When the Omnibus Public Land Management Act of 2009 was signed into law by President Obama last year, most of the media attention focused on the new wilderness lands set aside in Oregon. This included a number of new wilderness areas and expansion of existing areas around Mount Hood and in the Columbia Gorge.

But the legislation also contained a new creature of federal law that hardly noticed: creation of the Mount Hood National Recreation Area (NRA). The new designation joined a number of similar “national recreation areas” on United States Forest Service (USFS) land, and added to the confusion that already exists between USFS areas under this designation, and the completely different National Park Service (NPS) designation of “national recreation area.”

The difference is usually found in the fine print, where commercial logging or other extractive uses are allowed in the USFS version of a “national recreation area”, albeit with limitations, whereas such activities are never permitted under NPS management.

This is true for the new Mount Hood NRA, as well. While the 2009 legislation called for the USFS to “provide for the protection, preservation, and enhancement of recreational, ecological, scenic, cultural, watershed, and fish and wildlife values” in the new recreation area, the Forest Service isn’t quite prohibited from carrying out the activities they’ve come to be known for — timber harvest and road building – unless the NRA overlaps a designated wilderness area.

Timber Harvest – The new law allows the “cutting, sale, or removal of timber within the Mount Hood NRA to the extent necessary to improve the health of the forest in a manner that maximizes the retention of large trees, improves the habitats of threatened, endangered, or sensitive species or maintains or restores the composition and structure of the ecosystem by reducing the risk of uncharacteristic wildfire.”

That’s a mouthful, but it does represent a major departure from the status quo commercial timber harvesting that the USFS has employed over the past sixty years across the Mount Hood region. Simply prioritizing the “retention of large trees” is revolutionary for the agency, since these were the prime targets of thousands of timber sales over the past many decades under the pseudo-science of being “decadent” and “unproductive”.

Road Building – The act states that “no new or temporary roads shall be constructed or reconstructed within the Mount Hood NRA except as necessary to protect the health and safety of individuals in cases of an imminent threat of flood, fire, or any other catastrophic event that, without intervention, would cause the loss of life or property; to conduct environmental cleanup required by the United States; to allow for the exercise of reserved or outstanding rights provided for by a statute or treaty; to prevent irreparable resource damage by an existing road; or to rectify a hazardous road condition.”

Another mouthful, and less of a change for the USFS, since pretty much any new road project could be justified under these criteria. But in reality, the agency has experienced collapsing timber revenues and steep cuts in its operating budgets in recent years to pay for new roads. The road building era of the USFS is over, and the Mount Hood National Forest is among several that going through a process to plan for the closure and decommissioning of unneeded roads to reduce maintenance liability and enhance fish habitat. Nonetheless, the new legislation probably makes it a bit harder to build new roads within the NRA, even if the funds are available.

Bicycles – The act doesn’t come out and say it, but the driving purpose behind the creation of the Mount Hood NRA is to provide new protections against logging and development in areas that not only have a high scenic value, but are also popular with mountain bikers. Because bicycles are not allowed inside wilderness areas (yet), the NRA designation became an important political compromise with bike advocates who initially opposed the legislation for the numerous areas that would become off-limits to bikes.

The implication in this intent is that the areas included in the “national recreation area” will be a priority for developing new bike trails and trailhead facilities, including the conversion of surplus logging roads to bicycle trails in some cases. The act provided no funding for this new programmatic emphasis, however, so the work of building and maintaining bicycle trails in the new “national recreation area” will continue to be an uphill struggle, and require the help of volunteers.

Where is the Mount Hood National Recreation Area?

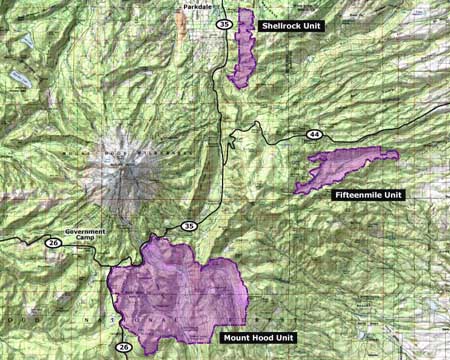

The new Mount Hood NRA covers approximately 34,550 acres in an arc composed of three separate units, each located to the east and south of the mountain. The map below shows the extent and relationship of the three Mount Hood NRA units:

click here for a larger version of the map

The three units of the NRA are located in close proximity to the Mount Hood Loop Highway, and easily accessed from the Portland region, and the communities of Mount Hood and the Gorge. All three are already popular recreation destinations, so the new NRA designation simply embraces and protects this function, while ensuring that cyclists continue to have access.

The Shellrock Unit (map below) of the Mount Hood NRA is the smallest and most northern in the complex. This unit is centered on the popular Surveyor’s Ridge trail complex that features miles of some of the finest single-track cycling in Oregon, and has easy access from Forest Roads 44 and 17.

This is also one of the most heavily logged corners of the Mount Hood National Forest, and will require decades of restoration management to recover. However, the extensive network of logging roads also serves as a prime candidate for conversion to single or dual track bicycle trails. This area features some of the finest views of Mount Hood to be found, so the future is bright for recreation in this unit.

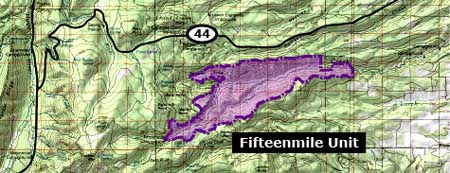

The Fifteenmile Unit (map below) is located due east of Mount Hood, along Forest Road 44, and adjacent to the Badger Creek Wilderness (located to the south). This is also a popular area with cyclists, and like the Shellrock Unit, this area has been brutally logged over the past three decades.

Worse, the remaining forest stands in the Fifteenmile Unit have been hit hard by beetle infestations and drought cycles, resulting in some of the most stressed forests in the Mount Hood region. These conditions, combined with a century or fire suppression where fire is an essential component in the forest ecology has left a tinderbox just waiting for a catastrophic fire.

It will take decades of restoration management to bring back the parkland forests of ponderosa pine, western larch and Oregon white oak that once dominated the area. But as with the Shellrock Unit, the potential for converting logging roads in the Fifteenmile Unit to single and dual track bicycle routes is excellent. The area has a unique blend of high desert and Mount Hood viewpoints that already make it a popular destination, so the NRA designation bodes well for both restoring the forests and expanding recreation here.

The Mount Hood Unit (map below) is the third and final piece of the Mount Hood NRA complex. This is by far the largest of the three units, extending from the Salmon River on the west to the Badger Creek Wilderness on the east, and encompassing a large segment of the upper White River valley. Unlike the other units, the Mount Hood portion of the NRA complex incorporates new wilderness areas, including the Twin Lakes, Barlow Ridge and Bonney Butte wilderness areas. A segment of the Pacific Crest Trail passes through the west edge of this unit of the NRA.

The range of recreation activities is diverse in this largest of the three NRA units, ranging from heavy winter use by skiers, snowshoers and snowmobiles, and summer use by hikers, equestrians and cyclists. The most popular cycling areas are in the eastern portion, along the Gunsight Trail and in the vicinity of Bonney Meadows and the Boulder Lakes.

The eastern portion of this unit is also the most heavily logged, especially in the southeast corner of the NRA, near Boulder Creek. However, like the Shellrock and Fifteenmile units, the logging road network in the Mount Hood unit provide an excellent opportunity for conversion to single or dual track bicycle routes.

What’s Next?

In the near term, the new Mount Hood NRA functions mostly as a curiosity, though in time it will shape USFS decisions on forest management. The main benefit in the short term is more protection for recreation in these areas, and perhaps expanded opportunities for bicycling.

But in the long term, the designation has an intriguing possibility of serving as a steppingstone to National Park status. For example, it could be eventually expanded to cover a much larger (or all) of the Mount Hood National Forest. This could happen in the near term, as demand for recreation from the rapidly growing Portland area continues to outpace what the Forest Service is able to deliver under its current management approach, and is clearly the preferred public use for the forest.

Thus, if a large portion (or all) of the Mount Hood National Forest were to be designated as an NRA, the step to transferring the area to the National Park Service becomes much more plausible, since the Park Service already administers a number of NRAs under its jurisdiction.

In this way, an obscure, almost accidental element of the Omnibus Public Land Management Act of 2009 might have paved a new way for Mount Hood to finally join the ranks of other national parks.

This seems like a really great thing for all outdoor recreation enthusiast and for once cyclist included! Thanks for the wonderful explanation of the new designation.

LikeLike

Thanks for commenting, Robbie! I’m working on followup articles specific to the Surveyor’s Ridge and Eightmile units, an in particular, some ideas for improving the bike opportunities in both areas.

LikeLike

Pingback: Proposal: Waucoma Bicycle Backcountry « WyEast Blog

Pingback: Billy Bob, meet Joe Spandex…! | WyEast Blog

I like the idea of wilderness protection, but Mount Hood will never become a national park. I don’t think its worthy of that status. Mount Hood, although popular and beautiful, is only one out of many Cascade volcanoes that are equally as worthy, if not more so. Mount Baker, Mount Shasta, and Mount Adams comes to mind. Both Shasta and Adams are the two largest volcanoes in the Cascades, and the second and third highest. Mount Baker, barely below Mt. Hood, features rugged mountains and glaciers in and around its slopes.

Mount Hood owes its popularity to its close proximity to Portland. If it switched places with Washington’s Mt. Adams, Mt. Adams would be the popular Portland mountain, and Hood would be the “forgotten mountain.” Mount Rainier obviously deserves its park status, for numerous reasons, like (1) being the tallest in the Cascades, (2) having the largest glacial system in the lower 48, and (3) being surrounded by extremely rugged mountains. I don’t understand why Mt. Hood, about 1/4 the size of Rainier, should receive park status before Mount Baker, Adams, or Shasta does.

Its also frustrating to see so much emphasis on designating new Mt. Hood NF wilderness areas, when places like the Dark Divide in the Gifford Pinchot NF, which is more rugged than anywhere in the Mt. Hood National Forest, still hasn’t received wilderness legislation. The Dark Divide is a land of subalpine meadows, craggy peaks, and dense old growth forests, traversed my miles of trails that see abuse and erosion due to mororized use. Those trails, most of which traverse delicate meadows, were not built to motorized standards, which resulted in serious erosion problems. Even though it may be in Washington, it is still in Portland’s vicinity, yet no one seems to be doing anything about it. Not even Washington conservation groups are doing anything about it. It goes under the radar of so many people.

LikeLike

Never say never, Jason! You’re making the traditional argument against Mount Hood — that we already have Mount Rainier, and don’t need another volcano to represent the Cascades, but I disagree on a couple of points. First, the national parks have moved beyond the era of collecting specimens — consider the number of parks and monuments in the Southwest that protect pretty much the same (or similar) red rock landscapes, for example. Most of those parks were created as an alternative to wilderness designations as a way to keep the areas from being commercially developed, and the same argument applies to the more spectacular parts of the Cascades, including Mount Hood (and I would agree — Mount Baker ought to be added to North Cascades, too).

The other argument specific to Mount Hood is that my proposal covers the Mount Hood Loop Highway, including the Oregon side of the Columbia Gorge. And while the Gorge has more protection than it did before the Scenic Area was created, it still deserves better — along with Mount Hood. The other part of Mount Hood that makes it different than all of the other big volcanoes in the Cascades is the human history in Gorge and on Mount Hood: you’ve got rich Native American history going back millennia in the Gorge (and largely ignored by the Forest Service) while Mount Hood still has remnants from the western migration that could be preserved by the Park Service — the Forest Service is struggling to maintain its own historic facilities, much less care for something like the Oregon Trail.

So, I think it will happen — eventually. There’s a national movement underway to create new national parks for the very purpose of restoring a once-pristine landscape, and Mount Hood is a great candidate for that, too.

Thanks for stopping by, Jason – I appreciate hearing your perspective!

LikeLike

But the human history on Mount Hood is not exclusive to the surrounding regions. Southwest Washington, for example, has a very rich Native American history, as well as an interesting forest service history. Secondly, if we were to make a Mount Hood National Park, it should not include the Columbia River Gorge, which is a completely separate landform. The Oregon side of the Gorge is no less dramatic or scenic than the Washington. Personally, my favorite drive through the Gorge is Washington’s historic Lewis and Clark Highway (WA-14), for its dramatic vistas, many rustic tunnels, and mostly unobstructed views across the river. What I think should be done is go ahead and designate Mt. Hood National Park, but also designate an entirely separate Columbia River Gorge National Park, encompassing both sides of the Gorge, rather than just the Oregon side. For the North Cascades Park Complex, the park boundaries should expand to include the Washington Pass area, parts of the Payasten Wilderness, and Mount Baker. For the Gifford Pinchot National Forest, the Dark Divide, Silver Star Mountain, and the Cispus-Blue Lake Area should receive wilderness status; the High Lakes Area and the south side of Mount Adams should be USFS national recreation areas, so hikers and bikers can both enjoy the areas’ scenic beauty; and lastly designate the Mount Adams National Volcanic Monument ;

(administered by GPNF). Again, it seems as if an attempt to “scoop up” as much land around Mount Hood to give it a better chance of national park status. If Mount Hood is so special, then it wouldn’t need one half of the gorge to boost its chances. Mount Rainier, Lassen Peak, or Crater Lake didn’t need to scoop up that much land. If Mount Rainier did the same, the White Pass area, and the Goat Rocks, Norse Peak, and William O. Douglass Wilderness areas would be included within its boundaries. Mount Rainier didn’t need to include these gems, yet still was worthy. Same for Mount Hood, it too doesn’t need to be so big, and especially doesn’t need to grab half of the (very different) Columbia River Gorge too. All three volcanoes: Mount Hood, Mount St. Helens, and Mount Adams, are all almost equidistant from the gorge, and no mountain is more deserving of the gorge than the other. Please note that while this sounds negative, I do support the Columbia River Gorge’s inclusion in the national park system, and I (partly) support Mount Hood’s inclusion, but I disagree on the boundaries. In summary, I think both geologic features should be separate units.

LikeLike