all credit to you, I’ve added a second rule, one I’ve thought about in caves: look for cracks in rock faces and boulders to evaluate potential for catastrophe.

How beguiling that placid pool prior to collapse!

You’re right, the new rapid at the upper end of the former swimming hole appears to easily rank a Class V classification, at least.

From your scouting position photos, it looks like there might be one or more must-make moves. And, a lot of potential wrap or pin spots at rocks seen and unseen, where rescue would very difficult, even with pre-run rescue setups in place. Maybe a Class V if successfully run, with potential for Class VI+ consequences if not. Short, quick, and exhilarating if you make it, if you don’t, well, you’ll be in the news and a Youtube either way.

With outstanding narrative and accompanying great visuals, you are truly in class of your own, Tom. Naturalist, Geologist, Guide, Documentarist, and Advocate, pretty remarkable.

My favorite photograph?

The Horseshoe Bend scene. Tranquility becoming mayhem “just around the corner” which, of course, is a favorite answer to “when are we going to pull over?”

In this case, the transformation is instant, much like the collapse event itself must have been.

I’ve seen a lot of great “Horseshoe Bend” photographs, but yours has leapt to the top. It warrants consideration as a candidate for the 2025 calendar.

Thank you Tom, I really enjoyed it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the kind comments – much appreciated! It sounds like you are a seasoned river runner, so I especially appreciate validation on the class ranking for the new rapid — just a guess on my part based on it looking pretty burly in there! But given that kayakers jump from 100-foot waterfalls these days, I’m guessing it has already been run?

I’m also curious if “Horseshoe Bend” is already a kayaker’s name for this spot? In researching the piece, I did read these excellent kayaker accounts for the upper Collowash (for another piece I’m working on), and this is where I first learned about the massive logjams upstream:

https://www.oregonkayaking.net/rivers/collowash/collowash.html

…and a more recent account:

http://mthoodh2o.blogspot.com/2014/05/upper-collawash.html

Appreciate you stopping by, River Runner!

LikeLike

Ron Calvin, thank you for stopping by! The best way to get to the Collowash from Hood River (in a day trip) would be to come through Government Camp, then down to Sandy on US 26. As you come into the “downtown” Sandy one-way couplet, watch for a sign that points to OR 211 South to Estacada/Molalla. Turn left here and follow OR 211 for a few miles to the junction with OR 224. Turn left again and follow OR 224 to Estacada, then into the Clackamas River canyon per my instructions in the article. The Clackamas and Collawash are usually snow free year-round in the canyons, but it’s still worth checking with the Forest Service before you go.

LikeLike

…and I found one more kayaking report that seems to describe this spot as the “Chute to Kill” (great name!) based on the third photo in their report (compared with photo 10 in this article) and the description of this spot being just above the Hot Springs Fork confluence:

https://www.oregonkayaking.net/riverframe.html

If so, it’s a great archive of what this used to look like before the collapse! Kudos to the kayakers for all the great web content they provide!

LikeLike

Hello Tom,

“Horseshoe Bend” is a term frequently used to describe turns of a similar shape in many rivers. There are probably as many turns in rivers named “Horseshoe Bend” as there are lakes named Blue, Clear, and Lost. In Oregon, there are several lakes sharing these three names!

When I referred to your photograph “leaping to the top” of my favorite “Horseshoe Bend” photographs, I was including the entirety of rivers with horseshoe bends I’m familiar with, including, and probably the most iconic “Horseshoe Bend” on the Colorado River.

Picking favorites is really a subjective exercise. What I like about your photograph is the way you capture two very different personalities of the same river, at exactly the middle, or horseshoe bend, where the transformation occurs. To me, it’s wondrous.

I enjoyed checking out the two links in your reply with trip reports of kayaking the Upper Collawash, fourteen years apart.

The first, an Upper Collawash trip report on oregonkayaking.net, was written in 2000!

Those guys, and their predecessors who had previously done that run, and many other steep creek runs of similar challenge, were considered “hair” boaters, a then-small group of paddlers really pushing the envelope of what types of runs, especially on steep creeks, that could be successfully navigated.

Watercraft really began to evolve in the 1980’s, along with the skills of men and women who paddle them.

Today’s watercraft and paddle designs, and the expanding group of highly-capable paddlers at increasingly younger ages, are just amazing! And thanks to Youtube and blogs like your yours, their accomplishments achieve public notice, and record.

Laws pertaining to waterways often have stipulations pertaining to “navigability” that classify them as “public waters” which often contributes to better protections of such waterways, especially when they cross or abut private property.

Creeks and rivers that can be navigated have their chances for protections increased.

I hope in the future Collawash documentary you’re working on that there might be room to consider “The Sentinels” shown in one of the photographs included in the mthoodh2o.blogspot trip report of the same Upper Collawash run, fourteen years later in 2014, by another group of skilled paddlers.

Those ghost trees intrigue me, in much the way a similar group of ghost trees in the Columbia River are noted in the Lewis and Clark journals. It seems Clark, particularly, was fascinated by the presence of those trees, dead and decaying, yet still standing where they had once lived, which, due to a past event he theorized about, resulted in the ground the trees were rooted in being completely submerged while they were still living.

Tom, you could provide a really great account of “The Sentinels” and I sure hope you consider it.

Just before I posted this reply, I saw your third posted link to the Upper Collawash, with a trip report from 2002 featuring the section, with photographs, described in your Collawash River Cliff Collapse! documentary.

I’m with you, Chute to Kill is a great name, and even more appropriate now with what sounds like a sieve at the top of the run resulting from the cliff collapse.

You may already know this, the first person to run a rapid, a first descent, gets naming rights.

Often the names are clever and respect the challenge, like Chute to Kill. Other times, an outstanding rapid has gotten an unfortunate moniker, like the denigrating Toilet Bowl on the Clackamas River. I’ve run and re-rerun this rapid countless times at the end of a day running the Upper Clackamas, until I’m totally exhausted, about the time the sun goes down behind the firs, and I take out right below. It’s huge volume, pure thrill, and exhilaration. I’ve never thought of the surroundings or my experience in the rapid being similar to any part of a commode.

Incidentally, and no surprise to me, your photograph of the horseshoe bend at the top of Chute to Kill Rapid beautifully reflects the following gem of insight you expressed in 2021:

“Do rivers have a sense of humor or experience joy? As I looked down upon the White River sparkling and splashing down its new channel this summer, it seemed to be thoroughly enjoying the pure freedom of flowing wherever it wants to. It’s yet another reminder that “nature bats last”, and in WyEast country, the mountain – and its rivers — will always have the final word.”

Hurray for that!

And, hurray for the outstanding Naturalist who felt that!

LikeLike

Thanks for the great comments, Rafterkayaker! Super insightful and appreciated! I do plan a couple of pieces focused on the Collawash and Hot Springs Fork — a two-parter — and I’ll definitely comment on the “sentinels”. They are great examples of drowned forest. If they were leaning at a collective angle, they might suggest being part of a slow landslide and having slid into the river as a raft. That can happen, but when it does they don’t stay standing for long. Thus, I’m quite certain these were drowned in place by a landslide event downstream that raised the river level, just as you suggested with the famous drowned forests on the Columbia (also from a colossal landslide).

Thanks for stopping by! 🙂

LikeLike

Hello Tom,

Freezing rain is coming in for a landing, ironically, moments after power was restored following a four day outage along our stretch of the river. Who knows what awaits…

I’m already looking forward to your future two-parter on the Collawash and Hot Springs Fork, as I do for every one of your WyEast documentaries.

Your productions are a big undertaking. That you do all of it so well and appealingly really adds to the enjoyment and learning, and the appreciation of many.

Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person