Licorice fern in their two favorite habitats – growing on moss-covered talus (foreground) and on the moss-covered trunks of a sprawling Bigleaf Maple in the Columbia River Gorge

One of the great heroes of our Pacific Northwest forests is so ubiquitous that it’s almost always hiding in plain sight. Licorice Fern (Polypodium glycyrrhiza) is a creeping fern species whose rhizomes cling to moss-covered surfaces – typically tree trunks and rocks. The many ferns around the world that belong to the Polypodium genus share the growth habit of sprouting fronds from creeping roots called rhizomes, reflecting the genus name Polypodium, which translates to “many footed”.

Licorice Fern on a grove of rainforest Bigleaf Maple and Red Alder along the Molalla River

While many of its cousins have especially furry “feet” to protect their rhizomes as they creep across bare surfaces, Licorice Fern has adapted to our rainforests by creeping under thick layers of moss. This not only protects their rhizomes, it also allows for more consistent access to moisture, given that these plants almost exclusively grow where there is no soil – just on rock surfaces or across tree bark.

Like their cousins, Licorice Fern still retain enough of these fine hairs and roots on their rhizomes to anchor themselves as they grow to the underlying rock or tree bark under that protective blanket of moss.

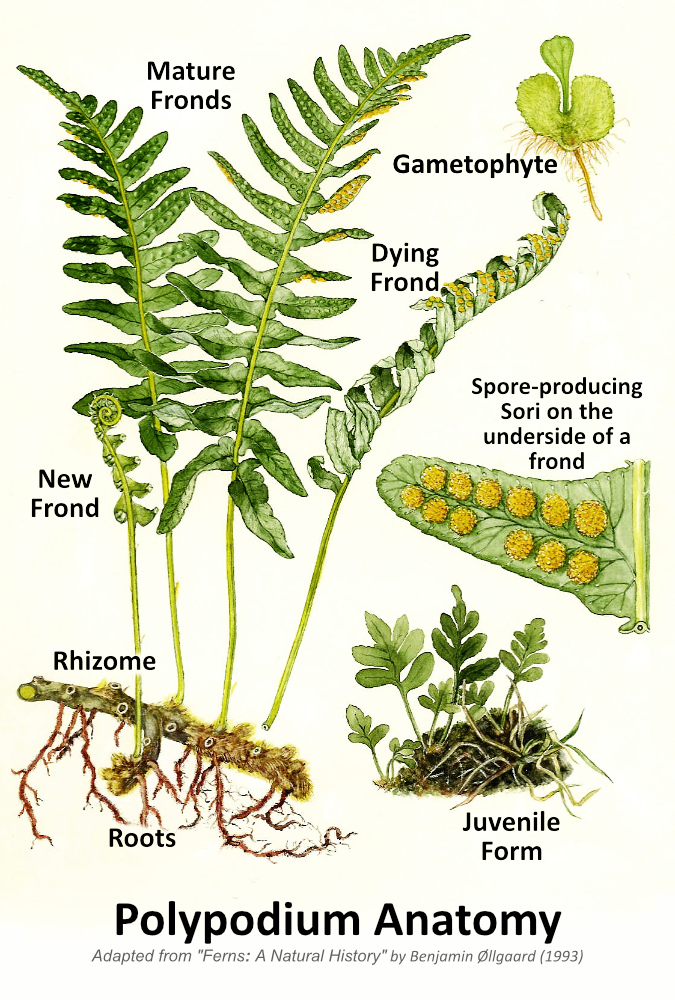

The anatomy and reproductive phases of a Licorice Fern

Licorice Fern have colonized these massive boulders along Moffett Creek where a layer of moss is enough for the ferns to take hold

The second part of their Latin name – glycyrrhiza – translates to “sweet root” and describes the licorice flavor of their rhizomes that give these ferns their common name. If you grew up in the forests of the Pacific Northwest, you probably learned as a kid to identify both Licorice Fern and Wild Ginger (another, less common plant with a strongly flavored underground stem) for their distinct flavors. Both are important first foods for indigenous people and continue to draw interest in the broader foraging community today.

Northwest indigenous peoples chewed Licorice Fern rhizomes for their flavor and as a medicine for colds and coughs, or cooked as a prepared food (which removes an enzyme in the rhizomes that can otherwise deplete Vitamin B). If you’re curious, you don’t have to destroy a Licorice Fern to sample its flavor (or better yet, to introduce kids to the plant). Carefully peel back the moss from the edge of patch of ferns to reveal the rhizomes and snap off a small piece to chew like gum.

A new colony of Licorice Fern is working its way up this very large Bigleaf Maple along the Molalla River

Their specialized adaptation to our moss-covered forests also explains their range. Licorice Fern are onlyfound in along the temperate Pacific Coast, from the Alaska Panhandle south to the Redwood forests of Northern California (an odd exception is a small population found in the Idaho panhandle). Within this narrow band, it is a remarkably adaptable species, in part because of its unusual growth cycle – more about that later in the article.

Their ability to grow without soil and cling to surfaces with their rhizomes makes Licorice Fern amazingly versatile and acrobatic in its native habitat. These ferns will happily grow upside down if there’s moss and moisture to be found on a cliff overhang, just as they can be found fifty feet (or more) from the forest floor, thriving on the trunk of an old-growth Bigleaf Maple or Red Alder, their most favored tree hosts.

Licorice Fern thrive where limbs come together on large trees like this Bigleaf Maple, where the moss is abundant and rainwater concentrates between storms

Fern heaven in a mixed rainforest of Bigleaf Maple, Red Alder and Western Redcedar near the Clackamas. Sword Fern carpet the forest flloor beneath the giant Bigleaf Maple on the left, while Licorice Fern scale its mossy limbs

Licorice ferns spread by both creeping with their “feet” and – like all ferns – by their spores. There is plenty of evidence of both forms of spreading and reproducing if you look closely in our forests.

When creeping by their feet, their progression up a tree trunk or across a moss-covered boulder is obvious. But when you see a smaller, isolated patch high up in a tree, or alone on a boulder, it is likely a new colony is forming from spores that took hold from a nearby parent colony.

Licorice Fern rhizome – tasty! (Wikipedia Commons)

Licorice Fern growing nearly 70 feet in the air on these Bigleaf Maples along Latourell Creek

This vertical rock face along Tanner Creek has only a thin layer of moss, but it faces north and is thus protected from summer heat, allowing several Licorice Fern to become established here

You’re not likely to notice Licorice Fern during its “gametophyte” phase – the transitional state in non-flowering plants that reproduce by spores by which a new fern is born. However, if you look closely where Licorice Fern grow, you might spot juvenile ferns that have recently emerged from the gametophyte phase with tiny, developing fronds.

Airborne spores allowed Licorice Fern to colonize this giant boulder in the middle of Silver Creek

The importance of their ability to reproduce by spores is on full display right now where our rainforests have recently experienced major wildfires – most notably, the Columbia River Gorge. Unlike many understory plants whose roots were protected from scorching heat by a layer of soil, Licorice Fern were decimated by the fires – along with the moss layers they anchor themselves in.

As the burned areas gradually recover in places like the Gorge, mosses are quickly beginning to take hold on talus slopes and burned trees. Licorice Ferns will soon follow as their spores find their way to moss layers that have grown sufficiently thick.

These cliff-dwelling Licorice Fern grow under a moist ledge on a north-facing cliff in the Gorge. This allowed them to escape the recent fire, and they will now send spores to the surrounding, burned area as it recovers from the burn

Licorice Fern spores are tiny and can travel long distances in the air, so one patch of surviving ferns in a burned area can quickly spread to form new fern colonies once the moss has returned and gametophytes can survive.

The scene below shows a talus slope in the Gorge that was covered with a thick blanket of moss and Licorice Fern before the 2017 Eagle Creek Fire, and now must rely on spores from survivors like this small colony to restore the fern population.

The small colony in the foreground somehow escaped the heat during the Gorge fire and now will help restore the much larger colony across this slope the moss recovery continues

One of the remarkable stories in the unfolding forest recovery after the fire is how pioneer species like Licorice Fern begin to move back to areas they once dominated. Before the fire, it would have been easy to simply see these plants are pretty additions to the mossy landscape.

Yet, in areas where the fire completely burned away the moss and fern layer on the talus slopes that define the Gorge, we now know the important role they play in helping hold these over-steepened slopes together. In places where moss and fern-covered talus had not moved for decades, the loss of this thin, living blanket has triggered countless rock slides that continue to plague trail restoration in the Gorge. In time, the moss and Licorice Fern partnership will once again return to these slopes and – barring another fire in the near term – help stabilize them, once again.

The unusual life cycle of a Licorice Fern

Licorice Fern in peak foliage… in mid-winter?

Licorice Fern are so familiar in our forests that most consider them to be perennial – like Sword Fern or Deer Fern – keeping their foliage year-round. And sometimes they are, but just as these plants can scale their foliage to local conditions, Licorice Fern are uniquely adapted to buck the conventional annual growth seasons that most plants follow, whereby new growth appears in spring and summer, followed by a dormant cycle in fall and winter.

I used to see Licorice Fern in late summer or fall looking yellowed and wilted, and assumed these plants were doing what a lot of broadleaf species do, and simply sacrificing some foliage in the face of our annual summer drought. This was based on seeing other Licorice Fern soldier through the dry spells where they were growing in more protected spots.

Licorice Fern fronds browning out in mid-summer in the Columbia River Gorge

Then I noticed something surprising on a late October visit to the Gorge several years ago: thousands tiny Licorice Fern fronds were unrolling from the moss layer on trees and rocks that had been rejuvenated by the first big rains and cooler temperatures of the fall season.

Researching this, I discovered that Licorice Fern often grow their annual burst of new foliage in the fall, not spring – and keep this foliage at least until the next summer drought, or until new fronds appear in the fall in places where they are more protected or have summer moisture.

Tiny new Licorice Fern fronds just beginning to emerge from drought-dormant rhizomes at Starvation Creek in mid-October

Young Licorice Fern fronds rising above the fall leaf litter near Starvation Creek in early November

Just one month into their re-emergence in late fall, this colony of Licorice Fern near Starvation Creek has produced a dense new flush of fronds that will mature to dark green and remain over winter and into the next summer drought

This upended growth cycle makes sense for a hardy fern that grows on the soil-less surfaces of trees and rocks, and thus more reliant on regular rainfall. Their thick rhizomes contain enough stored moisture to help them ride through short dry spells, but when long summer droughts hit our forests, these ferns have adapted to simply drop their foliage and go dormant until the rains reappear.

Their inverted growth calendar also explains why Licorice Fern favor deciduous host trees like Bigleaf Maple and Red Alder. Not only do these trees typically provide the thick moss layers that the ferns require, they lose their leaves in late fall and winter, when the ferns are growing and need access to light the most. While you will often see Licorice Fern in evergreen forests, their preferred environment is on deciduous trees or mossy rocks and logs in an open forest settings for this reason.

New Licorice Fern fronds emerging in fall from a moss-covered rock buried in new leaf debris – a common scene where these plants grow on rocks or logs in open forest

Licorice Fern also have the ability to scale their foliage to their microclimate, further expanding their adaptability. Plants in consistently cool, moist and shaded locations become quite lush, with fronds up to a foot long that persist year-round, even during summer droughts. This is why Licorice Fern appear as evergreens in rainforests on the wet west side of the Cascades.

This lush Licorice Fern colony in the Gorge grows at the protected base of a Bigleaf Maple and on adjacent moss-covered rocks – the best of both worlds for these ferns

In exposed locations where the moss layer is less thick, or they face extended summer droughts and very cold winters, Licorice Fern adapt by downsizing their foliage to minimize moisture loss and maximize the period in which they are leafed out each year. These locations include talus slopes and exposed cliffs throughout their range, or where they grow in shaded areas at the edge their range, east of the Cascades.

In these harsh environments they typically have short, rounded fronds, sometimes just an inch or two long, and often survive by shedding their downsized foliage in early summer and going dormant for the next 4-5 months.

The tiny new fronds on these licorice ferns are as large as they will get on this protected boulder in an Oregon White Oak grove in the otherwise arid east Columbia River Gorge

Their inverse growth cycle requires Licorice Fern to be especially hardy in winter, when tender new foliage is leafing out just as freezing temperatures arrive across most of their range. These plants are especially well-adapted to snow and ice, as can be seen every winter in the Columbia River Gorge, where winter weather conditions are especially severe. While a heavy snowfall or ice storm can level other ferns, Licorice Fern quickly bounce back and continue their upside-down growth cycle throughout winter.

Cliff-dwelling Licorice Fern typically downsize their foliage, both to preserve moisture in these exposed locations and to withstand tough winter weather conditions

Short, flexible fronds allow Licorice Fern to be completely buried in snow and ice, then emerge and spring back, ready to continue their winter growth cycle

Tiny-leafed Licorice Fern (center) with downsized leaves that reflect the harsh conditions of this talus slope rock garden near Gorton Creek in the Columbia River Gorge

While you’re not likely to spot a gametophyte, juvenile Licorice Fern are common and easy to spot, if you look closely. Their emerging fronds are the size of thumbnail and they lack rhizomes at this stage in their growth. They are often pioneers, as well – tiny patches growing far away from established colonies.

Juvenile Licorice ferns just beginning to emerge from moss on a talus slope boulder along Tanner Creek. The two arrows point to new fronds emerging from gametophytes. The brown Douglas Fir needles provide scale in this tiny scene

Well-developed juvenile fronds in this new colony of Licorice Fern along Tanner Creek will remain small for the first few years until these plants develop mature rhizomes under the moss layer

This young Licorice Fern has begun producing mature fronds – the wrinkles on the lower frond are from sori on its underside, where mature ferns produce their spores

Where do Licorice Fern get their nutrients when they typically do not grow in soil? The answer is that these plants are mycorrhizal, meaning they have a symbiotic relationship with fungus through their rhizomes and roots. In this relationship, the ferns use their green fronds to produce food through photosynthesis for the fungi, and in turn, the fungi provides minerals supplied from the substrate the plants are growing from. This is why it’s not unusual to find tiny Licorice Ferns growing from what sometimes seems to be solid rock.

Tiny fronds no more than two inches long help these cliff-dwelling Licorice Fern survive where they have sprouted from small cracks in the rock

While not much is known about other organisms that depend on the Licorice Fern, they are considered to be an important niche habitat for other species simply because they grow where most other plants are unable to, thus providing shelter and food for insects and other wildlife living within fern colonies.

While researching this article, I was especially curious to know if the unique, lowland Pika population in the Columbia River Gorge relies on Licorice Fern for food or nesting material, since these intrepid animals have uniquely adapted to live in talus slopes in the Gorge, and feed on the moss that covers these rocky slopes. Hopefully, as this unlikely Pika population continues to be studied, we’ll learn if it has also developed a special reliance on Licorice Fern, as well.

Urban Licorice Ferns..?

A bit weather-battered after the January ice storm, but bouncing back quickly

Thirty-two years ago, I constructed a stone retaining wall in my backyard and — wanting that “Gorge” look that I’ve always admired – I laid a patch of moss with a few Licorice Fern rhizomes embedded in it across some landscape rocks, just above the wall. For a couple years the ferns struggled to establish, but over the years they’ve formed a tough, lush colony that has now spread to cover much of the retaining wall.

When I took the above photo in late January, they had been battered by an ice storm, but were quickly bouncing back to winter form, and providing welcome patch of green in our extended gray, rainy season!

The author in 1981 (at age 19!) beginning my infatuation with licorice-ferns — and stone walls — at Wahkeena Falls

Because I lightly water these plants in summer, they remain green year-round, even in the middle of our typically hot, dry Portland summers. These urban ferns have thus adopted a growth cycle of June through April, dropping most of their previous year’s foliage (with occasional human assist) as warm weather arrives in mid-May, then vigorously rolling out new fronds by early June – apparently “aware” that I’ll be providing light watering over the summer months.

The real surprise came a few years ago when the now, well-established colony on the rock wall spread to their preferred habitat on a nearby Hollywood Juniper, of all places. There was just enough moss on the shaggy bark of this 30-year-old tree to host the ferns, and they also benefit from being shaded by the juniper’s evergreen foliage during our hot summers in Portland.

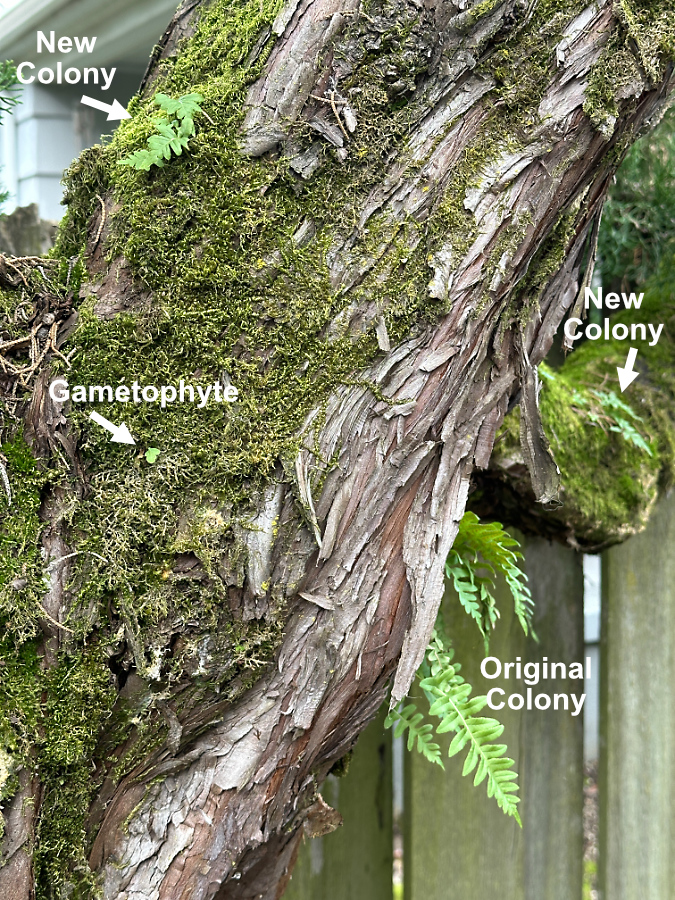

Pioneering Licorice Fern in my backyard… on a Hollywood Juniper!

Last year, the new colony on the juniper expanded to include two tiny new colonies, just above it, in this unlikely location. Their life here is exceptionally dry during the summer season – no supplemental water and at least three months of drought each year. The original colony even survived our unprecedented “heat dome” temperature of 116 F in June 2021! These new colonies have thus adopted to the conventional growth cycle of Licorice Fern, and go dormant in late summer, then re-emerge in the fall.

New colonies are now forming near the original Hollywood Juniper colony

The above photo shows the spreading Licorice Fern colonies on my backyard juniper tree – including a gametophyte just emerging from the moss layer. While I think the parent colony for these ferns was the most likely from the nearby rock wall, it turns out that if you look up when you pass under large, moss-bearing street trees throughout Portland, you’re likely to see Licorice Fern taking root throughout the urban area.

This century-old Norway Maple (below) on my block has several large colonies among its sprawling limbs, as does the 60-year-old Norway Maple growing in front of my house. These colonies are thriving in the middle of the city, even as TriMet buses and other urban traffic on this busy street passes directly below them.

Licorice Fern colonies leafing out in early November on a Norway Maple street tree near my home in North Portland

As our climate continues to warm, we can only watch and learn how native plants will (hopefully) adapt. A few years ago, I wouldn’t have included any ferns on a list of resilient adapters to climate change, but the ability of Licorice Ferns to maintain an inverted growth cycle, scale their foliage to harsh local conditions and go dormant when droughts arrive should help them manage the changes ahead.

Bringing the Forest Home…

In our time of climate change, native species that have already adapted to seasonal droughts are great options to consider for home gardens. They’re low-maintenance, bug and disease resistant and require little or no summer irrigation once they are established. But perhaps most importantly, they bring a slice of our amazing forests right into our yards for people and wildlife to enjoy year-round. If you can’t be in the forest, bring the forest to you!

Oregon Grape collected along a forest road near Mount Hood three years ago, and now bursting from its gallon pot (including through the drain holes!), ready to be planted in the garden

I’m a longtime forest transplanter, and licorice fern are just one of the dozens of native plants I’ve collected for my home garden over the years. Like many, I’ve also gradually transitioned away from ornamentals that require heavy watering, yet still fare poorly in our increasingly hot summers.

Among my favorite transplants are the many Sword Ferns planted throughout my garden. They provide year-round green and show a similar toughness to Licorice Fern. While they don’t share the ability to flip their growing seasons, Sword Ferns are able to scale the size of their fronds to local conditions and are remarkably drought tolerant, even in direct sun. I’ve also planted Oregon Grape (pictured above), Deer Fern, Salal and many Vine Maple (below) throughout the garden.

Vine maple leafing out just a few weeks after I collected it in the Clackamas River area three years ago. After two years in a planter, it developed a healthy root ball, and was able to go into the ground last spring

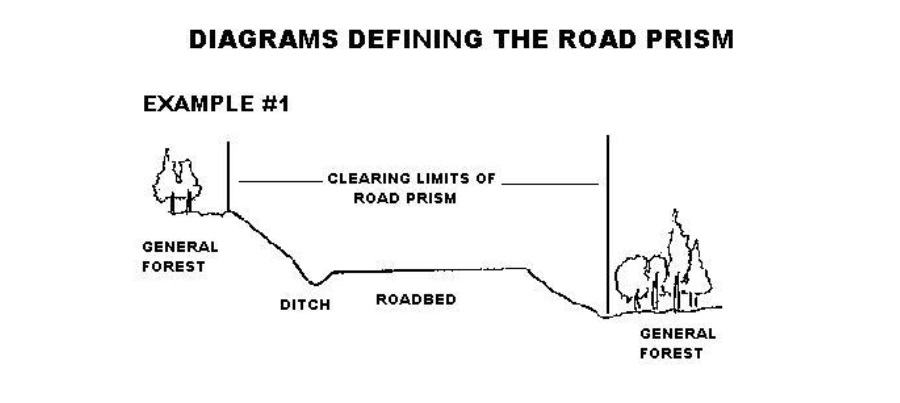

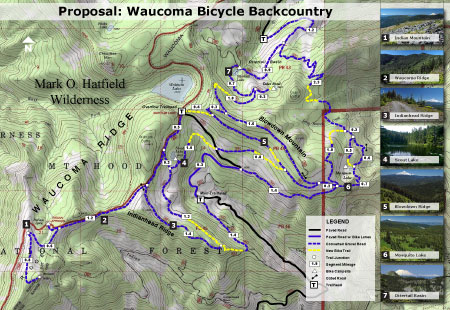

But is it legal to collect transplants on federal land? It is, though you are limited to what the Forest Service defines as the “road prism”. Generally translated, is the area along forest roads that was disturbed by construction, either for drainage or slope cuts. That includes embankments and ditches. The schematic is provided by the Forest Service:

No permit is required for non-commercial collecting. Having done this many times, I recommend digging in February or early March, just before plants emerge from winter dormancy. And don’t try to get a root ball in the normal gardening sense – forest plants have long, meandering roots that wrap around rocks and under logs, so you’re likely to end up with a “bare root” plant, even if you try to dig soil along with your transplant.

Instead, my system is to not fight this “bare root” reality, and instead, embrace it. A shovel, pair of loppers and some hand pruners are the essential tools needed. Also, pack a few large, plastic trash bags with balls of dampened newspaper inside to keep the roots on your mostly bare-root transplants moist for the drive home. Then, plant them in the ground or in pots as soon as you’re able to.

I like to grow my starts in containers with potting mix for a couple years to give them a chance to recover and develop a true root ball, then plant them in the yard in fall. That seems to speed up their adaptation to urban life significantly. Soon enough, they’ll asking for overpriced coffee and gluten-free mulch… 😊

You can learn more about collecting plants on Mount Hood ‘s forest roadsides here:

Harvesting Transplants on National Forest Land

______________

Tom Kloster | February 2024