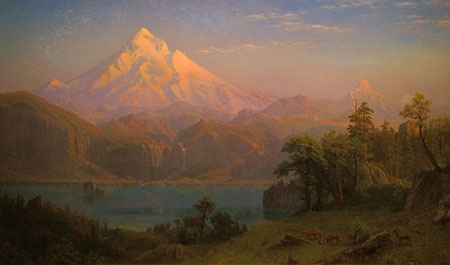

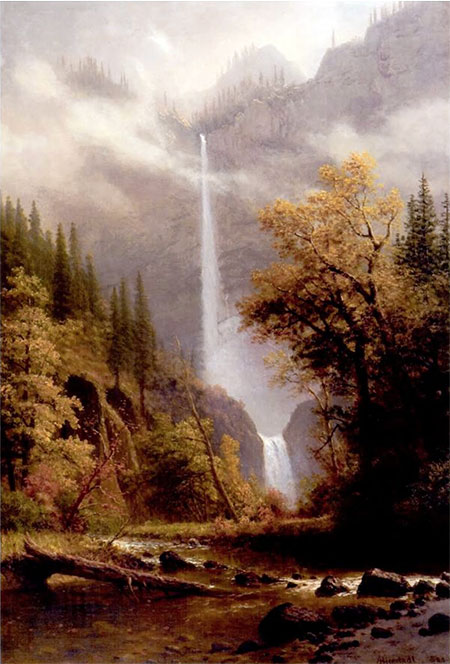

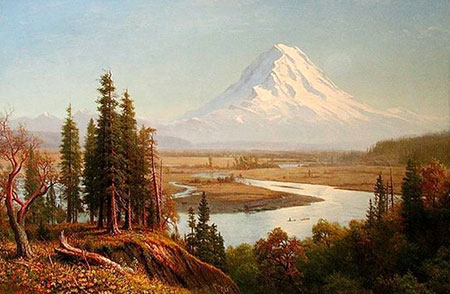

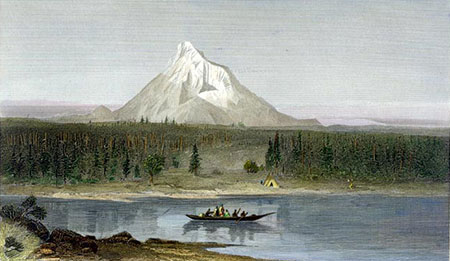

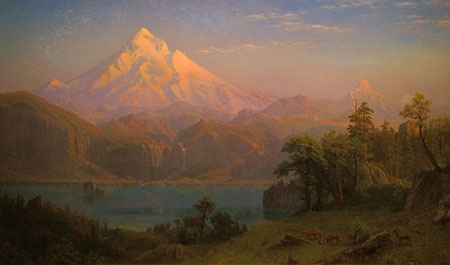

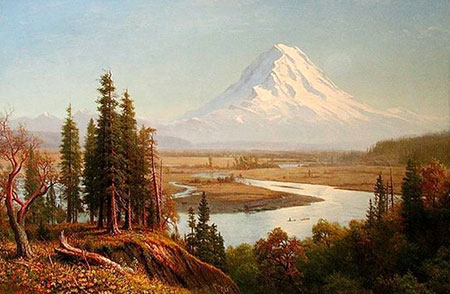

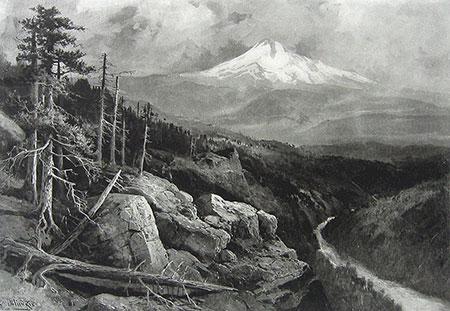

Albert Bierstadt’s magical 1869 vision of Mount Hood

Long before white settlement had reshaped the American West, artists were traveling with early explorers to capture scenes of the stunning landscape and native peoples. This was the first view most Easterners in our young country had of places like Yellowstone, the Grand Canyon and Yosemite — places that would eventually become the crown jewels of our national park system.

And just as Mount Hood and the Columbia River Gorge are still believed by many to be part of the national park system, the painters and photographers of the mid-1800s captured them in their untouched state along with the other great places in the West. This article tells the story of how Albert Bierstadt and other artists of the era came to Oregon to capture the beauty of our mountain and the Columbia River, how their art helped inspire the original national parks movement and how their work still resonates with us today.

Longing for Nature

In the mid-1800s, the Industrial Revolution was in full swing in the cities along America’s east coast, and the public was beginning suffer from its effects. In booming New York, massive tenements were constructed to house factory workers in apartments that were often without daylight and access to fresh air or plumbing.

Crowded life in New York’s tenements of the mid-1800s led to a public yearning for a greener world

Coal burning was creating stagnant clouds of pollution that coated our eastern cities in soot, and there was a growing yearning for the greener, simpler world of our agrarian past. The carnage of the America Civil War in the 1860s only compounded the nostalgia. Thus, the Romantic period of the 19th Century was a movement that responded to pressures of the Industrial Revolution, glorifying a past rooted in nature.

Simple access to light and fresh air was a luxury in New York’s mid-1800s tenements

The Romantic movement emphasized the sublimity and beauty of nature, and dominated American art during this period, especially the untamed American West that was glorified in monumental landscapes by artists of the Hudson River School.

Thomas Cole’s 1847 “Home in the Woods” envisioned an idyllic green world in stark contrast to life in the big cities of the Industrial Revolution

The Hudson River School was a mid-19th century American art movement embodied by a group of landscape painters whose aesthetic vision came to define romanticism in this country. The paintings for which the movement is named originally depicted the Hudson River Valley and its founding is generally credited to Thomas Cole, who painted until his early death in 1848.

The Second Wave

Cole was followed by a second wave of Hudson River artists who grew to become celebrities in their time, including Frederic Edwin Church, Albert Bierstadt, and later, Thomas Moran.

Bierstadt and Moran became best known for their epic paintings of the untamed American West in the last half of the 1800s. Their paintings were the popular equivalent of movie blockbusters today, with huge canvases dramatically unveiled in sensational public events.

Thomas Moran’s dramatic scene of a storm over the Grand Canyon still wows viewers today

While the Hudson River School artists often glorified nature, they also brought people into their scenes in an idealized way, as part of the epic landscape. Native Americans were portrayed as nobly beautiful in these romanticized landscapes, and conversely, Bierstadt also created similarly noble scenes of white settlers migrating west in his Oregon Trail paintings, on their way to claim lands belonging to Native Americans.

The two ideas are a strange contradiction, given the de facto genocide that was unfolding upon Native Americans in the West when Cole and Bierstadt were creating these masterpieces. But the Hudson River artists were glorifying nature (and American Indians) as a divine creation of their Christian God, and so it makes sense that their paintings also fit the “manifest destiny” justification for westward migration of white settlers, however contradictory.

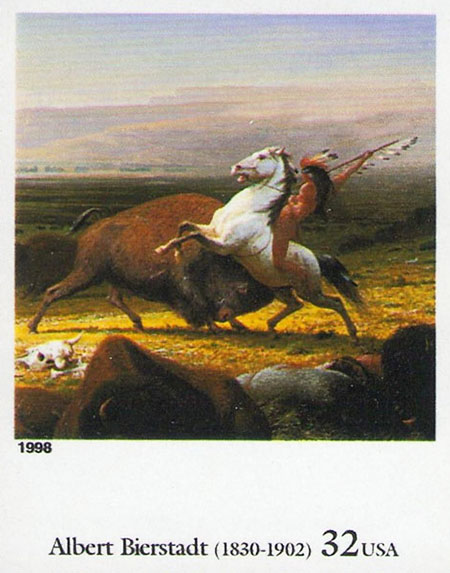

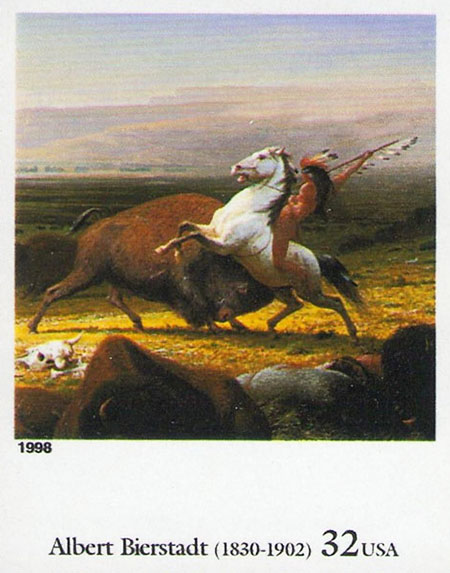

Just as Bierstadt’s “Last of the Buffalo” (1889) brought the reality of the slaughter of America’s bison herds to Easterners in the 1800s, it now provides a window into the past for new generations of Americans learning about the western migration. It was the last of his monumental paintings, and directly triggered the first bison census, leading to protections for the species.

While Hudson River artists worked in dramatic realism, their romanticized scenes were often an idealized hybrid of multiple locations captured by the artists in their field studies in the West. Both Cole and Bierstadt made regular trips to what were often very remote, rugged locations for their studies, then returned to their studios to create the massive masterpieces that evoked the overall sense of wonder they had experienced in the West.

Bierstadt’s “Oregon Trail” (1869) helped establish the enduring mythology of westward migration.

This is often a point of criticism for these painters, as the country was also experiencing the invention of photography, and realism in painting was increasingly being held up against tintype photos by early photographers to gauge their accuracy. Yet, just as photographers attempt to capture light and subject in a way that captures the drama and feeling of a place, Hudson River artists were similarly compiling scenes that captured their own memories and experiences in a West.

The author on a recent pilgrimage to view Bierstadt’s “Among the Sierra” (1868), on permanent display in the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

The Hudson River artists also influenced the creation of our first national parks, with masterpieces of Yellowstone and Yosemite that persuaded Congress to establish the very first protections for our most spectacular wild places. Albert Bierstadt painted many scenes in Yosemite over the years, along with many other wild places across the West that would ultimately be protected from exploitation.

Bierstadt in Oregon

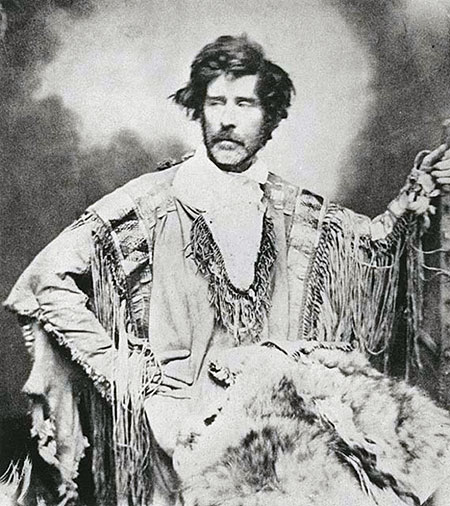

Albert Bierstadt was born in Solingen, Germany, in 1832, but soon immigrated with his parents to New Bedford, Massachusetts at the age of two. He began drawing as a child, and by his early twenties was painting with oils as part of the Hudson River School movement. He would paint over 500 paintings over the course of his remarkable life.

In 1859, he traveled west with a U.S. Government survey crew, sketching scenes that he would later turn into his epic masterpieces in his studios in New York and Rome. This was one of many trips west for Bierstadt over his long painting career. One of these paintings, “Landers Peak, Rocky Mountains”, sold for $25,000 after it was completed in 1863, an astronomical figure for that time (Bierstadt later purchased this painting from the buyer to give to his brother).

Albert Bierstadt “Landers Peak, Rocky Mountains” (1863)

[click here for a large view]

Bierstadt’s huge, panoramic paintings were an immediate sensation with the public, and he quickly became the preeminent painter of the American West during the mid-1800s.

Bierstadt first came to Oregon beginning in the early 1860s, and painted Mount Hood at least four times — the most of any Pacific Northwest scene. He made at least three extended trips to Oregon, twice in the 1860s and later in the 1890s, as his career was winding down.

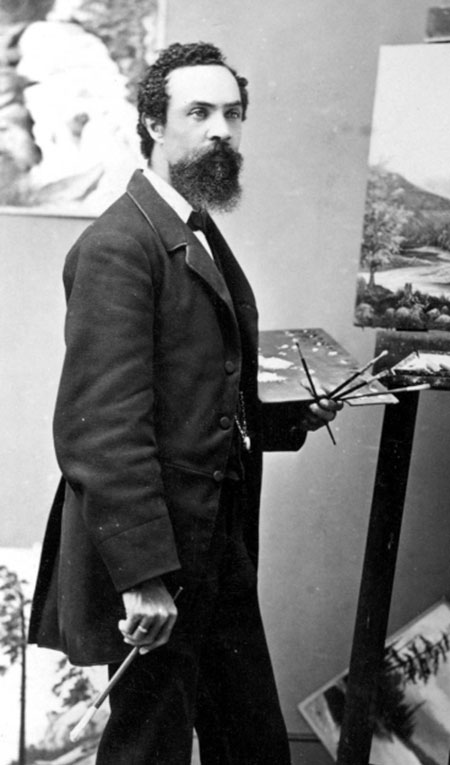

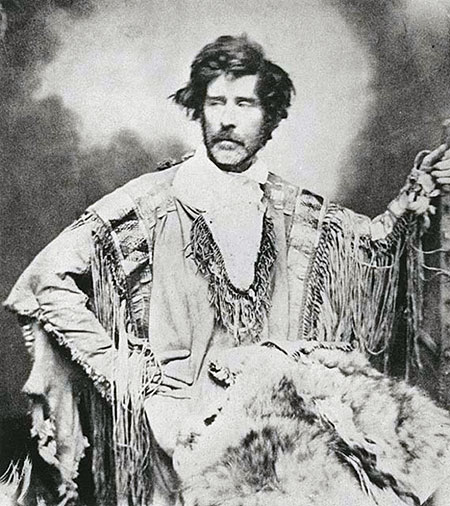

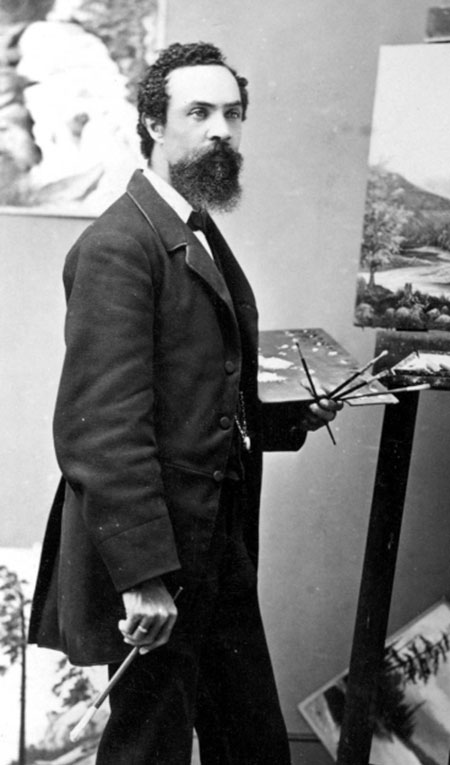

Albert Bierstadt in the mid-1800s

This undated, possibly earliest Bierstadt work shows a scene on the Columbia River, with trio of canoes and a towering version of Mount Hood, basking in alpenglow. At first, the peak looks more like Mount Rainier, but a closer look shows a reasonably accurate rendering of the Sandy Headwall and other west face features, albeit with a healthy dose of artistic license:

One of Albert Bierstadt early paintings of Mount Hood (date unknown)

Another early Bierstadt work from the same lower Columbia River perspective shows alpenglow lighting up the mist along the river and, notably, what appears to be Barrett Spur on the mountain’s north flank, makes this a somewhat more literal image:

Albert Bierstadt “Morning Thirst – Mount Hood” (date unknown)

In the fall of 1863, Bierstadt made his second trip west and painted a pastoral scene on the north side of the mountain, as viewed from the Hood River Valley. This spare, relatively small portrayal (just 20 inches wide) is much more literal, with many familiar north face features captured, along with Lookout Mountain, to the east. Bierstadt also used artistic license to include Mount Jefferson peeking over the west shoulder of Mount Hood:

Albert Bierstadt’s 1863 view of Mount Hood from the Hood River Valley

This painting is thought to have been in preparation for the much larger paintings of Mount Hood that would follow. His companion on the 1863 trip, Fritz Hugh Ludlow, recalled the visit in a published account that followed:

“After a night’s rest, Bierstadt spent nearly the entire morning making studies of Hood from an admirable post of observation at the top of one of the highest foothills — a point several miles southeast of town, which he reached under the guidance of an old Indian interpreter and trapper” (Atlantic Monthly. December 1864)

In 1865, Bierstadt completed a very large piece that pictures an idealized, but much more literal Mount Hood towering over the Columbia Gorge. Multnomah Falls and even Larch Mountain are included in the artist’s blend of iconic features. Mount Jefferson and the Three Sisters float on the distant horizon:

Albert Bierstadt’s massive 1865 painting of Mount Hood created a public sensation

[click here for a large version]

This massive painting measures ten feet wide by six feet tall, and created a sensation with the American public when it was unveiled. In 1876, it was one of six monumental paintings selected by Bierstadt for display at the Paris World’s Fair, bringing Mount Hood to international fame.

The painting was one of many portraits of Mount Hood that become part of the public’s imagination of the West, finally putting a face on the towering icon that settler accounts had described at the end of the Oregon Trail. Today, this painting can be viewed at Gerald Peters Gallery in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

This stunning work shows the mountain and Gorge in much more detail than his earlier studies. Mount Hood’s most familiar features — Barrett Spur, Yocum Ridge and Illumination Rock — are detailed, along with Multnomah Falls, Latourell Falls, Phoca Rock and Sherrard Point atop Larch Mountain.

Detail from Bierstadt’s “Mount Hood” (1865)

The Gorge peaks are oddly deforested in this view. While logging in the Gorge cleared most of the slopes around Larch Mountain by the end of the 1800s, the forests probably would have been much more intact in 1865, when access to the Gorge was still extremely limited, so the barren slopes are more likely artistic license. Yet, Bierstadt did include trees in the foreground that are true to the Gorge, with rugged conifers typical of ancient Douglas fir that have survived the extreme Gorge elements, twisted white oaks and a billowy group of bigleaf maple in the right foreground.

In 1869, Bierstadt completed what to many is his ultimate masterpiece of Mount Hood: a smaller (five feet wide by just over four feet tall), more refined version of his 1865 work that brings all of the elements of the earlier painting with much more dramatic, evening light.

Albert Bierstadt 1869 refinement of his more famous 1865 Mount Hood portrait

[click here for a large version]

This final piece is housed right here our very own Portland Art Museum, and worth the price of admission, alone. Bierstadt’s final take on our mountain remains the most glorious of the Romantic period paintings of Mount Hood.

While it’s easy to critique Bierstadt’s creative rearranging of geography, it’s also understandable: visitors today still seek that “perfect spot” where all of the pieces of the tableau that make up the Gorge and Mount Hood experience.

The view from Sherrard Point on Larch Mountain comes close, for example, with its 360-degree view encompassing the Gorge, Columbia Delta, Mount Hood, the string of big Cascade volcanoes in the distance and the craggy top of Larch Mountain and its magnificent stand of Noble fir filling the foreground. A mind’s eye recollection of the view of being there brings all of these pieces together as part of the memory, just as Bierstadt combined elements in his paintings that were about the experience of being there, not simply documentation of the elements.

A closer look at Bierstadt’s 1869 masterpiece shows Multnomah Falls (left), Latourell Falls (center), Larch Mountain and Sherrard Point (center right) and Mount Jefferson in the distance

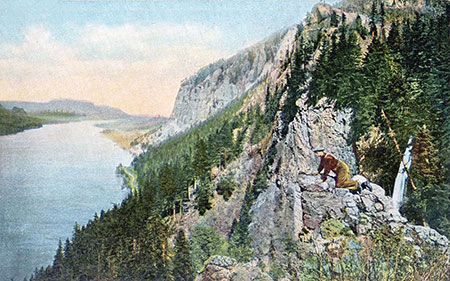

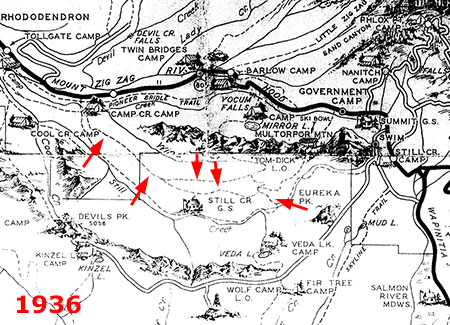

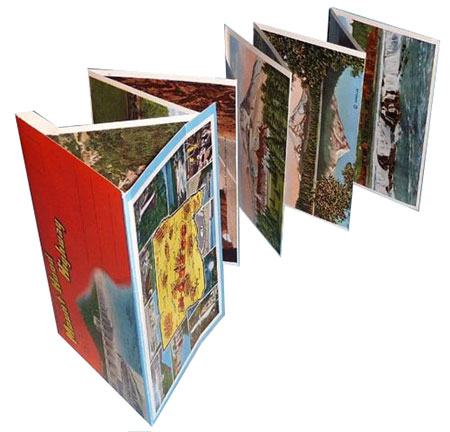

Mid-1900s Mount Hood Loop Highway visitors picked up postcard folios at souvenir stands and roadhouses along the loop looking to capture their memory in a similar way. These little booklets contained a series of cards showing off the most iconic spots in the Gorge and on the mountain that a visitor might have seen in a day spent driving the loop, but just as Bierstadt rearranged scenic elements, the folio covers of these postcard collections often blended the images to create a mosaic that pulled all of the pieces together.

1940s Loop Highway Postcard Folio

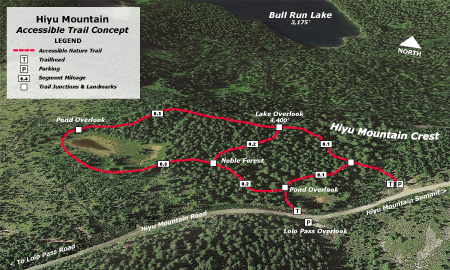

More recently, cartographic artist Jim Niehues created a magnificent, modern-day mental map of the area with just enough cartographic license to capture the feeling of being there, while still preserving the basic geography of the Gorge and mountain.

Like Bierstadt before him, Jim Niehues brought a mind’s eye view of Mount Hood and the Gorge together in this stunning piece of cartographic art

Bierstadt visited the region long before the south side of Mount Hood had become the focus of tourism in the 1920s, with the arrival of the loop highway. Instead, his visits took him to the north side of the mountain to points along the Columbia River and in the Hood River Valley that were accessible by rail.

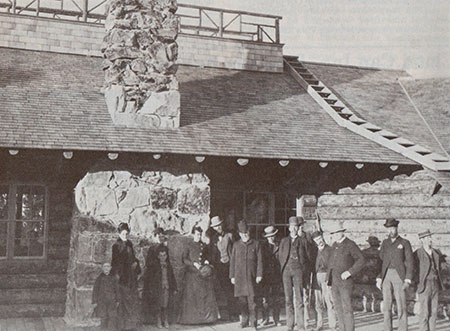

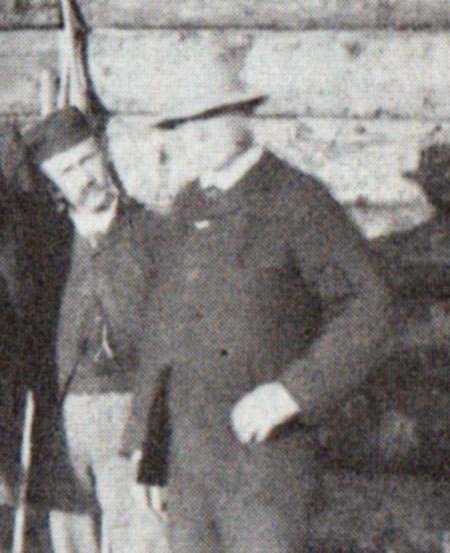

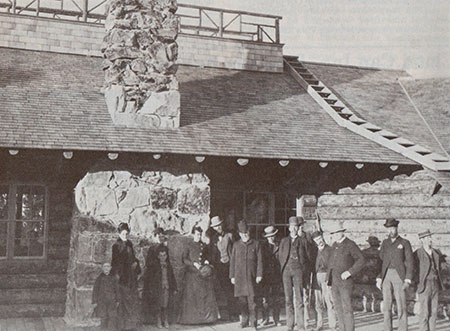

It’s unknown if he actually visited the slopes of the mountain on his visits in the 1860s and 70s, when his famous works of Mount Hood were created, but Jack Grauer’s “A Complete History of Mount Hood” shows Bierstadt visiting Cloud Cap Inn in 1890. According to Grauer, Bierstadt is third from the right in this rare photo, wearing a light hat:

Closer views suggest and older and grayer Bierstadt:

Albert Bierstadt would have been 60 years old at the time of this visit. Clearly, this trip shows that he remained an intrepid explorer in his later years. The trip to Cloud Cap Inn, which had opened just one year prior, entailed a train ride from Portland to Hood River, where the horse-drawn Cloud Cap Stage was waiting to take visitors on a rugged, five-hour ride up the mountain to the lodge that was not for the faint-of-heart.

Albert Bierstadt stood here!

Today, you can still see the ruts of the original stage road that led to the inn at grades in excess of 20 percent. Since the 1940s, a new road has criss-crossed the original stage route in a graded series of switchbacks, allowing modern-day visitors to marvel at the ordeal that earlier visitors like Bierstadt endured on the way to Cloud Cap!

Bierstadt’s Other Works in the Region

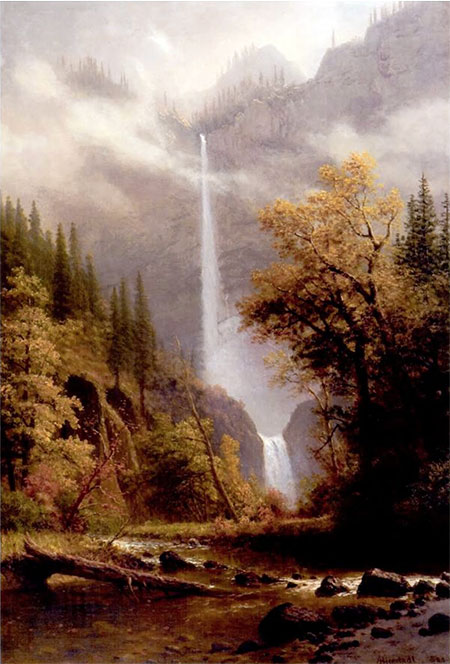

While Bierstadt’s epic paintings of Mount Hood were widely known and celebrated, his rendering of Multnomah Falls is less known, possibly because it came later in his career, and at just 3 by 5 feet, was relative “small” compared to his huge panoramic scenes. Bierstadt captures Multnomah Falls with much literal accuracy on a typically misty autumn day:

Bierstadt’s “Multnomah Falls” (late 1800s)

[Click here for a large version]

Today, Bigleaf maples still frame the falls in gold in autumn, but Bierstadt did add a rocky bluff beyond the falls to add depth to the painting:

Though this painting is undated, Bierstadt likely created it before a log bridge spanning the lower falls was built in the early 1880s:

The stream detail in the foreground gives a sense of what it must have been like to approach our tallest waterfall in its truly wild state, before today’s developed paths and viewpoints were built:

Bierstadt painted the Columbia River as a foreground for most of his Mount Hood scenes, but surprisingly, a view down the Columbia Gorge from near Crown Point was not one of his subjects. This undated Bierstadt painting of the Columbia captures a scene that may be on the east side of the Cascades in desert country, perhaps in the vicinity of today’s Horsethief Butte State Park, looking west:

Albert Bierstadt’s Columbia River scene

If Bierstadt did make it to the mid-Columbia region, it’s unclear whether he visited Celilo Falls. It surely would have provided all of the elements for one of his panoramic paintings, complete with a Native American villages and fisherman working the salmon runs, yet there are no paintings of Celilo among his works.

Instead, we can only wonder what his take might have been, perhaps alogn the lines of Thomas Moran’s stunning portrayal of “Shoshone Falls” (1900) on the Snake River:

Thomas Moran’s “Shoshone Falls” (1900)

Bierstadt painted several of the big Cascade Mountain volcanoes, including this view of Mount Adams, perhaps inspired by alpine meadows above Takhlakh Lake the mountain’s west side:

Albert Bierstadt’s “Mount Adams” (1875)

He made a few paintings of Mount St. Helens, all from the shore of the lower Columbia River. This scene shows Mount Adams (or possibly Mount Rainier) peeking over the shoulder of St. Helens:

Albert Bierstadt’s “Mount St. Helens” (date unknown)

Bierstadt painted mighty Mount Rainer from the tidal flats of Puget Sound, near Tacoma, in a scene that includes our native Madrona trees (on the left), a nice touch of literal accuracy:

Albert Bierstadt’s “Mount Rainier” (date unknown)

Finally, for avid hikers this small, untitled Bierstadt piece sure looks like Mount Jefferson as viewed from northwest of Jefferson Park, above the Whitewater trail:

Untitled Bierstadt piece — is this Mount Jefferson?

At the time Bierstadt was in Oregon, this would have been a remarkably rugged, remote area for anyone reach, so it’s probably more likely coincidence that this so closely resembles Jefferson, but who knows? Maybe we will discover another undocumented chapter in his travels in the future.

The Other Painters

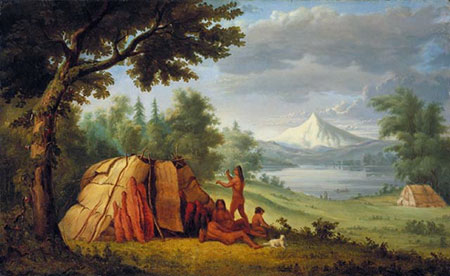

There were many fine paintings of Mount Hood made by other artists during the 1800s, when Bierstadt was visiting the region. Explorer and self-taught artist Paul Kane is best known for his early portraits of native people in the West. Kane was among the earliest to arrive in Mount Hood country and paint the mountain while spending the winter of 1846 at Fort Vancouver.

Paul Kane in the 1840s

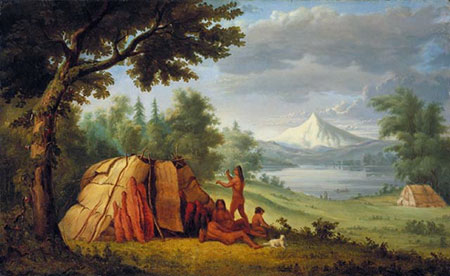

Among Kane’s best known work is a scene depicting Chinook people living along the lower Columbia River in the early 1850s, with Mount Hood as the backdrop:

Paul Kane’s “Chinook Indians in front of Mount Hood” (1850s)

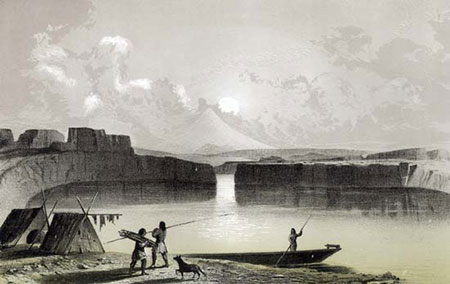

John Mix Stanley was another prominent explorer and self-taught painter who visited the region. Stanley first came west in 1842, and was known for his portraits of Native American life captured during the first half of the 1800s.

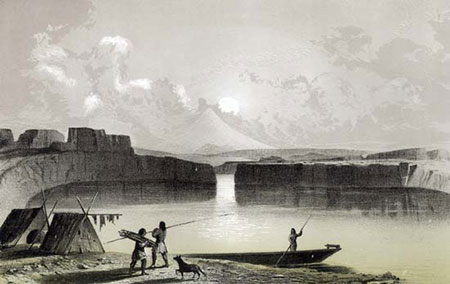

John Mix Stanley

His 1855 lithograph of Mount Hood shows tribal life along the Columbia, as viewed from near The Dalles:

In 1865, a fire at the Smithsonian destroyed much of his work, and Stanley set about recreating some of the most memorable scenes from his travels in the West from sketches and memory.

His trip through the Columbia Gorge by boat in 1853 apparently made a special impact on Stanley, and his 1870 “Mountain Landscape with Indians”, captured these memories in composite. This painting was also likely inspired by the success of Bierstadt’s panoramic 1865 view of Mount Hood, as well:

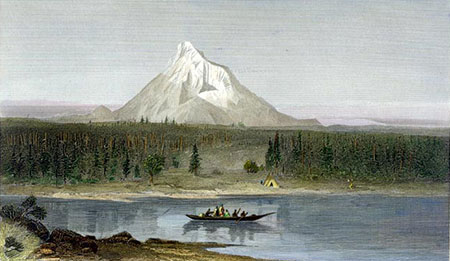

Stanley’s first rendition of Mount Hood from the Columbia River (1870)

In 1871, Stanley created a much larger (five by eight feet!) version of the same scene with a more stylized Mount Hood. This masterpiece blends the west face of Mount Hood, familiar as the view on Portland’s skyline, and elements from throughout the Gorge, including a Native American village:

Stanley’s panoramic 1871 masterpiece of Mount Hood and the Columbia River

[click here for a large version]

Boston artist Robert Swain Gifford created a somewhat bizarre version of Mount Hood in 1874 that continues to circulate widely today as a collectable print:

R.S. Gifford’s stylized 1874 take on Mount Hood

This exaggerated view attempts to capture the mountain from the north side, in the vicinity of Hood River, but is oddly cartoonish in comparison to other, more realistic works that were being created at that time.

In the 1880s, Gifford created this much more accurate etching of Mount Hood from the Columbia River narrows at The Dalles:

R.S. Gifford’s 1880s engraving of Mount Hood from The Dalles

Though he was not known for his western art, Gifford’s 1880s rendering of Mount Hood has been widely published and remains popular with print collectors today.

Another painter by the name of Gifford (though unrelated) was Sanford Robinson Gifford, another Hudson River School artist. Sanford Gifford created this dreamlike view of Mount Hood and the Columbia River in 1875:

Sanford Robinson Gifford’s “Mount Hood” (1875)

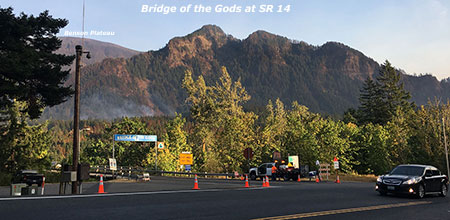

Sanford Gifford’s scene is not too far from reality, with elements that nearly exist in reality as viewed from the north side of the river near today’s Washougal.

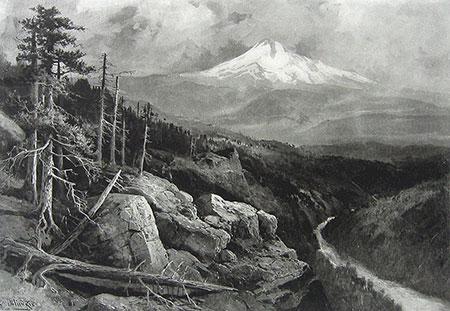

Artist Frederick Ferdinand Schafer was a German immigrant with a studio in San Francisco. He painted scenes from throughout the West, including this view of Mount Hood described as being from The Dalles:

Ferdinand Schafer’s “Mount Hood” (date unknown)

Schafer worked from field notes and sketches, which might explain why this scene “from The Dalles” looks nothing like the area. Instead, this perspective of the mountain could be from the upper Hood River Valley, possibly merging the canyon of the East Fork Hood River with the mountain as it appears from the valley. The trees on the right look a lot like mountain hemlock, though they might be inspired by Ponderosa pine that are found through the east Gorge.

Connecticut painter Gilbert Munger was another student of the Hudson River School, and a friend of John Mix Stanley. Munger served as an engineer in the Civil War, and traveled west after the war as part of an emerging movement of more literal, grounded landscape painting that adhered to geographic accuracy.

Gilbert Munger in the 1870s

Munger painted at least two versions of Mount Hood in the 1870s that show his characteristic attention to accuracy, both from the Hood River area:

Both of Munger’s pieces faithfully show the iconic, open foothills that define the east Gorge today from Hood River eastward. His paintings have enough detail to show the Eliot Glacier on Mount Hood’s northeast slope with surprising accuracy for the time.

San Francisco artist Julian Walbridge Rix created one of my favorite early paintings of Mount Hood, an 1888 scene from the Hood River area that faithfully captures both the geography of the mountain and the local geology and ecology of the east side forests:

“Mount Hood” (1888) by Julian Rix

Rix was a member of San Francisco’s Bohemian Club and may have been encouraged by Albert Bierstadt as he began his landscape painting career in the 1870s.

A truly pioneering painter who should be more celebrated here in Mount Hood country is Grafton Tyler Brown. He painted in the late 1800s, and was notable as the first African American painter to work in the Pacific Northwest and California. Brown was born in Philadelphia, where his father was a freeman and abolitionist.

Grafton Tyler Brown in his studio

Brown moved to San Francisco while in his twenties and working as a lithographer. He later lived in Portland and Victoria, British Columbia during his painting career. Brown painted at least two surviving paintings depicting Mount Hood. The first was completed in 1884 and shows a bright scene along the Hood River, near the town of Hood River:

Brown’s “Mount Hood” (1884)

The detail on this piece looks almost like it was painted with modern acrylics.

A later piece completed by Brown in 1889 shows a classic Columbia River scene near The Dalles with Mount Hood reflecting in the river:

John Englehart arrived later on the scene, painting western landscapes in the 1890s and early 1900s. In 1902, Englehart moved his studio from San Francisco to Portland, where he exhibited in the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition in 1905.

Englehart’s Mount Hood paintings follow the Hudson River School style, but the art world had moved on to European impressionism by the time he was creating these scenes, and he never attained the acclaim of earlier Hudson River artists.

This Englehart scene shows Barrett Spur on the left, suggesting a view from the west or northwest, perhaps along the Sandy River:

Mount Hood scene by John Englehart

This Englehart painting is a different take on the mountain, with a river scene that seems too small to be the Columbia River, though there’s no reason to assume that the artist didn’t simply stylize that detail for the purpose of his composition:

Englehart’s vision of Mount Hood… and the Columbia River?

These Englehart pieces appear to be from the 1890s.

Eliza Barchus was another pioneering artist based in Portland who made her name at the 1905 Lewis & Clark Exposition, where she won a gold medal for her landscapes. Barchus was widowed at the age of 35, and her artwork became the sole source of income for her family at a time when very few women were working artists. She ran a downtown studio in Portland and later expanded her business to include construction and homebuilding.

Eliza Barchus in the 1890s

Eliza Barchus in her Portland studio in the early 1900s

Barchus painted romantic scenes of Mount Hood, the Columbia Gorge, Multnomah Falls and many other familiar scenes here in Mount Hood country during her long life (she lived to be 102 years old).

“Mount Hood” (early 1900s) by Eliza Barchus

William Samuel Parrott also had a studio in downtown Portland in the late 1800s, and specialized in Pacific Northwest landscapes. Like Munger, his paintings were geographically accurate, yet also captured the romantic sensibility of the Hudson River School. This Mount Hood scene by Parrott is in the Portland Art Museum collection, though not currently on public display:

William Parrott’s rendering of Mount Hood (late 1800s)

There were other landscape artists working the Pacific Northwest during the late 1800s, but the public was moving on toward new trends in art. The popularity of the Hudson River style had faded from public favor by the turn of the 20th Century, replaced by interest in impressionism and other more modern artistic movements.

It’s not coincidental that the romantic landscape era of painting faded with end of the Western frontier, as the two were intertwined in the American imagination. But art from the era still offers a lasting sense of this remarkable period in our history in way that early photography or writing from the period don’t fully capture. Thanks to the vision and audacity of artists like Bierstadt, we can still experience what it felt like to live in that time of wonder and exploration.

Bierstadt is still inspiring our imagination…

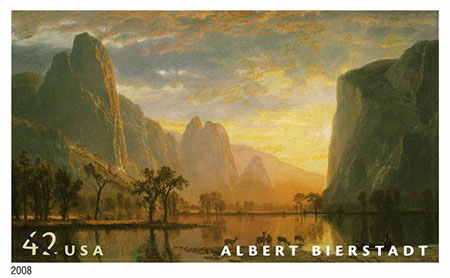

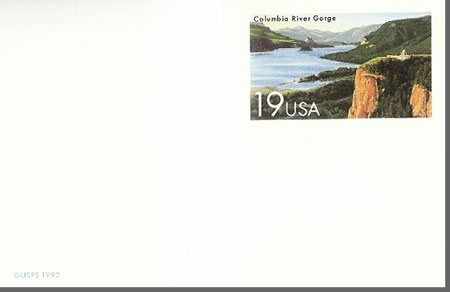

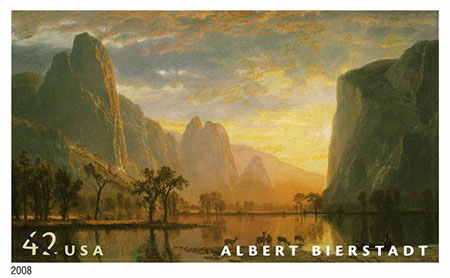

Bierstadt died in 1902, twelve years after his last visit to Mount Hood. For many decades during the era of modern art, his work was dismissed and ignored as out of fashion, but he was rediscovered in the 1970s. His legacy has since been celebrated in popular art, including a couple of U.S. postage stamps in recent years.

Bierstadt’s “Last of the Buffalo” celebrated by the U.S. Postal Service in 1998

Why the resurgence in interest? While Bierstadt’s work in the 1800s served to capture the pristine spectacle of the American West, today it serves as a reminder of what once what, and what might be — what should be — as we move into an new era of restoration in our country’s evolution.

There’s an ironic tragedy in the fact that Bierstadt’s career centered on celebrating the wild, unspoiled beauty of the west, yet culminated with “The Last of the Buffalo” a stark warning of what we had already lost — and what he had witnessed in the half-century he spent documenting the American West. We’ll never know if Bierstadt had misgivings about the effect his paintings had in spurring western migration, but he was clearly aware of the effects that white settlement of the West had wrought.

One of Bierstadt’s many stunning takes on Yosemite appeared on this stamp in 2008

It’s also no accident that I’ve used Bierstadt’s Mount Hood masterpiece as the backdrop for the Mount Hood National Park Campaign website. In this magical piece, Bierstadt brought together the essential elements of what makes the Mount Hood area so unique, and so worthy of Park Service protection as a national shrine.

It’s true, much restoration is needed and a completely different management mindset is in order to bring Mount Hood and the Gorge back to their former ecological state. But Bierstadt’s dreamlike portrayal provides the perfect inspiration to aim for that lofty vision, and break away from our current, unsustainable path of incremental over-development and exploitation.

Postscript

A disclaimer from the author upon posting this article: while I’m an avid fan of the Hudson River School artists who traveled to the American West in the 1800s, I’m certainly no scholar on the subject! I welcome any corrections or additions that more knowledgeable readers might provide.

The author on a recent visit to see the great western landscape paintings at the Smithsonian American Art Museum

This article has been in the works for about five years, as I’ve not only had to learn the subject matter, but was also surprised to discover that the life of Albert Bierstadt is poorly covered by historians. This may be due to his art falling out of favor by the time of his death in 1902, but hopefully the future will bring a more thorough look at this remarkable American.

Bierstadt’s “Mount Hood” (1869) is on permanent display at the Portland Art Museum (courtesy Portland Art Museum)

In the meantime, make your own pilgrimage to the Portland Art Museum to see our very own Bierstadt Mount Hood masterpiece in person. You will surely be inspired by his timeless vision of our mountain!