The coming year marks the 16th annual scenic calendar that I’ve assembled for the Mount Hood National Park Campaign, with each calendar drawing from photos from the previous year of Mount Hood country. In the beginning, the proceeds helped defray the costs of the campaign website and (beginning in 2008) the WyEast Blog. But for the past several years, all proceeds have gone to Trailkeepers of Oregon (TKO), our premier trail stewards and advocates in Oregon (more on that toward the end of this article).

Looking back, the early calendars were more than a bit rough, especially given the clunky on-demand printing options in those early days of the internet and the emerging state of digital cameras, too! This is the “homey” inaugural cover that featured Elk Cove as it appeared way back in 2004:

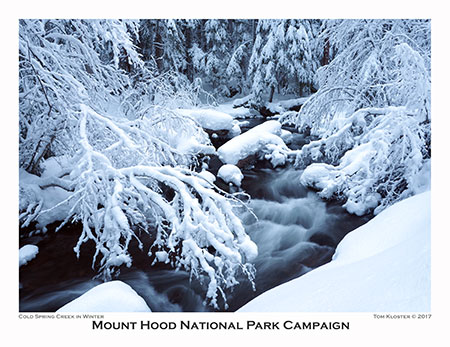

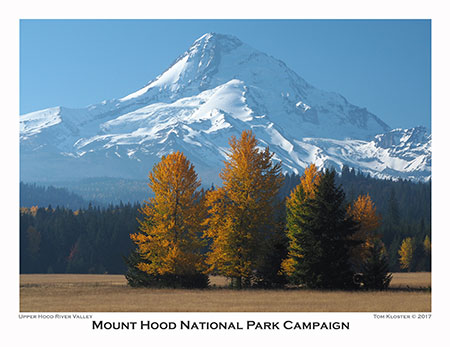

Over the years, the calendar has evolved, and on-demand printing quality has become downright exceptional. Each year I set aside my favorite photos over the course of the year, typically a few dozen by the time calendar season rolls around. Then the hard part begins: picking just 13 images to tell the story of Mount Hood and the Gorge. And as in years passed, this blog article tells a bit of the backstory behind images in the new calendar and includes a few photos that didn’t make the calendar.

________________

For 2020, the cover image is from a favorite spot on Middle Mountain, the rambling series of forested buttes that separate the upper and lower portions of the Hood River Valley. The sylvan view of Mount Hood from here is hard to match:

But the story of Middle Mountain is a bit less idyllic. Though most of the mountain is owned by Hood River County, the agency still hasn’t gotten the memo on modern, sustainable forestry and continues to aggressively log these public lands with old-school clearcuts.

This makes for low (or at least lower) taxes for Hood River County residents, but at the expense of future sustainability of the forest — which means future generations in Hood River are really paying the tab. This rather large clearcut (below) appeared this year, just east of the spot where the cover image for the calendar was captured, on a climate-vulnerable south-facing slope.

Will the forest recover here once again, as it always has before? Probably. But Pacific Northwest forest scientists are warning Oregonians not to take our low-elevation Douglas fir forests for granted, as they may not return, especially on hot south and west-facing slopes. Consider that just uphill from this spot some slopes on Middle Mountain are already too dry to support conifers, and are home to a few scattered Oregon white oak trees. Now would be a good time for Hood River County to adopt a longer view of its forests, and begin planning for more selective, sustainable harvests that don’t put the survival of their forests at risk.

For the January calendar image, I chose a close-up of the Sandy Headwall, which forms Mount Hood’s towering west face. This is a favorite spot for me after the first big snowfall of the year, when the mountain is suddenly transformed into a glowing white pyramid:

I have a little secret to share about this view, too. It turns out I’m not much of an “alpenglow” fan, which is downright sacrilegious for a photographer to admit! So, you’re unlikely to see one in the annual calendar. I just prefer the long shadows and shades of blue and ivory that light up in the hour beforesunset that are featured in the January image.

If you’re not familiar, alpenglow is that rosy cast that often appears at or just after sunset, and pictured on waytoo many postcards and calendars — at least for my taste! But my other little secret is that I still capture plenty of alpenglow photos, too. Who knows, maybe my tastes will change someday?

The following image didn’t make the calendar, but it shows the transformation from the above view that unfolded over the course of 30 minutes or as sun dropped over the horizon that cold, October evening:

February also features another snow scene, this time along the White River, when the stream nearly disappeared under ten feet of snow last winter:

But the White River photo came courtesy of an aborted snowshoe trip that day at nearby Pocket Creek. My plan was to hike up to a view of Mount Hood and Elk Mountain from the north slopes of Gunsight Ridge. I had made the trip about ten years ago and liked the sense of depth that having Elk Mountain in front of Mount Hood created from this angle. Instead, here’s what I found when I reached the viewpoint:

This isn’t the first viewpoint that has disappeared behind growing forests in my years of exploring Mount Hood, nor am I sad that the view went away. After all, this one came courtesy of a 1980s Forest Service clearcut, and while the view was nice, a recovered forest is even better. And besides, I still have this photo from 2009 to remind me of view that once existed here:

So, I returned to the trailhead that day and headed over to the White River for a short snowshoe trip in the evening light. While I picked a photo of the river and mountain for the calendar, there were some very pretty views unfolding behind me, too. These images capture the last rays of winter sun lighting up the crests of Bonney Butte and Barlow Butte. They may not be calendar-worthy, but are lovely scenes, nonetheless:

For the March calendar image, I picked a scene from Rowena Plateau, a spot famous for its spectacular displays of yellow Balsamroot and blue Lupine. The calendar view looks north across the Columbia River to the Washington community of Lyle, a town that nests seamlessly into the Gorge landscape, thanks in large part to the protections of the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area:

But the view behind me that day was pretty nice, too, though it didn’t make it into the calendar. This image (below) looks south toward McCall Point from the same vantage point, with still more drifts of wildflowers spreading across the terraced slopes:

For April, I chose a popular scene along the Old Salmon River Trail on Mount Hood’s southwest side just as the bright greens of spring were exploding in this rainforest. Here, a grove of 600-year old Western red cedar and Douglas fir somehow avoided several cycles of logging in the 1800s and 1900s to survive as the closest ancient forest to Portland:

How big is that Western red cedar on left? I’ve been asked that question a few times, and short of actually measuring it, I stepped in front of the camera to serve as a human yardstick (well, two yards, as I’m exactly six feet tall). Subtract a few inches for my hat, and I’d estimate the trunk to be about 15 feet across at the base and about 10 feet thick a bit further up.

What do you think?

One thing is for sure, we’re so fortunate that these old sentinels have survived to give us a glimpse into what many of our rainforest valleys used to look like.

Further down the trail, I also captured this scene (below) of a pair of leaning giants that mark the spot of an ancient nurse log, long since rotted away and revealing the roots that once anchored these trees to the nurse log when they were youngsters. Someday, they will fall and become nurse logs, too, repeating the rainforest cycle.

This unique pair of trees is easy to find if you’re exploring the Old Salmon River Trail. They’re located right along the river (below), at a scenic spot just off the trail where there are plenty of boulders for picnics and even a tiny beach in summer. It’s just beyond one of the rustic footbridges along the trail, and downstream from the ancient tree grove.

For May, I chose another photo from the Rowena Plateau, partly because it was such a good bloom this year, but also for the gnarled Oregon white oak that grows on this little knoll (below).

After exploring Rowena that day, I crossed the river and spent the evening over at Columbia Hills State Park, in Washington. While this sprawling preserve is certainly no secret these days, you can still count on it being pretty lonely once you hike into the vast meadows along the park’s trails.

This is the scene looking back toward The Dalles and Mount Hood as the sun dropped over the horizon on that lovely spring day:

For June, I selected an old standby, the understated but elegant Upper Butte Creek Falls (below), located in the Santiam State Forest. I visit Butte Creek at least twice each year, just because the area is so delightful, and also because it’s a showcase of what Oregon’s state forests could be.

The Oregon Department of Forestry has gradually expanded recreation opportunities throughout the state forest system over the past couple of decades, in recognition of growing demand for trails in our state. It’s an uphill battle, as state forests have generally been viewed by our state and local governments as a cash register, thanks to 1930s era laws that have traditionally been interpreted as promoting logging above all else.

Today, a group of Oregon counties are actually suing the state for “retroactive” payments based on this interpretation, though it’s an absurd and misguided case of robbing Peter to pay Paul. If successful, the “state” (that’s you and me) could pay over $1 billion to a handful of counties (possibly you, possibly me) to right this purported wrong. This power play further underscores the need to radically rethink how we manage our state forests in an era of climate change and changing values among the public.

While the area along the Butte Creek trail remains a verdant rainforest, it’s really just an island, with much of the surrounding public forest logged in the past, and planned for more logging. Adjacent private timberlands are faring even worse, with companies like Weyerhaeuser liquidating their holdings with massive clear cuts in the lower Butte Creek canyon.

The changing climate is starting to take its toll here, too. This view of Butte Creek Falls was taken on the same visit as the June calendar image, but as the photo shows, the creek is running at perhaps a third of its “normal” June flow after dry spring this year, with much of the falls already running dry. We’re learning that “normal” is no longer as drought years continue to become the new normal.

The warning signs of the changing climate are already showing up on the rocky viewpoint above Butte Creek Falls, where several Douglas fir (below) finally succumbed to the stress of summer droughts this year on the thin, exposed soils of this outcropping.

This is how climate change is beginning to make its mark throughout our forests, with trees growing in poor or thin soils lacking the groundwater moisture to make it through summer droughts. These trees are often further weakened and eventually killed by insects and diseases that attack drought-stressed forests.

The good news is that a new generation of forest scientists is sounding the alarm and as we’ve seen, a new generation of young people are made climate change their rallying cry. So, while we’re very late in taking action, I’m optimistic that Oregon will emerge as a leader in tackling climate change, starting with our magnificent forests.

For July, I chose another waterfall scene, this time in the sagebrush deserts east of Mount Hood, where the White River crashes over a string of three waterfalls on its way into the Deschutes River canyon (below).

Most people hike the paved trail into the rugged canyon, which begins an impressive, but partly obscured view of the dramatic upper falls. But few follow the fenced canyon rim upstream to this nice profile (below), just a short distance off the paved route. From here, the basalt buttes and mesas of Tygh Valley fill the horizon and remnants from the early 1900s power plant that once hummed here are visible on a side channel, below.

In 2011, I posted this article with a proposal for expanding tiny White River Falls State Park to save it from the kind of development it had just dodged at the time. Hopefully, we’ll eventually see White River Falls better protected and some of its history restored and preserved!

The August image in the new calendar is from my beloved Owl Point, a spot on the north side of Mount Hood that I visit several times each year as a volunteer for Trailkeepers of Oregon (TKO). In this view (below), evening shadows were starting to reach across the talus slopes below Owl Point, where low mats of purple Davidson’s penstemon painted the summer scene.

I was alone that day, scouting the trail for an upcoming TKO volunteer work party, so I had the luxury of spending a lot of time just watching the evening unfold through my camera. For photographers, clouds are always the unpredictable frosting that can make (or break) a photo, and the lovely wisps in the calendar image floated in from nowhere to frame the mountain while I sat soaking in the view.

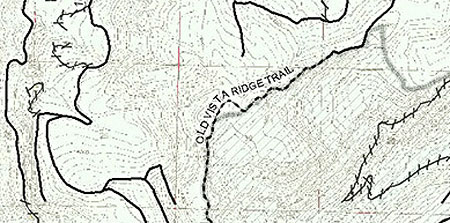

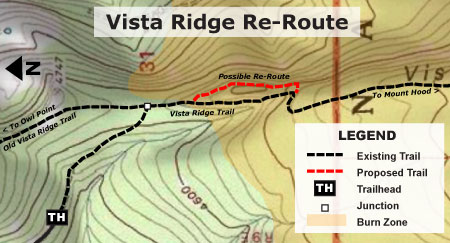

I joined a TKO trail crew the next weekend for our second year of “officially” caring for the Old Vista Ridge Trail to Owl Point since TKO formally adopted the trail from the Forest Service in 2018. We had a great turnout, with crews clearing several logs with crosscut saws and doing some major rock work (below) where TKO will be realigning a confusing switchback along the trail.

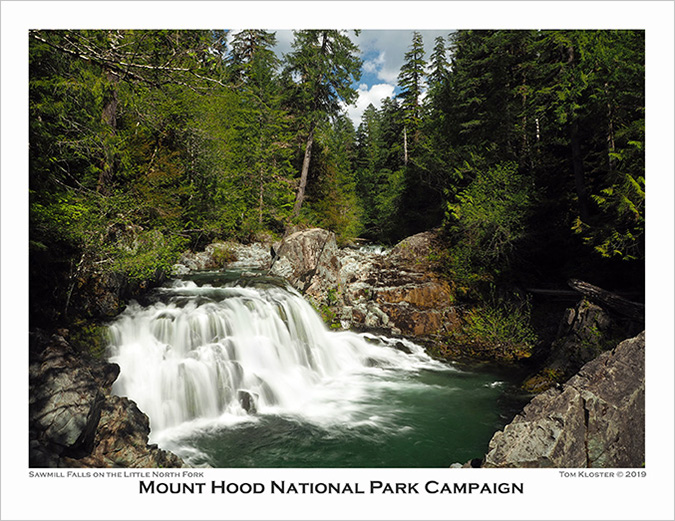

For September, something a little different for the calendar: Sawmill Falls on the Little North Fork of the Santiam River (below). This is a well-known spot on the Opal Creek trail, but the surprise is that I’d somehow never hiked this trail, despite growing up in Portland and having spent a lot of time exploring nearby Henline Creek over the past several years. But my explanation is fairly simple: this has been among the most notoriously crowded trails in Oregon for many years, and I’ve always just shied away.

Then my friend Jeff e-mailed to remind me that we were way overdue for a hike, and so we picked Opal Creek as one that neither of us had checked the box on before. It turned out to be a lovely day on a very pretty trail, and because we had picked a weekday, it was surprisingly quiet, too.

The photo of Sawmill Falls gives a better sense of the weather that day — lots of sun, and so this image is among a very few long-exposure waterfall scenes I’ve attempted in full sun. It’s also a blended image from three separate exposures, which is a lot of work to capture an scene! One benefit of shooting in the sun was the opportunity to include some puffy clouds and blue sky as a backdrop, making this a very “summery” image.

The conditions were more forgiving that day when we reached the bridge above Opal Pool, as a nice bank of clouds floated over and provided the kind of overcast that I’m normally looking for with long-exposure waterfall photos. Here’s a view (below) of Opal Creek taken from the footbridge that didn’t make the calendar:

The October image in the new calendar is from a roadside pullout that nobody seems to stop at, and yet it provides a very nice view of Mount Hood and the East Fork Hood River (below). This spot is on a rise along Highway 35, just south of the Highway Department maintenance yard.

If you stop here in mid-October, you’ll enjoy quite a show, with brilliant Cottonwood lighting up the valley floor in shades of bright yellow and gold and Oregon white oak in the foreground providing orange and red accents. And if you pick a clear day after the first snowfall, Mount Hood will light up the horizon with a bright new jacket of white.

How bright are the fall colors? Here’s the exact scene a few months earlier, for comparison:

Like the earlier scene near Bennett Pass, this viewpoint is gradually becoming obscured, too. You can see the difference in the two Ponderosa pines on the left side of the photo. The larger, more distant tree (at the edge of the photo) hasn’t changed as visibly, but the younger Ponderosa (second from left) is quickly blocking the view of the river.

For comparison, here’s a photo from 2008 showing just how much the younger pine has grown, along with the Oregon white oak in the right foreground:

In this case, however, the East Fork Hood River is on the side of tourists and photographers. The river is famously volatile, thanks to its glacial origins on Mount Hood, and periodically undercuts the steep banks here, taking whole trees in the process. This is a scene of almost constant change, and I won’t be surprised if the younger Ponderosa nearest the river eventually becomes driftwood on its way downriver!

The October image is also from the Hood River Valley, and also a roadside view. This well-known scene is located on Laurance Lake Drive, just off Clear Creek Road, near Parkdale. Thanks in no small part to Oregon’s statewide planning laws, this remains an operating farm more than a 170 years after the area was first cleared by white settlers.

The patch of Cottonwoods at the center of the field that provide the fall color show have been growing there for some time, too — or at least they are descendants from an earlier grove. This view (below) from the 1940s shows how the area appeared when most of the roads were still gravel and twenty years before the reservoir we know as Laurance Lake was even constructed. This image is from the Oregon State Archives, and staged for tourism ads, as you might guess!

Here’s a tip if you’re exploring the Hood River Valley in October and the Cottonwoods have turned. At about the same time the Western larch along the upper stretches of the East Fork and east slopes of Mount Hood area also turning to their fall shades of yellow and gold.

In fact, the November calendar photo was just a stop on the way for me as I headed up to the mountain to take in the Western larch colors. These photos feature the east side of Mount Hood and its many groves of Larch as viewed from the slopes of Lookout Mountain, and are among those that didn’t make the calendar this year.

For December, I chose another scene along the East Fork Hood River, albeit lesser known. This spot (below) is near the confluence of the East Fork with Polallie Creek, and was captured after a couple days of freezing fog in the upper Hood River Valley:

This is one of my favorite times to be in the forest, though it can be a bit treacherous! The unmatched scenery makes the slippery trip worth it, as the frosted forests combine with the fog to create a truly magical scene.

Here are a couple more images from that day in the freezing fog that didn’t make the calendar:

Since switching to Zazzle to produce the annual calendars, I’ve had a back page to work with, and I have used this space to feature a few wildflower photos from the past year (below).

Each wildflower image has a story behind it, and among the most memorable is the Buckwheat in the lower right corner. This little plant was growing at the summit of Lookout Mountain (below), in the Badger Creek Wilderness, east of Mount Hood.

Buckwheat is a tough, low-growing, drought tolerant wildflower that thrives in the rocky soils there, but what made the spot memorable were the thousands (millions?) of Ladybugs swarming on the summit that day. Entomologists tell us that several inspect species migrate to ridges and mountains from adjacent valleys to mate, keeping their gene pool stable and healthy in the process, but I’m thinking they might just enjoy the mountain views, too?

The Wild rose in the top row is also in foreground of this image of Crown Point and the Columbia River Gorge (below). I considered this image for the calendar, but skipped it until I can capture a more prolific flower display in the foreground… maybe next year!

Finally, the white Mockorange in the center of the bottom row was captured at this somewhat obscure spot along Butcher Knife Ridge (below), in the West Fork Hood Valley. This was another also-ran as a calendar image, but watch for some exciting news in a future blog story about this corner of Mount Hood country!

If you’d like a calendar, they’re easy to order online for $25 from Zazzle. Just follow this link:

2020 Mount Hood National Park Campaign Calendar

They’re beautifully printed by Zazzle, ship quickly and make nice gifts! And I’ll also be donating all proceeds to Trailkeepers of Oregon (TKO).

_______________________

If you’ve followed the WyEast blog for a while, you probably noticed that things look a bit different around here, as of this month. It’s true, a mere eleven years after I made this first post…

…I’ve changed the WordPress theme for the blog. But I do admit that I didn’t have much choice. My most recent posts were having serious formatting problems, as in my last post (below) where the column text and photos were out of alignment. Other less obvious problems were popping up when publishing new posts, making what for a very cumbersome process.

In digging through pages of tedious WordPress documentation to figure out what was up, I finally came across this unwelcome message:

What? My theme is retired? Since when..? And who says!

Ah, the pace of progress. So, recognizing that things would only get worse, I’ve spent the past couple weeks customizing a “modern” theme called “Hemingway” to retain as much of the look and readability of the blog as I can. I’ll probably need to continue tweaking the settings, so thanks in advance for your patience!

If you’re wondering about the new banner, the backstory is that I originally created banner below. However, it didn’t work well with the new theme, which resizes the banner for whatever device the user is viewing, and decapitated Mount Hood in the process! Aargh!

So, I opted to continue the “misty forest” look from the original banner, which was from a scene captured in 2008 near Horsetail Creek in the Gorge. The new banner draws from image captured of Horsetail Creek, Katanai Rock, located in Ainsworth State Park.

The original Katanai Rock image was taken several years ago, on a spring day as storm clouds were just clearing from the walls of the Gorge, creating a mystical scene that Tolkien might have dreamed up:

To create the banner, I converted the original image to sepia and did some toning to soften the shadows a bit:

[click here for the large view of Katanai Rock]

Look closely at the large view and there’s a wispy waterfall floating down the west side of Katanai Rock and lots of massive old trees wrapped in mist… it’s Rivendell!

Finally, the new banner incorporates just the top of Katanai Rock in a crop that allows it to adjust to anything from an iPhone to a 27″ monitor like the one I’m working on, right now:

So, that’s how the new look came about! And as with each of the previous 11 years on the blog, I’m looking forward to another year of articles. I’ve got lots of topics in the hopper, and hopefully some that you will enjoy and find worth reading.

Thank you for stopping by over the past year, and thank you for being a friend of Mount Hood and the Columbia River Gorge!

I’ll see you on the trail in 2020!

Tom Kloster • WyEast Blog