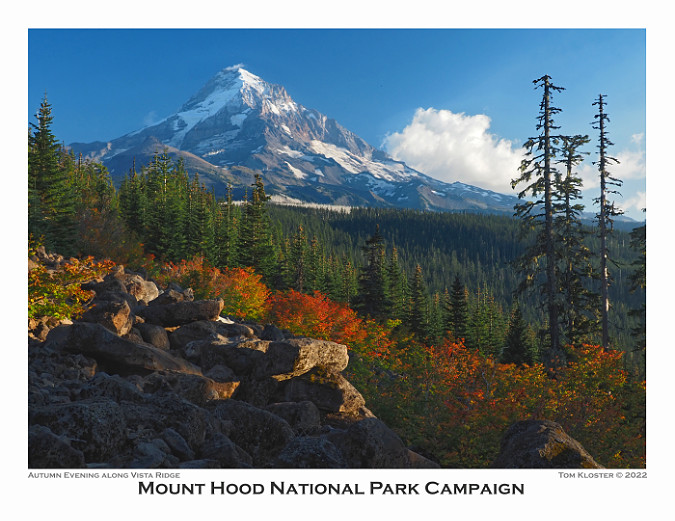

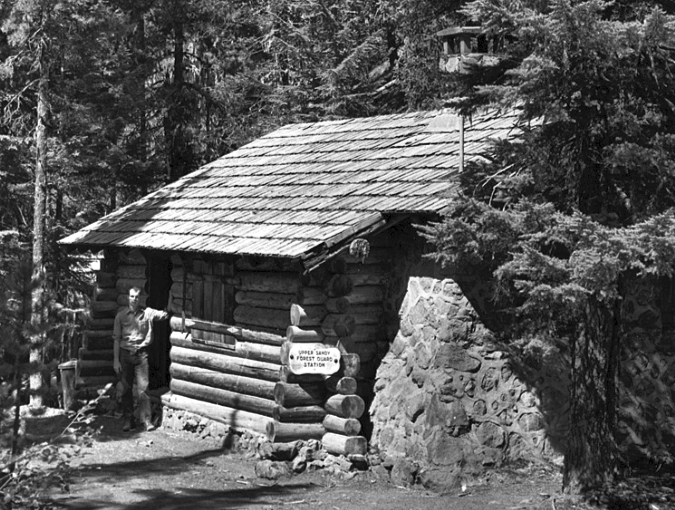

2025 Campaign Calendar Cover

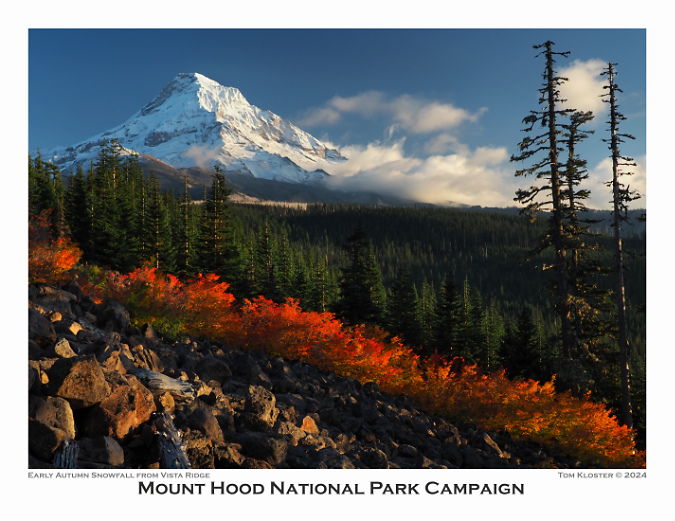

December brings my annual year in review as told through the images I’ve chosen for the new Mount Hood National Park Campaign calendar. It’s a collection of images from around WyEast country that captures my explorations over the past year and its published in a high-quality, oversized format by the good folks at Zazzle. You can order one here:

2025 Mount Hood National Park Campaign Calendar

As always, all proceeds go to Trailkeepers of Oregon (TKO) and you can have these calendars delivered anywhere. You may notice a Red Rock Country calendar of desert southwest images from a recent trip through the Colorado Plateau — proceeds from the is calendar to to TKO, as well! Meanwhile, here’s a deeper dive into the thirteen images I selected for this year’s calendar.

Stories behind the photos…

The cover image is also the most recent in the calendar. It’s an alpenglow view of Mount Hood’s west face taken from Lolo Pass road in early November. This is a classic spot for photography after the first few fall snowstorms, so I’m rarely alone there – a notably, I ran into Peter Marbach, one of our amazing WyEast Country professional photographers on this visit! This view came a few minutes before sunset on a crystal-clear fall evening:

Last light after an early snowfall on the mountain is the cover image of the 2025 campaign calendar

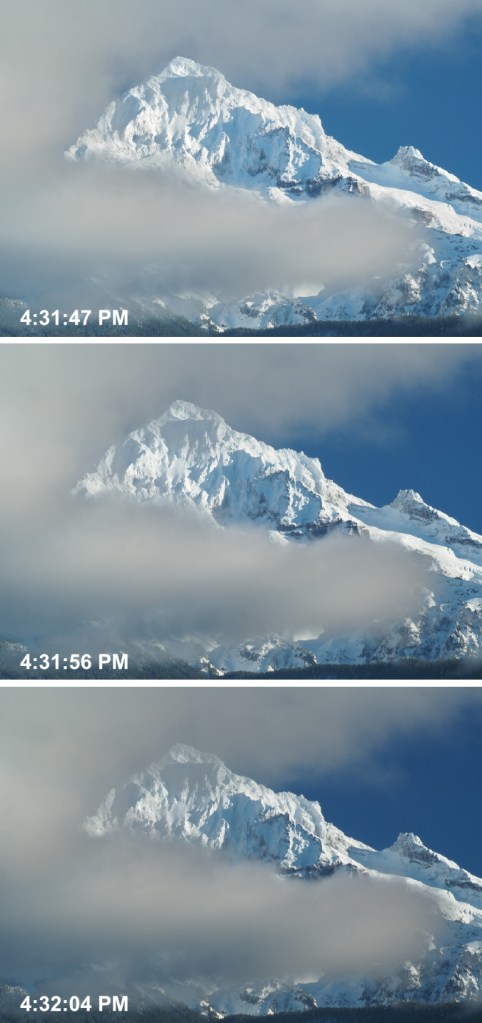

The backstory to this photo is that I had planned to shoot from a favorite spot on the east shoulder of Lolo Pass that evening. I even had my camera set up, ready to go, when a huge fog bank rolled up the West Fork Hood River valley and parked over me at Lolo Pass. It happened in less than a minute, as the photo sequence below shows:

Lolo Pass fog rolling in… setting up my tripod seems to have this effect on the weather!

It turns that topographic conditions are prime at Lolo Pass for fog events like this (sometimes becoming freezing fog). Most of these are triggered when colder, drier continental air from east of the Cascades collides with moist, marine air from west of the mountains to form very localized fog banks parked on top of the pass, with otherwise clear weather to the east and west.

Sure enough, when I packed up and headed to a viewpoint just west of the pass, the mountain was in full view – along with the fog bank draped over Lolo Pass (below). This is where I captured the cover photo for the new calendar that day and had the pleasure of meeting Mr. Marbach! I’m still kicking myself for not getting a selfie – I’m a big fan of his amazing work.

Looking back at the Lolo Pass fog bank from the west side of the mountain

In fall and early spring, strong temperature inversions can also fill the mountain valleys on both sides of Lolo Pass with dense fog. As the sun drops down toward sunset, the valley inversion fog often surges over the pass due to its remarkably low elevation of just 3,415 feet – at least a thousand feet lower than most of the Cascade passes in Oregon.

Continuing with the fog theme, inversion valley fog is just how this photo (below) I chose for January image in the new calendar came about. This scene was captured on the east side of Mount Hood, along the lower slopes of Lookout Mountain, with the East Fork Hood River canyon filled nearly to the brim with a dense, thousand-foot thick layer of fog. The view is framed with long-needled Ponderosa Pine boughs, the signature conifer species on the east slope of the Cascades.

More fog for the January calendar image – this time in the East Fork Hood River valley

Here’s a wider view from the same area (below) showing how the fog filled the valley like a bathtub that day, thanks to a layer of cold, moist air trapped by a stable high-pressure system that was bringing all that sunshine and relatively mild temperatures directly above. On winter days like this, it’s common for temperatures in the fog zone to be hovering near freezing while temperatures above the inversion rise well into the upper 40s or even low 50s.

East Fork Hood River inversion fog and Mount Hood

Inversion fog is common on the east end of the Columbia River Gorge and is tributary valleys in winter, often with freezing temperatures that make for spectacular frost displays (and slick roads) when the inversions persist. The forests here are completely adapted to this effect, including the annual pruning that a heavy ice accumulation from persistent fog can bring.

In this view (below), the winter advantage of Western Larch also stands out. While a few of the Larch still have their golden needles, most (like the one in the center) have already dropped their foliage for the winter, making them less susceptible to heavy winter winds and accumulations of snow and ice. Like Ponderosa Pine, Larch are also fire-resistant – making them perfectly adapted to this “fire forest” mountain ecosystem.

Fog swirling through an east side forest of Larch, true firs, Douglas fir and Ponderosa pine

The fog was sloshing around the East Fork valley that day as I watched and captured the changing scenes. While the overall inversion layer is generally flat, there are waves in the upper surface of the fog what wash “ashore” along the valley walls as the inversion air pressure gradient rolls across the surface of the fog layer. It’s mesmerizing to watch this effect from just above “shore level” as the waves surge below.

This final view was taken from the same spot as the above calendar image, and it shows an approaching wave of fog that would soon overtop the spot where I had set up my camera for these images. Once it engulfed me, the air temperature nearly 20 degrees in just a few minutes!

The mountain a few minutes before the ocean of fog inundated this spot!

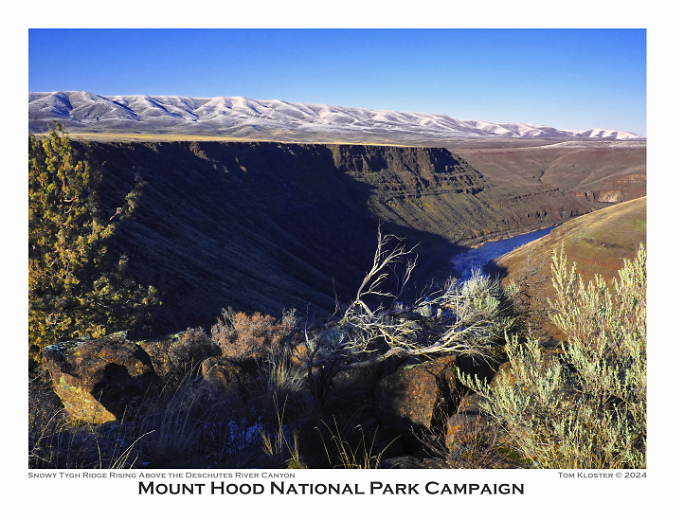

Winter can be long and grey on the west side of the mountains, but if you know Oregon’s weather patterns you can often spot conditions when the east side of the mountains will be bright and sunny, even as rain falls on the west side. A favorite retreat for me on these days is the lower Deschutes River Canyon, less than two hours from Portland.

Despite the still-cool temperatures, I prefer to visit the Deschutes River in late winter, when few people are there, and the canyon slopes are green with emerging spring growth and the Alders turn yellow, then rusty-red with catkins. For the February image in the new campaign calendar, I chose this scene (below) near Rattlesnake Canyon that features a picturesque White Alder just coming into its late winter bloom.

White Alder providing winter color along the Deschutes River for the February calendar image

Here’s another winter scene along the Deschutes with a mature grove of White Alder (below) growing along the riverbank. White Alder are not widespread in Oregon, and mostly limited to the Willamette Valley, eastern Columbia River Gorge (including the lower Deschutes Canyon) and the Siskiyous in Southern Oregon, Their range overlaps the Red Alder, its close cousin, that grows along the Pacific coast and extends as far inland as the Willamette Valley, where the two species meet.

White Alder (left) in winter along the Deschutes

Seen up close, both the male and female catkins of White Alder come into view. In this February photo (below), the male catkins are the long, pendulous blossoms and the green female catkins are still in bud form, just beginning to emerge. The “cones” of last year’s female catkins can still be seen, too. They are the dark ovals that resemble tiny pine cones when they open and dry to a dark brown color in fall. Because White Alder contains both male and female flowers on the same tree, they rely only on wind to pollinate, and the desert country east of Mount Hood provides plenty fo that!

White Alder catkins emerging in February

This view of a typical section of the Lower Deschutes canyon (below) shows just how important the White Alder groves that line the shore are to the ecosystem. They are the only sizable trees in this desert landscape, and they provide essential wildlife habitat along the river. Both Red and White Alder are also nitrogen-fixing trees, enriching the soil for other plants wherever they grow.

White Alder groves line the lower Deschutes River Canyon in winter

Another surprise on this winter trip to the Lower Deschutes were the many flowing tributary waterfalls that are dry for much of the year. This unnamed, two-tier waterfall near Trestle Bend is dropping into a grove of White Alder (below).

Season waterfall dropping into the Deschutes canyon in winter

While I’ve known for some time that Rocky Mountain Bighorn Sheep live in the Lower Deschutes canyon, I had not seen them until this trip last February, when I spotted two herds high above the river, just upstream from Rattlesnake Canyon. Both were bachelor herds working their way downstream, along the upper slopes of the canyon (below).

Bighorn Sheep in the lower Deschutes River canyon

Bighorn Sheep are a welcome sight in the Deschutes River canyon, not just because they’re beautiful to see and watch, but because they’re also an indicator of ecosystem health. Bighorns are highly sensitive to human activity, so their presence here reflects the continuing efforts by the Bureau of Land Management and Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife to expand habitat protection for these animals in Oregon’s desert country.

Bighorn Sheep in the lower Deschutes River canyon

This trip was my second to the Lower Deschutes last winter, and I did have a practical mission for returning. On the first trip I had come frighteningly close to dropping a wheel over the edge of a paved section of the river access road, where a landslide has taken a big bite out of it. When I pulled over to take a look, I was spooked by the realization that going off the road here would have sent me 200 feet down the landslide scar, and directly into the river!

So, one week later I came armed with a can of white paint to (at least temporarily) mark off a shy distance for drivers passing north along the road. Hopefully, the land managers didn’t mind…

Scary landslide damage to the Deschutes River Road!

This aerial view of the landslide scar from Google Earth (the image below is from 2022) shows just how sketchy the situation is, and that there are really two slides at work, here. The larger slide on the right is the one picture above, where the roadway has been seriously compromised.

Aerial view of the Deschutes River Road landslides in 2022 (Google Earth)

For the March calendar image, I moved to the Columbia River Gorge and Tanner Creek. It’s a place that I describe as the “Gorge on the half-shell”, as this spectacular 2-mile loop trail along to Wahclella Falls has all of the elements of a classic Gorge hike: towering basalt cliffs, a rushing stream with thundering waterfalls, wispy, impossibly tall tributary waterfalls, old-growth Douglas Fir and Western Redcedar, fern-covered talus slopes and lush green moss on seemingly every surface. Throw in four unique footbridges (one where you can reach out and touch a waterfall) and it’s a perfect introduction to the Gorge.

In past years, I have included a favorite scene captured from a viewpoint high above the falls, showing a couple of the tributary waterfalls dropping into the deep gorge that Tanner Creek has carved. I captured the scene once again this year (below), but wanted to try something different for 2025.

Wahclella Falls in the Columbia River Gorge

This year I opted for the view from in front of the falls (below), taken from the long footbridge that can spotted in the previous photo. From this streamside perspective, a young Western Redcedar growing directly in front of the falls, and will soon block the view. So, for this year I embraced the photo-bombing tree and framed it to be directly silhouetted by the falls while it’s still short enough not to completely block the view.

Wahclella Falls and the upstart Western Redcedar tree are featured as the March calendar image

How long before the tree eclipses the view from the footbridge? Here’s a comparative view of this young upstart, and you can see that it will clearly block the falls from this vantage point in the next decade or so… if it survives! That’s an open question, as this little tree is growing quite close to Tanner Creek, and there’s a reason the largest trees near the falls are on higher ground. Tanner Creek is big and rowdy in winter, and regularly scours the streambanks along its course in high water, easily carrying away whole trees in its wake. The giant logjam in the earlier, wide view of the falls is testament to the stream’s power.

The upstart cedar at Wahclella Falls

[click here for a much larger version]

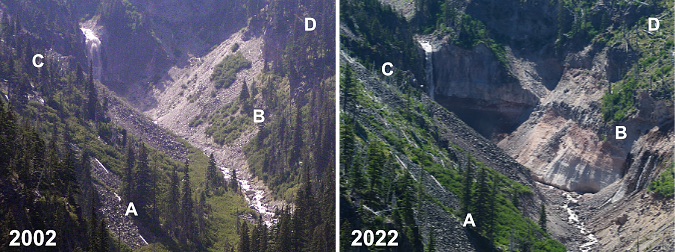

For geoscience types (that would be me), the still-fresh scar from the 1973 landslide at Tanner Creek is hard to take your eyes off when hiking this trail, but in recent years there have been a series of much smaller basalt wall collapses right next to Wahclella Falls that are fascinating to track. Sometime in the past year, another 15×20 foot slab immediately west of the falls collapsed into the splash pool after being undercut by erosion from the pounding water. The photo pair below shows the new scar.

Recent wall collapse along the Wahclella Falls splash pool

This latest evidence of the ongoing erosion along Tanner Creek is a more typical example of the incremental, nearly constant deepening of the canyon that occurs through the combination of gravity and annual freeze-thaw cycles that push cracks in the basalt walls open and gradually the rock apart.

This weaking of the rock is accelerated by the erosive action of Tanner Creek in undercutting the canyon walls, especially where the heavy basalt layers rests on the must softer Eagle Creek Formation, made up of ancient volcanic debris flows that are easily eroded by the stream. The trailside cave just below Wahclella Falls (where the new the new logjam has accumulated) is a great example of stream erosion cutting away this softer layer beneath several hundred feet of vertical basalt cliff, above. This was mostly likely what triggered the massive 1973 collapse, as well.

For the April image in the new calendar, I chose a scene that put April-blooming Balsamroot front and center. This view from the Columbia Hills State Historical Park (below) is looking west toward Mount Hood on a cool, blustery spring day.

Mount Hood and the flood-scoured lower slopes of the Columbia Gorge are featured in the April calendar image

Staying with a geology theme, this viewpoint is notable for how rocky this scene below is. It was taken at a point just below the high-water mark of the series of ice age floods that shaped much of what we know as the Gorge today. The floodwaters scoured away all but the most resistant basalt, leaving this rugged terrain we know today behind.

You can easily spot the high-water mark of the ice age floods in this part of the Gorge. Just a hundred feet uphill from the viewpoint where the previous photo was taken, the terrain suddenly softens into the rolling slopes that make up the Columbia Hills (below). There’s plenty of jagged basalt here, too, but it’s mostly buried under millennia of soil accumulation that survived the floods thanks to being mainly above the flood levels.

Gentle terrain above the ice age flood high-water level in the Columbia Hills

The surviving soil in these upper slopes of the Gorge translate into enormous wildflower meadows that draw people from around the world. Yellow Balsamroot steals the flower show in the east Gorge in spring, but in places with the Columbia Hills, they are just part of a wildflower spectacle, with Phlox (below), lupine and dozens of other wildflowers filling the gaps between the showy Balsamroot.

Spring wildflower gardens in the Columbia Hills

Each time I visit places the east Gorge in spring, I make it a goal to spot a few of these co-stars in the flower show that I might not have noticed before. To my surprise, my visit last spring included Ballhead Waterleaf, a lush plant that grows throughout the west, but is typically found in moist spots. Yet, this colony (below) had found a shady slope beneath a pair of Bigleaf Maple trees with just enough groundwater to help them thrive in this desert environment.

This Ballhead Waterleaf found a shaded niche in the Columbia Hills

Another striking wildflower was new to me on that trip, a lovely plant called Whitestem Frasera (below). It was just coming into bloom and still in bud when I was there, but in a couple weeks would have clusters of blue flowers rising above the beautiful foliage. This is one of many species that is typically found well east of the Cascades, but makes its way well into the Columbia River Gorge where conditions are right.

Whitestem Fraseria still in bud in the Columbia Hills

Still more surprising on that trip were several Cushion Fleabane (below) colonizing the old access road that forms the first mile or so of the Crawford Oaks trail in the Columbia Hills. These little plants thrive in fine gravels, and the old roadbed provides that for them, now that traffic is mostly limited to hiking boots.

Tiny Cushion Fleabane in the Columbia HIlls

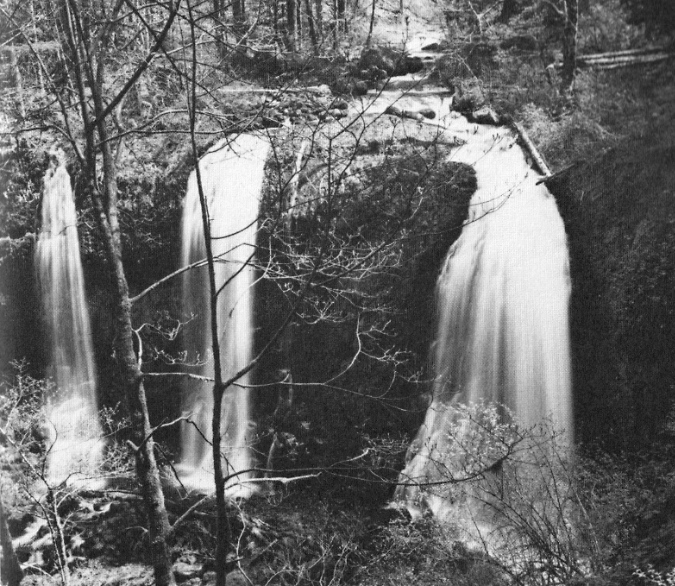

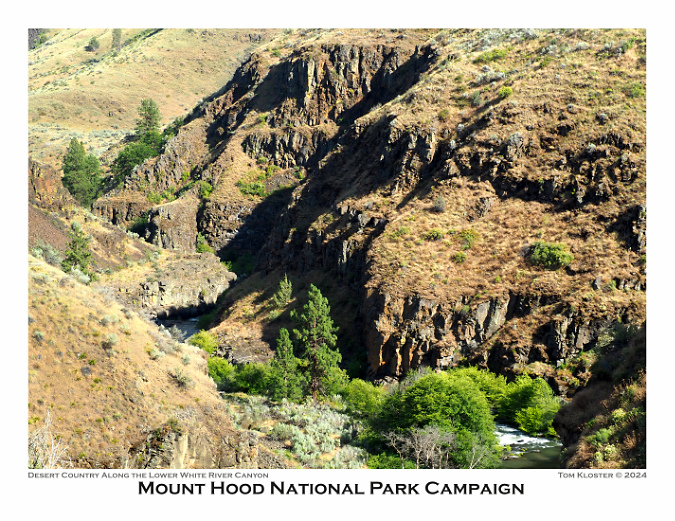

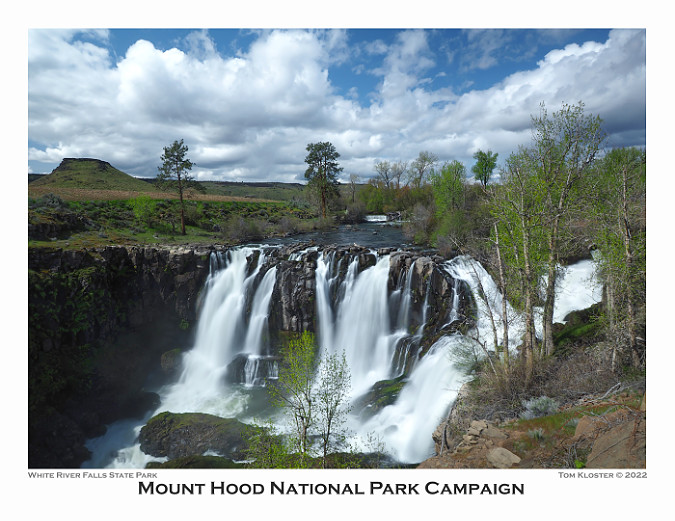

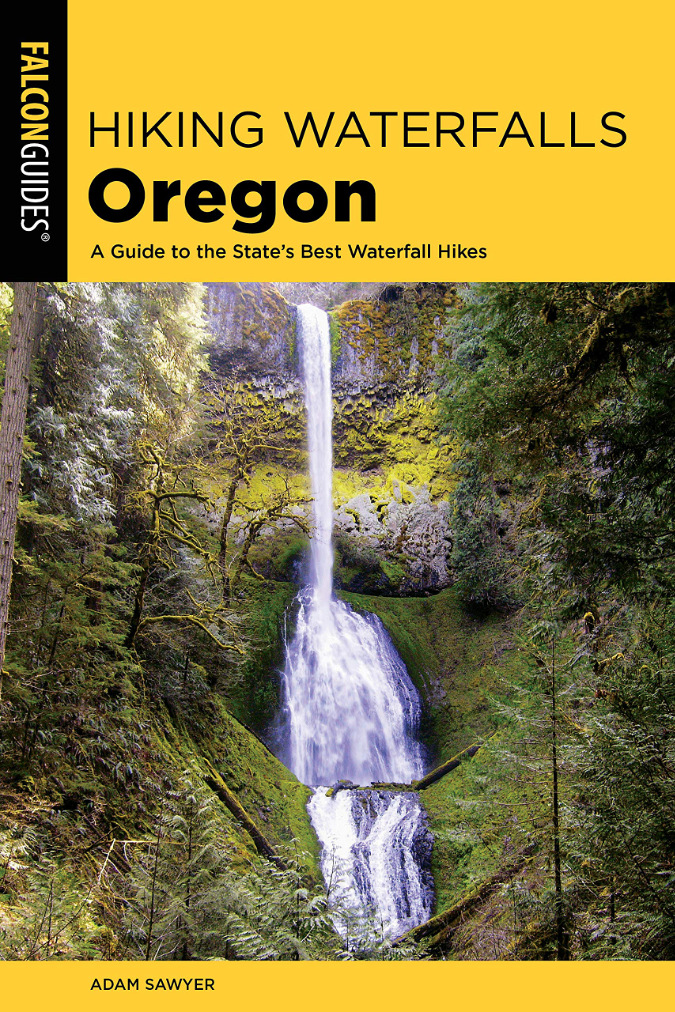

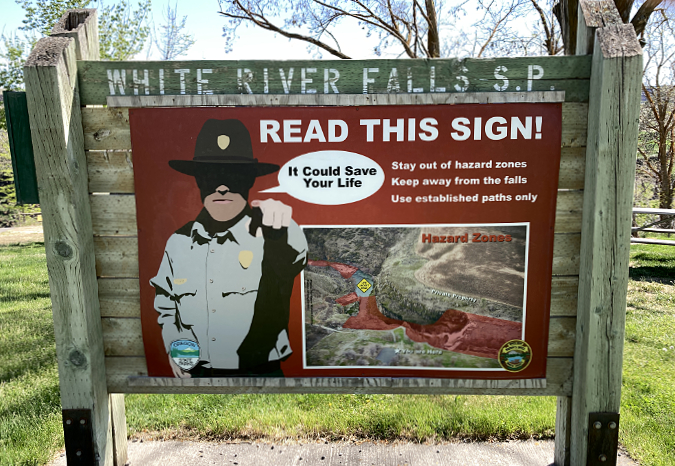

I stayed on the east side of the mountains for the May calendar image, with a view of White River Falls (below), where one of Mount Hood’s many glacial streams carves a deep canyon through sagebrush country and make a spectacular leap over a wide basalt cliff on the way to its confluence with the Deschutes River, just downstream. The falls and its lower canyon are protected as part of White River Falls State Park.

White River Falls during spring runoff in the May calendar image

This spectacular view of the main falls is best in spring, when runoff is high. The upper viewpoint is easily accessible, too – just a few hundred feet from the trailhead, with some of the path paved. But the deep gorge below the main falls hides still more waterfalls that make it well worth the steep hike into the canyon, despite the choppy descent along a long set of deteriorating stairs!

The stairway to White River heaven…

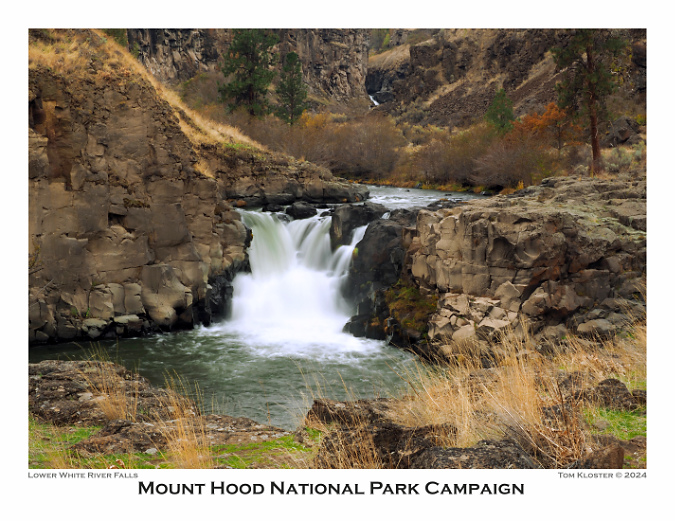

The lower tier of the main falls is unofficially called Celestial Falls (below) and forms a perfect punchbowl between walls of basalt. When winter temperatures drop below freezing, this natural bowl can become a mass of ice built up from the waterfall spray.

Celestial Falls on the White River, just below the main White River falls

Continue a bit further downstream on an increasingly unofficial trail, past the ruins of the early 1900s hydroelectric plant that once operated here, and the White River makes a third, smaller plunge into another, larger punchbowl at the lower falls (below). This might be my favorite spot in the canyon, as the lower falls and its deep pool are framed with wildflowers in spring, sprinkled among the boulders on the slopes that surround the river.

Lower White River Falls

There is a lot to see at White River Falls, and because it’s a regular stop for me, my eye goes to new details on each visit. When I stopped last spring and captured the calendar image shown previously, I was surprised to notice that beavers had taken up residence in the long, slow pool near the old powerhouse, between Celestial Falls and the lower falls. They had also recently made quick work of several trunks of a White Alder clump growing along the beach (below). If you look closely at the image from last April, you can see four fresh cuts, along with at least five previously cut trunks. Just one trunk remained, then, and even this sole survivor had a fresh scar where the beavers were working to finish the job on this grove!

Busy beavers at White River Falls State Park

In the more recent image from last month – just seven months later — you can see the Alder tree is fighting back with a vengeance. Not only did that lonely last trunk survive, dozens of new shoots exploded from the stumps over the summer to replace what the beavers had hauled away. It’s a great example of the continuous cycle between beavers and streamside trees.

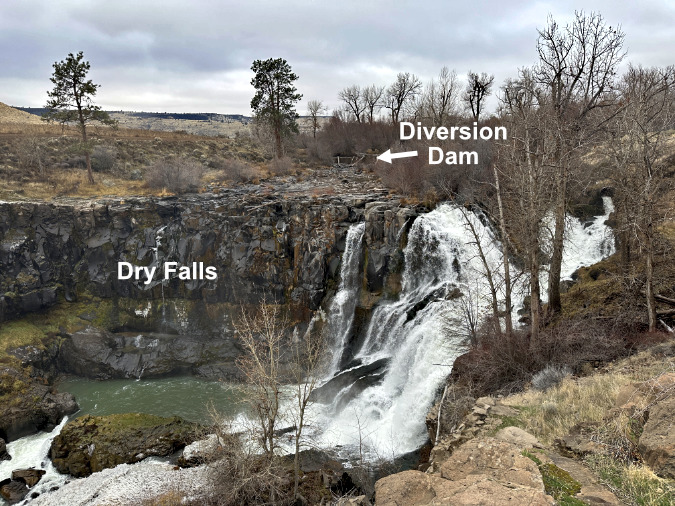

When I visited last month, I was also reminded of man’s impact on the falls. In low water, which extends from mid-summer into mid-winter, much of the face of White River Falls goes dry. Why? The answer is in the distance, just beyond the falls, where a long-derelict diversion dam (shown below) was built more than a century ago to direct water to the old hydroelectric penstock pipes.

Dried-up White River Falls in the low water season when the main river flow is diverted

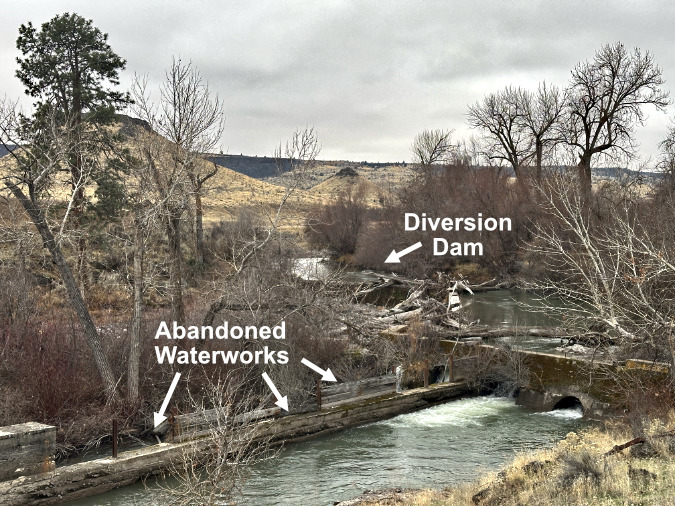

You can get a close-up look at the ruins of the old waterworks by following a path that heads upstream from the main falls overlook. Here, the diversion dam and abandoned canals that were once the headworks (below) to an elaborate pipe system are still diverting the river, but only to a side channel that spills around the main falls, as the pipe system was largely removed decades ago.

Derelict White River Falls diversion works depriving White River Falls its full spectacle

My hope is that Oregon State Parks officials will someday breach the old dam and restore the falls to its original channel year-round, instead of waiting for the White River to do the job (and it will, eventually).

For June, I chose another east-side image for the calendar. This view of Eightmile Falls (below) is where the main stream flowing from Columbia Hills State Historic Park drops over a basalt cliff as it enters the ice age flood-scoured lower reaches of the Columbia Gorge. In spring, this overlook is especially beautiful, lined with blooming Balsamroot and the creek is running strong with early season runoff.

June in the new calendar features Eightmile Falls in the Columbia Hills

Eightmile Falls is located along the Crawford Oaks trail, a relatively new access point to the park that follows a portion of the historic military road that once passed through this area. Along the way, there are views of Mount Hood and the Columbia River framed by old stone walls (below) from the early days of white settlement here in the late 1800s.

Stone walls in the Columbia Hills mark early white settlements in the area

One surprise along this section of the old military road is a grove of heritage apple trees that have somehow survived here for a century of more, in the middle of this harsh desert environment. In spring, they are covered with blossoms (below) that reveal them to be part of the human story here.

Heritage apple trees from white settlements still survive at Crawford Oaks

Another surprise along the old road are several groups of Bigleaf Maple, a species that thrives in Cascade rainforests. These unlikely trees manage to carve out a niche in this desert environment where they typically grows along basalt walls that provide both weather protection and provide groundwater seeps to help them survive hot summers.

Bigleaf Maple blossoms in the Columbia Hills

In spring, these out-of-place maples also put on an impressive flower display (above) that is easier to appreciate here, where the trees often grow just 15-20 feet high. Their foliage is at eye level, where you can see the blossoms close-up, compared to rainforest cousins where the blooms are often 70 or 80 feet above the forest floor.

For the July calendar image, I moved up into the mountains with this view (below) of the historic Cooper Spur Shelter, located along the Timberline Trail on the northeast shoulder of Mount Hood. This is among of the most iconic spots on the mountain, and it didn’t disappoint this year, with drifts of blooming yellow Buckwheat and purple Lupine framing the 1930s, Civilian Conservation Corps structure.

Cooper Spur Shelter with alpine wildflowers are featured in the July calendar image

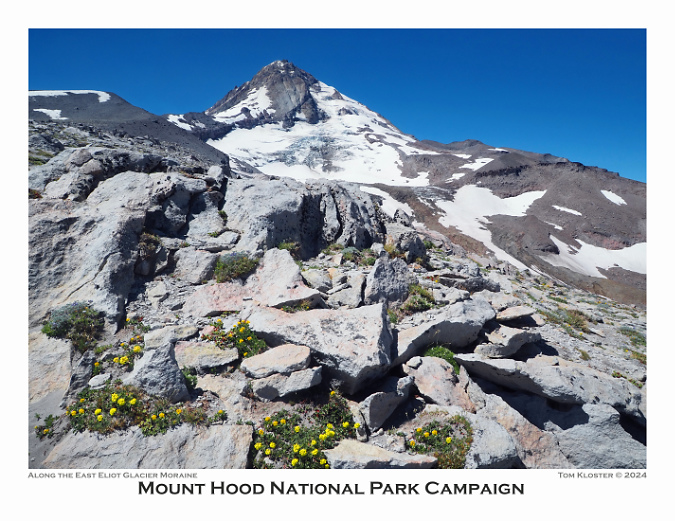

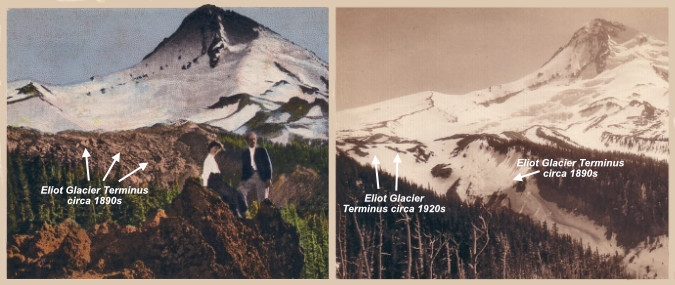

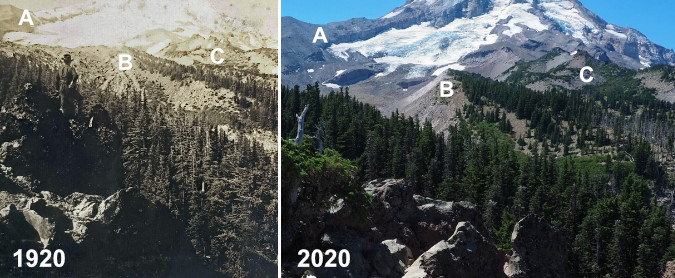

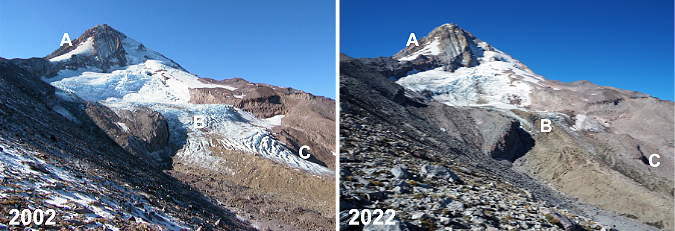

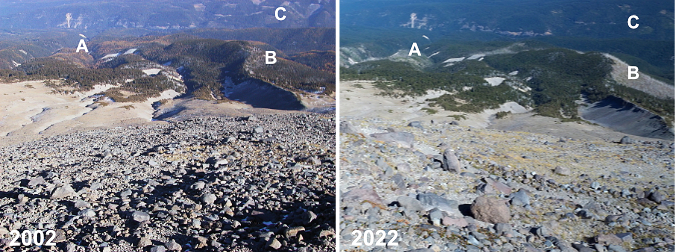

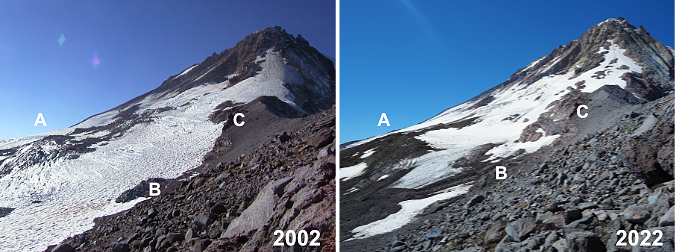

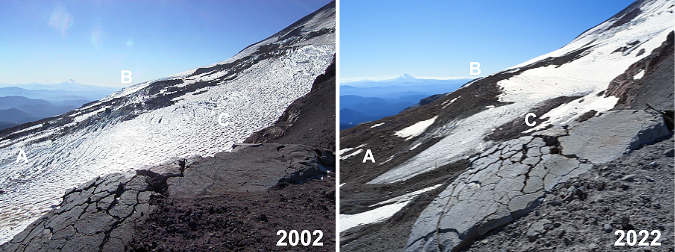

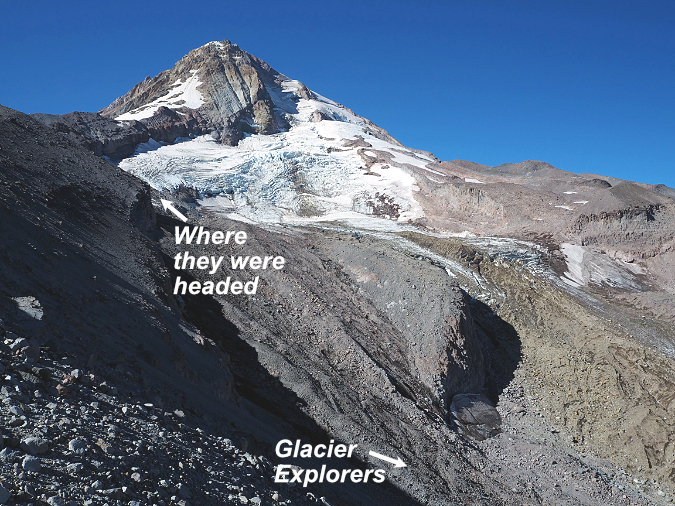

As tough as it has been to witness the accelerating effects of global warming on Mount Hood’s glaciers in past years, the early summer view of the Eliot Glacier remains one of the most impressive sights in WyEast Country. In this view from farther up the Cooper Spur trail (below) a few weeks later, a group of hikers is silhouetted against the mountain, giving scale to the enormity of the glacier as it tumbles down the mountain.

Hikers framed against the Eliot Glacier in Summer

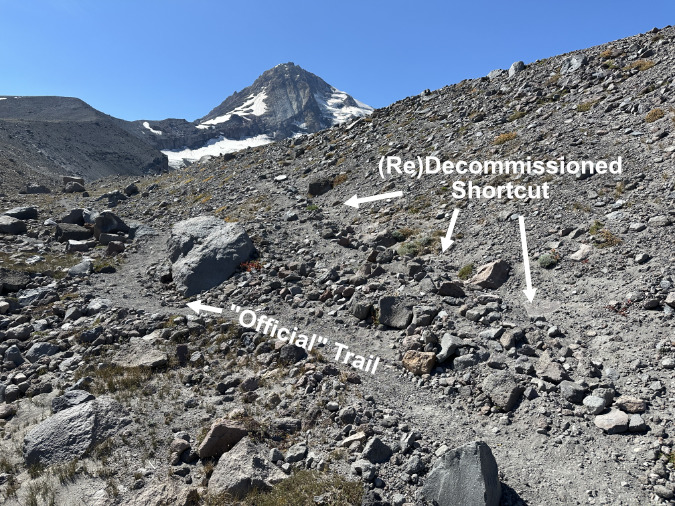

Many of the trails in the Cooper Spur area are as unofficial as they are historic, dating back to the earliest recreation visits to the mountain in the late 1800s and early 1900s, when the Cloud Cap Inn was in its heyday. Today, the continue to be as heavily traveled as the formal trail system. This is made possible by a largely unseen corps of unofficial trail tenders that have helped tend to these routes for decades, as well as the official Timberline and Cooper Spur routes. I know, because I’ve adopted a few of these trails, and I always see the handiwork of others when I’m working there.

Last July, my unofficial trail work focused on retiring a persistent shortcut just below the crest of the South Eliot Moraine. It’s caveman work, as you can see in the schematic below – simply covering the shortcut with rocks large enough to discourage people from taking the shortcut. It’s a never-ending task, as new routes are formed instantly in this open, loose alpine terrain when just one group hikers decides to leave the established trail and make their own way.

Trail tending along the South Eliot moraine

In the era of cell phones and GPS, these shortcuts are becoming more numerous and persistent. Why? Because the errant digital tracks from lost hikers following dead-ends or short cuts are blindly added to the big data commercial websites that cater to hikers. It’s among the many reasons to avoid commercial apps and social media for hiking guidance, especially when we have TKO’s free Oregon Hikers Field Guide for trails in Oregon and Southwest Washington, a non-profit resource written by hikers, for hikers.

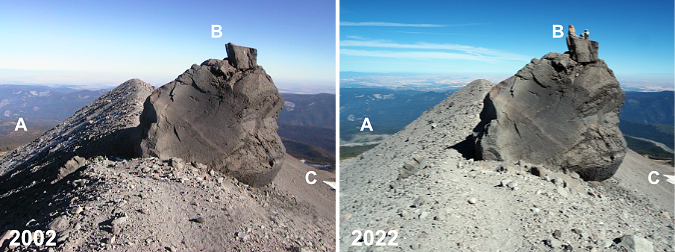

The Cooper Spur Shelter, itself, was also in need of some volunteer tending this year, as the stovepipe in the south corner of the structure has rusted through and that seems to have led to a collapse of the stone wall surrounding it (below).

Recent collapse of the south shoulder of the Cooper Spur shelter

While it’s possible the U.S. Forest Service will repair this, I’m going to guess that it will fall to volunteers that I’ve seen working on the structure in the past. I’ve come across them many times over the years, as early as this view (below) taken 22 years ago, when a group of volunteers was repairing that same south corner of the building. Like most of the trails around Cooper Spur, the shelter also represents an ongoing volunteer effort to ensure it survives.

Volunteers repairing the south wall of the shelter more than 20 years ago

For the August image in the new calendar, I chose the view from Inspiration Point (below), a rocky spot along the Cloud Cap Road that provides a sweeping view of the Eliot Branch canyon and Mount Hood’s steep northeast side. This has been a popular tourist stop since visitors begin arriving at the Cooper Spur Inn by horse and buggy in the 1890s.

The August calendar image features this classic view of Mount Hood from Inspiration Point

Inspiration Point still offers one of the finest views of both the Coe and Eliot glaciers, the two largest on the mountain. The Coe is the lesser known of the two due to its remote location on the rugged north face of the mountain, and this viewpoint is one of the few places with a close-up look accessible by road.

Coe Glacier from Inspiration Point

The steep, unofficial trail to Inspiration Point has been on my list of adopted trails for nearly 20 years, and despite its short length, keeping this little path intact has been a challenge – especially in the years since the 2011 Dollar Lake Fire swept through and left many standing snags that are still periodically falling across the trail.

If you’re not an avid hiker and looking for a short side trip on your way to Cloud Cap, watch for the following signpost at an obvious switchback in the road at about the 3 mile mark (below). From the sign, the trail drops roughly 300 feet to the rocky overlook of Inspiration Point.

Inspiration Point trail marker

What does the “1” stand for in this unofficial trail marker? It dates back to a brochure and map once published by the Forest Service that described the history of the Cloud Cap area by numbered waypoints along the road. This signpost and an old, mounted wagon wheel further up the road are all that remains from that effort to share the local history. I do plan to feature the brochure in a future blog article, along with mileage waypoints to guide visitors, in lieu of the old markers that were once here.

Inspiration Point trail marker… a reminder of an interpretive story that was once told here

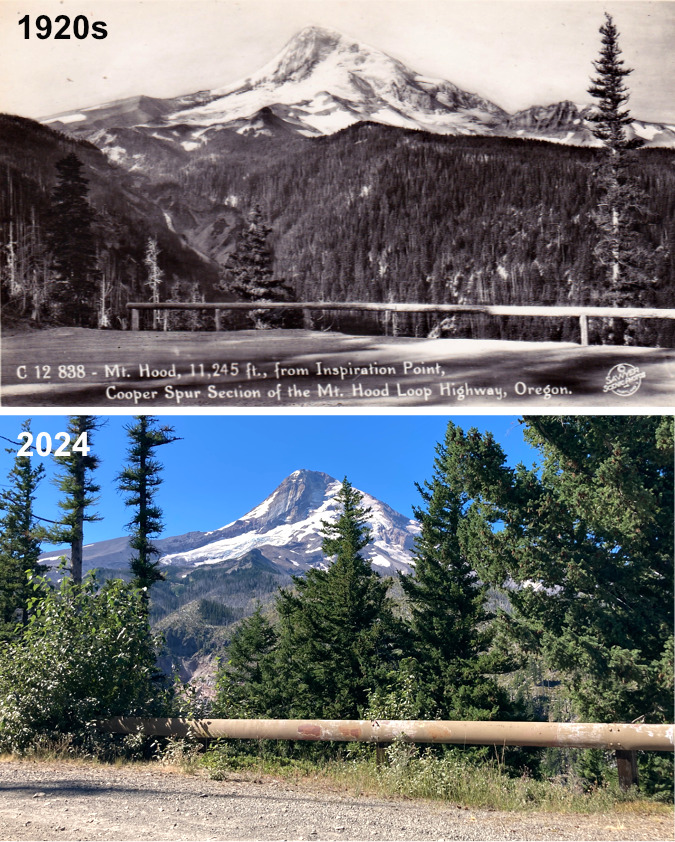

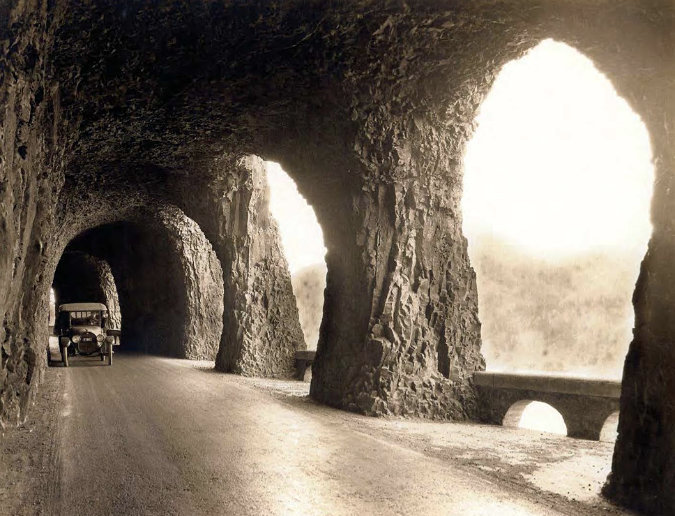

For the best view from Inspiration Point, the short trail is a must, but there was a time when you could take in the view from road as you motored your Model T up to Cloud Cap Inn. In fact, an old guardrail that I think might be the original shown in a 1920s postcard view (below) is still there – albeit with a few trees now partly blocking the view.

The view from Inspiration Point – then and now

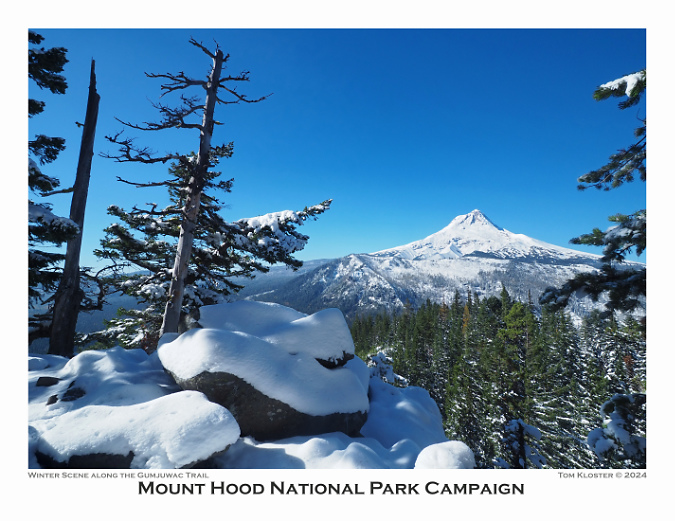

For the September calendar image, I stayed on the mountain and chose an early fall scene at WyEast Basin (below). This photo was taken on a hike in October of this year along the Timberline Trail, from WyEast Basin to Elk Cove, when the huckleberry foliage had turned a brilliant crimson and the alpine meadows to shades of yellow and gold.

WyEast Basin on Mount Hood’s north side is the September image

This photo (below) from the descent into Elk Cove is also from that day, showing the light dusting of early snow that had fallen on the summit the day before.

The Timberline Trail approach to Elk Cove lights up with color in autumn

I considered using this view of the upper meadows at Elk Cove (below) from that October trip for the calendar, before realizing just how many times I’ve featured Elk Cove over the years! Lovely as it is, this year I went for a change of scenery with the WyEast Basin scene.

Elk Cove in autumn with an early dusting of snow on the mountain

One pleasant surprise at Elk Meadows this year was a new trail sign located at the Timberline Trail junction with the Elk Cove Trail. The old sign had pretty much disintegrated in recent years, causing a fair amount of confusion for hikers, based on the number of times I helped people find their way at that junction.

One benefit of coming to Elk Cove every year is the opportunity to track changes there over time. This includes trail signs, and in a place where the winter snowpack regularly reaches 10 feet or more in winter, it’s no wonder that these signs take a beating. As you can see from the photo sequence below, the two small signs pointing to “campsites” get the award for most durable. They were already quite weathered in 2010 when the previous “new” trail sign was installed. By 2023, the “new” main sign from 2010 was falling apart. This year, both the main trail sign and the “no camping in meadows” sign were completely replaced, while the two “campsites” signs are still doing their job.

Elk Cove trail signs over the years

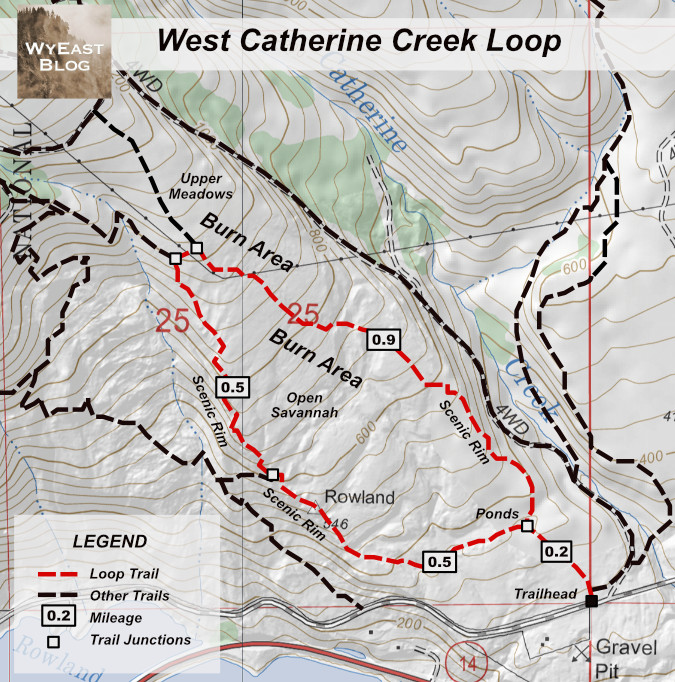

On the hike back from Elk Cove, I stopped to collect some trail condition photos at WyEast Basin, where the growing stream of hikers has begun to take its toll on the meadow. Some of this is the result of hikers simply stepping off the trail when passing one-another on a busy section of the Timberline Trail, but the widening tread is mostly the result of the original trail becoming trenched from heavy use, then becoming a muddy ditch when snowmelt fills it early in the hiking season. Hikers then opt to walk on either side to keep their boots dry, gradually destroying the meadow vegetation in the process.

This schematic (below) shows the original trail at the center (now a trench) as a white dashed line and shoulder paths in red dashed lines, where hikers have already destroyed an alarming amount of meadow vegetation.

Growing damage from trail overuse at WyEast Basin

Over time, this parallel use paths on both sides of the trenched trail will turn into a muddy slog, too, resulting in an ever-widening trail across a beautiful meadow. I’m hoping to find a way for TKO volunteers to restore this trail with a different design that anticipates the muddy season, perhaps even something as bold as a turnpike, or raised section of trail between parallel logs that is designed to keep the trail tread dry by elevating it above the surrounding ground. Below is a recent example from McIver State Park.

Trailkeepers of Oregon (TKO) volunteers building a turnpike on soggy ground at McIver State Park (photo: TKO)

[click here for a larger version]

The second photo in the above example shows a drainage features, one of the potential benefits of a turnpike at WyEast Basin, as the Timberline Trail crosses at least three small streams that meander through the meadow. However, turnpikes are typically built from found materials near the trail (logs, rocks and soil), which could prove to be challenging in an alpine, wilderness environment.

For the October image in the new calendar, I went back to Wahcella Falls. It’s not the first time a waterfall has appeared twice in a single calendar, but it was the combination of fall colors and a person in the photo – a rarity for me – that made the case. Look closely (below) and you’ll see a hiker in front of the falls, taking in the magnificent view.

Wahclella Falls (and a hiker) with fall colors is featured as the October image in the calendar

Earlier in this article, I included a photo of Wahclella Falls from an off-trail viewpoint taken in early spring. By late October each year, the same view lights up with gold and yellow fall colors (below) that are becoming even more prevalent in the aftermath of the 2017 Eagle Creek Fire that swept through this canyon. That’s thanks to the rapid recovery of broadleaf trees like Bigleaf and Vine maple that are taking advantage of the open forest conditions created by the fire, and bouncing back from roots and stumps that survived the burn.

Fall colors at Wahclella Falls have become more dramatic since the 2017 fire

Bigleaf Maple are the real stars in this comeback story, with most growing from the surviving stump of a parent tree killed by the fire. The new access to sunlight and explosive growth also makes for super-sized foliage, with individual leaves measuring nearly a foot across (below) underscoring the common name for these essential trees.

Biglieaf maple leaves are growing to gigantic proportions in the post-fire recovery

When I hike this trail, I see the handiwork of Trailkeepers of Oregon (TKO) crews everywhere, as TKOs volunteers have done much to rescue the trail in the aftermath of the 2017 fire. This includes a streamside section where a huge, post-fire logjam of killed trees accumulated just below Wahclella Falls, and piled so high they spilled onto the trail, itself. TKO and Pacific Crest Trail Association volunteers used a combination of saws and ropes to clear the way back in 2021, and today the logjam is still there to remind us of the power of this stream.

TKO crews clearing the logjam from the Wahclalla Falls trail in 2021

TKO volunteers also worked with the Forest Service to build a rustic set of stairs where the trail had collapsed near the falls, leaving a sketchy scramble through this gap in the rocks for hikers to navigate. The rock steps not only make the trail more accessible to everyday hikers, the add another interesting element and a bit of whimsey for young hikers (below) visiting this family-friendly trail for the first time.

Rustic steps built by TKO volunteers at Wahclella Falls area favorite with young hikers

For the November calendar image, I returned to the east side of the mountain and chose a scene captured along the Lookout Mountain Road in late fall. This is the least-visited, less familiar side of the mountain to Portlanders, with a broad, sweeping profile that looks more like other Cascade volcanoes, and contrasts with the familiar, pyramid-shaped summit the mountain presents to the millions who live west of the mountain.

Yellow and gold Larch framing Mount Hood are featured as the November image in the calendar

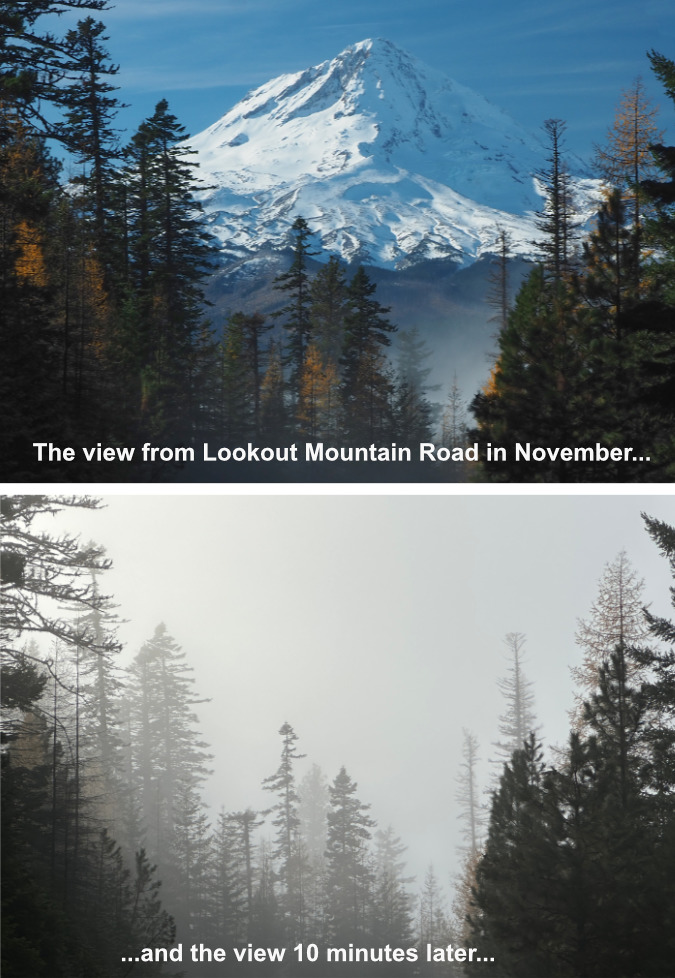

When the conditions are right, the Western Larch here have turned to their yellow and gold autumn colors and the first temperature inversions have arrived, filling the East Fork Hood River valley with fog. The effect can be quite dramatic. On this day the fog layer was growing especially fast, and surged over me in just the view minutes (below) I had to set up my camera!

Fast moving fog at Lookout Mountain!

Having been fogged out on that chilly day, I followed another November ritual in the mountains and collected some greens for holiday decorating. Normally, I look for Noble Fir boughs, but on this day, I gathered some beautiful, blue-tinted Engelmann Spruce greens. You can easily distinguish spruce from other conifers by their sharp needles, making them a bit prickly to work with as holiday greens. Nonetheless, they made for some lovely Christmas arrangements at home!

Engelmann Spruce holiday greens..? Prickly!

Is it legal to collect holiday greens within Mount Hood National Forest? Absolutely, but check their website to see if a permit is required. For 2024, permits are waived, and you may collect up to 25 pounds (that’s a lot of boughs!) in a season. The main restriction is Whitebark Pine, which are now a protected species and may not be collected or cut in any way. These trees only grow at and above timberline, but if you’re unsure of how to identify them, just avoid cutting any pine boughs and stick with fir trees. Leave no trace also applies, so collect boughs as if you were pruning trees in your garden, with cuts made as discreetly as possible.

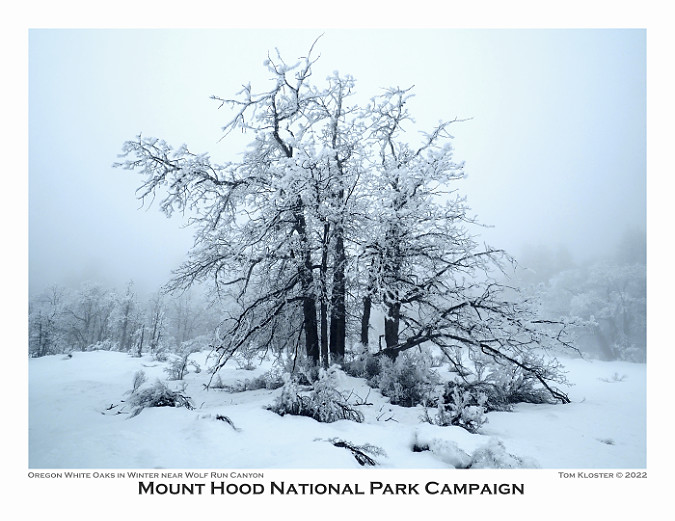

For December, I chose a fairly unconventional image for the new calendar. Continuing with the fog theme, I selected this photo from the Bennett Pass area, where dueling valley fog banks in both the White River and East Fork Hood River valleys were colliding at the pass. The effect in the ancient Noble Fir forests just above Bennett Pass was mesmerizing, with patching of blue sky opening and closing overhead as waves of fog rolled through the big trees.

Ancient Noble Fir forest rising into the fog near Bennett Pass are featured as the December image in the new calendar

Fog bank filling the East Fork Hood River Valley as viewed from above Bennett Pass

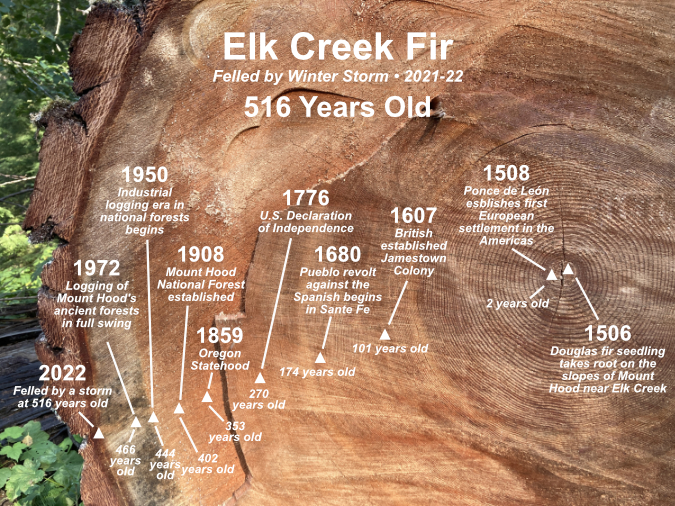

How old are these trees? Some are at least 400 years old. We know this because the area saw heavy logging in the 1970s and 1980s, and many of the giant stumps left from that unfortunate era still remain to tell the story through their tree rings. Fortunately, not all of the big trees were cut, and some truly magnificent old-growth Noble Fir stands remain today.

Noble Fir giants in the fog near Bennett Pass

Noble Fir giants and Mountain Hemlock seedlings in the fog near Bennett Pass

On a more practical note, I was encouraged on that trip to see the Forest Service continuing to gradually improve visitor facilities on the mountain, including a new toilet at the popular winter trailhead at Bennett Pass. While pit toilets might not be a joy for anyone to use, they are essential at busy trailheads, especially for families with young kids. Modern toilets like the new facility at Bennett Pass are also accessible for visitors with mobility devices, removing a very real barrier to our public lands.

New toilets at Bennett Pass – with a view!

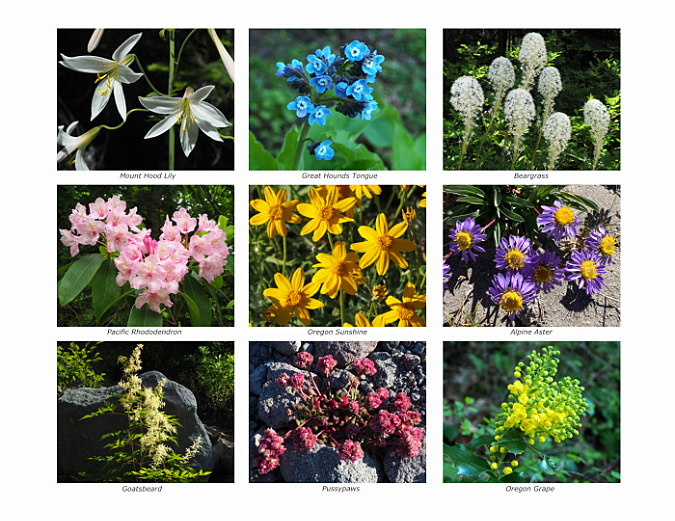

Finally, the back cover of the new campaign calendar features some of the wildflower highlights captured in WyEast Country over the past year (below). Some might be familiar, but I do have one confession to make: the Prickley Pear cactus in the center square wasn’t photographed anywhere near Mount Hood. Instead, it’s over in the John Day country, where I photographed this particular colony near the Painted Hills last spring.

Wildflower mashup on the back of the 2025 calendar

Here’s a closer look at one of the cactus blossoms from that trip (below), showing the unlikely contrast of impossibly delicate flowers emerging from a maze of thorns that make these tough plants so fascinating:

Brittle Prickley Pear near the Painted Hills

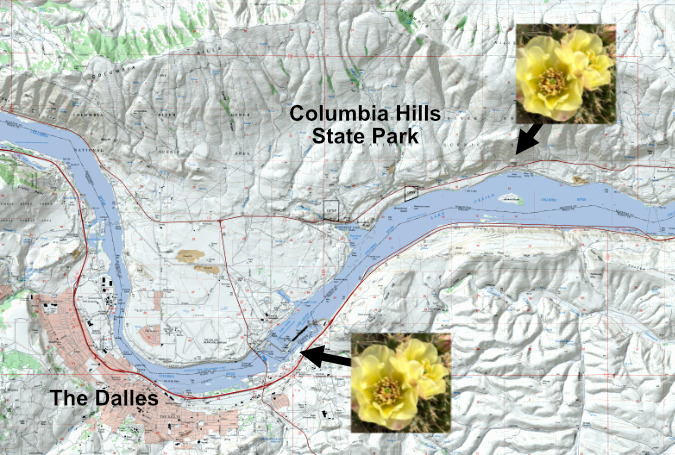

Why include this, then? Because I am admittedly obsessed with our native cacti, and determined to finally photograph them where they grow here in WyEast Country. I have two promising leads on that front that I’ll be following up on this spring. Both are near The Dalles and apparently hidden in plain sight, but I suspect I will have some searching to do!

Where the Prickley Pear grows..?

I’ve spent a lot of time over the years hunting for cactus in Oregon. As spectacular and flamboyant as these flowers are when in bloom, the plants are surprisingly well-camouflaged and hard to find when they’re not… unless you step on one! So, more to come in this story.

…and to spare you from scrolling back to the top, here’s the link if you’d like to order the 2025 campaign calendar featuring these new photos:

2025 Mount Hood National Park Campaign Calendar

… and all proceeds from calendar sales go to Trailkeepers of Oregon (TKO), and they can be delivered anywhere

Looking ahead to 2025

Thanks for reading this far! Mea culpa: I began 2024 with high hopes of a lot of WyEast Blog articles, but my day job and real-life demands got the better of me this year, once again! Therefore, I’m recycling that goal for 2025, and I’ve got some fun topics that I’m eager to dive into.

These include some new digging I’ve done on a massive landslide that completely rerouted one of Mount Hood’s major rivers, plus some new research on what many call “Indian pits” or “vision quest pits” – those mysterious pits found in talus slopes all through the Gorge and in spots around Mount Hood. I’ve also got a history piece on a surprising road race with a WyEast connection, and much more beyond these…time permitting!

The old man and the mountain..

As always, thanks for patiently checking back when my posts become infrequent, putting up with the typos and grammatical errors, and — more importantly — thank you for being a friend of our Mountain and Gorge. I hope to see you on the trail sometime in 2025!

________________

Tom Kloster | December 2024