High on Mount Hood’s broad east face is the Newton Clark Glacier, third largest of the twelve named glaciers on the mountain. Many assume a hyphen must be missing in what appears to be two surnames, especially since the two major glacial outflows from this glacier are separately known as Newton Creek and Clark Creek. Who is this Newton character… and what about Clark?

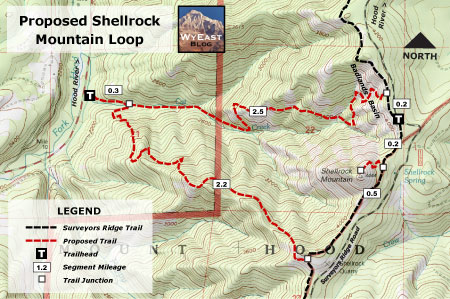

Instead, it turns out that Newton Clark was just one man who made his place in local history as one of the early surveyors mapping the Mount Hood area. And in a rarity among place names in Oregon, his full name made it to our maps, where our modern naming rules limit honorary place names to surnames. It also turns out that nearby Surveyor’s Ridge, with its popular mountain biking trail, is also named for Newton Clark, albeit anonymously.

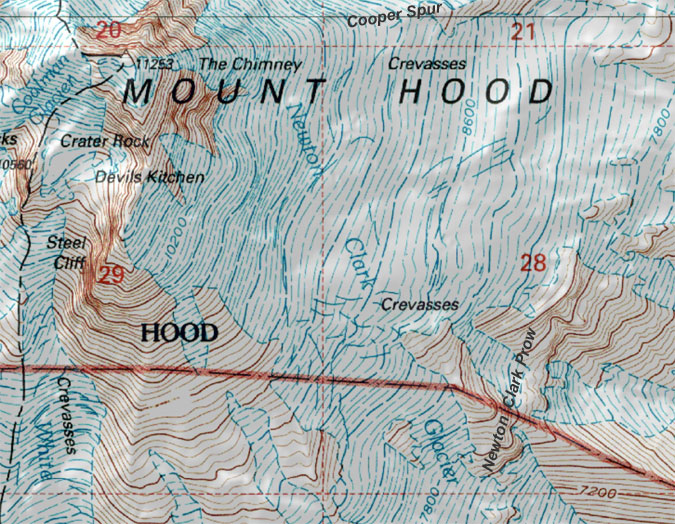

The sprawling glacier named for Newton Clark is unique among Mount Hood’s glaciers: it’s wider than it is long! While glaciers like the Eliot, White, Coe and Reid flow down the mountain in rivers of ice, the Newton Clark Glacier is draped like a big ice blanket on the east face of the mountain high atop a steep bench formed by the Newton Clark Prow, a massive lava outcrop that prevents the glacier from flowing any further down the mountain.

The Newton Clark Prow splits the glacier into its twin canyons, Clark Canyon to the south and Newton Canyon on the north. At nearly 8,000 feet in elevation, this jagged rock outcrop once divided a much larger ice age glacier into two rivers of ice that left today’s massive Newton Clark Moraine behind, a medial moraine that once had rivers of ice as high as the moraine flowing on both sides (you can read more on that topic in this blog article). Today, the Newton Clark Prow forms the rugged head of Newton Canyon, with summer meltwater from the glacier tumbling over its cliffs in dozens of waterfalls.

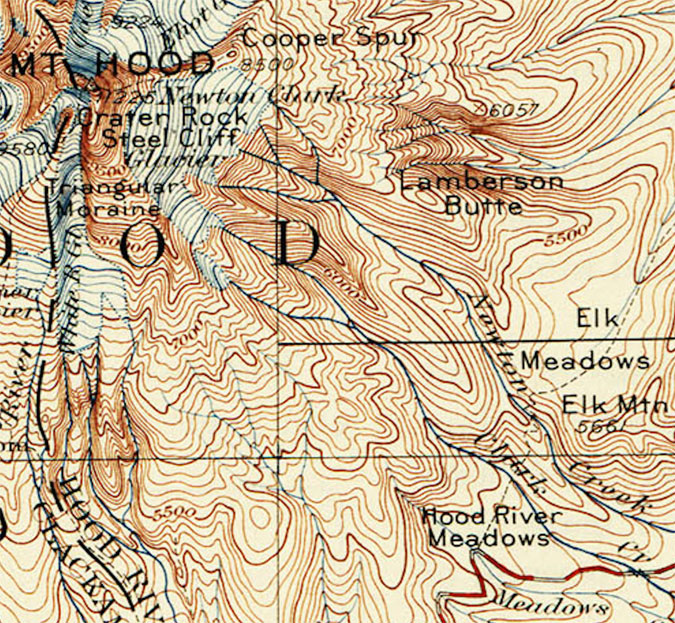

The broad Newton Clark Glacier is bordered on the north by Cooper Spur, a long, gentle ridge that extends from Cloud Cap to the summit of Mount Hood. At 8,514 feet, the summit of Cooper Spur is among the highest points in Oregon that can be reached by trail, and one of the more popular hikes on the mountain. The view from the top of Cooper Spur provides a close-up look the rugged, crevassed surface of the Newton Clark Glacier.

From below, the Newton Clark Glacier actually looks stranded (below), sitting unusually high on the mountain, with its crevasse fields spreading out in multiple directions as the glacier sprawls above the cliffs of the Newton Clark Prow.

Downstream, the Newton and Clark canyons eventually merge at the southern foot of the Newton Clark Moraine, where the flat, mile-wide floor of the East Fork Hood River valley begins. Here, the arms of the ice age ancestor of the Newton Clark Glacier continued for miles down the mountain toward Hood River, creating the broad, U-shaped valley we travel today on the OR 35 portion of the Mount Hood Loop Highway.

Surprisingly, the two glacial outflows don’t merge on the valley floor. Instead, they each flow into the East Fork Hood River separately, about a mile apart. Both Newton and Clark creeks are notoriously volatile glacial streams, each changing course on the floor of the East Fork valley during recurring flood events.

Of the two outflows, Newton Creek is the largest and most volatile stream, repeatedly sending massive debris flows down the East Fork Hood River valley over the years and washing out OR 35 in the process (more on that later). Clark Creek is less violent, but still a powerful glacial stream that challenges Timberline Trail hikers attempting to ford it during the summer glacial melt.

Now that we’ve met the Newton Clark Glacier and its sibling streams, what about the man behind the name?

Who was Newton Clark?

Newton Clark was born in Illinois in 1838 and soon moved as a child with his family to Wisconsin as pioneer settlers. Clark spent his youth there, becoming an exceptional student and later studying surveying at the Point Bluff Institute.

In October 1860, Newton Clark married Scottish immigrant Mary A. Hill, and the two resided in North Freedom, Wisconsin. Just one year later, in September 1861, 23-year old Newton enlisted in the 14th Volunteer Infantry, Company K Wisconsin volunteers of the Union Army. His company served in 14 battles under General Ulysses. S. Grant in Civil War battles across the south.

Like so many in their Civil War generation, young Newton and Mary’s married life was put on hold during his four years of service. Mary remained in Wisconsin with their young daughter during Newton’s infantry service, undoubtedly anxious for her young husband’s return from our nation’s deadliest war.

When he left for battle, Newton said “If I never come back remember that you have our little Minnie to live for, work for her and she will be a comfort to you.” Newton later returned from battle, but their little Minnie died during his time away at war.

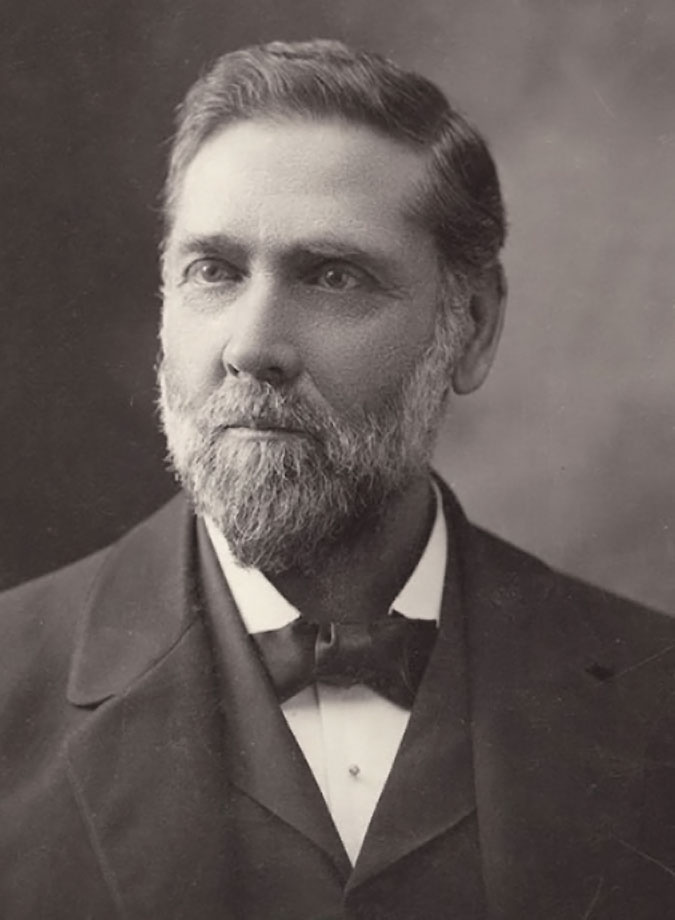

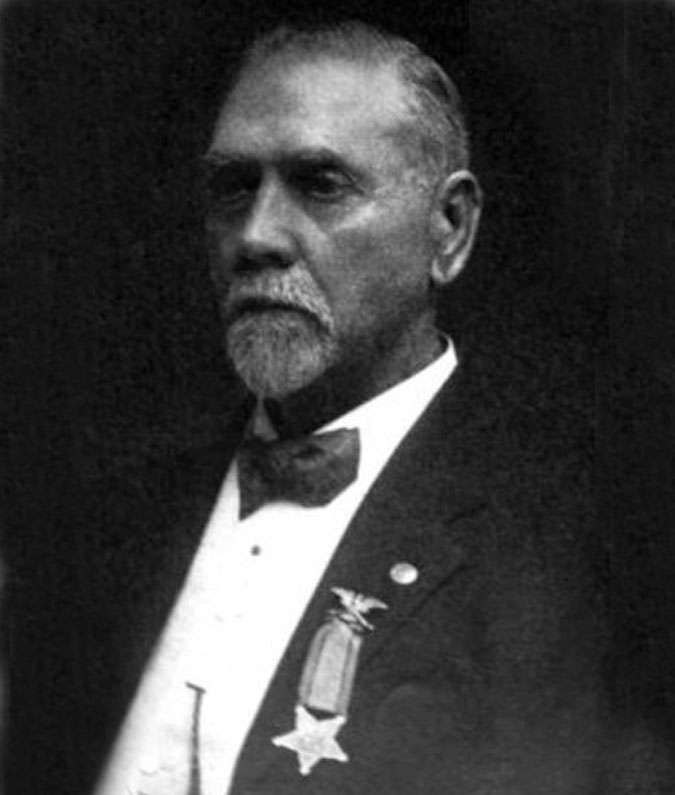

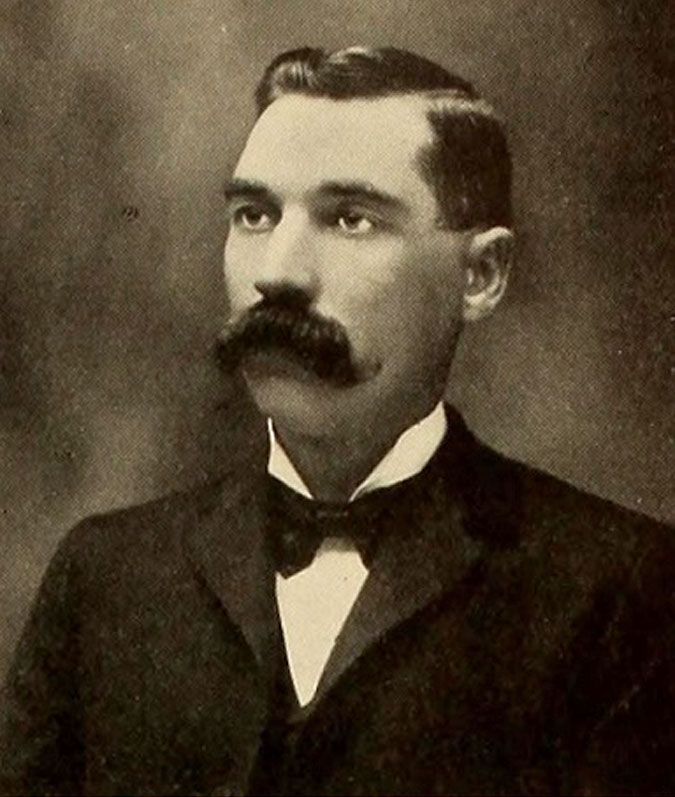

Newton Clark served as Quartermaster during his Civil War enlistment, and he furnished the flag that was raised above the Vicksburg, Mississippi courthouse when the war was ended on May 9, 1865. After the war, Newton was an active veteran with the Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.) fraternal organization. The above portrait above was taken late in is life, and proudly shows his G.A.R. insignia.

The G.A.R. was much more than what we think of with today’s fraternal organizations. Following the Civil War, the G.A.R. emerged as among the first and largest advocacy group on the nation’s political scene, dedicated to both political causes and the benevolent interests of their veteran members.

The G.A.R. was an important arm of the Republican Party (at the time, the progressive party in American politics), and in this capacity the organization was deeply involved in the reconstruction that followed the war. Among their efforts, the G.A.R. actively promoted voting rights for black Civil War veterans. They also became a racially integrated organization at a time when the emerging Jim Crow era was about to stall civil rights in this country with another century of racial segregation and persecution of black Americans. At its political peak in the late 1800s, the G.A.R. had nearly half a million members.

The G.A.R. also focused on advancing Republican candidates to public office and promoted patriotism and veteran’s rights across the country. This included providing pensions for veterans, creating hundreds of war memorials so that the Civil War might never be forgotten and establishment of Memorial Day as a national holiday, a legacy many of us celebrate without knowing of its origins.

In his later years, Newton Clark served as an officer in the Ancient Order of United Workmen (A.O.U.W.) for decades, a fraternal benefit society formed to provide mutual social and financial support for its membership after the Civil War. By the late 1800s, it was the largest fraternal organization in the country, and one that Newton continued to serve until his death.

Newton and Mary’s Life in the West

Soon after Newton’s return from his service in the Civil War, he and Mary moved west to the new Dakota Territory that had been created in 1861, just as the Civil War erupted. There, the Clarks farmed as pioneers in what is now the state of South Dakota.

The old Dakota Territory was massive, encompassing today’s North and South Dakota, most of Montana and the north half of Wyoming until statehood came to Wyoming and the Dakotas in 1888-89, long after the Clarks had moved again, this time to Oregon.

During their time in the Dakota Territory, Newton and Mary continued to have children, in the wake of losing their baby daughter Minnie, eventually adding two daughters and a son to their young family. The Clarks built the first frame house in Minnehaha County, where they farmed on a homestead located two miles from today’s town of Sioux Falls. Newton also worked as a surveyor of public lands for eight years, where he laid out the sections and townships in much of the Dakota Territory.

Newton Clark entered politics while in the Dakota Territory, too. He served as school superintendent, and was chairman of the board of county commissioners in Minnehaha county for several years before serving as a state legislator in the Dakota Territorial Legislator in the early 1870s. Newton Clark’s public service in the Dakota Territory put his name on the map of today’s South Dakota, with Clark County and the county seat of Clark, South Dakota named for him.

The grasshopper plagues that swept the high plains in mid-1870s eventually drove Clark from the Dakota Territory, and he continued his family’s migration west to Oregon in 1877. That year, he left Mary behind to care for the children in the Dakota Territory while he joined up his parents, Thomas and Delilah Clark, who had been living in Colorado.

Together, Newton and his parents traveled three months overland in the summer of 1877, arriving in the Hood River area on September 1. Mary Clark and their three children, William, Jeanette and Grace, eventually joined Newton and his parents in 1878, settling into their new home in Oregon.

Newton later said “I tried farming on my homestead in Dakota, but after two years of successful crops of grasshoppers, I became a disgusted with that form of agriculture and struck for Oregon, driving a team overland.”

Newton and Mary Clark arrived in Oregon with almost no money to their name, and set about creating a new life in Hood River. They were among the first pioneers to settle there, and Newton initially found work cutting cordwood and splitting shingles for other valley settlers. By 1878, he was able to purchase 160 acres on the west side of the Hood River Valley, where they built their family home. Newton’s parents built their home on an adjoining parcel.

Newton Clark said later of their new home “We found the Hood River Valley as nature had designed it and habited by a handful of the pioneers… the salubrity of the climate, its freedom from storms of wind and lightning of summer and its frigid blizzards of winter as compared with the Dakotas, all delighted us.”

Newton soon began taking contracts with the federal government to survey public lands in the rugged western and southern parts of Hood River County, establishing the section lines in the Upper Hood River Valley and surrounding mountain country that are still the basis of our maps today. Most of these areas would become part of today’s Mount Hood National Forest. Loggers in the early 1900s were still reporting survey marks on trees left by Newton Clark’s crews more than 30 years later.

Like today’s immigrants to Oregon, Newton Clark was drawn to explore the unmatched scenery that we sometimes take for granted. He was among the first to summit Mount Hood and he was also a member of the first party of white men to set eyes on iconic Lost Lake.

Surveying and exploring in Mount Hood country the 1880s was difficult and dangerous. Trips into the mountains took days, with Clark’s crews carrying heavy supplies on their backs and packhorses. There were few trails, so much of the travel was cross-country, through dense, virgin forests.

Like other pioneer explorers of Mount Hood, Clark eventually had a feature on the mountain named for him. For unknown reasons, his full name was used in naming the Newton Clark Glacier. Perhaps this was to prevent confusion with the many features in the West named for William Clark, of the Lewis and Clark Expedition? It remains among the few places in Oregon to feature the full name of its namesake.

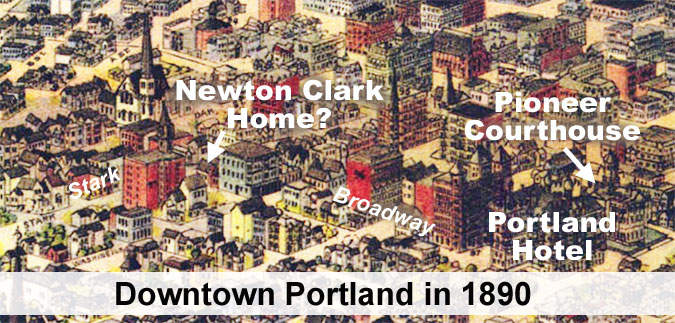

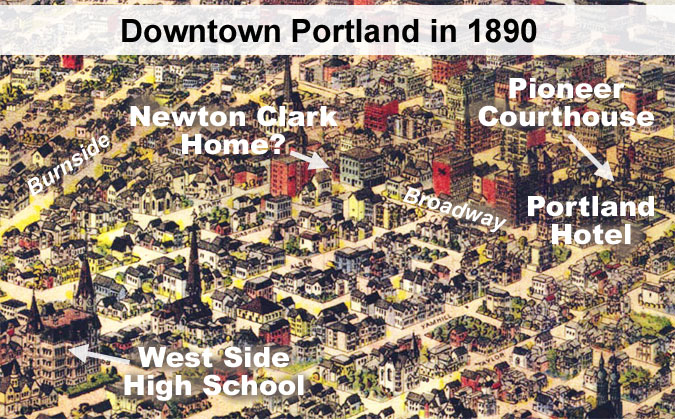

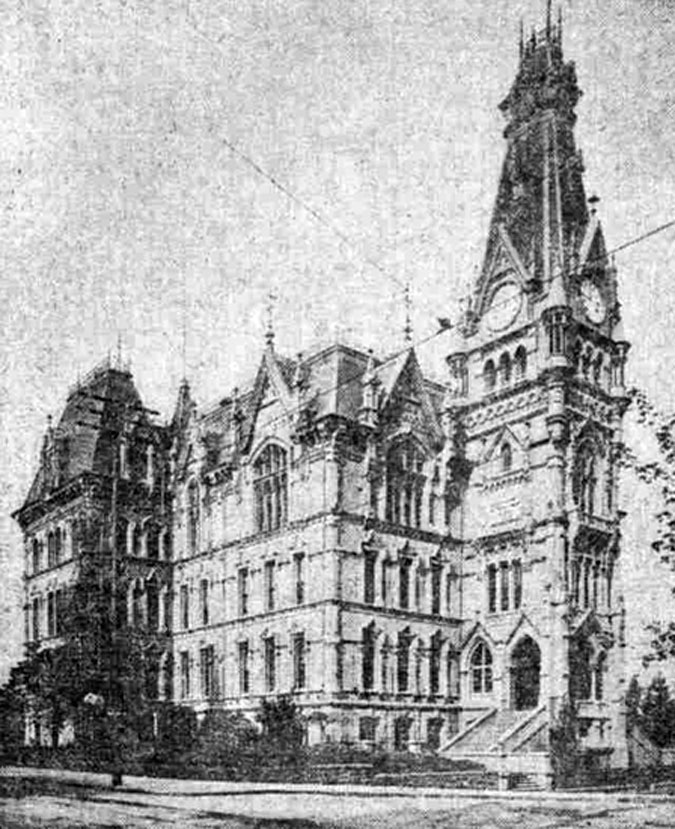

The Clarks left Hood River in 1888 when Newton was elected Grand Recorder of the A.O.U.W., his beloved fraternal older, though he retained some of his property in the Hood River Valley until his death. He served in this capacity with the A.O.U.W. for the next 20 years, with the family living in downtown Portland in a house at “400 Broadway”. Under Portland’s historic address system, this would have been at the corner of Broadway and Stark, where the Hotel Lucia now stands today — in theory, as least.

This illustrated map from 1890 shows a home located at the southeast corner of Broadway and Start, a few blocks from the once iconic Portland Hotel that stood where today’s Pioneer Courthouse Square is located.

While the 1890 map seems to provide a plausible case for where the Clarks lived in Portland, the fact that today’s historic Hotel Lucia (once called the Imperial) was built in 1909 at this corner clouds that history. The Clarks moved back to Hood River that year, which might make a plausible case for a new hotel going up where home had been, but newspaper accounts show them living at the same home in Portland a few years later, with their daughter. So, more research is needed to know just where the Clarks lived in Portland.

The family returned to Hood River in 1909 when Newton retired from his A.O.U.W. office and built a new home on a hill above town that became their retirement residence.

During these later years in Hood River, the Clarks spent summers at a cabin Newton built at Lake Lyttle on the Oregon Coast, in today’s town of Rockaway Beach. Unlike today’s travelers, they didn’t follow roads to Rockaway Beach. Instead, they took the new Oregon Pacific Railway that had recently opened a route through the Coast Range from Hillsboro to Tillamook.

It’s unknown if Newton’s parents joined him when the Clarks moved to Portland in 1888, but his father died in 1892 and historic accounts show his mother living with the Clark family in Portland when she died in 1905, at the age of 98. So, one possibility would be that Delilah Clark joined her son’s family when Thomas Clark passed away in 1892, though there are no history accounts to confirm this.

What is clear is that Newton was close enough to his parents to bring them west to Hood River with his family in 1877, and later, to bring his elderly mother into his home in Portland. Somewhere out there, a portrait of the extended Clark family exists, and I’m hopeful a reader of this article might be able to help with that.

Newton Clark’s Family

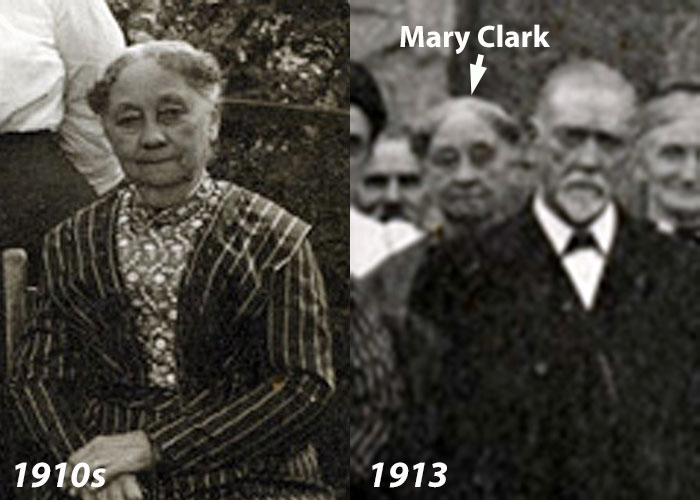

True to the era, less is known about Newton Clark’s wife, Mary, beyond her husband’s description of their life together. She was a native of Edinburgh, Scotland, and according to the historical accounts available, she shared Newton’s passion and determination in their adventurous life as pioneers.

Two of Newton and Mary’s children died while the parents were still living, baby Minnie in the early 1860s, while Newton was serving in the Civil War and later, their adult daughter Grace (Clark) Dwinell, in 1910.

Grace finished school in Portland after the family had relocated there in 1888, and became a West Side (now Lincoln) High School graduate. What history is recorded about Grace describes her as outgoing and with a beautiful singing voice that she would often entertain with at family gatherings.

Grace Clark met young Frank Dwinnell while on a trip to visit family in Wisconsin, and he followed her back to Portland, where the two married. They moved back to Wisconsin for a time and started a family, but sometime in the late 1890s, Grace contracted tuberculosis — then called “consumption” and the leading cause of death at the turn of the century.

At the time, Grace attributed her illness to the harsh climate in Wisconsin, and the family relocated back to Oregon. After initially recovering from the disease, her tuberculosis eventually returned and Grace died in 1910 at the age of 37. Her funeral was held at Newton and Mary’s new home overlooking Hood River. Frank Dwinnell later moved back to Wisconsin with their young son and daughter to be near his family.

Two of Newton and Mary Clark’s children survived them, including their son William Lewis Clark and daughter Jeanette (Clark) Brazelton. Jeanette’s life is the least documented of the three Clark children who survived childhood, except that she became Mrs. W.B. Brazelton and appeared to living with her parents in their Portland home at the time of their deaths in 1918. I was unable to discover more about her life or even where she was buried for this article, so hopefully a reader will have more of Jeanette’s history to share.

William Lewis Clark followed his father’s footsteps and became a prominent civil engineer in Oregon. William was eleven when the family moved west to Oregon, and after finishing school in Hood River, he worked on his father’s survey crews. At age 19, William went to work for the Northern Pacific Railroad and later the Southern Pacific, overseeing various construction projects across the West.

William married Mary Ann Mabee in 1880 (later records show her as Estella Mabee), and the two would later have a son in 1899, Newton Mabee Clark, who would become a third-generation engineer in the Clark Family. Newton Mabee Clark attended Stanford University, graduating in 1916. He was enlisted in Stanford’s elite Student Army Training Corps, a unit of the U.S. Marines, and served in World War I. Newton M. Clark died in Seattle in 1975 and had no children.

In 1900, the year after his only son was born, William Lewis Clark left the railroads and became the City of Portland’s district engineer for next seven years. William returned with his family to Hood River in 1907, shortly before his parents made their own return to Hood River from Portland.

For the next ten years he worked in the flour and grain business for C.H Stranahan in Hood River before returning to public service in 1917 for the Oregon Highway Department, at a time when the Historic Columbia River Highway construction was in full swing.

William finished his career with the City of Hood River, serving as city engineer from 1922 to (apparently) his death in April 1930, at the age of 62. Mary Ann (also listed as Estella) Clark moved to Seattle sometime after William’s death, apparently to be near their own son. She died in 1950 at the age of 75.

Back to Portland to serve his beloved A.O.U.W

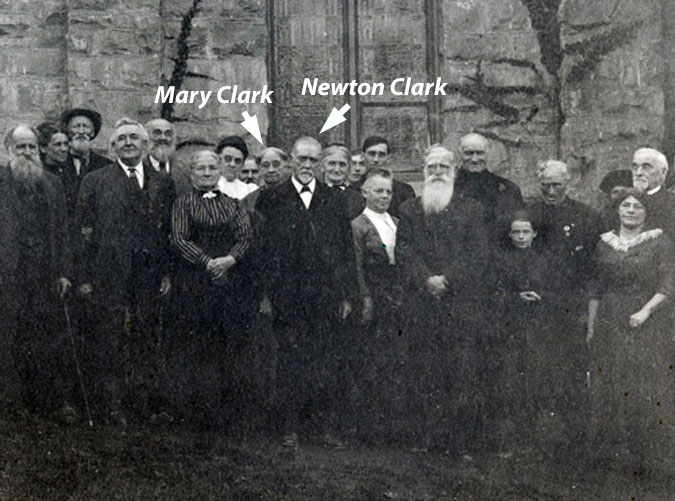

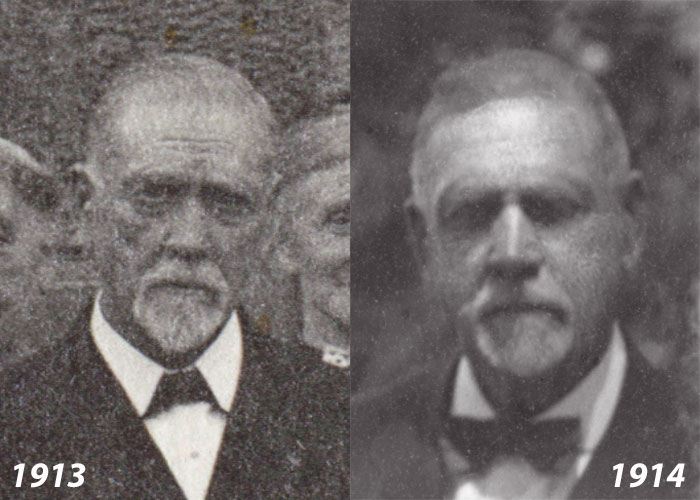

Historical accounts show that Newton and Mary had moved back to Portland in about 1914. He had been called back from retirement to once again serve Grand Recorder of his beloved A.O.U.W. in the wake of so many members of the organization being called to serve active duty in World War I. If this timeline is correct, the Clarks spent just five years in Hood River after their 1909 return, and the photos in this article of the Clarks taking part in community life in Hood River marked their final days living there.

Newton and Mary Clark both died in 1918, and remarkably, both were exactly 80 years and 24 days old at the time of their deaths. Newton died on June 21 of that year at his daughter Jeanette Brazelton’s home in Portland, which seems to be the home where Newton and Mary lived in during their previous 20 years in Portland. Despite a global influenza pandemic that year, Newton died of a “paralytic stroke”, according to historical new accounts.

Newton’s death was widely covered by newspapers in Portland and Hood River, and his funeral at Riverside Congregational Church in Hood River drew a large turnout from the community, including many of the surviving pioneers who had known the Clarks since the mid-1800s. However, Mary Clark was in failing health when her husband died, and she was unable to travel to Hood River to attend his service.

The Hood River Glacier published this tribute to Newton:

________________

Newton Clark

“A soldier, and a fighting one, for four years of his early manhood, and then a frontiersman, he experienced life as men of the following generations could not. It was a privilege to hear him recount tales of the days of the past. As everlasting as the hills and mountain crags he loved were the principles and rugged honesty of Newton Clark. He was loyal to the things he believed in and fought untiringly for their accomplishment.

“But few men knew that Mr. Clark had passed the age of 80 years. He walked with erectness and his step was firm. News of his death brought a shock of grief to all here last Friday. His comrades, men who knew him best, and loved him, and the families of pioneers, heard the sad news with pains of deepest regrets.

“Another of our pioneers has gone on the long trail, and we will miss him.”

The Hood River Glacier, June 27, 1918

________________

After the shock of Newton’s death, Mary seemed to be recovering and traveled to Hood River with Jeanette to visit their old home, returning in “better health and good spirits” according to news accounts. But on the morning of July 20, Jeanette found that her mother had died in the night at her home in Portland, just a month after Newton has passed away.

This tribute was published in the Hood River Glacier as the community mourned the loss of two of its most prominent pioneers:

________________

Newton and Mary Clark

“Married at North Freedom, Wisconsin on October 17, 1860, Mr. and Mrs. Newton Clark, of this city, have trodden the pathway of life’s long journey together longer than the most couples of Oregon. Yet few men or women who have not yet reached the three-score-and-ten mark are more active or vigorous than this sturdy couple, a typical product of the frontier and pioneer life.

“With all faculties alert and hale and hearty both are enjoying their old age. Both are possessed of an optimism and enthusiasm that youth might envy.”

The Hood River Glacier, April 6, 1916

________________

Though Newton and Mary Clark spent most of their years in Oregon living in Portland, their hearts were clearly in Hood River, where they had first carved out a life as Oregon pioneers. Not only did they choose to retire to Hood River (however briefly before Newton was called back to service), they also chose to be buried there, just a few steps from where they had buried their daughter Grace eight years before, and where their son William would be buried just twelve years after they died.

As I researched this article, I grew increasingly dumfounded that Newton Clark isn’t more celebrated in our local history. True, he does have a spectacular glacier named for him, which sure beats a street or local park, but his commitment to service puts him in rare company among the early pioneers in Oregon. Fortunately, his contemporaries recognized this and there are excellent historical accounts of his life, if only we take the time to discover them.

For the direct quotes from Newton Clark used in this article, I turned to a front-page interview and profile published on April 6, 1916 by the Hood River Glacier, just two years before his death. I’ve created a PDF of the entire article that [link=]you can read here.[/link]

For additional history, I turned to other news accounts from the era, as well as an excellent oral history largely written by Newton Clark, himself, in the History of Early Pioneer Families of Hood River, Oregon, compiled in 1913 by Mrs. D.M. Coon. Had these two efforts to record his life in his own words not been made, much of Newton Clark’s extraordinary contribution to our history would have ben lost to time.

And now, some unfinished business…

A Modest Proposal…

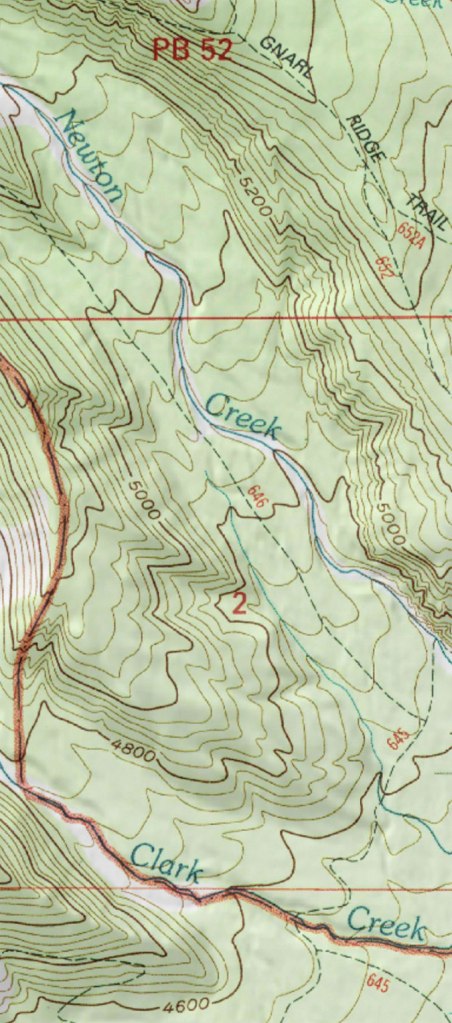

Call it a burr under my saddle, but when I learned decades ago that Newton Clark was one man, not a hyphenation, it bothered me that the two outflow streams were each given one half of his name. It struck me as a combination of historical ignorance and a degree of disrespect behind that decision, wherever it came from. So, where did it come from?

My guess is that these were lighthearted names attached by an early forest ranger, long ago, when most of the features in our national forests were casually named with little thought that these names would stick for centuries to come. Perhaps even Barney Cooper, the first district ranger for the Hood River area, named these streams in the early 1900s? And if Barney came up with the names, then surely he knew Newton Clark personally? After all, Hood River was a very small community in those early days. Perhaps it was Newton Clark, himself, who came up with these names while out on a survey?

History doesn’t provide an answer, but a look at some of the earliest topographic maps (below) confirms that both Newton and Clark creeks were named by the 1920s, when the Mount Hood Loop Highway had been completed and visitors began pouring into the area.

Whatever the reason behind the names for this pair of streams, the fact is that place names are one of the best and most durable ways to preserve our history for future generations. That’s why the confusion these names might cause remains a problem, at least in my mind.

Thus, I have a modest proposal, and it’s quite simple: add one word to the name of each stream and you not only solve the potential confusion, you also give Mary Clark her due. After all, would Newton have managed his remarkable life without a remarkable partner like Mary? Of course not.

Therefore:

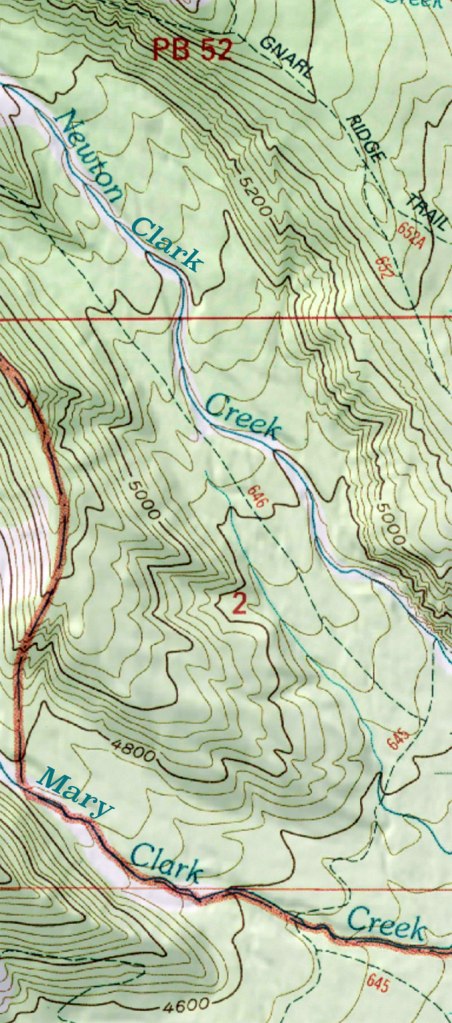

• Newton Creek should become Newton Clark Creek

• Clark Creek should become Mary Clark Creek

See how easy that is? And there’s some logic behind it, too, since Newton Creek carries the majority of the outflow from the Newton Clark Glacier.

Here’s how this would look on the topographic maps — easy fix!

Of course, when it comes to geographic names, nothing is easy! The Oregon Geographic Names Board (OGBN) is a volunteer panel administered by the Oregon Historical Society that serves as the overseer of geographic names in our state. New names or changes to existing names must be approved by this panel, and among their various criteria are support for public agencies (in this case the Forest Service) and the following:

“If the proposed name commemorates an individual, the person must be deceased for at least five years; a person’s surname is preferred; and the person must have some historic connection or have made a significant contribution to the local area.”

The Clarks have certainly passed the 5-year requirement, 102 years after their deaths. The second part of this requirement could be more of a challenge, but the fact that the Newton Clark Glacier already contains the full name of a historic figure would be my argument for making another exception, here. The last part is easy, as the contribution the Clarks made to the area is undeniable and well documented. Most importantly, the proposed change would also clear up potential confusion, something the OGBN also factors into their decisions.

So, I’ve added this to my list of OGBN proposals that I’ll someday submit when I have a moment, and when I do, I will reach out to the Hood River History Museum and U.S. Forest Service for their endorsements of the proposal, as well.

Exploring Newton Clark Country

Now that we’ve met Newton Clark and his family, the following is a short tour of the places named for him in Mount Hood country.

For Portlanders, the Newton Clark Glacier is on the dark side of the moon — it’s on the east face of the mountain, hidden from view from the rainy, evening side of the Cascade Range. But from the morning side of the mountain it’s prominent, and dominates the east face of Mount Hood.

Most who see the Newton Clark Glacier up-close view it from the crest of popular Cooper Spur, from nearby Elk Meadows or from Lookout Mountain, due east by five miles, across the East Fork valley. But some of the best views are from Gnarl Ridge, on the Timberline Trail. Here, the impressive scale of the Newton Creek canyon and the full width of the glacier are in full view. In summer, a series of tall waterfalls cascade from the glacier over the Newton Clark Prow and into Newton Canyon.

True to its name, Gnarl Ridge is home to hundreds of ancient, gnarled Whitebark pine that have survived the harsh conditions here for centuries. There’s no easy way to Gnarl Ridge. Both approaches, either from Cloud Cap or Hood River Meadows, involve a lot of climbing, though the scenery is some of the finest in Oregon. One advantage of the Cloud Cap approach is that no glacial stream crossings are required. However, several permanent, and potentially treacherous snowfields must be crossed on this highest section of the Timberline Trail.

The trail to Elk Meadows is among the most popular on the mountain, and deservedly so, and it provides a photogenic view of Mount Hood’s east face. This is a good family hike for a summer day, but it does require crossing Newton Creek without the aid of a footbridge — which can be an exciting experience. By mid-summer, Timberline Trail hikers have usually stitched together a seasonal crossing with available logs and stones, but expect wet feet when the water is high!

For a more remote experience, following the Newton Creek Trail to either Newton Creek or Clark Creek (or both) has dramatic views and a lot of rugged mountain terrain to explore. The route to the Newton Clark Trail crosses Clark Creek on a log bridge that has somehow survived this rowdy stream, then turns north and travels along Newton Creek before making a gradual climb along the northeast shoulder of the Newton Clark Moraine.

At the junction of the Newton Creek Trail with the Timberline Trail you can go right for a visit to Newton Creek or left to head over to Clark Creek. Or both, which is how I enjoy doing this hike.

Where Newton Creek canyon is vast and awesome, Clark Creek canyon has a few surprises, including lovely, verdant Heather Canyon, a side canyon with a string of splashing waterfalls.

The Clark Canyon headwall is also unique. The receding Newton Clark Glacier has left a wide, scoured rock amphitheater behind that has dozens of tiny streams running across its face in summer. To skiers, this is known as the “Super Bowl”, and it’s impressive to see close-up.

Downstream from the bowl, Clark Creek drops over a major waterfall (visible from the Timberline Trail) before reaching the debris-covered floor of the valley. This is where the Timberline Trail crosses Clark Creek, so if you like to avoid glacial stream crossings, it’s a nice turnaround spot for lunch. But if you don’t mind the crossing, a pretty waterfall on Heather Creek lies just a quarter mile beyond the Clark Creek crossing and makes for an especially lovely stop.

Heading the other direction on the Timberline Trail from the Newton Creek Trail junction quickly takes you to Newton Creek, proper. In most years, an impromptu rope helps hikers navigate a washed-out bank as you approach the chaotic canyon floor, and this is a preview of what can be one of the more difficult glacial crossings on the Timberline Trail.

Like Clark Creek, you can skip the crossing this glacial stream and simply enjoy a lunch atop one of the many table-sized boulders that fill Newton Canyon, with a fine view of the mountain. The Newton Clark Glacier is more prominent here, and the steep cliffs of Gnarl Ridge and Lamberson Spur rise along the far canyon wall.

Newton and Clark creeks are both thick with glacial till in summer, and don’t make good water sources, but Heather Creek runs clear and there’s a tiny creek flowing into Newton Canyon where the Timberline Trail approaches the canyon floor that provides both drinking water and a couple of shady campsites.

Exploring Surveyors Ridge

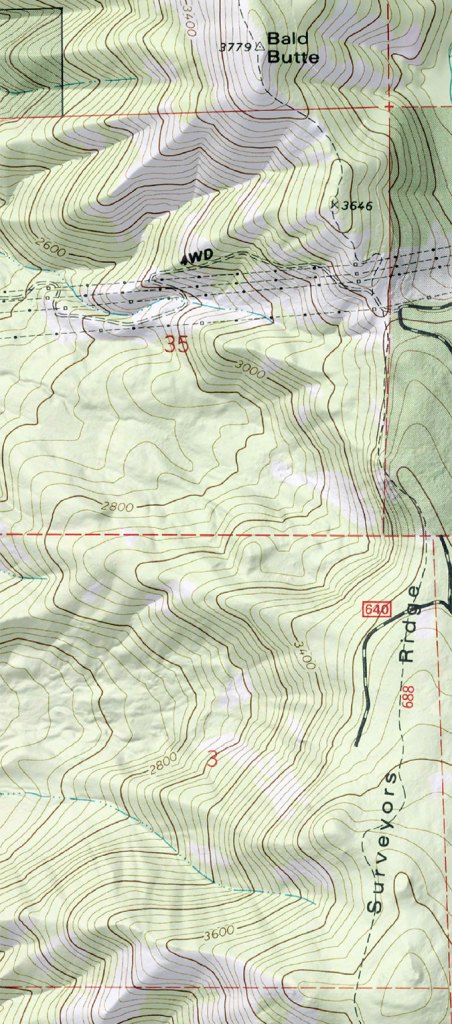

Though an anonymous tribute, Surveyors Ridge is also named for Newton Clark, and it’s well worth exploring. If you’re a mountain biker, I need say no more. You’ve been there and taken in the sweeping vistas!

But if you’re a hiker, I recommend making a trip to Bald Butte, which forms the northern end of Surveyor’s Ridge. It’s known to a few as “the other Dog Mountain” for its beautiful yellow balsamroot and blue lupine meadows in May and early June each year that echo the much more popular counterpart in the Gorge. Plus, the view of Mount Hood and the upper Hood River Valley from Bald Butte are stunning.

There are a couple of ways to get to Bald Butte. If you’re up for a stiff climb, you can take the Oak Ridge Trail (the trailhead is just south of the Hood River Ranger Station, off OR 35). This steep but scenic trail switchbacks up an open slope of Oregon white oak and spring wildflowers before entering forest and joining the Surveyors Ridge Trail. Turn left and hike a couple more miles and you’re on top of Bald Butte.

If you don’t mind driving a bit and are looking for a shorter climb, you can also take Pinemont Drive from where it intersects OR 35 (at the obvious crest between the middle and upper Hood River valleys) and follow this road for several miles to the east shoulder of Bald Butte. Watch for a gravel spur road on the right, shortly after you pass under a swath of transmission towers, and follow the spur to a trailhead under the powerlines.

The view from the trailhead is spectacular enough, but following the trail from here (which is really the old, primitive lookout road) to the summit of Bald Butte is even more sublime, passing several wildflower meadows that bloom in May and early June.

When you make the final ascent of Bald Butte, it’s hard to ignore the impact that off-road vehicles are having on the butte. Hopefully, the Forest Service decision to close most areas in the forest to these destructive vehicles will eventually be enforced. In the meantime, there’s a bit more on the subject in this earlier blog article on the fate of Bald Butte.

For a completely different slice of the Surveyor’s Ridge Trail, you can simply ramble the section north of Shellrock Mountain, where there are several big views of the mountain, plus a look into the weird terrain of Badlands Basin, where an ancient layer of volcanic ash and debris that has been carved into fantastic shapes. You can hike to this area from the Gibson Prairie Horse Camp.

The trail spur is located across the road, and if you turn left on the Surveyors Ridge Trail you’ll be heading toward views of Shellrock Mountain and Badlands Basin. Several handy boulders in the steep meadow pictured above make for a good destination for this short, easy hike. Turn right on Surveyors Ridge Trail, and you can take a shorter hike to Rimrock, where the views are somewhat overgrown, but still nice.

The 2006 Floods

Visiting the twin canyons of the Newton Clark Glacier is a great way to appreciate the raw power of the floods it has generated over the years. While Clark Creek can certainly hold its own, Newton Creek is the most fearsome stream on Mount Hood’s east side. Views along the lower section of the Newton Creek Trail (below) tell the story, with truck-sized boulders and stacks of 80-foot logs tossed about in a quarter-mile wide flood channel.

Much of the more recent devastation you see here occurred in the fall of 2006, when heavy rains fell on a blanket of early snow, and combined to send a wall of rock and mud down the canyon.

The debris flow roared down to Highway 35, blocking culverts, covering the road with boulders and washing out large sections of road bed. A similar event was occurring on the White River at the same time, temporarily cutting off access to the Mount Hood Meadows resort from both east and west. As sudden and violent as this event seemed, in reality it was part of an ongoing erosional process as old as the mountain, itself.

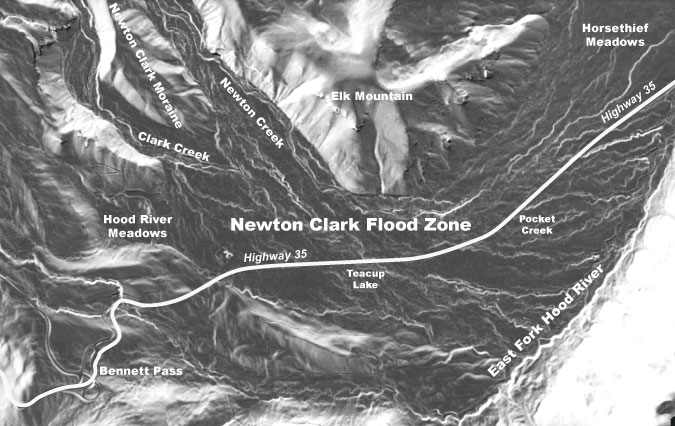

We can see this ancient story playing out in new LIDAR imagery, a form of aerial radar used to map the earth’s surface in stunning detail, revealing landforms that could never be captured with conventional surveying. Over the past decade, the Oregon LIDAR Consortium has been working to bring this new mapping technology to a larger audience, including for the Mount Hood area. LIDAR has allowed geoscientists to map the history of faults, floodplains and landslides as never before.

The map below is from the Oregon LIDAR project, and shows how Newton and Clark creeks emerge from their narrow, twin mountain canyons to spread out on the floor of the broad East Fork Hood River valley. The valley floor is made up of loose debris deposited from these floods over the millennia, and both Newton and Clark creeks have changed course in this soft material with regularity.

(Click here for a larger view of the Newton Clark Flood Zone map)

You can see this history in the maze of braided channels that show up on LIDAR. Whereas topographic maps simply show a relatively flat, featureless valley floor here, LIDAR reveals hundreds of interwoven flood channels across what we now know as the Newton Clark flood zone.

Many of these channels were formed centuries ago, and some in our lifetimes. Some may have flowed for decades without much change, while others may have formed in a single event, then went dry. Both Newton and Clark creeks are continually on the move, and so long as the main steam of the East Fork is on the opposite, and downhill side the Mount Hood Loop Highway (OR 35), both streams will continue to wreak havoc on the highway.

In 2012 the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and ODOT replaced the bridge at White River and built massive new culverts for Clark and Newton Creeks on the east side of the mountain (below).

The following are a few photos taken after the water subsided in the fall of 2006, and ODOT crews were assessing the damage to OR 35. The damage shown here occurred over a 24-hour span.

So far, the new flood structures at Newton Creek have not been tested by a major flood event. But when you consider the mosaic of old stream channels in the LIDAR imagery that have been created over the centuries by hundreds of flood events, these new structures are temporary, at best. It’s only a matter of time.

____________________

I’ve mentioned several hikes in this part of the article, and they can also be found in much more detail in the Oregon Hikers Field Guide at the links below. Enjoy!

Gnarl Ridge from Hood River Meadows Hike

Gnarl Ridge from Cloud Cap Hike

____________________

Special thanks to the Hood River History Museum for permission to include photos from their outstanding collection of historic images in this article. Like all museums, they are closed to the public until further notice because of the COVID-19 pandemic. This has an immediate impact on funding their operations, so please consider supporting the museum during this crisis with a donation. You can make one-time or ongoing monthly donations via PayPal, just go to the “donate” link on their website to support their valuable work.

And another special thanks to Oregon Hikers off-trail legend Chip Down for permission to use his photo of the Newton Clark Prow, one of the least-explored places on Mount Hood. You can read his trip report and see more of his outstanding photos of the Newton Clark backcountry over here.

______________

Postscript:this article was two years in the making (!), as the story of Newton Clark is told in bits and pieces in century-old sources. Despite the miracle of the internet and the astonishing information we have at our fingertips in our time, uncovering local history is still like peeling back the layers of an onion. With each new discovery, more mysteries are uncovered… and blog articles get a bit longer and a bit later!

In this spirit, please help me improve this short history of Newton and Mary Clark and their family where I’ve made errors or omissions.

Thanks for stopping by and reading this especially long entry!

Tom Kloster | May 2020