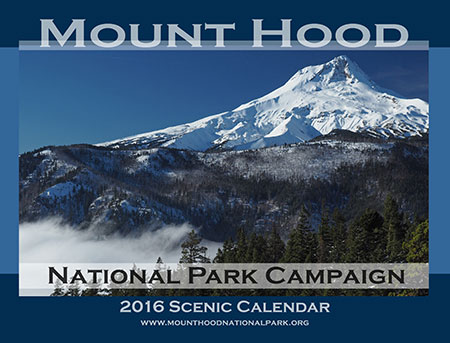

Each year since 2004, I’ve produced an annual “Mount Hood National Park Campaign Scenic Calendar”. It’s mostly for fun and to showcase the mountain (and Gorge) in a way that helps move beyond the too-often heard “it’s too [fill in the defeatist excuse] to become a national park.”

Wrong! In fact, the spectacular scenery, dramatic human history and sheer diversity of ecosystems in such a compact space make it a perfect candidate! Thus, the “idea campaign”, now entering its 12th year.

Each scenic calendar does put a modest $4 into keeping the campaign website and this blog up and running, but the main reason for picking one up is to simply enjoy looking at our someday national park through every month of the year. They sell for $29.95 over on my new campaign store:

Mount Hood National Park Campaign Store

If you’ve purchased a campaign calendar before, you’ll note that I’ve moved from CafePress to Zazzle for printing. This is in part due to CafePress dropping large format calendars from their offerings. But in truth, I’ve had mixed experiences with the company in recent years, and have heard the same from others who purchased calendars there. So, it was time to bail.

By contrast, Zazzle seems to provide a much better customer experience and the print quality is exceptional – especially compared to CafePress. I’ve been impressed, and I think you’ll be pleased, too!

Now, bear with me as I indulge in my annual reflections from the past year as illustrated by photos from the 2016 calendar…

The Cover Shot

Mount Hood and valley fog from Gumjuwac Overlook

The view on the cover of the 2016 calendar is from a favorite viewpoint that is surprisingly unknown and never crowded. It’s along the Gumjuwac Trail, and the combination of a steady climb and not much information on maps or guidebooks to indicate a viewpoint seems to have kept this spot out of the mainstream… for now!

The cover shot came on one of those bright blue mountain days when the East Fork Hood River valley was blanketed in dense, freezing fog, thanks to a classic temperature inversion.

Silver thaw on vine maple along the Gumjuwac Trail

The temperature at the trailhead along the East Fork that November day was a foggy 28 degrees. The first part of the climb along the Gumjuwac Trail was through a wonderland of glazed trees before breaking out of the fog about 1,500 feet above the trailhead. There, the temperature was suddenly in the 40s and allowed for a relatively balmy lunch in the sun!

The Monthly Images

For the January image in the 2016 calendar, I chose a photo taken along the historic Bennett Pass Road (below) after the first big snowfall of the 2014-15 winter season. As it turned out, it was also the last big snowfall! We soon entered a long year of drought in the Pacific Northwest that left the Cascades with the lightest snow pack in years.

January features Mount Hood from Bennett Pass Road

The February image of the north face of Mount Hood (below) was taken from a mostly bare Old Vista Ridge Trail in mid-May, with a fresh coast of spring snow at the upper elevations of the mountain that belied the ongoing drought. The trail would normally have 5-10 feet of snow on the ground at that time of year, but the drought of 2015 was already well underway, and many mountain trails were eerily snow-free by early June.

February features a close-up of the north face of Mount Hood

For March, I chose a close-up photo of Wahclella Falls (below) on Tanner Creek taken in early May. This has become one of the most popular trails in the Gorge, and remains my favorite, as well. In 2015, I hiked this lovely trail a total of seven times, spanning the four seasons.

On this particular trip, an impromptu, full-blown Bohemian wedding unfolded on the rocks above the falls while I was shooting this image – complete with baskets of rose petals and various acoustic instruments wafting (somewhat in tune) above the roar the falls. It was undoubtedly an unforgettable wedding for the lucky couple, and just another quirky Gorge experience for hikers passing through..!

March features Wahclella Falls on Tanner Creek

The Wahclella Falls photo required a bit more commitment than simply showing up with a tripod. The falls are well-guarded with huge, truck-sized boulders, so to capture this image I packed creek waders and eased out to about mid-thigh in very “refreshing” water to get a clear view of the falls. After 20 minutes in the stream, it took awhile for the circulation to return to my legs…

Thawing my legs after some quality time in the middle of Tanner Creek

This year I started a new guided hike series for the Friends of the Gorge focuses on waterfall photography for beginners. Tanner Creek is the perfect trail for this, with world-class scenery along a short, safe loop trail.

Though the main goal for most hikers at Tanner Creek is Wahclella Falls, the lower creek is especially good for learning the camera basics of long exposures and filters. The April scene (below) was captured during one of these guided hikes.

April features a sylvan scene along lower Tanner Creek

While poking around the boulders along Tanner Creek for a good photo that day, I nearly stepped on a pair of garter snakes (below) sunning themselves in the filtered sunlight. I assume this to be a mother and offspring, but will defer to the herpetologists on that point!

Garter snakes on the banks of Tanner Creek

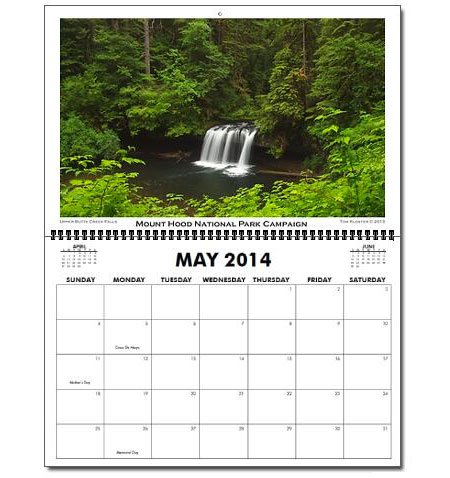

For the May image, I selected a perennial favorite of a lot of photographers, Triple Falls on Oneonta Creek (below). This is one of those spots that just calls out “national park!” It’s a completely unique waterfall that perfectly captures the elements that make Gorge scenes like this unmistakable: bright, crystal clear streams tumbling over sculpted black basalt, framed by velvet blankets of moss and ferns and shaded by the lush foliage of the Cascade rainforest. It’s no wonder the Gorge waterfalls have become iconic, drawing admirers from around the world.

May features Triple Falls on Oneonta Creek

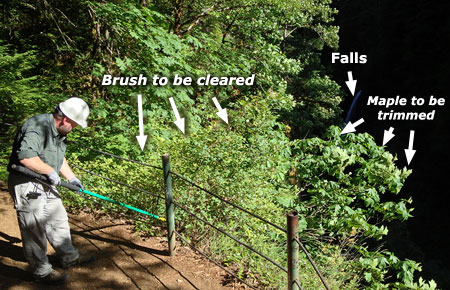

The trail to Triple Falls was briefly closed on a couple of occasions in 2015 thanks to a large landslide that occurred just below Middle Oneonta Falls, about a half mile below Triple Falls. On the way down from my trip to Triple Falls, I ran into Bruce Dungey (below), a U.S. Forest Service trail crew legend who has worked for the agency for 38 years and in the Gorge since 1992. He had been fine-tuning a temporary route his crew had built through the landslide.

Forest Service trail crew legend Bruce Dungey working on the big slide that briefly closed the Oneonta Trail last year

We chatted as he was packing up his gear and hiked back to the trailhead together. Bruce quietly lamented the collapse of funding for trail crews in the Gorge over the time he has worked here. As recently as the 1990s, three crew leaders (including him) each led a crew of five working on Gorge trails. Today, there are a total of three trail workers remaining for the entire scenic area.

During the same period, Bruce has seen trail use explode, and he and his remaining crew are struggling just to keep up with the sheer numbers of hikers. Making things worse are bizarre new “sports” like trail bombing, where hikers intentionally cut across switchbacks for the fun of it, in a race to get to the bottom.

Bruce will soon be retiring, taking an immense amount of knowledge of the Gorge trails with him. My conversation with him was yet another reminder that we all need to work together to rearrange our priorities, and move recreation funding to the top of the priority list at our federal agencies.

June features Owl Point on the Old Vista Ridge Trail

The June image is another from Owl Point (above), a beautiful rocky perch along the Old Vista Ridge Trail. The trail here was almost lost to neglect after being dropped from Forest Service maintenance in the 1970s, but since 2007, this old gem has been gradually restored by a small army of anonymous volunteers.

Today, the old trail looks better than ever, keeping alive one of the earliest routes built on the mountain. Hikers have noticed: the summit register at Owl Point recorded more than 60 entries in 2015, including visitors from as far away as Japan and Europe, and Owl Point is now featured in several hiking guides.

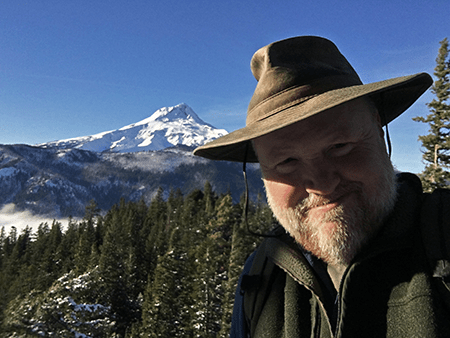

The Owl Point hike took special meaning for me this year, as I was able to take an old friend and college roommate (below) there for a one-day reunion. We couldn’t have had a more idyllic day. It’s no secret that trails are the perfect place for reconnecting with old friends!

Old friends and mountain trails are a perfect combination!

For July, I selected one of my few wildflower scenes from 2015 (below), captured along the Timberline Trail near Timberline Lodge.

July features the Timberline Trail near Timberline Lodge

The early wildflower bloom caught many hikers by surprise, with places like Elk Cove and Paradise Park peaking a full month early from their typical August bloom time. I was among them, and completely missed the bloom at Elk Cove for the first time in over a decade.

The following side-by-side shows Elk Cove still blooming in late August in 2012 and completely gone to seed by August 4 in 2015:

The August image in the new calendar is also from the Timberline Trail, this time in a sloping lupine meadow captured in early July on the brink of White River Canyon (below).

August features lupine meadows on the slopes of White River Canyon

The vastness of the White River Canyon is always an awesome thing to see, and despite the retreat of the White River Glacier, its rugged terminus is still an impressive sight, too. It’s hard to know just how far the glacier will recede with climate change upon us, but it’s fair to say that the lower extent in this photo from last summer (below) may be gone in just a few years, leaving a few moraines behind to mark its former extent.

White River Glacier is receding in a warming climate…

For September, I chose a photo of the relatively new log bridge on the Trail 400 (The Gorge Trail) over Gorton Creek (below). This handsome footbridge replaced a nearly identical version that had decayed enough to become unstable a few years ago. But the new bridge has quickly weathered to appear as if it has been here for decades, making this is one of the more photogenic spots in the Gorge. It’s rarely busy here, so also a favorite escape of mine on otherwise crowded weekends in the Gorge.

September features the Gorge 400 Trail bridge over Gorton Creek

When approaching the Gorton Creek area, this sign (below) at the entrance of the Wyeth Campground always seems odd – after all, most campgrounds in the Gorge have piped water systems from nearby springs.

Surprising sign at the Wyeth Campground…

But the story behind the water problems at Wyeth unfolds as you approach Emerald Falls, the unofficial name for the photogenic lower cascade on Gorton Creek. A 1930s-era diversion dam and pipe system at the falls has gradually been falling apart, with various jury-rigged efforts to keep the system functioning over the years.

When I visited Gorton Creek this year, the latest fix consisting of a riprap of logs (below) had been placed beneath a new section of water line leading to the campground. It’s unclear if this fix will actually restore potable water at Wyeth, but there’s apparently a renewed effort by the Forest Service to do so.

The fragile, exposed waterworks below Emerald Falls

Fall colors were surprisingly good this year, despite the devastating drought that saw many deciduous trees dropping their leaves in mid-August. By late October, however, many Gorge trails were lighting up with the familiar bright yellow displays we expect from our resident maples, including Elowah Falls (below).

October features Elowah Falls

The Elowah Falls photo is actually a 3-image, blended panorama from a long-forgotten overlook that was bypassed when the modern trails were built in the McCord Creek area. It still provides one of the finest views of the falls, but only if you know where to find the old trail!

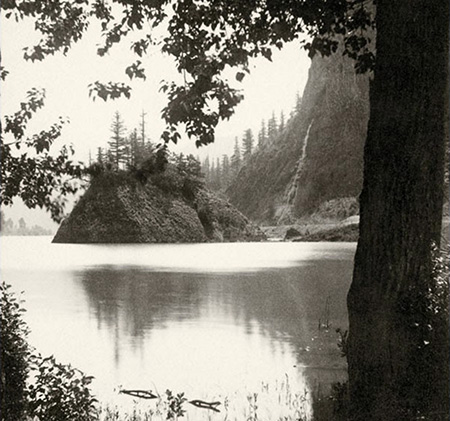

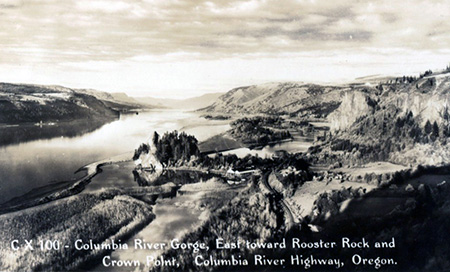

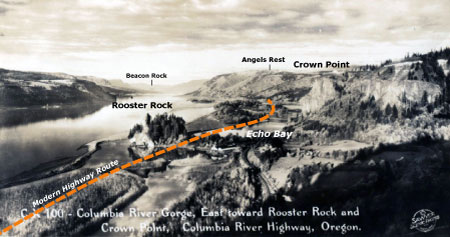

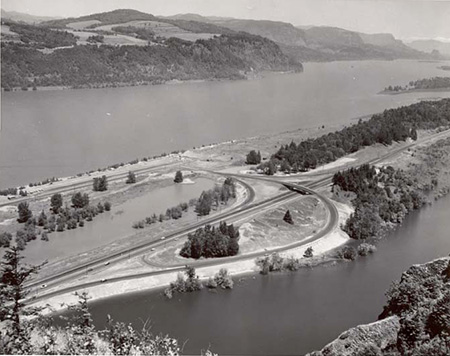

November features tunra swans at Mirror Lake, below Crown Point

For November, I selected an image from “the other” Mirror Lake described in this blog article. While I was able to capture some fall colors and even a group of tundra swans flying through the scene, my main goal in visiting this spot was to replicate an 1870s image of this same spot (below), as captured on glass slides by pioneering photographer Frank Haynes.

Echo Bay Comparison (1880s – 2015)

Click here for a larger image

I didn’t quite nail it, in part because I didn’t want to spook the abundant waterfowl resting here, and also because I was running out of dry land to walk on. But it was fun to trace the footsteps of an early photographer. Next time, I’ll try getting a bit closer to the exact spot where Frank Haynes stood by visiting outside of the migratory season for swans, geese and ducks.

For December, I picked a somewhat unconventional (for me) image of a group of mountain hemlock, noble fir and Alaska cedar near Barlow Pass after the first (and only) heavy snowfall, below.

December features a winter wonderland near Barlow Pass

But my real goal on that early snowshoe trip last winter was a different photo, the view of Mount Hood from the Buzzard Point overlook (below) along the historic loop highway. In the end, I thought I’d break from tradition and use a more intimate scene for the calendar – hopefully, you will agree, and apologies if you prefer the alpenglow scene!

Later that evening near Barlow Pass

The new calendar format offered by Zazzle also gives me the back cover of the calendar to design, and that’s a major enhancement over CafePress. I thought long and hard about what to put on the back, and ended up doing a wildflower collage (below), since close-up images of flora never make it into my calendars.

The back cover features nine of my favorite wildflower images

For the curious, the flora were taken at the following locations, starting in the upper left and working across:

Top Row:

- Vine maple near Clear lake

- Clackamas White Iris near Pup Creek Falls

- Fairy Slipper (or Calypso) orchid near Cabin Creek

Middle Row:

- Tiger lily along the Horsetail Creek trail

- Columbine near the base of Elowah Falls

- Paintbrush along the summit of Hood River Mountain

Bottom Row:

- Chocolate lily in the hanging meadows above Warren Creek

- Gentian along McGee Creek

- Maidenhair fern near Upper McCord Creek Falls

That’s it for this year’s calendar! Looking ahead toward 2016, I hope to keep up my current pace of WyEast articles as I focus more of my efforts as a volunteer for Trailkeepers of Oregon, among other pursuits. And spend time on the trail, of course!

“You know, this would make a GREAT national park!”

As always, thanks for reading this blog, and especially for the kind comments you’ve sent over the years. I’ve never felt better about Mount Hood and the Gorge someday getting the recognition (and Park Service stewardship) they deserve! That’s largely because of a passionate new generation of Millennials who are questioning the tactics and somewhat stale vision of the conservation movement’s old guard.

While it’s true that we oldsters have savvy and insight borne of experience, it’s also true that fighting too many battles can leave activists tired and resigned. So, bring on the new blood with their refreshing idealism and optimism! We are about to hand them the keys to the movement, and I very much like where they want to take us.

Happy trails to you in 2016!

Tom Kloster | Wy’East Blog