Part 1 of this article introduced the idea of restoring the surviving sections of the old Mount Hood Loop Highway to become part of a world-class cycle tour along this historic route. Part 2 focuses on these surviving historic sections of the old road, from Zigzag on the west side of the mountain to the Sherwood Campground on the east side, and how to bring this vision to reality.

________________

THE CONCEPT

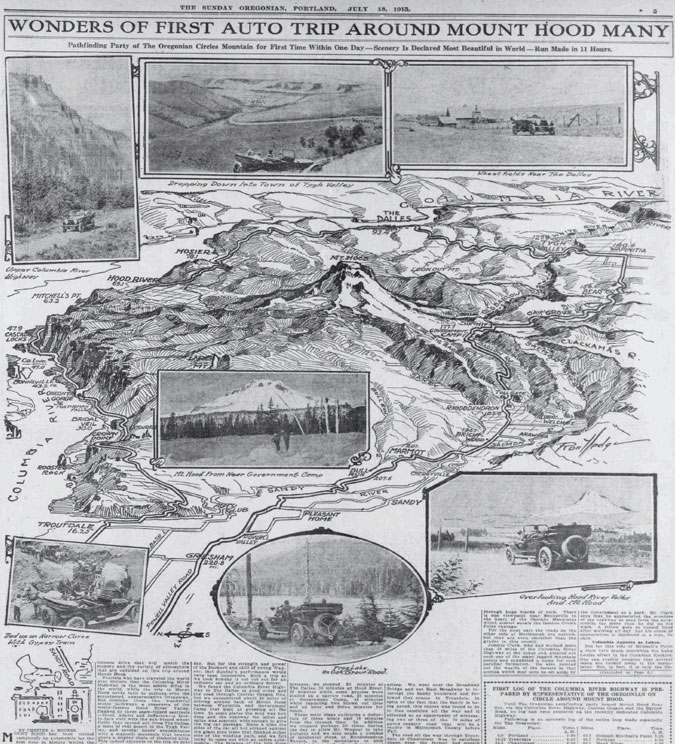

In the near-century since the original Mount Hood Loop was completed in early 1920s, the old route has gradually been replaced with straighter, faster “modern” highways. In areas outside Mount Hood National Forest, the bypassed sections of the old road are mostly still in use, often serving as local roads. But inside the national forest, from Zigzag to Sherwood Campground, long sections of the old road were simply abandoned, left to revert to nature when new, modern roads were built in the 1950s and 60s. Some bypassed sections are still in use, though mostly forgotten.

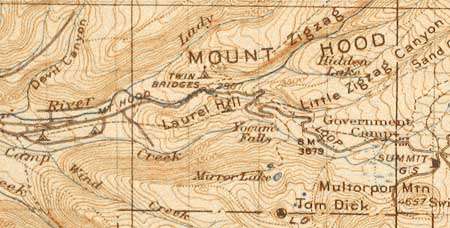

This is 1930s-era map (below) shows the original alignment of the Mount Hood Loop highway in red and the approximate location of the modern highway alignments of US 26 and OR 35 superimposed in black:

[click here for a large version of this map]

The concept of reconnecting these forgotten sections of historic road is straightforward, building on the example of the Historic Columbia River Highway (HCRH) in the Columbia Gorge. As in the Gorge, places where modern highways on Mount Hood simply abandoned or bypassed the old route, the surviving segments of the old road would be the historic building blocks for creating a new “state trail”, which is simply a paved bicycle and pedestrian path closed to automobiles.

Sections where the historic route was completely destroyed by modern highways would be reconnected with new trail, like we see in the Gorge, or with protected shoulder lanes on quiet sections of the modern highway in a couple areas.

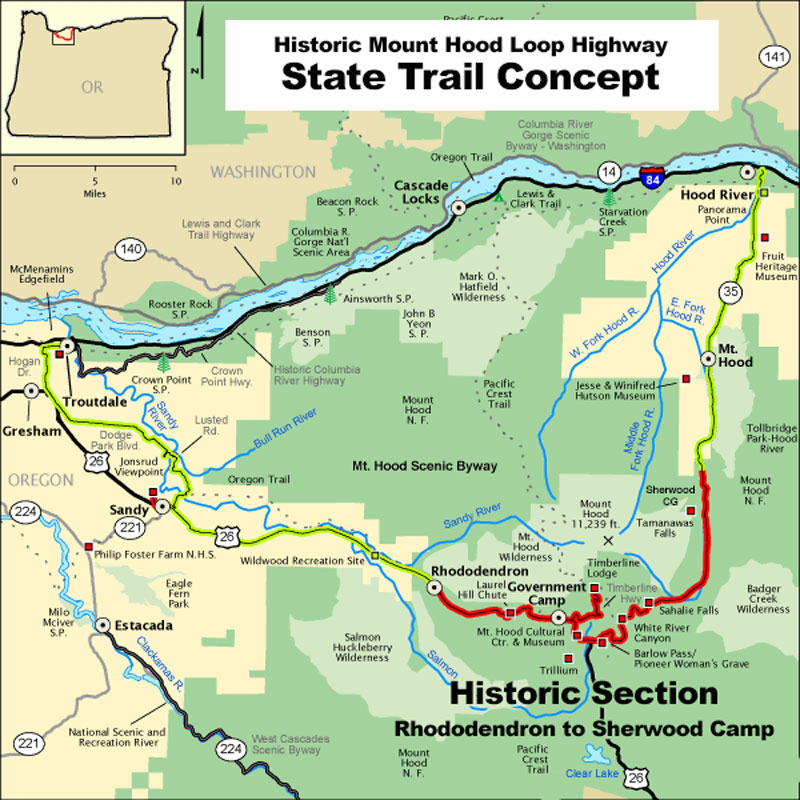

This map shows the overall concept for restoring the route as the Historic Mount Hood Loop State Trail:

[click here for the 11×17″ JPG version]

[click here for the 11×17″ PDF version]

Segments shown in blue on the concept map are where bypassed sections of the old highway still survive and segments shown in red are where new trails would connect the surviving historic segments. All of the new trail sections are proposed to follow existing forest roads to minimize costs and impacts on the forest.

The concept map also shows several trailheads along the route where visitors would not only use to access the trail, but would also have trail information and toilets. These trailheads already exist in most cases, with several functioning as winter SnoParks that could be used year-round as part of the new trail concept.

Six Forest Service campgrounds (Tollgate, Camp Creek, Still Creek, Trillium Lake, Robinhood and Sherwood) already exist along the proposed route and two long-forgotten campgrounds (Twin Bridges and Hood River Meadows) are still intact and could easily be reopened as bikepacking-only destinations.

EXPLORING THE ROUTE

The next part of this article explores the scenic and historic highlights of the historic highway in three sections, from Rhododendron on the west side of the mountain to the Sherwood Campground and East Fork Hood River on the east side.

West Section – Rhododendron to Government Camp

Beginning at the tiny mountain community of Zigzag, it’s possible to follow a couple bypassed segments of the old loop highway, notably along Faubion Road, but most of this section would follow a new, protected path on US 26 to Rhododendron, where the off-high trail concept begins.

Part 1 of this article outlined the economic benefits of cycle touring, and by anchoring the west end of the new trail in Rhododendron, this small community would benefit from tourism in a way that speeding winter ski traffic simply doesn’t offer. The gateway trailhead would be located at the east end of Rhododendron, connecting to the Tollgate Campground, the first camping opportunity along the proposed route

From Tollgate, the new route would follow the Pioneer Bridle Trail for the next two miles to the Kiwanis Camp Road junction, on US 26. This is a lightly used section of the Pioneer Bridle Trail, which was built by the Civilian Conservation Corps from Tollgate to Government Camp in the 1930s. This part of the corridor follows the relatively flat valley floor of the Zigzag River, so there is plenty of room for a new trail to run parallel to the Pioneer Bridle Trail, as another option.

Once at the Kiwanis Camp Road junction, the new route would share this quiet forest road for the next next couple miles. Kiwanis Camp Road is actually a renamed, surviving section of the old highway and still provides access to the Paradise Park and Hidden Lake trails into the Mount Hood Wilderness.

Along the way, this section of old highway passes the site of the long-abandoned Twin Bridges campground, where a surviving bridge also forms the trailhead for the Paradise Park Trail. This shady old campground is quite beautiful, with the rushing Zigzag River passing through it. It could easily be reopened as a bikepacking-only camping spot along the tour.

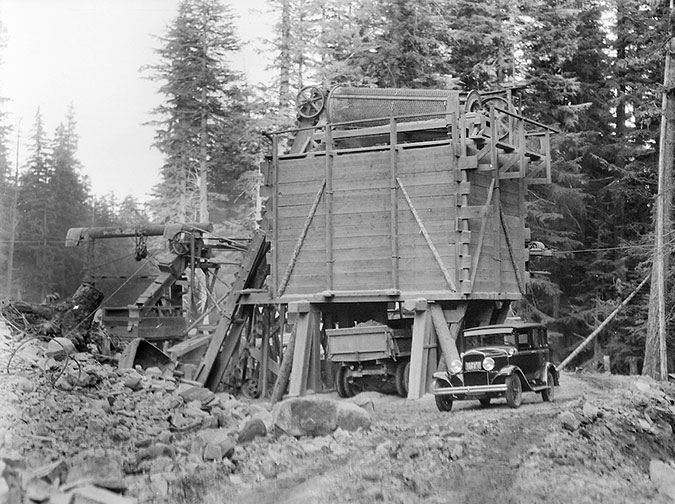

This operating section of old highway soon ends at the Little Zigzag River and the short spur trail to pretty Little Zigzag Falls. The enormous turnaround here once served as a rock quarry for the original loop highway, and has plenty of room serve as trailhead for the new state trail

From here, the old road begins an ascent of Laurel Hill, one of the most scenic and fascinating sections of the old highway. Large boulders now block the old highway at the historic bridge that crosses the Little Zigzag River, and from there, an abandoned section of the old road begins the traverse of Laurel Hill.

This abandoned section of historic road crosses the upper portion of the Pioneer Bridle Trail where an unusual horse tunnel was constructed under the old highway as part of creating the Bridle Trail. It’s hard to imagine enough highway traffic in the 1930s to warrant this structure, but perhaps the trail builders were concerned about speeding Model As surprising visitors crossing the road on horseback? Whatever the reason, the stone bridge/tunnel structure is one of the many surviving gems hidden along the old highway corridor.

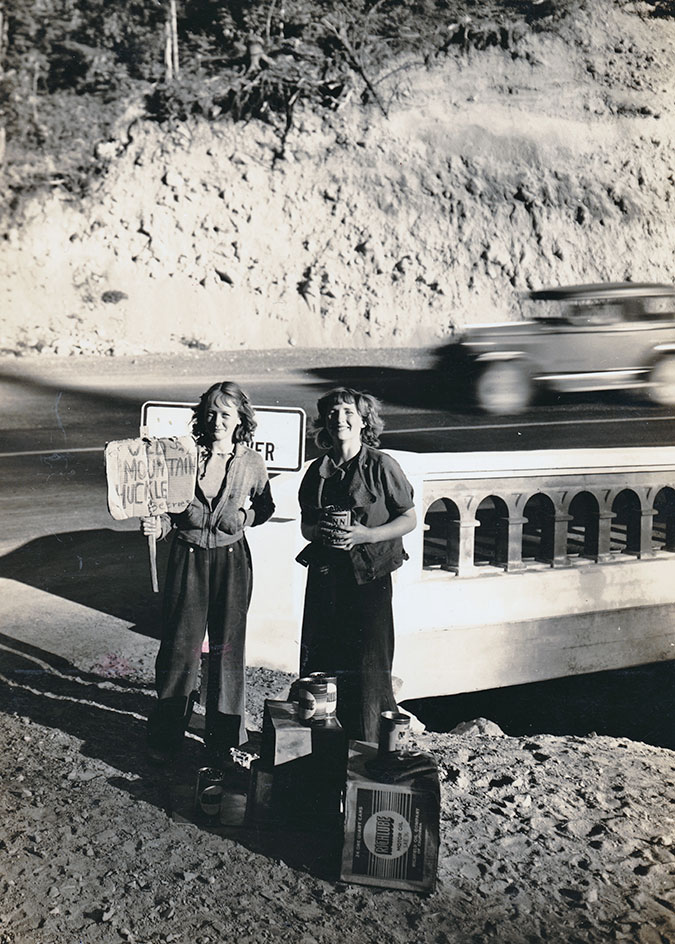

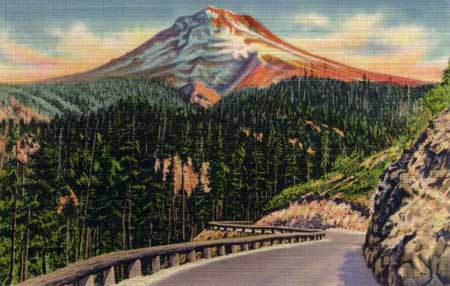

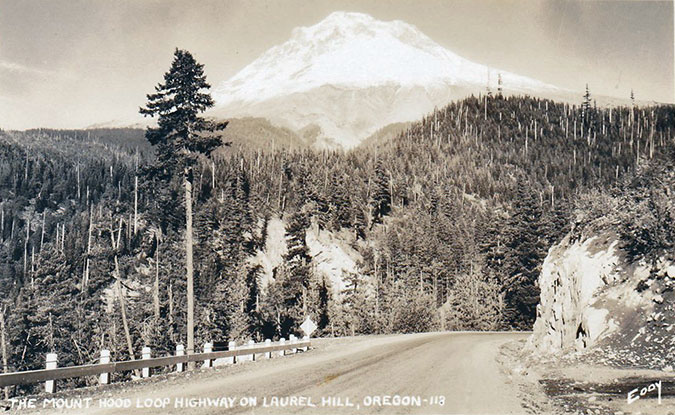

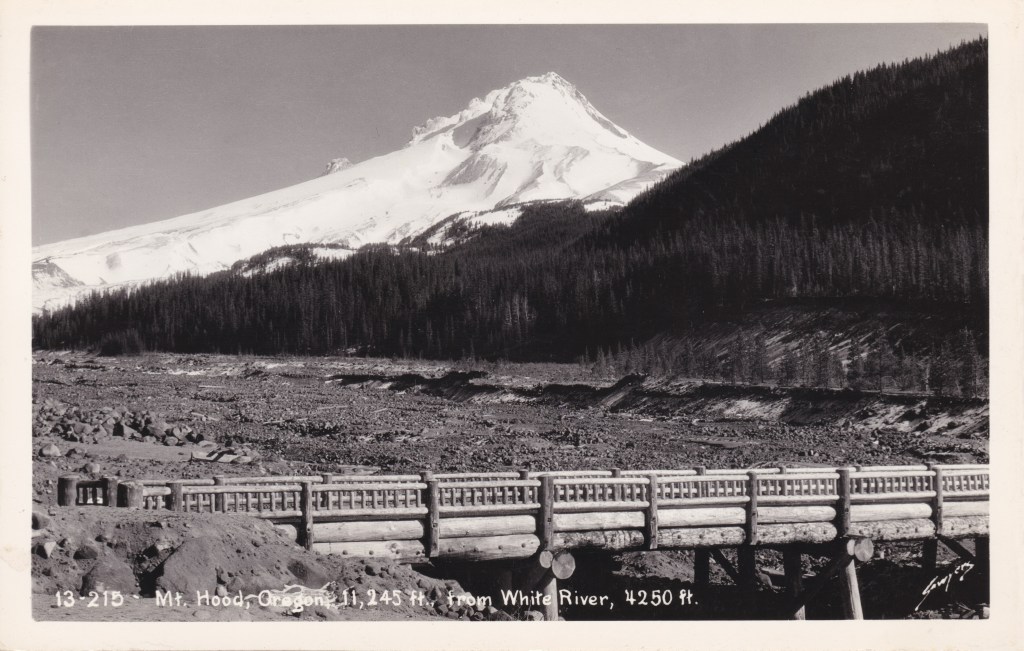

From the Pioneer Bridle tunnel overcrossing, the old road soon dead-ends at a tall embankment, where modern US 26 cuts across the historic route. The spot where the modern highway was built was once one of the most photographed waysides along the old highway, appearing in dozens of postcards and travel brochures. It was the first good view of the mountain from the old highway as it ascended from the floor of the Zigzag Valley to Government Camp (below).

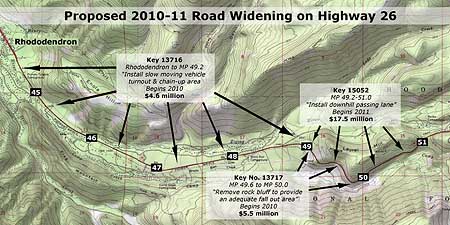

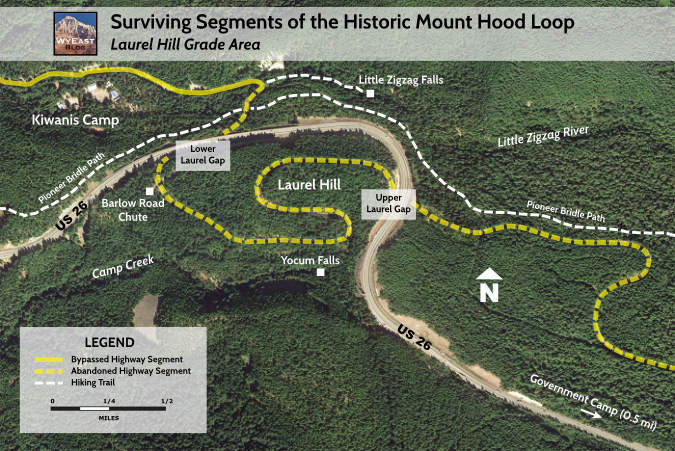

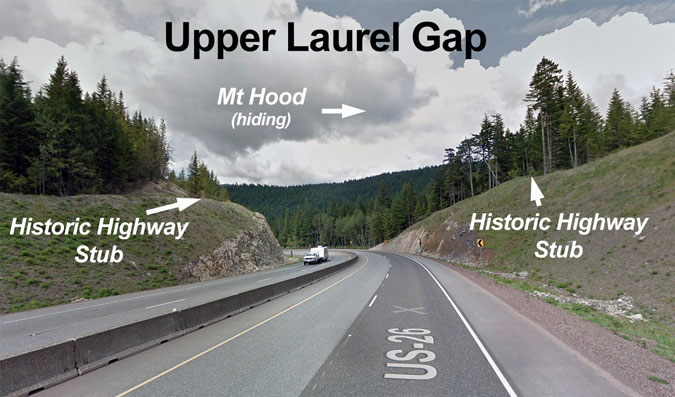

Although almost all of the old highway survives where it climbs the Laurel Hill grade, this spot marks one of the two major gaps along the way that would require a significant new structure to reconnect the route. A second gap occurs at the crest of Laurel Hill, to the east, where the modern highway cuts deeply through the mountain. This map shows the surviving, abandoned sections of the historic highway along the Laurel Hill grade and upper and lower gaps that must be bridged:

[click here for a large version of this map]

On the ground, the lower Laurel Hill gap looks like this:

The lower Laurel Hill gap is at a well-known spot where a history marker points toward a short trail to one of the Barlow Road “chutes” that white migrants on the Oregon Trail endured in their final push to the Willamette Valley.

ODOT has made this section of highway much faster and more freeway-like in recent years in the name of “safety”, but in the process made it impossible for hikers to cross the highway from the Pioneer Bridge Trail to visit the Barlow Road chute. A freeway-style median now blocks anyone from simply walking across the highway and cyclone fences have been added to the north side to make sure hikers get the message.

Given this reality, both of the Laurel Hill gaps would be great candidates for major new crossings, along the lines of work ODOT has done in the Gorge to reconnect the HCRH. This viaduct (below) was recently built by ODOT at Summit Creek, on the east side of Shellrock Mountain, where the modern I-84 alignment similarly took a bite out of an inclined section of the old highway, leaving a 40-foot drop-off where the old road once contoured downhill. This sort of solution could work at the lower Laurel Hill gap, too.

Beyond the Laurel Hill history marker on the south side of the modern US 26, a set of 1950s stone steps (below) leads occasional visitors up to the next section of abandoned Mount Hood Loop highway, where the old route continues its steady climb of Laurel Hill.

This section of the abandoned route is in remarkably good shape, despite more than 60 years of no maintenance, whatsoever. It also briefly serves as the trail to a viewpoint of the Barlow Road chute — a footpath to the top of the chute resumes on the opposite side of the old highway, about 100 yards from the stone steps.

When the historic highway was built in the 1920s, the Barlow Road was still clearly visible and only a few decades old. Despite the care they used elsewhere to build the scenic new road in concert with the landscape, there was no care given to preserving the old Barlow Road. Thus, the historic highway cut directly across the chute, permanently removing a piece of Oregon history.

Today, the footpath to the top of the chute still gives a good sense of just how daunting this part of the journey was (below). This short spur trail, and others like it along the surviving sections of the old highway, would be integrated into the restored Mount Hood Loop route, providing side attractions for cyclists and hikers to explore along the way.

Beyond the Barlow chute, the old highway enters a very lush section of forest, where foot traffic from explorers continues to keep a section of old pavement bare (below). Scratch the surface, and even under this much understory, the old highway continues to be in very good condition and could easily be restored in the same way old sections of highway in the Gorge have been brought back to life as a trail.

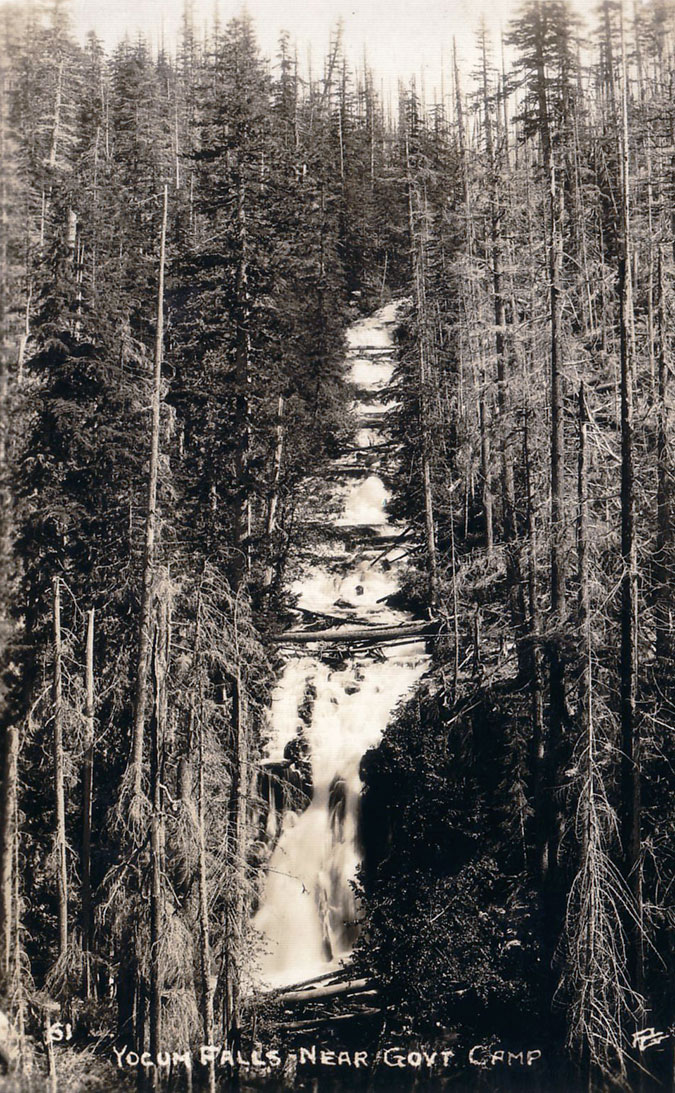

Some of the foot traffic along the abandoned Laurel Hill section of the old loop road is headed toward a little-known user path that drops steeply down to Yocum Falls, on Camp Creek. This is a lovely spot that deserves a proper trail someday, and would make an excellent family destination, much as the Little Zigzag Falls trail is today.

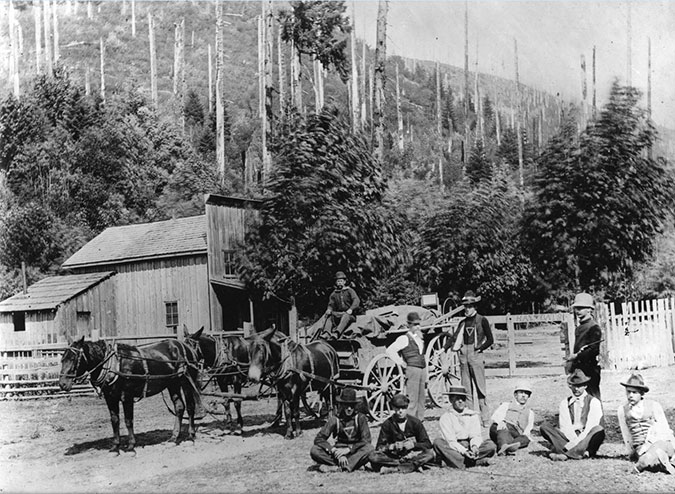

Yocum Falls was once well known, as the full extent of this multi-tiered cascade could be seen from along the old highway. As this old postcard from the 1920s shows (below), Camp Creek also served as a fire break for the Sherar Burn, which encompassed much of the area south of today’s US 26 in the early 1900s. You can see burned forest on the south (right) side in this photo and surviving forest on the north (left) side:

The fire also created this temporary view of the falls in the early 1900s, but the forest has since recovered and obscured the view. Today, the short hike down to the falls on the user path is required for a front-row view of Yocum Falls.

Beyond the falls, the abandoned highway makes a pronounced switchback and begins a traverse toward the crest of Laurel Hill. Here, the vegetation becomes more open, and road surface more visible (below).

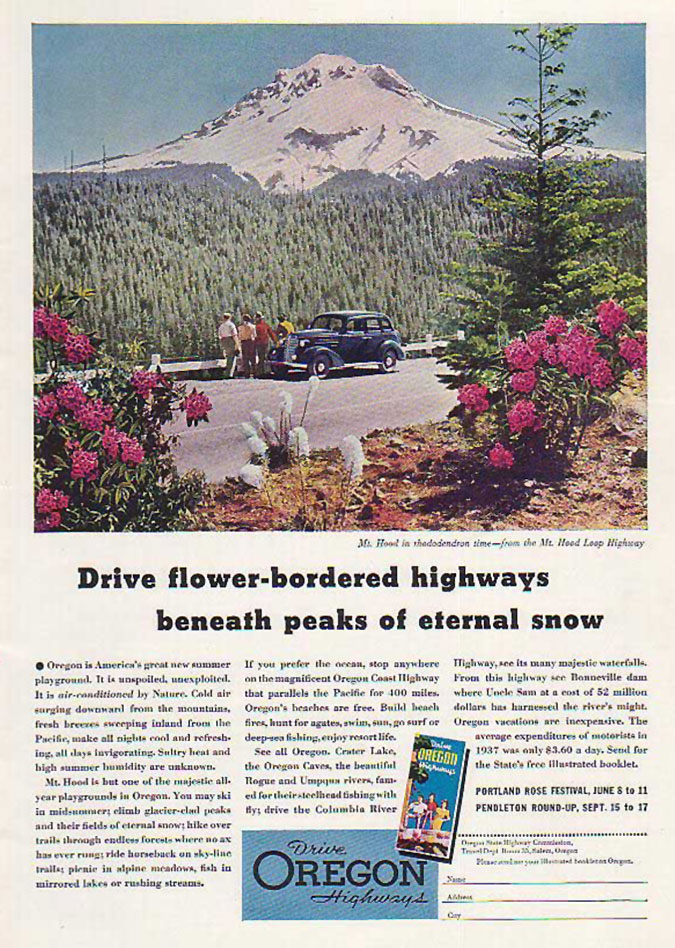

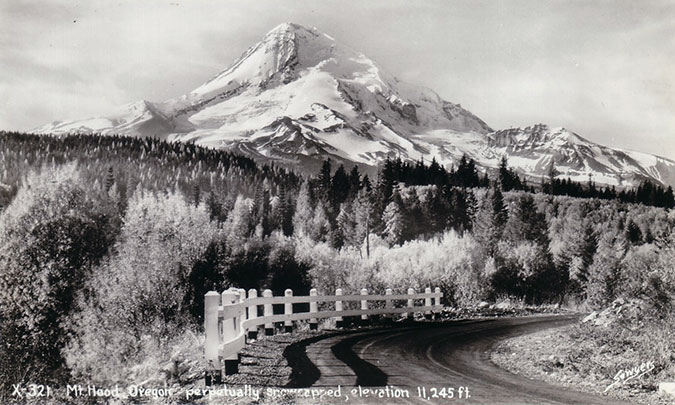

Soon this abandoned section of old road makes another turn, this time onto the crest of Laurel Hill. When the historic highway was built, this stretch was still recovering from the Sherar Burn, and the summit was dense with rhododendron and beargrass that put on an annual flower show each June. This was perhaps the most iconic stop along the old route, appearing on countless postcards, calendars and print ads (below).

Today, most of this section has reforested, but there are still views of the mountain and opportunities for new viewpoints that could match what those Model A drivers experienced in the early days of touring on Mount Hood.

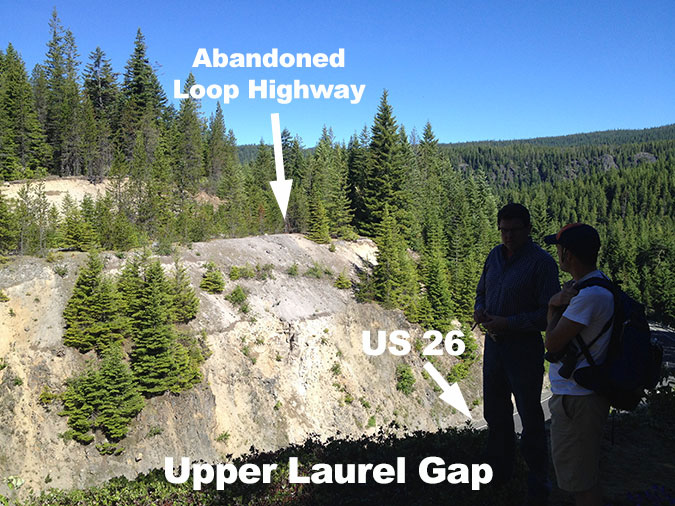

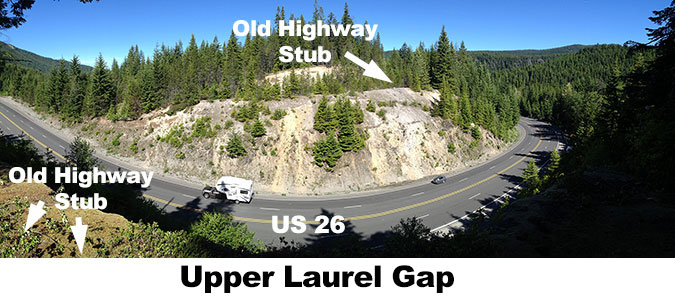

Soon, this abandoned section of old road on Laurel Hill reaches the upper gap, where ODOT has recently made the yawning cut through the crest of the hill even wider. This schematic is a view of the cut looking north (toward the mountain), with the stubs of the historic highway shown:

If there is any good news here, it is that the modern highway cut is perpendicular to the old loop highway, making it possible to directly connect the surviving sections of the old road with a new bridge. This view (below) is from the eastern stub of the old route, where it suddenly arrives at the modern highway cut. The stub on west side of the cut is plainly visible across US 26:

This panoramic view (below) from the same spot gives a better sense of the gap and the opportunity to bride the upper Laurel Hill gap as part of restoring the old route as a trail. A bonus of bridging the upper gap would be an exceptional view of Mount Hood, which fills the northern skyline from here.

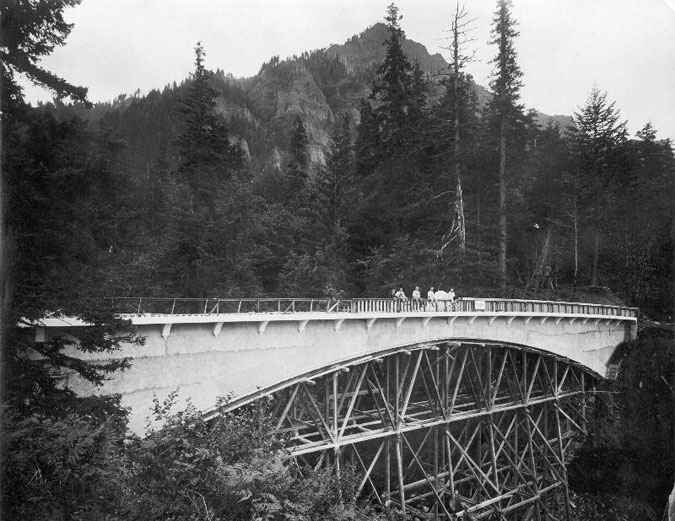

The upper gap is about 250 feet across and 40 feet deep, so are there any local examples of a bridge that could span this? One historic example is the old Moffett Creek Bridge on the HCRH, pictured below while it was being constructed in 1916. This bridge measures about 200 feet in length with a single arch.

The City of Portland recently broke ground on the new Earl Blumenauer Bridge, a bicycle and pedestrian crossing over Sullivan’s Gulch (and I-84) in Portland. This very modern design (below) might not be the best look for restoring a historic route on Mount Hood, but at 475 feet in length, this $13.7 million structure does give a sense of what it would take to span the upper gap at Laurel Hill.

That sounds like a big price tag, but consider that ODOT recently spent three times that amountsimply to add a lane and build a concrete median on the Laurel Hill section of US 26. It’s more about priorities and a vision for restoring the old road than available highway funding. More about that in a moment.

Moving east from the upper Laurel Hill gap, the abandoned section of the old highway continues (below) toward Government Camp, eventually reaching the Glacier View trailhead, where the surviving old highway now serves as the access road to this popular, but cramped, SnoPark.

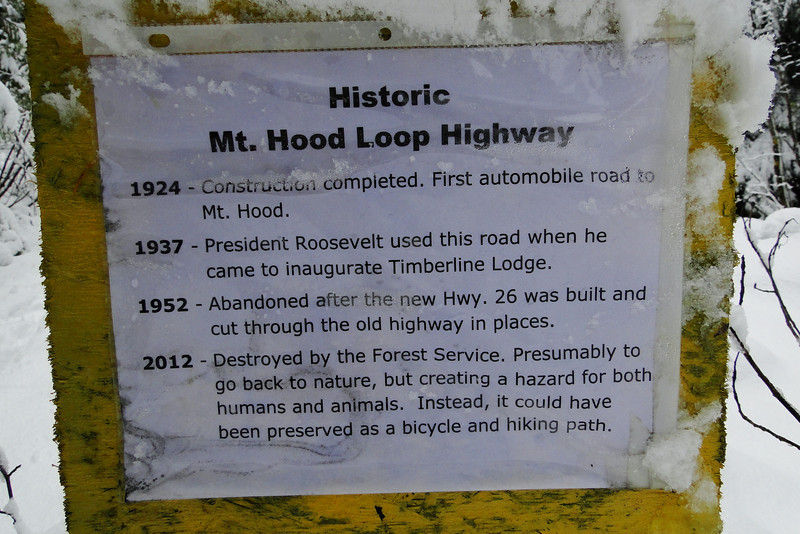

Sadly, the Forest Service recently destroyed a portion of the abandoned loop highway just west of the Glacier View trailhead, leaving heaps of senselessly plowed-up pavement behind. While destroying this section of historic road was frustrating (and possibly illegal), it can still be restored fairly easily. But this regrettable episode was another reminder of the vulnerability of the old highway without a plan to preserve and restore it.

From the Glacier View trailhead, the old road become an operating roadway once again, curving south to another junction with US 26, across from the new Mirror Lake trailhead, where a major new recreation site completed in 2018. This trailhead provides parking, restrooms and interpretive displays for visitors to the popular Mirror Lake trail, and is immediately adjacent to the Mount Hood Ski Bowl resort and lodge.

Crossing the US 26 at this junction is a sketchy, scary experience, especially on foot or a bicycle. Fortunately, the 2014 Mount Hood Multimodal Plan, adopted jointly by the Forest Service and ODOT, calls for a major bicycle and pedestrian bridge here to allow for safe crossing by hikers, cyclists, skiers and snowshoers, so a plan is already in place to resolve this obstacle.

Middle Section – Government Camp to Barlow Pass

From the Mirror Lake trailhead, the old highway loops through today’s parking lot at the Mount Hood Ski Bowl resort, then crosses US 26 again to loop through the mountain village of Government Camp. These graceful curves in the old route were bisected when the modern US 26 was built in the 1950s, leaving them intact as local access roads. However, because the Government Camp section of the old road serves as the village main street, the concept for a Mount Hood Loop Highway State Trail parallels the south edge of US 26 along a proposed new trail section, and avoids two crossings of the modern highway in the process.

However, a more interesting (but complicated) option in this area is possible along the south edge of the Multorpor Fen, an intricate network of ponds, bogs and meadows sandwiched between the east and west Mount Hood Ski Bowl resort units. The remarkable view in the photo above shows one of the ponds along this alternate route, far enough from the modern highway to make traffic noise a distant hum. However, this route would also require crossing a section of private land at Ski Bowl East. The mountain views and buffer from the highway make this an option worth considering, nonetheless.

Both options are shown on the concept map at the top of this article, and either route through the Government Camp area leads to the northern foot of Multorpor Mountain, where the concept for the state trail is to repurpose a combination of existing and abandoned forest roads as new trail to historic Summit Meadow and popular Trillium Lake, where the second and third campgrounds along the proposed trail are located.

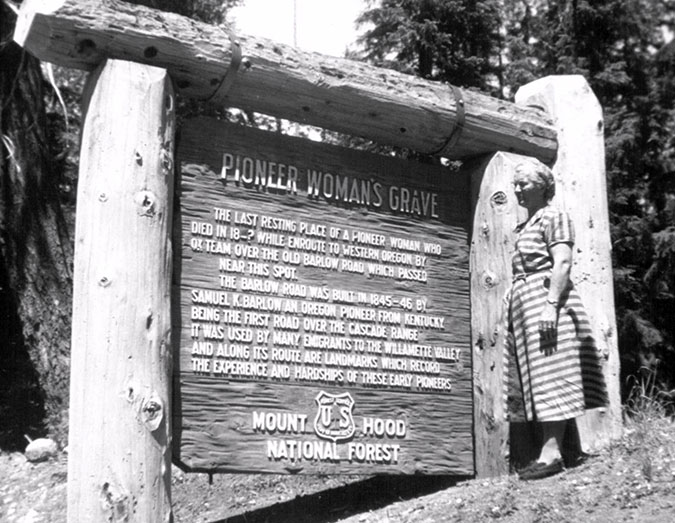

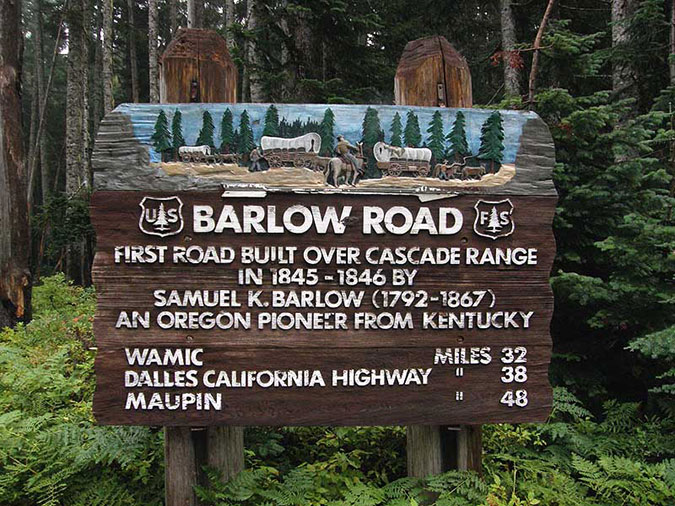

From Trillium Lake, the new trail would follow existing forest roads toward Red Top Meadow, to the east, then follow a new route for about a mile to the continuation of the historic loop highway, just east of the US 26/OR 35 junction. Here, a surviving section of the old road is maintained and remains open to the public, passing the mysterious Pioneer Woman’s Grave site as it climbs toward Barlow Pass.

When the original highway was completed in the 1920s, a viewpoint along this section of the road was called “Buzzard Point” and inspired postcards and calendar photos in its day. Few call this spot Buzzard Point anymore, but the view survives, along with a rustic roadside fountain built of native stone and still carrying spring water to the passing public. In winter, this section of the old road is also popular with skiers and snowshoers.

This section of the old route continues another mile or so to the large SnoPark at Barlow Pass, another important trailhead that serves both the loop highway corridor and the Pacific Crest Trail.

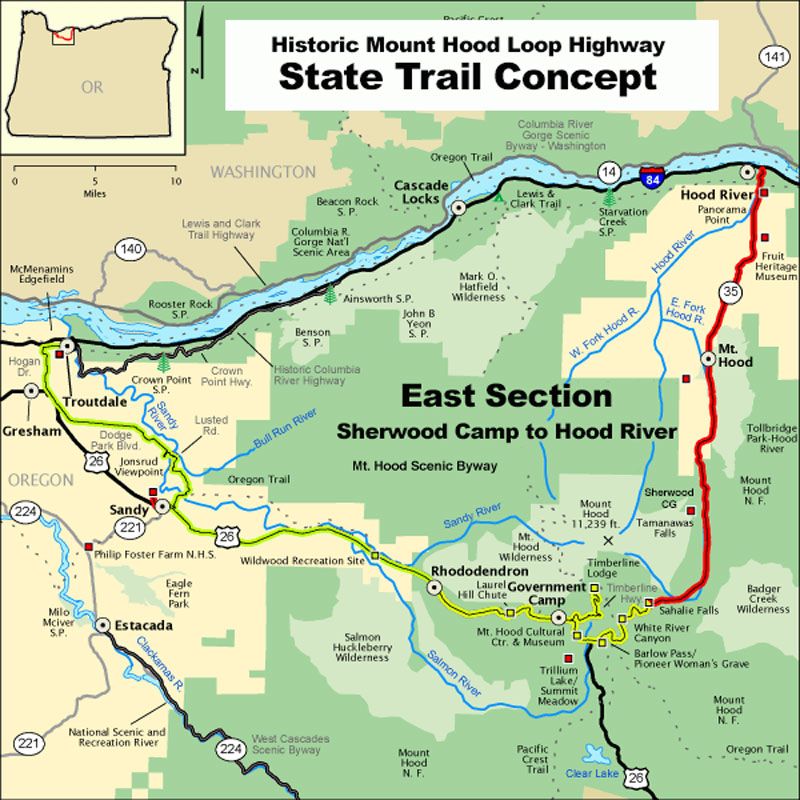

East Section – Barlow Pass to Sherwood Campground

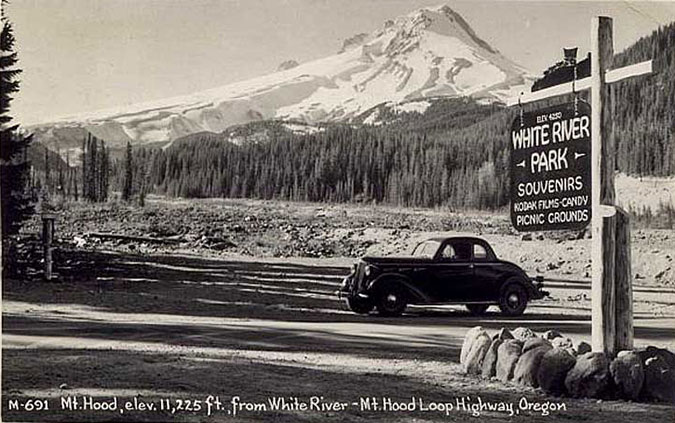

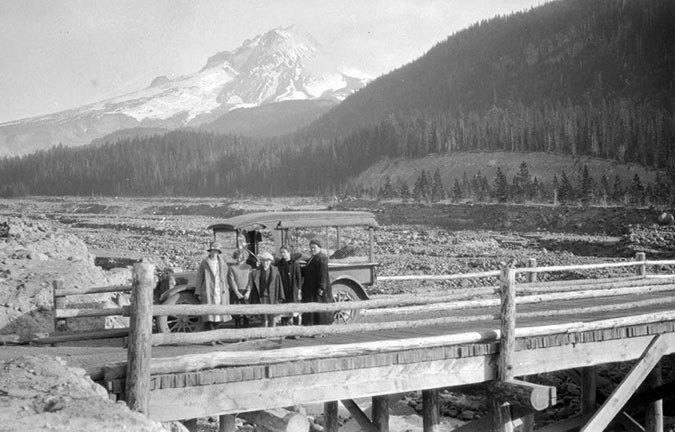

From Barlow Pass, the trail concept calls for a protected bikeway on the shoulder of OR 35, where it crosses the White River and climbs to Bennett Pass. It would be possible for the trail to take a different route along this section, but the traffic volumes and speed on OR 35 are much less intimidating than those on US 26, especially from spring through fall, when ski resort traffic all but disappears. There is also plenty of room to add protected bike lanes along this section of OR 35, including on the new bridge over the White River that was completed just a few years ago.

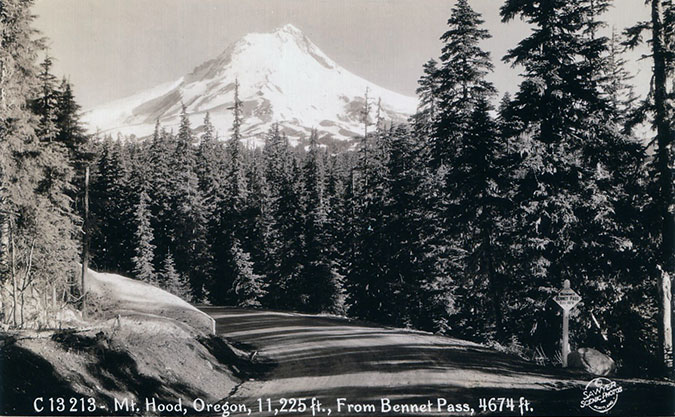

Upon reaching Bennett Pass, the proposed route would once again follow an especially scenic section of bypassed historic highway, with views of waterfalls, alpine meadows and the mountain towering above.

Of the many scenes along the old road that were postcard favorites, the view of the Sahalie Falls Bridge, stone fountain and falls in the background was among the most popular. The bridge was the largest structure on the original loop highway, and a scenic highlight (you can read more about the history of the bridge in this 2013 blog article “Restoring the Sahalie Falls Bridge”)

Today, the bridge is once again in excellent condition, having been restored by the Federal Highway Administration in 2013. For years, the bridge had been closed to automobiles because of its state of disrepair, but today it stands as perhaps the most significant historic highway feature along the old road.

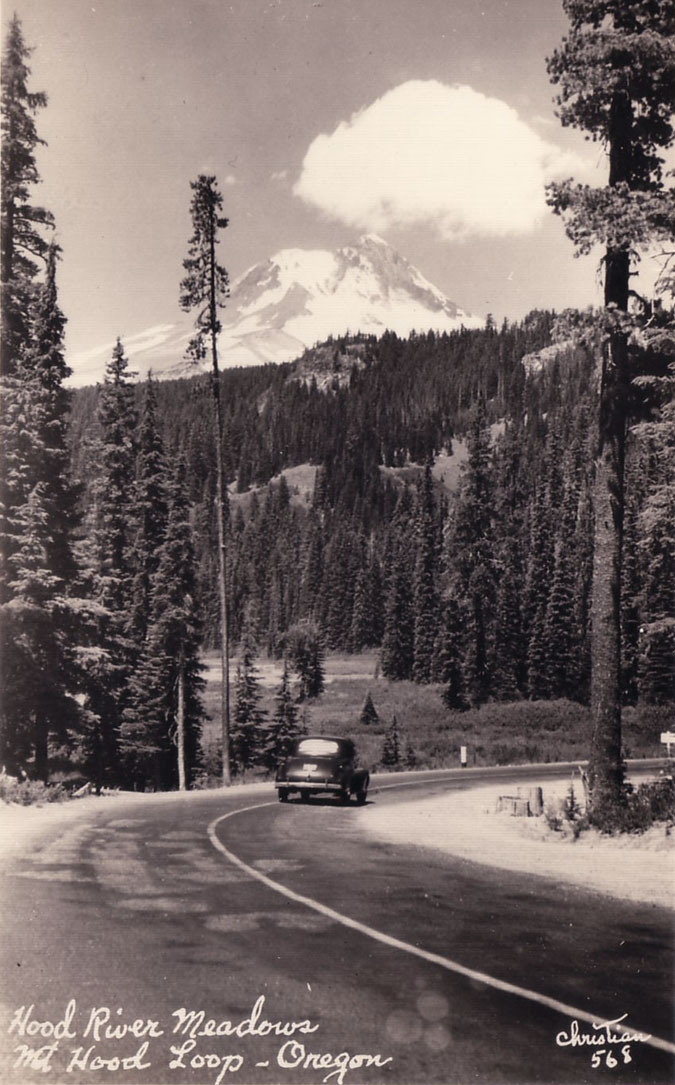

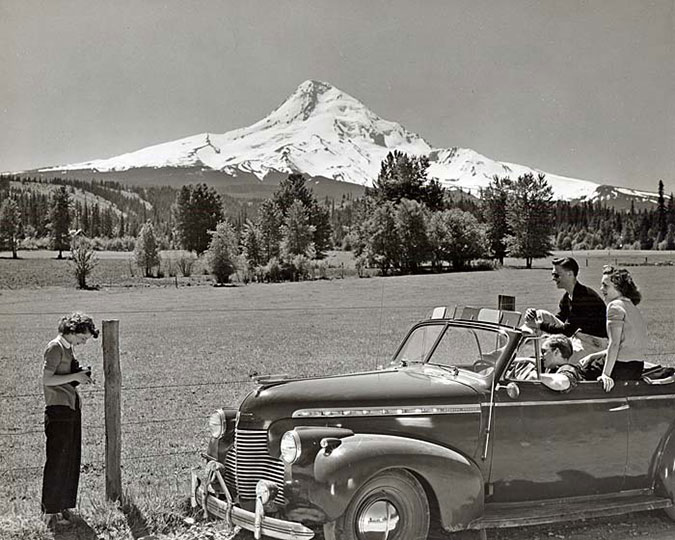

From Sahalie Falls, the historic road curves east through subalpine forests before arriving at Hood River Meadows, among the largest on Mount Hood and another spot that was featured in countless postcards and advertisements during the heyday of the old road.

The long-abandoned Hood River Meadows campground also survives here, along the east side of the meadows, and is still in excellent condition. This site could be reopened as a second bikepacking-only camping spot along the proposed trail.

Next, the historic road curves toward OR 35 where it also serves as the resort access road for the Hood River Meadows ski complex. From the spot where the old road meets OR 35, there are a couple more abandoned road sections along the north edge of OR 35 that could be reconnected as part of the Loop Highway trail concept, but this is the last of the surviving sections of the old road on this part of the mountain.

From here, the trail concept would connect a series of old forest roads on a gradual descent of the East Fork Hood River valley, toward Sherwood Campground, located along the East Fork, and completing the Mount Hood Loop Highway State Trail.

Sherwood Campground is a very old, still operating campground that includes another stone fountain from the old highway, located near the campground entrance. The campground is also a jumping off point for the popular trail to Tamanawas Falls. Nearby Little John SnoPark would serve as the main eastern trailhead for the new trail, with a short connecting route the main trail.

Sherwood Campground would form the eastern terminus of the historic section of the proposed Loop Highway State Trail. From here the larger Mount Hood scenic loop route would follow OR 35 through the narrowing canyon of the East Fork to the wide expanse of the upper Hood River Valley.

The canyon section along the East Fork is a crux segment for the loop route, with the modern highway wedged between the river and a wall of steep cliffs and talus slopes. Engineers designing a safe bikeway through this section of road could take some inspiration from the Shellrock Mountain in the Gorge, where the HCRH State Trail threads a similar corridor between I-84 and the talus slopes of Shellrock Mountain. This crux section along the East Fork is about a mile long.

WHERE TO START?

What would it take for this concept to become a reality? A crucial first step would be a feasibility study inspired by the HCRH State Trail, with an emphasis on the potential this example offers for restoring and reconnecting historic sections of the old Mount Hood Loop Highway on Mount Hood.

An obvious sponsor for this work would be the Oregon Department of Transportation, working in partnership with the U.S. Forest Service. These agencies have worked together to bring the Historic Columbia River Highway State Trail to reality and have both the experience and capacity to repeat this success story on Mount Hood. The following outline could be a starting point for their work:

Mount Hood Loop Highway State Trail Feasibility Study

Purpose Statement

Restore and reconnect surviving sections of the historic Mount Hood Loop Highway from Rhododendron to Sherwood Campground as a paved state trail the combines shared right-of-way and non-motorized trail experiences.

Feasibility Study Objectives

- Identify new, paved trail segments needed on public land to complete the loop using existing forest road alignments whenever possible.

- Identify surviving historic resources and new interpretive opportunities along the trail.

- Identify multimodal trailhead portals at the trail termini and at major destinations along the trail, including Rhododendron and Government Camp.

- Identify bike-and-hike opportunities that build on soft-trail access from a new, paved state trail.

- Coordinate and correlate route and design options and opportunities with the 2014 Mount Hood Multimodal Transportation Planand the Mount Hood Scenic Byway Interpretive Plan and Design Guidelines.

- Identify an alternate bicycle route for the Mount Hood Scenic Byway from Sandy to Rhododendron that does not follow the US 26 shoulder.

- Identify design solutions for designing a protected shoulder bikeway in the crux section of OR 35 in the East Fork canyon.

- Engage public and private stakeholders and the general public in developing the feasibility study.

But what would it really take..?

While ODOT has directly managed construction of the HCRH State Trail in the Gorge, a lesser-known federal agency has been taking the lead in recent, similar projects on Mount Hood. A little-known division of the Federal Highway Administration known as Federal Lands Highway is gaining a growing reputation for innovative, sustainable designs in recent projects on our federal public lands.

On Mount Hood, Federal Lands Highway oversaw the restoration of the Sahalie Falls Bridge in 2013, a long-overdue project that rescued this priceless structure from the brink of oblivion. Like any highway agency, they excelled at the roadway element of the project, like restoring the bridge and related structure. Other opportunities were missed, however, including improving the adjacent parking areas and providing interpretive amenities for visitors.

Federal Lands Highway also completed a major reconstruction of OR 35 at Newton Creek in 2012. This project was in response to massive flooding of this surprisingly powerful glacial stream in 2006. Their work here shows some of the negatives of a highway agency taking the lead, with a very large footprint on the land and a big visual impact with over-the-top, freeway-style “safety” features that are old-school by today’s design practices.

In 2012, Federal Lands Highway also completed (yet another!) bridge replacement over the White River, which was also damaged in the 2006 floods. The massive new bridge is similarly over-the-top to their work at Newton Creek, but Federal Lands Highway deserves credit for rustic design features that blend the structure with the surroundings, including native stone facing on the bridge abutments.

The most promising recent work on Mount Hood by Federal Lands Highway is the completion of the new Mirror Lake Trailhead in 2018. This project involved a significant planning effort in a complex location with multiple design alternatives. Their work here involved the public, too, something their earlier work at White River, Sahalie Falls and Newton Creek neglected.

The final result at Mirror Lake is an overall success, despite the controversy of moving the trailhead to begin with. The new trailhead is now a prototype of what other trailheads along a restored Mount Hood Loop Highway State Trailcould (and should) look like, complete with restrooms, interpretive signs, bicycle parking and accessibility for people using mobility devices.

Beyond the hardscape features at the new trailhead, Federal Lands Highways worked with the Forest Service to replant areas along a new paved section of trail. This work provides another useful template for how the two federal agencies could work together with ODOT in a larger restoration of the old Loop Highway as a new trail.

One of the compelling reason for Federal Lands Highway to take a leading role in a Loop Highway trail project is the unfortunate fact that ODOT has ceded the right-of-way for several of the abandoned sections of the old road to the Forest Service. This would make it difficult for ODOT to use state funds to restore these sections without a federal transportation partner like Federal Lands Highway helping to navigate these jurisdictional hurdles.

However, governance hurdles like this existed in the Gorge, too, and state and federal partners simply worked together to resolve them, provided they had a clear mandate to work toward.

Getting behind the idea… and creating a mandate

Bringing this trail concept to reality will take more than a feasibility study, of course — and even that small step will take some political lifting by local officials, cycling advocates, the local tourism community and even our congressional delegation. While the money is clearly there for ODOT to begin this work, it would only happen with enough political support to begin the work.

The good news is that Oregon’s congressional delegation is increasingly interested in outdoor recreation and our tourism economy, especially when where a coalition of advocates and local officials share a common vision. With the HCRH State Trail in the Gorge nearing completion after more than 30 years of dedicated effort by advocates and ODOT, it’s a good time to consider completing the old loop as the next logical step in restoring a part of our legacy.

Rumor has it that new legislation is in the works to ramp up protection and improve recreation opportunities for Mount Hood and the Gorge. Including theMount Hood Loop Highway State Trail concept in new legislation would be an excellent catalyst for moving this idea from dream to reality.

But could this really happen in today’s fraught political environment in Washington D.C.? Don’t rule it out: President Reagan was notorious for his hostility toward public lands, and yet he infamously “held his nose” and signed the Columbia River Gorge legislation into law in 1986, including the mandate to devise a plan to restore surviving sections of the HCRH as a trail.

So, could this happen in the era of Trump for Mount Hood? Stay tuned…