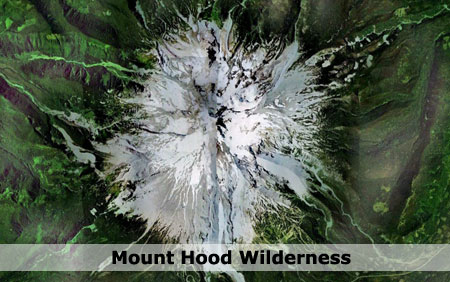

It’s no secret that mountain bikes have been relegated to second-class status when it comes to recreation trails. They’re not allowed in designated wilderness areas, and even with the special set-asides for mountain bikes called out in the recent Mount Hood Wilderness additions, the trail options around the mountain are limited.

It’s also true that bikes and hikers don’t always mix well. Since I’m both a hiker and cyclist, I’m probably more comfortable than most hikers when it comes to shared trails. I love to hike and bike the Surveyor’s Ridge Trail, for example, but most hikers shy away because of its popularity among mountain bikers.

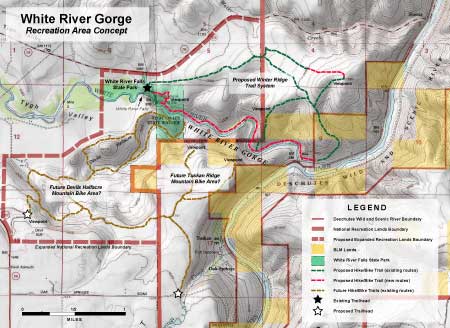

This article is a proposal for something a little different for mountain bikers: the concept is to convert fading logging roads in a scenic area directly adjacent to the Mark O. Hatfield Wilderness to become a dedicated bicycle backcountry. In addition to providing an exciting set of mountain biking trails, the concept would specifically allow for bikepacking — overnight camping at a several destinations that would be bike-in, only.

Most importantly, this new destination would be close to both Portland and the mountain biking hub of Hood River, where bicycle tourism has become an important part of the recreation economy.

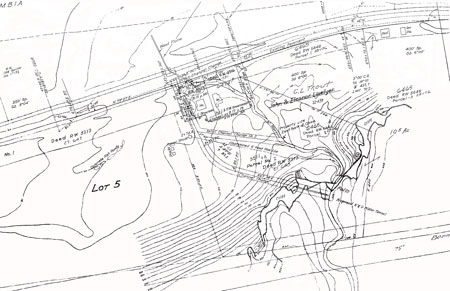

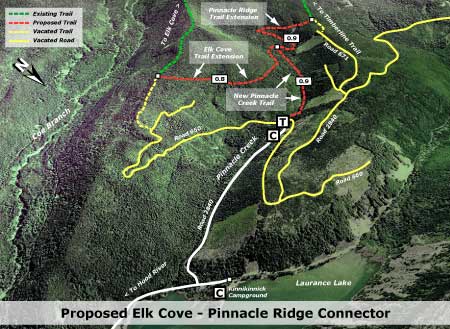

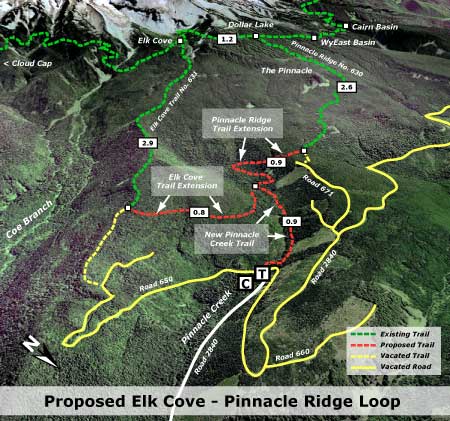

[click here for a large, printable map]

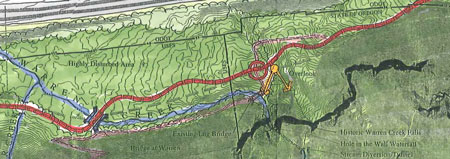

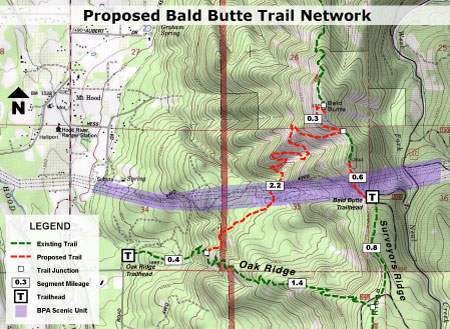

The best part of this proposal is that it wouldn’t take much to put the network together. Converting fading roads and constructing just 2.9 miles of new trail (shown in yellow on the map, above) would create a 25-mile bike network of bike-only trails (shown in blue) in an area with terrific scenery, creating as close to a wilderness experience as you can have while on two wheels.

The Proposal

The proposed bicycle backcountry would straddle the high country along Waucoma Ridge, about ten miles due north of Mount Hood. Two main trailheads would serve the backcountry: a new trailhead would be constructed in the headwaters valley of Divers Creek, serving as the primary entry into the bicycle backcountry. The existing Wahtum Lake trailhead would serve as overflow. Both are accessed on paved roads. A third, more remote trailhead would be located at the headwaters of Green Point Creek, accessed by a primitive road.

Trails

The proposed network has three kinds of bicycle facilities: converted logging roads (dashed blue on the map) functioning as single or dual track routes, new single track bike trails (dashed yellow) and striped bikeways (solid blue) on a short segment of paved Wahtum Lake Road that serves as a critical connection in the proposed network.

The focus of the network is on bicycle loop tours. From the proposed new trailhead, dozens of tour variations are possible, thanks to the dense network of old roads in this area, and the potential to connect and convert them. One out-and-back trail exists, following the Waucoma Road to Indian Mountain (under this proposal, the road would be gated to motor vehicles at the Wahtum Lake trailhead)

The main focus of the new trail system would be Blowdown Mountain, a surprisingly rugged shield volcano whose gentle summit ridge belies a rugged east face, featuring a craggy volcanic plug rising above a series of forested glacial cirques. An attractive spur road traverses the entire summit ridge of Blowdown Mountain, and would form the spine of the trail network in this part of the bicycle backcountry.

Three small lakes are located in glacial cirques on the northeast flank of the mountain, and views from the high ridges include nearby Mount Hood, to the south, and the high peaks of the Hatfield Wilderness, to the north. The big Washington State volcanoes complete the scene on the northern skyline.

The western part of the proposed network focuses on Indianhead Ridge, another high shoulder of the Waucoma Ridge complex, extending south toward the West Fork Hood River. The proposed trail network in this section would include extensive ridge top rides, with panoramic views of Mount Hood and the steep east face of Indian Mountain.

This part of the bicycle backcountry would also encompass the Waucoma Ridge Road, gating and converting the route to bike-only use except for Forest Service vehicles. The road leads through exceptionally scenic terrain, including the former lookout site on Indian Mountain, and fine views into the Eagle Creek valley, within the Hatfield Wilderness. The road, itself, forms the Hatfield Wilderness boundary.

This section of the proposal network also includes seldom-visited Scout Lake, a beautiful forest lake that has historically been stocked with brook trout by the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW).

Campsites

Five bikepacking campsites are proposed along the new trail circuit. One is simply the existing Indian Springs Campground, an excellent but largely forgotten primitive campground in need of repair. New campsites would be located at Ottertail Lake, the Talus Pond near Gray Butte, Mosquito Lake and Scout Lake, with each offering 5-15 tent sites.

Unlike the nearby Hatfield Wilderness, bikepacking campsites in the new backcountry would feature rustic picnic tables, fire rings and secure hitching racks for bicycles — features that aren’t allowed in a wilderness area, but would be welcome additions in the bicycle backcountry.

What would it take?

The viability of this proposal is in its simplicity: less than three miles of new trail would open a 25-mile network, with dozens of loop options that could be tailored to the ability of individual mountain bikers. Most of the work required could be done with the help of volunteers, from trail building and campsite development to signage and ongoing maintenance. Some heavy equipment would be required to develop the new, main trailhead and decommission vehicle access to converted roads.

Of course, the proposal would also require the Mount Hood National Forest (MHNF) to fully devote the Waucoma Ridge area to quiet recreation. A few years ago, that would have been unlikely, but in recent years, the agency has not only adopted plans to phase out hundreds of miles of logging roads, but also a policy to focus OHV use in a few, very specific areas of the forest. The recent developments could move this proposal into the realm of the possible if sufficient support exists for a bicycle backcountry.

It would take dedicated support from the mountain biking community to make the case to the Forest Service, ideally in a partnership with the agency that would include volunteer support in developing the trail system.

Cyclist on the new Sandy Ridge trail system, an example of collaboration between the USFS and bicycle advocates (City of Sandy)

The good news is that mountain bicycling organizations are already working hard to develop trails elsewhere in the Mount Hood region (such as the Sandy Ridge trail complex, pictured above) and hopefully would find this proposal worth pursuing. If you’re a mountain biker, you can do your part by forwarding this article to like-minded enthusiasts, or your favorite mountain biking organization. It’s a great project just looking for a champion!

____________

Bikepacking Resources

Bikepacking.net is an online community that focuses on off-road touring, away from cars, with great information on gear, routes and trip planning.

The Adventure Cycling Association posted this helpful article on how to pack for your bikepack trip.

Another good article on what to pack for your bikepack on the WhileOutRiding.com blog.

The International Mountain Bicycling Association is the premier organization and advocate for backcountry bicycling.

In the Mount Hood region, the Northwest Trail Alliance is the IMBA Chapter doing the heavy-lifting on bicycle trail advocacy.