In the span of just about a decade, the Oneonta Tunnel on the Historic Columbia River Highway (HCRH) has endured a wild ride. The tunnel had been closed since the 1940s when the old highway was rerouted around the cliffs of Oneonta Bluff, and for more than half a century lived only in memories and photographs.

Then, the tunnel was carefully restored to its original glory in 2006 as part of the ongoing effort to restore and reconnect the HCRH. But within just few years, the beautiful restoration work was badly vandalized by uncontrolled mobs of thoughtless young people unleashed upon Oneonta Gorge by social media (see “Let’s Clear the Logjam at Oneonta Gorge). Then, in September 2017, the restored timber lining was completely burned away during the Eagle Creek Fire.

Today, the tunnel stands empty and fenced-off, waiting to be brought back to life, once again. But does it make sense to restore it as before, only to set this historic gem up for more vandalism? Or could it be restored in a different way, as part of a larger vision for protecting the history and natural beauty of both the tunnel and Oneonta Gorge, while also telling the story of the scenic highway, itself? More on that idea in a moment…

First, a look at how we got here.

Before the dams and after the railroads…

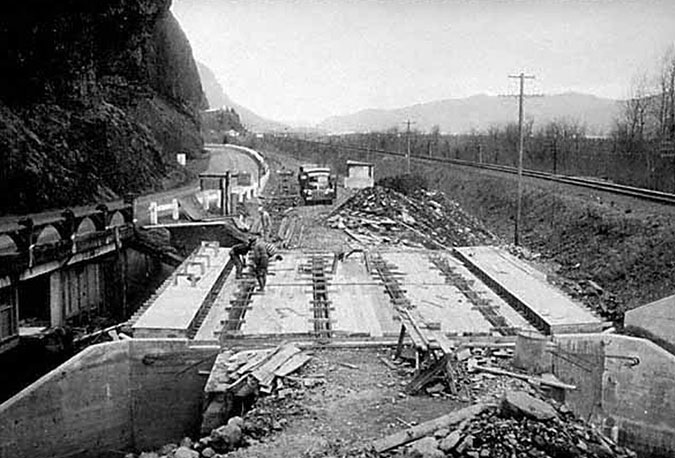

Looking at Oneonta Tunnel today, it’s hard to understand why the original highway alignment went through Oneonta Bluff to begin with, instead of simply going around it? Why wasn’t it simply built in the current alignment of the historic highway, which curves around the bluff? The answer can be seen in this photo (below) taken before the old highway was built.

It turns out the original railroad alignment crossed Oneonta Creek on a trestle where the current highway is located today, and was also built snug against the base of Oneonta Bluff. Why was it built this way? Because in the era before Bonneville and Grand Coulee dams were completed in the 1930s (along with the many dams in the Columbia basin that followed), the Columbia River fluctuated wildly during spring runoff. So, the original rail line was built to stand above seasonal flood levels of the time.

When Samuel Lancaster assessed the situation in the 1910s, the only options for his new highway were to move the railroad or tunnel through the bluff. As with other spots in the Gorge where the railroads were an obstacle for the new highway, the second option turned out to be the most expedient, and the Oneonta Tunnel was born.

This close-up look (below) at previous photo shows a man standing on the railroad trestle crossing Oneonta Creek, pointing to what would soon be the west portal to the new tunnel, and I believe this to be Samuel Lancaster on a survey trip — though that’s just my speculation.

When the original alignment of the old highway opened in 1916, the new road paralleled the old railroad grade closely, especially east of the tunnel (below), where a retaining wall and wood guardrail separated the somewhat taller road grade from the railroad.

Sometime after the original tunnel was built, possibly in the 1930s, the railroad was moved away from the bluff, perhaps because of falling debris from the Oneonta Bluff landing on the tracks, or maybe just part of modernizing the rail line over time. The flood control provided by dams on the Columbia River beginning in the 1930s (and especially the relatively stable “pool” created behind Bonneville Dam) allowed the railroads to move several sections of their tracks in the Gorge onto extensive rock fill during this period, often well into the river, itself.

This photo (below) from the 1930s shows the west portal of Oneonta Tunnel after the railroad had been move northward, away from Oneonta Bluff, but before the highway had been realigned to bypass the tunnel.

The tunnel at Oneonta Bluff was one of several along the old highway, though it was easily overshadowed as an attraction by the famous “tunnel with windows” at Mitchell Point, to the east and the spectacular “twin tunnels” near Mosier. What made Oneonta Tunnel famous was the view into impossibly narrow Oneonta Gorge, which suddenly appears as you approach the west portal.

Oneonta Gorge has been a popular tourist attraction since the old highway opened in 1916. For nearly a century, adventurers have waded up the creek to the graceful 120-foot waterfall that falls into Oneonta Gorge, about a mile from the historic highway bridge. Only in recent years has overcrowding presented a serious threat to both the unique cliff ecosystem and the historic highway features here.

In the 1930 and 1940s, the Oregon Highway Department began a series of projects in the Gorge aimed at “modernizing” the old highway as the dawn of the 1950s freeway-building loomed. A new river-level route was built to bypass the steep climb the original route takes over Crown Point, with the new route following what is today’s I-84 alignment.

At Tooth Rock (above Bonneville Dam) a new tunnel was blasted through the cliffs to bypass the intricate viaducts built atop the cliffs by Samuel Lancaster. That tunnel still serves eastbound I-84 today, and has become a historic feature in its own right. And at Oneonta Bluff, a new bridge and tunnel bypass (below) took advantage of the relocated railroad, and was completed in 1948.

When the new bridge and realigned highway section opened, the original bridge Samuel Lancaster built at Oneonta Creek was left in place, thankfully, and it survives today as a elegant viewpoint into Oneonta Gorge and gateway to the tunnel. The Oneonta Tunnel was also decommissioned at the time, with fill at both entrances (below). The tunnel remained this way for the next half-century, as a curiosity for history buffs but forgotten by most.

The rebirth of Oneonta Tunnel began with a bold vision for restoring and reconnecting the surviving sections of the Historic Columbia River Highway as part of the landmark 1986 Columbia River National Scenic Area act, with this simple language:

16 U.S.C. 544j Section 12. Old Columbia River Highway: The Oregon Department of Transportation shall, in consultation with the Secretary and the Commission, the State of Oregon and the counties and cities in which the Old Columbia River Highway is located, prepare a program and undertake efforts to preserve and restore the continuity and historic integrity of the remaining segments of the Old Columbia River Highway for public use as a Historic Road, including recreation trails to connect intact and usable segments.

And so began what will eventually be a four-decade effort to restore the old highway to its original grandeur, with many beautiful new segments designed as if Samuel Lancaster were still here overseeing the project. Work began elsewhere on the old route in the 1980s, but eventually came to the Oneonta Tunnel in 2006 (below).

The restoration began with simply excavating the old tunnel, and later rebuilding the stone portals at both ends and installing cedar sheathing to line the interior. A new visitor’s parking area was created outside the east portal and the original white, wooden guardrails were also recreated.

For the next few years, the restored tunnel stood as a remarkable tribute to the work of Samuel Lancaster and our commitment to preserving the history of the Gorge. It was a popular stop for visitors and also served as fun part of a hiking loop linking the Horsetail and Oneonta trails.

Vandalism & Oneonta Gorge

Every new technology brings unintended consequences, and the advent of social media over the past two decades has been undeniably hard on our public lands. Where visitors once studied printed field guides and maps to plan their adventures, today’s decisions are more often based on a photo posted in some Facebook group or on Instagram, where hundreds will see it as the place to be right now.

This has resulted in the “Instagram Effect”, where huge surges in visits follow social media posts, both in the immediate near-term for a given place, and in the long-term interest in hiking and the outdoors. According to a 2017 study by Nielsen Scarborough, hiking in the Pacific Northwest has nearly doubled in popularity the past ten years, with Portland and Seattle ranking second and third (in that order) in the nation for number of hiking enthusiasts — Salt Lake City took the top spot.

Overall, that’s very good news for our society because hiking and spending time outdoors are good for all of us, and we live in a part of the world where we have some of the most spectacular places to be found anywhere in our own backyard. But the immediate effect of social media can often spell bad news when hordes of ill-equipped and ill-informed people descend upon a place that is trending on their phone.

Oneonta Gorge is one of the special places that fell victim to the Instagram Effect, with huge crowds of young people overwhelming the canyon on summer days over the past decade. Sadly, the Forest Service did absolutely nothing to curb the invasion, despite the obvious threat to the rare ecosystem here, and hazardous conditions presented by the infamous log-jam that has blocked the entrance to the canyon since the late 1990s (see “Let’s Clear the Logjam at Oneonta Gorge).

And another unfortunate casualty of this unmanaged overcrowding was the Oneonta Tunnel, itself, when the Oneonta Gorge mobs stopped by to record themselves for posterity in the soft, brand-new cedar walls of the restored tunnel (below). While the vandalism was maddening, the lack of any sort of public response from the Forest Service or ODOT to stem the tide was equally frustrating.

The vandalism didn’t stop with the destruction of the tunnel walls, however. The unmanaged crowds also tagged spots throughout the area with graffiti, and damaged some of the priceless historic features (below) left for us by Samuel Lancaster.

As discouraging as the damage at Oneonta was, it was also completely predictable. The idea of limiting access to popular spots in the Gorge is one that the public land managers at the state and federal level have been loath to consider, even when overuse is clearly harming the land and our recreation infrastructure. The problem is made worse by the crazy quilt of intertwined state and federal lands in the Gorge, complicating efforts to manage access, even if the will existed.

Then the fire happened in September 2017, changing everything…

The Fire

When the Eagle Creek Fire was ignited on Labor Day weekend in 2017 by a careless firework tossed from a cliff, few imagined that it would ultimately spread to burn a 25-mile swath of the Oregon side of the Gorge, from Shepperd’s Dell on the west to the slopes of Mount Defiance on the east. In the aftermath, the entire burn zone was closed to the public, and much of it still is. While the fire closure put enormous pressure on the few trails that remained open, it also opened the door to rethinking how we access to trails within the burn zone when they are reopened. How and when that happens remains to be seen.

At Oneonta Bluff, the images of the fire were dramatic and unexpected: the inferno spread to the interior of the restored tunnel and lit up the wood lining, completely burning it away like lit fuse. Local news affiliate KPTV published these views (below) taken by fire crews as the tunnel burned.

The Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) spent the weeks after the fire in 2017 assessing the damage to the historic highway, including these photos of the burned-out tunnel (below).

Today, the scene at Oneonta Tunnel hasn’t changed that much. ODOT eventually stripped the remaining, charred timbers from the tunnel and fenced off both portals to the public (below), though vandals have since pushed the fencing aside. The area remains closed indefinitely.

Though it might be heresy to admit, my immediate reaction when I saw the images of the burning tunnel in 2017 was relief. There was no end in sight to the social-media driven vandalism, and the interior had pretty much been ruined at that point, so the fire presented an unexpected opportunity for a redo, someday. Quite literally, it’s an opportunity for Oneonta Tunnel to rise from the ashes, but perhaps in a new way this time.

Remembering what we lost

A new vision for restoring Oneonta Tunnel — and protecting Oneonta Gorge — begins with remembering the fine restoration work completed in 2006. What follows is a look back at what that looked like, before social media took its toll.

At the west portal to the tunnel (where the original Oneonta Bridge, with its graceful arched railings, still stands), the restoration included a gateway sign, restored, painted guardrails built in the style of the original highway and an interpretive display near the tunnel entrance (below). The design functioned as a wide, paved trail, with the idea that cyclists touring the historic highway would pull off the main road and ride through the short tunnel section on a path closed to cars.

From the original highway bridge over Oneonta Creek, the view extended into Oneonta Gorge, but also down to this fanciful stairway (below) right out of a Tolkien novel. This feature of the original historic highway continues to take visitors down to the banks of Oneonta Creek (the landing Newell in the bottom center of the photo, at the base of the stairs, is the one broken by vandals in an earlier photo). Just out of view at the top of the stairs is a picturesque bench built into the mossy cliff.

The west portal restoration included new stonework around the timber frame that closely matched the original design (below).

Inside, the restored tunnel was lined with cedar plank walls and ceiling, supported by arched beams (below).

The east portal was similar to the west end of the tunnel, with stone masonry trim supporting the portal timbers (below).

Like the west side, the east entrance approach (below) was designed for cyclists to leave the highway and tour the tunnel and historic bridge before returning to the main road.

In practice, most of the traffic in the tunnel before the fire came from hikers and curious visitors parking on the east and west sides and walking the path to the viewpoint into Oneonta Gorge. This is partly because bicycle touring in the Gorge focuses on the extensive car-free-sections of the historic highway, though the shared-road portions of the old highway are expected to see continued growth in cycling as the entirety of the old route is fully restored.

A Fresh Start (and Vision)

The 2006 restoration of Oneonta Tunnel and its approaches was based on the idea of it simply serving as a bicycle and pedestrian path as part of the larger historic highway restoration project. But the tragic defacing of the newly restored tunnel is a painful reminder that it’s simply not safe to assume it will be respected if left open to the public, unprotected, as it was before. Even gates are not enough, as vandals have since demonstrated by tearing open the temporary fencing on the burned-out tunnel.

But what if we considered the tunnel and its paved approaches, including the historic highway bridge, as a useful space instead of a path? The tunnel is surprisingly wide, at 20 feet, and 125 feet long. That’s 2,500 feet of interior space! What if the tunnel were restored this time with the idea of using this as interior space? As a history museum, in fact? With the paved approaches as plazas with outdoor seating, tables and bike parking?

Though it’s not a perfect comparison, there is an excellent model to look to in southern Utah, just east of the town of Kanab, where the privately operated Moqui Cave Natural History Museum is built inside a sandstone cave. The cave was once a speakeasy, then a dance hall in the 1930s, before it was finally converted to become a museum in the 1040s.

While passing through Kanab on a recent road trip, the stonework blending with the standstone cave entrance at Moqui Cave (below) reminded me of the restored stonework at Oneonta tunnel portals, and how the entrances to the tunnel might be enclosed to create a museum space at Oneonta.

Like our Oneonta Tunnel, Moqai Cave is mostly linear in shape (below), with displays of ancient Puebloan artifacts and fossil dinosaur tracks displayed along its sandstone walls.

These section of the Moqui Cave are roughly the same width and height of the Oneonta Tunnel, with plenty of room for both displays and walking space.

Other solutions for enclosing the entrance at Oneonta Tunnel could draw from our own Timberline Lodge, on Mount Hood. While the stone foundation for the lodge is man-made, it’s not unlike the basalt portals at Oneonta. This is the familiar main entrance on the south side of the lodge (below), showing how the massive wood entry doors are built into the arched stone lodge foundation.

About ten years ago, another entrance to Timberline Lodge was handsomely renovated (below) to become barrier-free, yet still the massive, rugged lodge style that was pioneered here. This updated design shows how modern accessibility requirements could be met at an enclosed Oneonta Tunnel.

There are other examples for enclosing Oneonta Tunnel as a museum space, too. While it would be a departure from Samuel Lancaster original purpose and design to enclose the tunnel, I suspect he would approve, given how the Gorge has changed in the century since he built the original highway.

There are logistics questions, of course. Is the Oneonta Tunnel weatherproof? If the dry floors during winter the months after the 2006 renovation are any indication, than yes, having 150 feet of solid basalt above you provides good weather proofing! Does the tunnel have power? Not yet, but a power source is just across the highway along the railroad corridor. These are among the questions that would have to be answered before the tunnel could be used as a museum, but the potential is promising!

Getting a handle on parking…

One of the most vexing problems along the busy westerly section of the Historic Columbia River Highway is how to manage parking as a means for managing overall crowding. Today, parking is largely unmanaged in this part of the Gorge, which might sound great if you believe there is such a thing as “free parking” (there isn’t). But in practice, it has the opposite effect, with epic traffic jams on weekends and holidays, and travelers waiting wearily for their “free” spot at one of the waterfall pullouts.

At Oneonta, the lack of managed parking is at the heart of the destruction that mobs descending on Oneonta Gorge brought to the area, including the defacing of the tunnel. Some simple, proven parking management steps are essential, no matter what comes next at Oneonta. First, parking spaces must be marked, with a limited number of spots available and enforced. Can’t find a spot? Come back later, or better yet, at a less crowded time.

Second, the parking should be managed with time limits (30 minutes, 60 minutes and a some 120 minute spots for Oneonta Gorge explorers). Timed parking also allows for eventual parking fees during peak periods, which in turn, could help pay for badly-needed law enforcement in the Gorge. Eventually, it makes sense to meter all parking spots in the Gorge, but that’s going to take some a level of cooperation between ODOT, the Forest Service and Oregon State Parks that we haven’t seen before, so lots of work lies ahead on that front.

So, these are all basic tools of the trade for managing parking in urban areas, and the traffic in the Gorge is well beyond urban levels. It’s time to begin managing it with that reality in mind.

The east parking area (below) at the Oneonta Tunnel was rebuilt as part of the tunnel restoration in 2006, but is poorly designed, with a huge area dedicated to parallel parking.

However, this relatively new parking area includes a (rarely used) sidewalk, and thus it could be striped with angled spaces that would make for more efficient parking and also include space for a tour bus pullout. ODOT would just need to take a deep breath, since this would involve visitors backing into the travel lane when exiting a spot — a bugaboo for old-school highway engineers. But drivers manage this all time in the city. We can handle it.

The west parking area (below) at Oneonta is an unfortunate free-for all, with an unmanaged shoulder that was ground zero for the huge social media crowds that began clogging Oneonta Gorge in the late 2000s. This area needs a limited number of marked, timed parking spots no matter what happens at Oneonta in the future. There’s also plenty of room for a sidewalk or marked path in front of the parking spaces, along the foot of the cliffs, similar to the new sidewalk built east of the tunnel. This would make for much safer circulation of pedestrians here.

The west parking area would also be the best place for accessible parking spaces, since it offers the shortest, easiest access to the tunnel and views of Oneonta Gorge from the historic bridge.

Looking west for inspiration… and operations?

Most who visit the iconic Vista House at Crown Point don’t know that the interpretive museum inside the building is operated as a partnership between the non-profit Friends of Vista House and Oregon State Parks.

The Friends formed in 1982, well before the Columbia River Gorge Scenic Area was created in 1986, and have done a remarkable job bringing the Vista House back from a serious backlog of needed repairs. Today, it is among the jewels that draw visitors to the Gorge.

In their partnership with State Parks, the Friends operate a museum inside Vista House, as well as a gift shop and espresso bar in the lower level. Proceeds from the gift shop are directed to their ongoing efforts to preserve and interpret this structure for future generations.

The unique partnership between the Friends of Vista House and Oregon State Parks is a proven, successful model, and it could be a foundation for a museum in the restored Oneonta Tunnel. Could the Friends operate a similar facility at Oneonta as part of an expanded mission? Perhaps. Or perhaps another non-profit could be formed as a steward for the tunnel, in partnership with the U.S. Forest Service and State Parks?

Crucially, having a staffed presence at Oneonta would allow for effectively managing access to Oneonta Gorge, itself, using a timed entry permit system. This is a proven approach to protecting vulnerable natural areas from overuse, and the Forest Service already uses timed permits elsewhere. Ideally, this permitting function would be funded by the Forest Service, and would include interpretive services for other visitors discovering the area, as well.

Focus on Sam Lancaster’s Road?

On the cut stone wall of the Vista House, a bronze plaque honoring Samuel Lancaster provides a very brief introduction to the man. Displays inside Vista House, and elsewhere in the Gorge, also tell his story in shorthand. But Lancaster’s original vision and continued legacy in shaping how we experience the Gorge deserves a more prominent place. A converted Oneonta Tunnel Museum would be a perfect place to tell that story.

The walls of the tunnel provide a combined 250 feet of display space, which could allow visitors to have a detailed look at some of the secrets of Sam Lancaster’s amazing road. The State of Oregon has a rich archive of historical photos of the highway during its construction phase, mostly unseen by the public for lack of a venue.

These include rare photos of spectacular structures now lost to time. Among these (below) is the soaring bridge at McCord Creek, destroyed to make room for the modern freeway, and the beautiful arched bridge at Hood River, replaced with a modern concrete slab in the 1980s.

A new Oneonta Tunnel Museum could tell the story of Sam Lancaster’s inspiration for the famous windowed tunnel at Mitchell Point (below), another lost treasure along the old highway destroyed by modern freeway construction.

A new museum at Oneonta could also tell the story of the surviving gems along the old road that are now part of the Historic Columbia River Highway State Trail. These include (below) the spectacular section between Hood River and Mosier, with its iconic twin tunnels, the beautifully crafted stone bridge at Eagle Creek and the graceful arched bridge at Shepperd’s Dell.

The story behind the building of the old highway extends beyond the genius of Samual Lancaster and the beauty of the design. The construction, itself, was a monumental undertaking, and the stories of the people who built this road deserve to be told in a lasting way for future generations.

The Lancaster story continues today, as well. Since the 1980s, ODOT, Oregon State Parks and scores of dedicated volunteers have steered the ongoing effort to restore and reconnect the old route, as called for when the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area Actwas signed into law in 1986.

Many of the restoration projects are epic achievements in their own right, and deserve to have their story told for future generations to appreciate. All are inspired in some way by Samuel Lancaster’s original vision for a road blended seamlessly into the Gorge landscape in way that allows visitors to fully immerse themselves in the scenery. These include handsome new bridges (below) at Warren Creek and McCord Creek, as well as a planned recreation of the Mitchell Pont Tunnel.

What would it take to create an Oneonta Tunnel Museum dedicated to Samuel Lancaster’s enduring vision? Capital funding, of course, but that will surely come at some point, given the current state of the tunnel after the fire. It would also take a willing non-profit partner and a strong interest from the Forest Service, ODOT and Oregon State Parks to try something different when it comes time to once again restore the tunnel. But the time to start that conversation is now, before the agencies start down the path of simply repeating mistakes from the past decade.

So, for now, this is just an idea. But in the meantime, if you’d like to learn more about Samuel Lancaster and his amazing highway, there are two books that should be in every Gorge-lover’s library. And they make for especially good reading in this time in which we’re not able to visit the Gorge!

The first is Samuel Lancaster’s own book, The Columbia: America’s Great Highway, first published in 1916 by Lancaster, himself. This book is as eccentric and sweeping as Lancaster’s own imagination, and his love for the Gorge comes through in his detailed descriptions of the natural and human history. It’s easy to see how his vision for “designing with nature” grew from his intense interest in the natural landscape of the Gorge.

Lancaster’s original book was reproduced in 2004 by Schiffer as a modern edition, and is still in print. The modern version includes restored, full-color plates from the 1916 edition, as well as additional plates that were added to a 1926 version by Sam Lancaster.

A wonderful bookend to Sam Lancaster’s classic is Building the Columbia River Highway: They Said it Couldn’t Be Done by Oregon author Peg Willis. This exceptional book focuses on the highway, itself, and the collection of characters who came together to make Samuel Lancaster’s bold vision become reality.

Peg’s book also includes a terrific selection of seldom-seen historic photos of the highway during it’s original construction, reproduced with fine quality. In fact, the stories and images in this book would a perfect blueprint for the future Oneonta Tunnel Museum… someday!

_________________

As always, thanks for stopping by and reading through yet another long-form article in our era of tweets and soundbites!

Special thanks to Oregon photographer TJ Thorne, who contributed photos of the Oneonta Gorge summer crowds for this article. Those were just a few snapshots from his iPhone, but please visit TJ’s website to see his amazing fine art nature photography from landscapes across the American West, and please consider supporting his work.

Oregon’s outdoor photographers serve as our eyes on the forest, taking us places we might otherwise never see. They help the rest of us better appreciate and protect our public lands through their dedicated work, but they need our support to continue their work.

Thanks, TJ!

_________________

Tom Kloster • April 2020

Hi Tom:

We met several years ago at a series of meetings in Cascade Locks (i was on the board of FOCG at the time). At any rate, just want you to know how much I enjoy your blogs–always thoughtful, informative, interesting, and well written. Plus you always find terrific photos. I often post your entries on the fb page for my hiking group and they enjoy them as well.

Just wanted you to know that you have a bunch of fans out there who appreciate your effort.

debbie asakawa

________________________________

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Tom Kloster, for yet another excellent history of what we all treasure in the Gorge. I first met you in 2015 when you led a small group of FOCG enthusiasts up to Lancaster and Warren Falls. All of us admire and appreciate your blog. — Gunnar Sedleniek, Lake Oswego

/Users/gunnersedleniek/Pictures/My Pictures/My Pictures/My Pictures 2/StarvationCreek.jpg

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Debbie and Gunnar! Debbie, I remember you well — thanks for your outstanding service on the Gorge Friends Board. I currently serve on a non-profit board, and I know it’s a labor of love! 🙂 Gunnar, I remember you, as well — those were fun hikes, and I’m hoping to lead more once the Gorge reopens! See you both on the trail! 🙂

LikeLike

What a vision! How hopeful! Troutdale Historical Society and Crown Point Country Historical Society would also be wonderful assets in the quest to create an enclosed museum for the Tunnel. Lancaster and the Highway would be perfect subjects. Thank you for your imagination and ability to look beyond the loss toward possibilities.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Claudia! Appreciate you stopping by! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love your entries; amazing as always! I’m probably one of the few young people to frequent this blog, and I’m with you that something needs to be done for long-term management in the CRGNSA, particularly at Oneonta Gorge. Do you think a daily quota of people allowed in the Oneonta Gorge (say, 100 per day) would be a feasible solution? It will be interesting to see what the area is like in 50 years, when I’m in my 70s.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Tom,

I always enjoy your WyEast blogs. Thanks.

I tried to order the book from Schiffler. I stopped when I discovered that the shipping was nearly the cost of the book itself at $20.41.

-Regis

LikeLiked by 2 people

Wow, thanks for the heads-up, Regis! A better plan would be to support our local Powells.com, of course!

Brian, thanks for stopping by! Yes, a limited number of daily permits is totally feasible (the USFS already does that in several spots, and the National Park Services does this in many places that could be harmed by overuse). The key is really just an agency will to do so — and that means enforcing the permits. But the advantage of Oneonta is that there’s just one way in and one way out… (without ropes) 😉

That said, I think it’s going to be unsafe to let anyone go in there for awhile, as the logs from the Eagle Creek Fire are rapidly building up behind the existing log jam, and will make it truly impassable to get through without getting hurt.

Tom

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Proposal: Oneonta Loop Trail | WyEast Blog