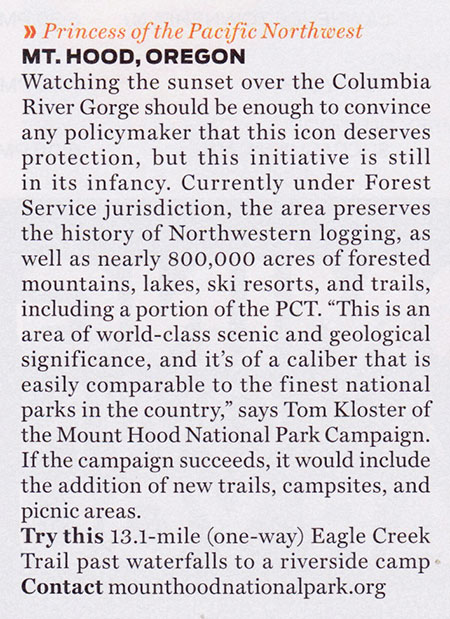

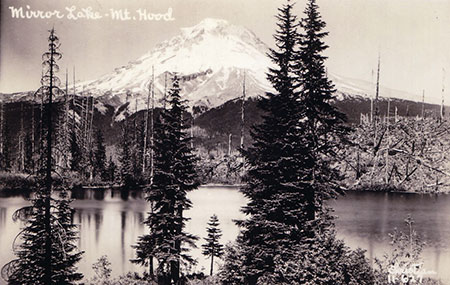

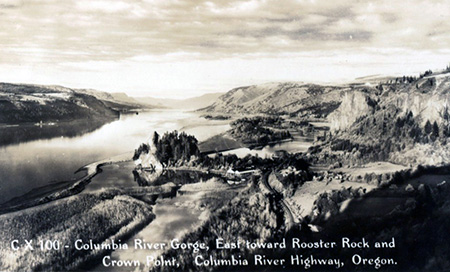

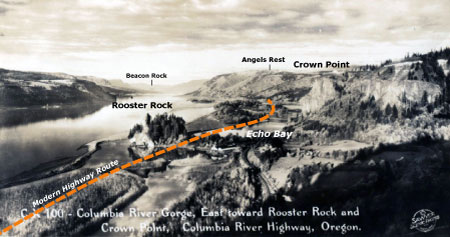

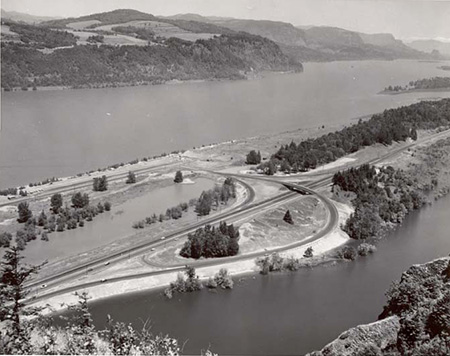

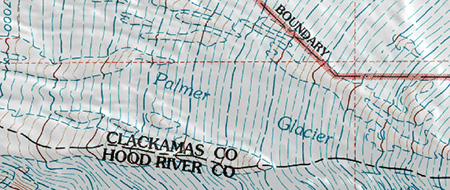

Early 1900s view of Mount Hood and Bull Run Lake, with Hiyu Mountain on the far right and Sentinel Peak on the left

Hidden in plain sight at the foot of Mount Hood and the headwaters of Portland’s Bull Run watershed, Hiyu Mountain is a little-known, much abused gem. No one knows why this graceful, crescent-shaped mountain was named with the Chinook jargon word for “much” or “many”, and sadly, only a very few know of Hiyu Mountain today.

This little mountain deserves better. The broader vision of the Mount Hood National Park Campaign is to heal and restore Mount Hood and the Gorge as a place for conservation and sustainable recreation, ending a century of increasing commercial exploitation and profiteering. As part of this vision, Hiyu Mountain could once again become a place of “hiyu” beauty, where snowcapped WyEast fills the horizon and where Bull Run Lake, indigo source of Portland’s drinking water, could finally be seen and celebrated by the public these lands belong to.

Two Worlds

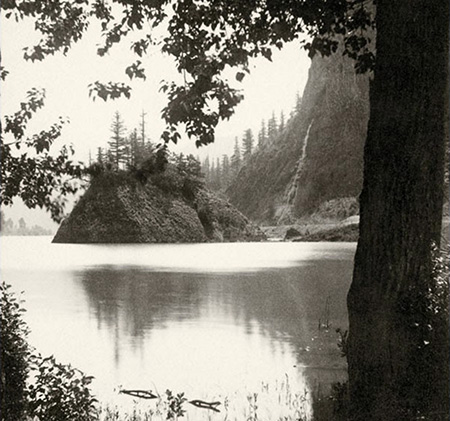

Dodge Island and Mount Hood from Bull Run Lake; Hiyu Mountain is the tall, crescent-shaped ridge rising behind the island (photo courtesy Guy Meacham)

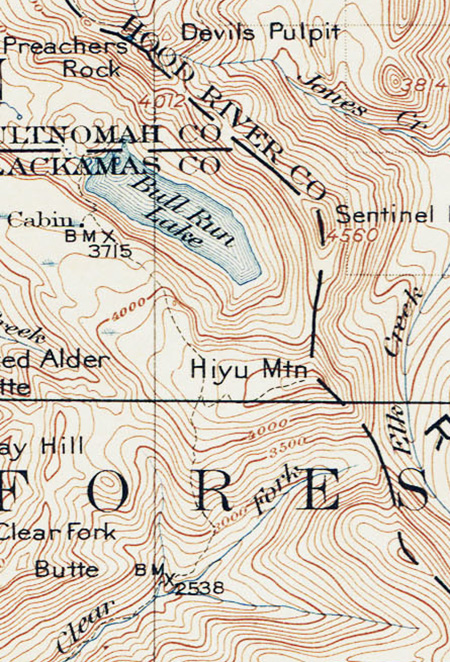

Hiyu Mountain rises 1,500 feet directly above Bull Run Lake, the uppermost source of Portland’s water supply. Lolo Pass is on the south shoulder of the mountain, connecting the Hood River and Sandy River valleys. The two sides of Hiyu Mountain mountain couldn’t be more different.

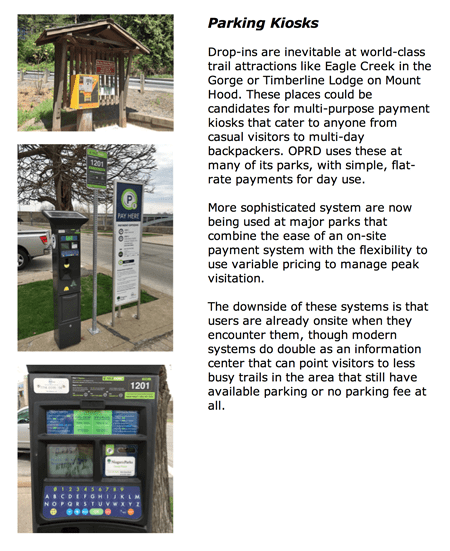

The northern slope that forms the shoreline of the Bull Run Lake is almost untouched by man, almost as pristine as it was when the Bull Run Watershed was established in the late 1800s.

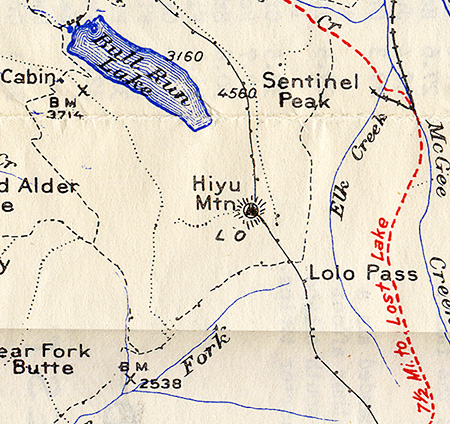

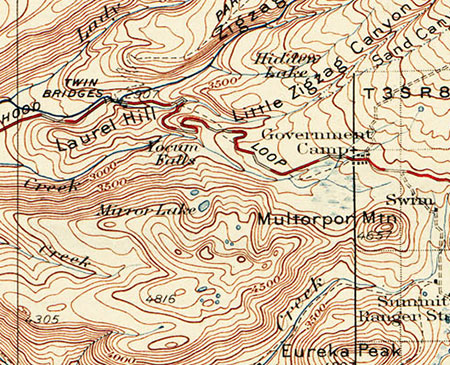

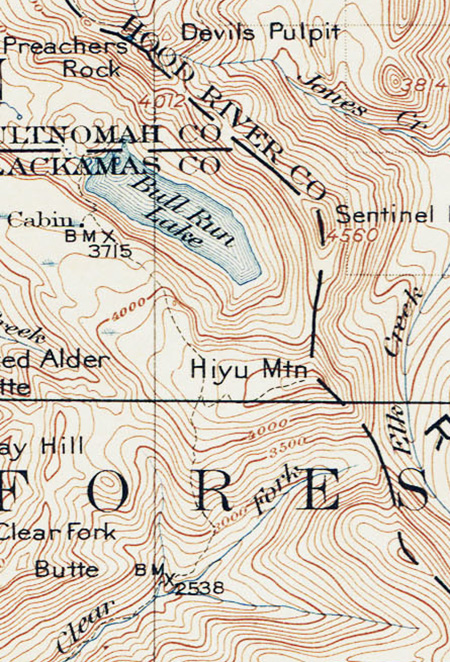

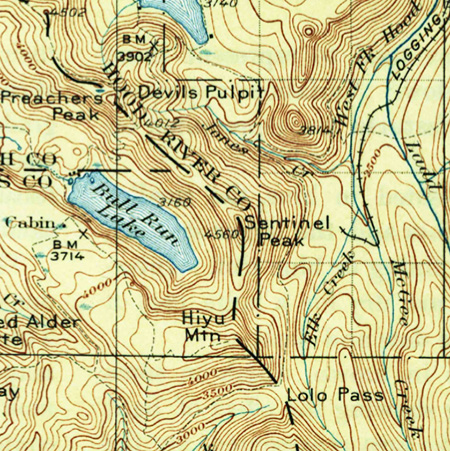

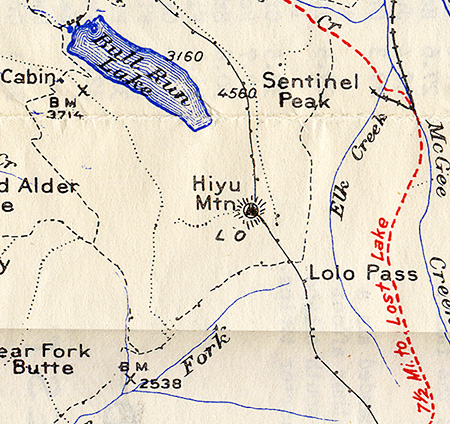

Early 1900s map of Hiyu Mountain and Bull Run Lake

Massive old growth Noble fir forests tower along these northern slopes, where rain and snow from Pacific storm fronts is captured, emerging in the crystal mountain springs that form the headwaters of the Bull Run River.

Almost no one visits this part of Bull Run, save for an occasional Portland Water Bureau worker. This land has been strictly off-limits to the public for nearly 120 years, and remained untouched even as the Bull Run Reserve was developed as a municipal watershed.

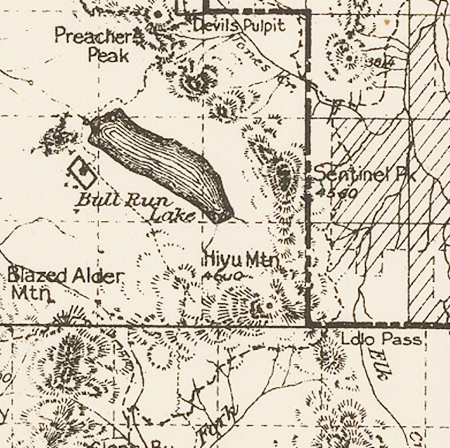

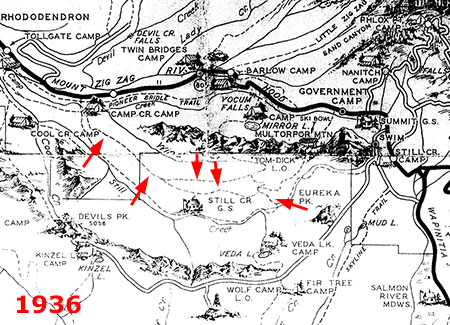

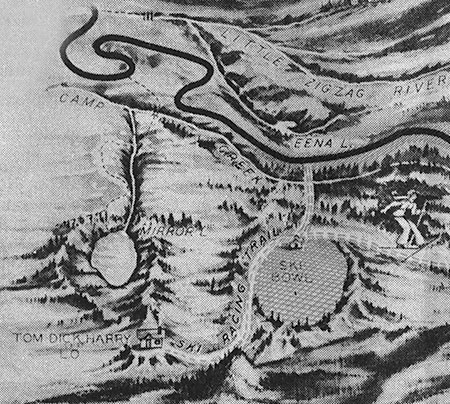

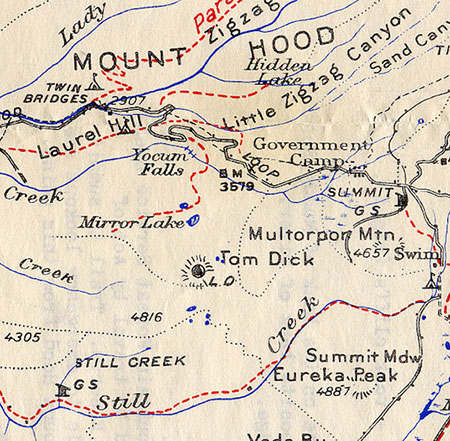

Early 1900s map showing Hiyu Mountain and the first trails over Lolo Pass

On the south slope of Hiyu Mountain things were surprisingly pristine until the 1950s. This area was also part of the original Bull Run Reserve, but was later ceded – in large part because the south slopes of Hiyu Mountain drain to the Clear Fork of the Sandy River, and away from the Bull Run watershed.

Since the 1950s, a conspiracy of forces has almost completely altered the south face of the mountain and its summit crest. By the mid-1950s, the Forest Service had begun what would become an extensive industrial logging zone here, mining ancient trees in dozens of sprawling, high-elevation clear cuts in the remote Clear Fork valley.

These forests will take centuries to recover, and are today mostly thickets of plantation conifers in woeful need of thinning. The maze of logging roads constructed to cut the forests are now buckling and sliding into disrepair on the steep mountain slopes.

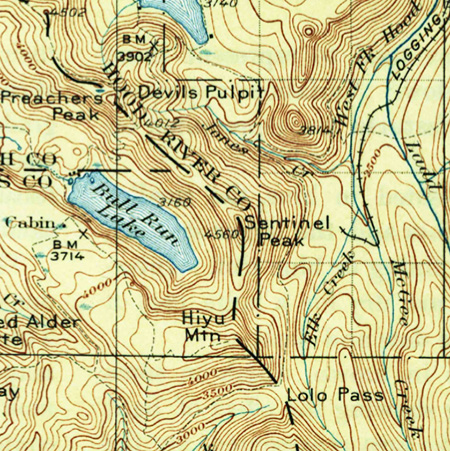

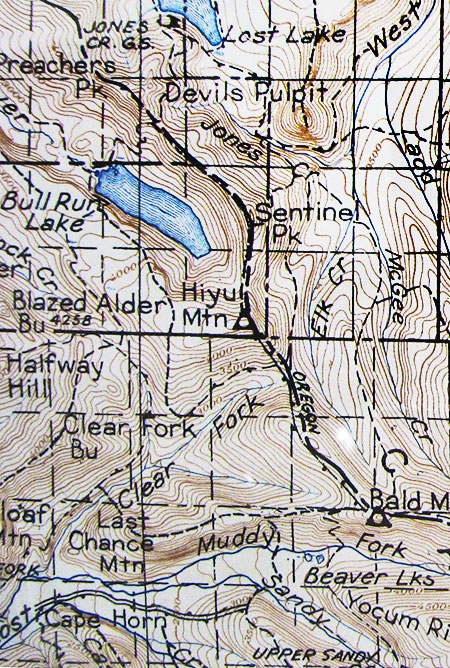

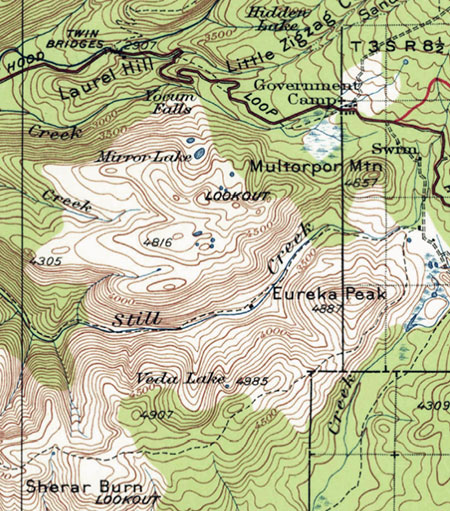

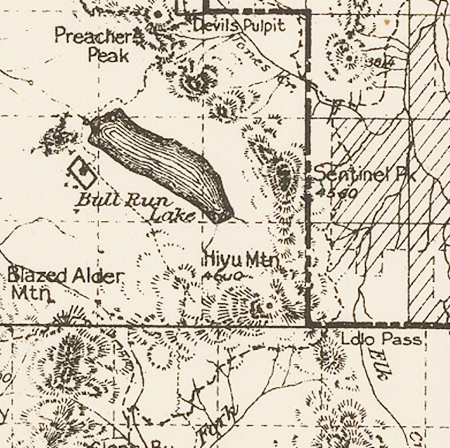

1927 map of Hiyu Mountain, Bull Run Lake and the south corner of Lost Lake

By the late 1950s, a logging road had finally pushed over the crest of Lolo Pass. At just 3,330 feet, Lolo is the lowest of mountain passes on Mount Hood and a route long used by Native Americans. But surprisingly, it was the last to see a road in modern times. The road over Lolo Pass coincided with the completion of The Dalles Dam in 1957, some 50 miles east on the Columbia River.

While the dam is most notorious for drowning Cello Falls, a place where native peoples had lived, fished and traded for millennia, it also sent half-mile wide power transmission corridors west to Portland and south to California. Thus, the new road over Lolo Pass enabled the most egregious insult to Hiyu Mountain, with the parade of transmission towers we see today tragically routed over the shoulder of Mount Hood.

The power corridor took advantage of the easy passage over Lolo Pass, an absence of tourists and public awareness (at the time) on this remote side of the mountain, and was built with complete disregard for the natural landscape. It remains as Mount Hood’s worst scar.

The Bonneville Power Administration’s quarter-mile wide perpetual clearcut that follows their transmission lines over the shoulder of Hiyu Mountain

Today, the south side of Hiyu Mountain remains a jarring landscape of ragged clearcuts, failing logging roads and the quarter-mile wide swath of power lines.

With regular clearing and herbicides, the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA) ensures that nothing much grows under its transmission lines except invasive weeds. It’s a perpetual, linear clearcut that serves primarily as a place for illegal dumping and a shooting range for lawless gun owners who ignore (or shoot) the hundreds of BPA “no trespassing” signs. It is truly an ugly and shameful scene that cries out for a better management vision.

The Lookout Era

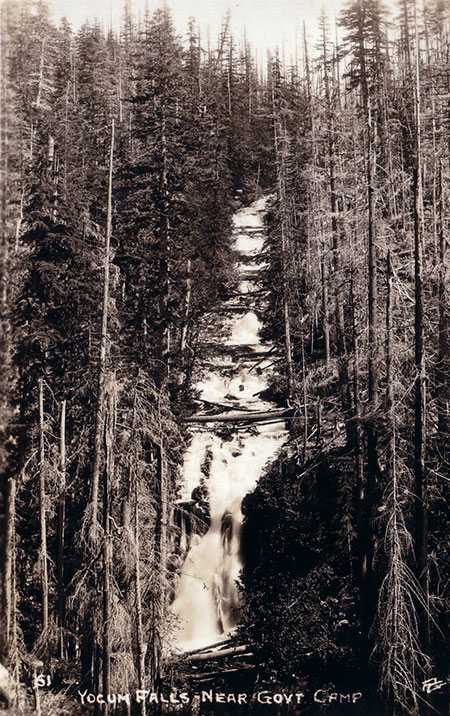

The original lookout tower on Mount Hood in the late 1920s

By 1929, the Forest Service had built a 20-foot wooden lookout tower with an open platform atop Hiyu Mountain (above). It was an ideal location, with sweeping views of both the Bull Run Reserve and the entire northwest slope of Mount Hood. A roof was soon added to the original structure, but in 1933 a more standard L-4 style lookout cabin replaced the original structure (below). The new lookout provided enclosed living quarters for lookout staff, complete with a cot, table and wood stove – and an Osborne fire finder in the center of the one-room lookout.

The 1933 Hiyu Mountain Lookout in the 1950s

Osborne Fire finder in the 1930s (USDA)

When the new Hiyu Mountain lookout was constructed in 1933, the Forest Service was also completing a comprehensive photographic survey from its hundreds of lookout sites throughout Oregon. These photos are now an invaluable historical record. Forest Service photographers used a special panoramic camera to capture the full sweep of the view from each lookout, creating a trio of connecting panoramas from each location.

The following photographs are taken from a panoramic survey at Hiyu Mountain in 1934, and tell us what the area looked like in those early days.

The first photo (below) looks north, toward Bull Run Lake, but also shows the fresh fire lane cut into the forest along the Bull Run Reserve boundary – visible on the right and along the ridge at the top of the photo.

Bull Run Lake from Hiyu Mountain in 1934

(click here for a larger photo)

The fire lane is no longer maintained and has now largely reforested. The northern view also shows a simple wind gauge mounted on a pole below the lookout tower and the perfect cone of Mt. St. Helens on the horizon, as it existed before its catastrophic 1980 eruption.

The view to the northeast (below) shows Mount Adams on the distant horizon, and a completely logged West Fork Hood River valley, below. The Mount Hood Lumber Company milled the old growth trees cut from this valley at the mill town of Dee, on the Hood River. The ruins of their company town (and a few surviving structures) can still be seen along the Lost Lake Highway today. Trees cut in the West Fork valley were transported to Dee by a train, and a portion of today’s Lolo Pass road actually follows the old logging railroad bed.

The logged-over West Fork valley from Hiyu Mountain in 1934

(click here for a larger photo)

Unfortunately, much of the West Fork valley continues to be in private ownership today. Longview Fiber owned the valley for decades, but sold their holdings in a corporate takeover in the late 2000s to a Toronto-based Canadian trust. More recently, Weyerhauser took ownership of the valley, and has embarked on a particularly ruthless (and completely unsustainable) logging campaign that rivals the complete destruction seen in these photos from the 1930s (watch for a future WyEast Blog article on this unfortunate topic).

To the southeast (below), Mount Hood fills the horizon in spectacular fashion, but there are some interesting details in the photo, too. In the foreground, the rocky spur that forms the true summit of Hiyu Mountain has been cleared to enhance the lookout views. The continued swath of logging in the West Fork valley can be seen reaching the foot of Mount Hood on the left.

Mount Hood from Hiyu Mountain in 1934

(click here for a larger photo)

A detailed look (below) at the western panorama in the Hiyu Mountain series shows a lot of cleared forest, a necessity as the summit ridge continues in this direction for than a mile, blocking visibility for the new lookout. In this detailed scene, we can also see stacked logs and lumber that were presumably used to build a garage and other outbuilding that were added to the site in the 1930s.

Recently cleared trees at the Hiyu Lookout site in 1934

(click here for a larger photo)

When it was constructed, the lookout on Hiyu Mountain was remote and reached only by trail. Materials for the new structured were brought in by packhorse. The nearest forest guard station was at Bull Run Lake, where Portland Water Bureau rangers staffed log cabins while guarding the water supply.

A dense network of trails connected the Hiyu Mountain lookout to Bull Run Lake and other lookouts in the area. As the 1930s era Forest Service map (below) shows, a telephone line (the dash-dot line) also connected Hiyu Mountain to other lookouts on Hiyu Mountain and to the cabins at Bull Run Lake. The phone line north of the lookout followed the fire lane, and is likely still there, lost in the forest regrowth.

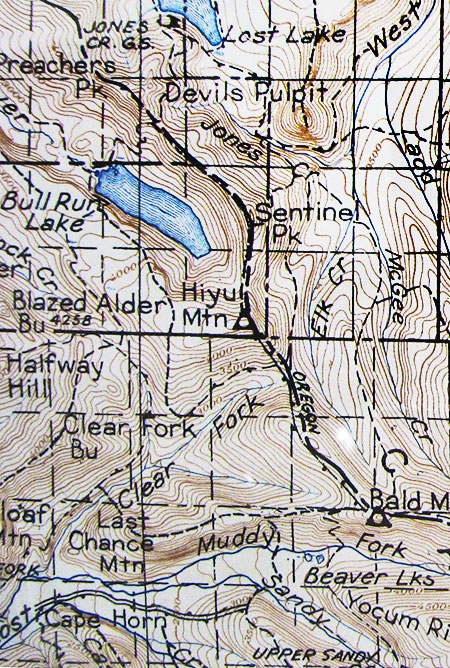

1930s map of Hiyu Mountain showing the extensive trail network of the pre-logging area

The 1930s forest map also shows the original alignment of the (then) new Oregon Skyline Trail, now the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT). According to the map, the trail crossed right through the logged-over area of the West Fork valley (between the tributaries of Elk Creek and McGee Creek on the map) in the 1934 panorama photos, so not exactly a scenic alignment. Today’s McGee Creek trail is a remnant of this earlier route from Mount Hood to Lost Lake.

Today’s PCT stays near the ridge tops, roughly following some of the old forest trails from Mount Hood to Lolo Pass, then across the east slope of Hiyu Mountain, toward Sentinel Peak. A 1946 forest map (below) shows the Oregon Skyline Trail to already have been moved to the ridges between Bald Mountain and Lost Lake, though the area was still without roads at the time.

1946 forest map of the Hiyu Mountain area – oddly, Lolo Pass is not even marked!

By the early 1950s, there were dozens of forest lookouts in the area north of Mount Hood, with structures on nearby Buck Mountain, Indian Mountain, Lost Lake Butte, Bald Mountain, East Zigzag Mountain, West Zigzag Mountain and Hickman Butte. All were within sight of the lookout on Hiyu Mountain, and must have provided welcome — if distant – company to lookout staff.

During the 1950s, roads were finally pushed into the Clear Fork valley and over Lolo Pass as the industrial logging era began on our national forests. During this period, a logging road was constructed between Lolo Pass and Bull Run Lake, including a spur that climbs to the summit of Hiyu Mountain.

Bull Run Lake from Hiyu Mountain in the 1950s

Though not widely known today, the logging agenda of the U.S. Forest Service from the 1950s through the 1980s did not spare the Bull Run Reserve. In the 1960s and 70s, alone, some 170 mile of logging roads were cut into the mountain slopes of Bull Run. By the 1990s, 14,500 acres of these “protected” old growth forests of 500-year old trees had been cut, or roughly 20 percent of the entire watershed had been logged. Public protests and legal challenges to stop the logging began as early as 1973, but only in 1996 did legislation finally ban the destruction of Bull Run’s remaining ancient forests.

By the early 1960s, the Forest Service had begun to phase out the forest lookouts, and Hiyu Mountain’s lookout structure was removed by 1967. Since then, the main function of the summit road has been to log the south slope and summit ridge of the mountain and to provide access to radio antennas where the old lookout building once stood. The easy road access to the summit also brought one of Mount Hood’s seismic monitors to Hiyu Mountain in more recent years.

The Ridiculous Red Zone

Hiyu Mountain is the long, dark ridge rising above Bull Run Lake and in front of Mount Hood in this 1960s photo

As recently at the 1980s, it was still legal – and physically possible – to follow the old, unmaintained lookout trail from Lolo Pass to the summit of Hiyu Mountain. Sadly, the Forest Service has since officially closed the trail as part of their stepped-up campaign with the City of Portland Water Bureau to deny any public access to the Bull Run Reserve, even for areas outside the physical watershed.

A few have dared to follow the Hiyu Mountain trail in recent years, and report it to be overgrown, but in excellent shape. The trail climbs through magnificent old Noble fir stands before emerging at the former lookout site. The route doesn’t come remotely close to the actual water supply in Bull Run, which underscores the ridiculousness of the no-entry policy.

Meanwhile, in recent years the City of Portland has been forced to flush entire reservoirs at Mount Tabor and in Washington Park because of suspected contamination from vandals. Yet, these reservoirs continue to be completely accessible and uncovered and in the middle of the city, protected only by fences.

Mount Hood from Bull Run Lake – Hiyu Mountain is the tall ridge immediately in front of Mount Hood in this view (Portland Water Bureau)

Why so little security in the middle of Portland, where the actual water supply is in plain sight and easily vandalized, and so much security where there is little chance of coming anywhere near the water source?

The answer seems to be a mix of dated laws, entrenched bureaucracy and a heavy dose of smokescreen marketing. Portland’s water supply has been under scrutiny by federal regulators in recent years for its vulnerability to tampering – or, perhaps more likely, natural hazards like landslides (Bull Run Lake was created by one, after all), catastrophic forest fires or even a volcanic eruption at nearby Mount Hood. This is because the water coming into city pipes is currently unfiltered.

Portland’s Water Bureau provides day tours for a limited number of Portlanders each summer willing to pay $21 for the trip. This is the only way the public can legally visit Bull Run (Wikimedia)

Portland’s elected officials are loathe to fund the price tag for modernizing the system to make it more safe and resilient. In their effort to avoid having to fund and build a filtration system, the City has instead relied heavily on the feel-good mystique of the Bull Run Reserve as a pristine, off-limits place where such measures simply aren’t needed. So far, Portlanders seem content to buy this excuse for preserving the status quo.

That’s too bad, because it’s always shortsighted to exclude the public from access to our public lands, especially if the purpose is as important as ensuring safe drinking water in perpetuity.

A better approach for both the City and the Forest Service would be just the opposite: look for opportunities to involve Portlanders in their Bull Run watershed, including trails like the route to Hiyu Mountain that could give a rare look at the source of our drinking water. Which brings us to…

A New Vision for Hiyu Mountain?

The popular reproduction lookout tower at the Tillamook Forest Center (Portland Tribune)

We already have a model for honoring Hiyu Mountain’s history at the Tillamook Forest Center, in Oregon’s Coast Range. This relatively new interpretive site is occasionally mocked for its prominent forest lookout tower without a view, but the purpose of the lookout is to educate visitors, not spot fires. Each year, thousands of visitors get a glimpse of how these lookouts came to be, and why they have largely disappeared from the landscape.

A similar project could work at Hiyu Mountain, though a restored lookout tower there could be for the dual purpose of educating visitors on both the history of forest lookouts and the story of the Bull Run Reserve, with birds-eye view of Bull Run Lake from the tower. A restored Hiyu Mountain tower could also provide a more aesthetic alternative for mounting Forest Service communications equipment now installed on top of the mountain.

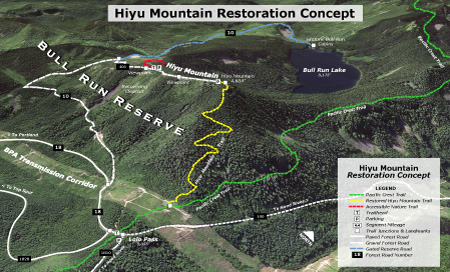

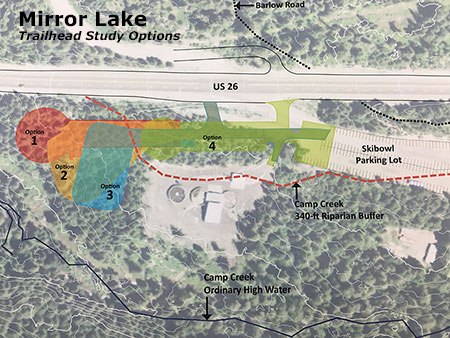

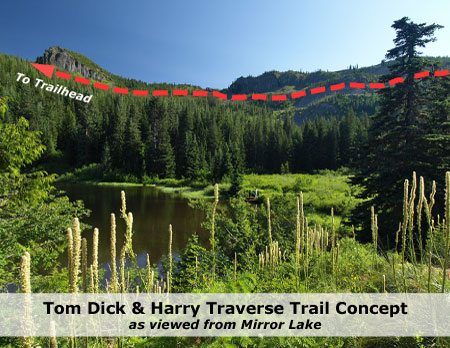

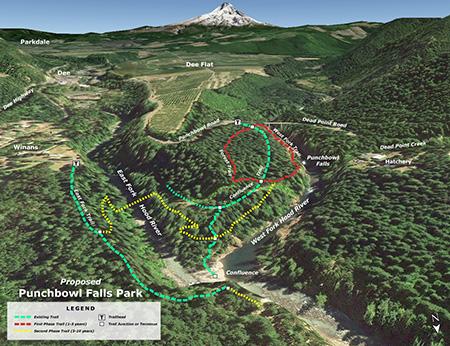

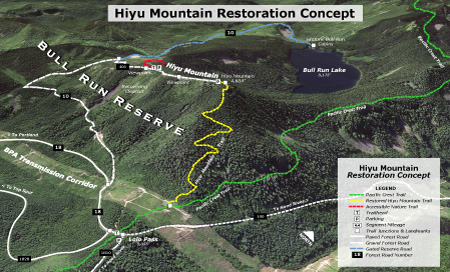

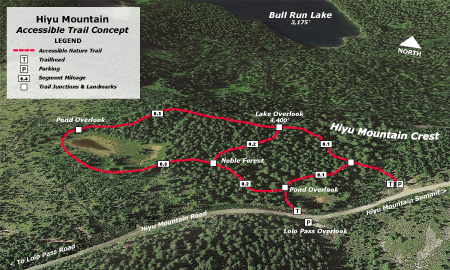

The concept below would reopen the road to the summit of Hiyu Mountain to the public, with a restored lookout tower as the main attraction. Visitors would have stunning views of Mount Hood and into Bull Run Lake. The old lookout trail from Lolo Pass would also be reopened, providing a way for more active visitors to explore the area and visit the restored lookout tower.

(Click here for a larger map)

This concept would not put anyone in contact with Bull Run Lake or any of Portland’s Bull Run water, though it would provide a terrific view of the source of our drinking water. It would also pull back the shroud of secrecy around our watershed that allowed hundreds of acres of irreplaceable Bull Run old growth to forest be quietly logged just a few decades ago – the very sort of activity the public should know about when it’s happening on our public lands.

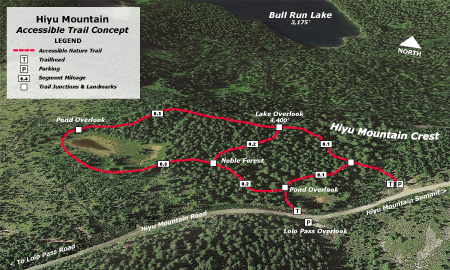

Another feature in this concept is an accessible trail (see map, below) to viewpoints of Bull Run Lake and a pair of scenic ponds that somehow survived the massive Forest Service clearcutting campaign on Hiyu Mountain’s crest.

The idea is to provide much-needed trail experiences for people with limited mobility or who use mobility devices, such as canes, walkers or wheelchairs. Trails with this focus are in short supply and demand for accessible trails is growing rapidly as our region grows. Why build it here? Because everyone should be able to see and learn about their water source, regardless of their mobility.

(Click here for a larger map)

These recreational and interpretive features would also allow Hiyu Mountain to begin recovering from a half-century of abuse and shift toward a recreation and interpretive focus in the future. While logged areas are gradually recovering, the area will need attention for decades to ensure that mature stands of Noble fir once again tower along Hiyu Mountain’s slopes.

What would it take..?

What would it take to achieve this vision? The Hiyu Mountain lookout trail is in fairly good shape, and could be restored by volunteers in a single season if the entry ban were lifted. The concept for an accessible loop could be funded with grants that specifically target accessible trails if the Forest Service were to pursue it. And forest lookout organizations already maintain several historic lookouts in Oregon, so they could be a resource for recreating and maintaining a lookout at Hiyu Mountain.

Welcome to your Bull Run watershed… (Wikimedia)

Most of the infrastructure is already in place, and just waiting for a better management vision for Hiyu Mountain. I’ve described one here, and there are surely others that could provide both public access and restoration.

But only the U.S. Forest Service and City of Portland Water Bureau can move us away from the antiquated entry ban at Bull Run. Hiyu Mountain would be the perfect place to start!