[click here for a large image]

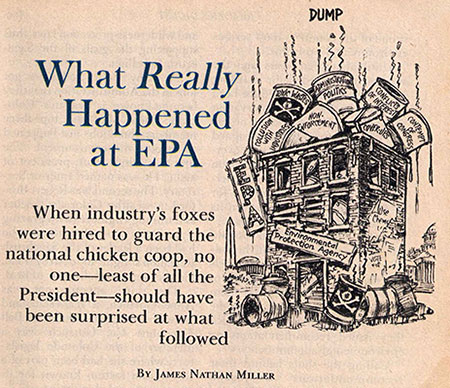

Each year since the Mount Hood National Park Campaign began in 2004, I’ve published a wall calendar to celebrate the many reasons why Mount Hood and the Columbia River Gorge should be our next national park. You can pick up a calendar here:

2017 Mount Hood National Park Campaign Calendar

The calendar sales help cover some of the costs of keeping the campaign website and WyEast blog up and running. More importantly, they ensure that I continue to explore new places in the gorge and on the mountain, as each calendar consists exclusively of photos I’ve taken in the previous year. In this article, I’ll provide some of the stories behind the photos in the new Mount Hood National Park Campaign Calendar.

The Calendar

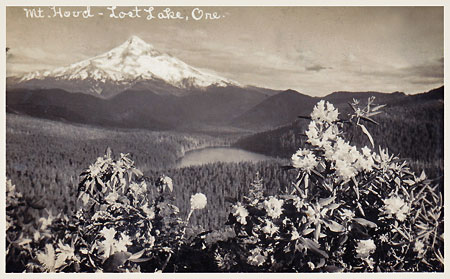

Beginning in 2016, I’ve published the calendar at Zazzle, where the quality of printing and binding is much better than my former printer. The excellent print quality shows in the front cover (above), a view of the northwest face of Mount Hood from Cathedral Ridge where the color accuracy does justice to the vibrant cliffs on this side of the mountain.

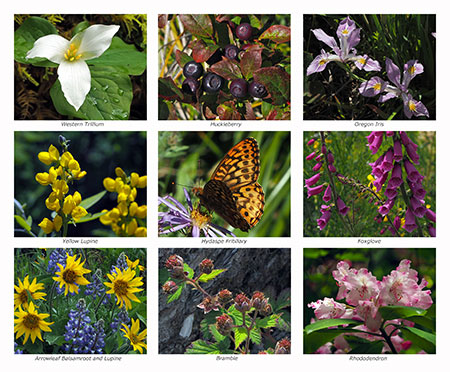

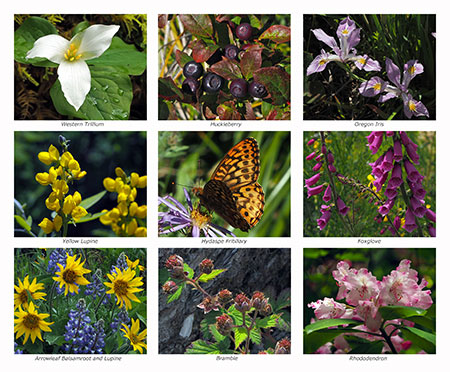

An added bonus with Zazzle is the ability to include a full-color spread on the back of the calendar. As with the 2016 calendar, I’ve used this space to show off some of the flora I’ve photographed over the past year – and this year, I added berries and a butterfly to the mix, too:

[click here for a large image]

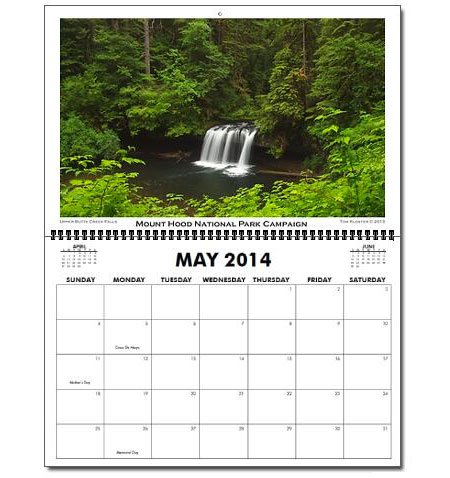

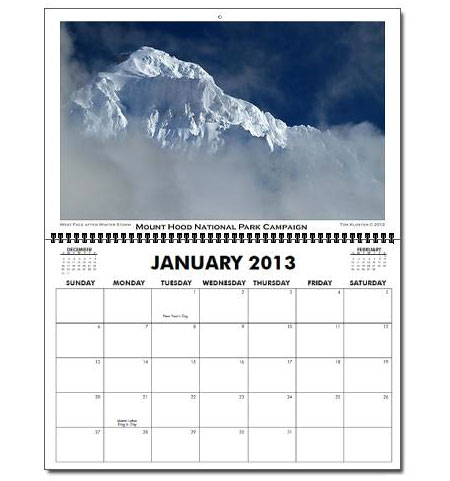

The monthly layout remains the same as last year, with a classic design that serves nicely as a working calendar for kitchens or offices:

The finished calendar hangs 14 inches wide by 22 inches tall, with a white wire binding.

The Images

The following is a rundown of the 12 images inside the calendar by month, with a link to a large version of each image, too. This year, I’ve posted especially large versions to allow for a closer look at these scenes (in a new window), and you can see them by clicking the link beneath each preview image.

The 2017 calendar begins with a chilly Tamanawas Falls for the January image. This impressive waterfall is located on Cold Spring Creek on Mount Hood’s east slope:

Tamanawas Falls in winter clothes

[click here for a large image]

This popularity of this trail in winter has ballooned in recent years, from almost no visitors just a decade ago to traffic jams on winter weekends today.

The scenery explains the popularity. While the trail is lovely in the snow-free seasons, it’s downright magical after the first heavy snows in winter. The scene below is typical of the many breathtaking vistas along the hike during the snow season.

Cold Spring Creek gets just a little bit colder

It’s still possible to have the place to yourself, however. Go on a weekday, and you’re likely to find just a few hikers and snowshoers on the trail. Thus far, no Snow Park pass is required here – though that will surely come if the weekend crowds continue!

For February, I picked an image of Mount Hood’s steep north face, featuring the icefalls of the Coe and Ladd glaciers:

Mount Hood’s mighty north face from Owl Point

[click here for a large image]

This view is unique to the extent that it was taken from the Old Vista Ridge trail to Owl Point – a route that was reopened in 2007 by volunteers and provides a perspective of the mountain rarely seen by most visitors.

For March, I selected an image of Upper Butte Creek Falls:

Lovely Upper Butte Creek Falls in spring

[click here for a large image]

This is on the margins of Mount Hood country, but deserves better protections than the Oregon Department of Forestry (ODF) can ever provide, given their constitutional obligation to log state forests to provide state revenue.

While ODF has done a very good job with the short trails that reach the waterfalls of Butte Creek, the bulk of the watershed is still heavily managed for timber harvests. Who knows, someday maybe it will be part of a Mount Hood National Park? It’s certainly worthy.

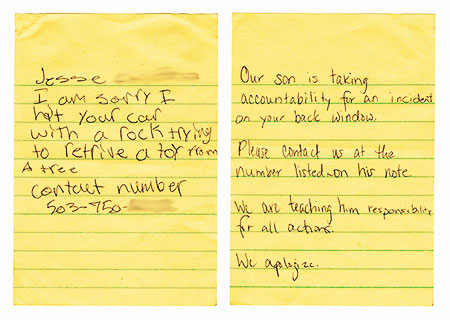

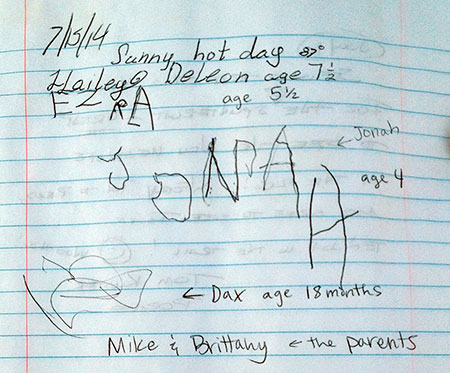

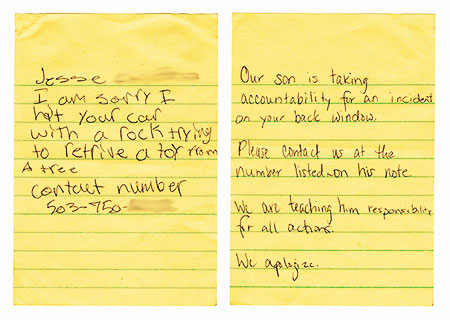

On this particular trip last spring, I returned to the trailhead to find these notes on my windshield:

Our future is in good hands!

Not much damage to the car, and the note more than made up for it! I did contact Jesse, and ended up speaking to his dad. I thanked him for being an excellent parent. With dads (and moms) like this, our future is in good hands!

For April, I picked this scene from Rowena Crest at the height of the Balsamroot and Lupine bloom season:

Rowena Crest in April splendor

[click here for a large image]

Just me and a few hundred other photographers up there to enjoy the wildflowers on that busy, sunny Sunday afternoon! Look closely, and you can see a freight train heading west on the Union Pacific tracks in the distance, lending scale to the enormity of the Gorge.

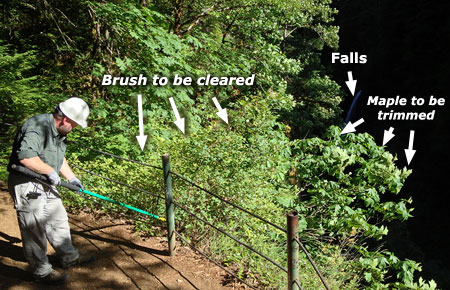

For the May image, I chose the classic scene of Punch Bowl Falls along the popular Eagle Creek Trail in the Gorge:

Punch Bowl Falls in spring

[click here for a large image]

The spring rains faded quickly this year, resulting in much lower flows along Eagle Creek by the time spring greenery was emerging, making it less chilly to wade out to the view of the falls. To the right of the falls you can also see the latest downfall to land in front of the falls. To my eye, this adds to the scene, so I see it as a plus.

This isn’t the first big tree to drop into the Punch Bowl in recent years. In the mid-2000s, another large tree fell directly in front of the falls, much to the frustration of photographers:

Punch Bowl Falls in 2006 with an earlier fallen tree in front of the falls

That earlier tree was flushed out a few years ago, only to be replaced by the current, somewhat less obtrusive downfall a couple of years ago. Here’s a wider view showing this most recent addition, including the giant root ball:

Gravity at work once again at Punch Bowl Falls

This pattern will continue as it has for millennia, as other large Douglas fir trees are leaning badly along the rim of the Punch Bowl. They eventually will drop into the bowl, too, frustrating future generations of photographers!

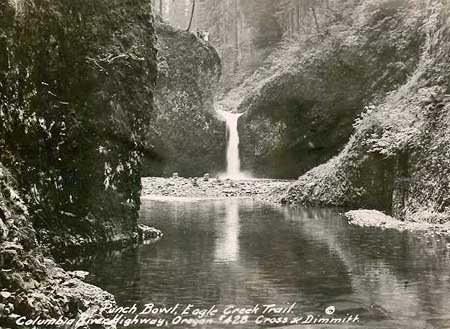

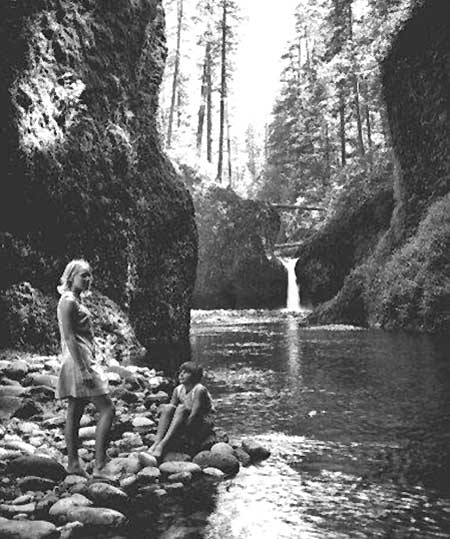

The Punch Bowl, itself, changes over time. This early view from the 1920s shows a lot more debris inside the bowl compared to recent decades, possibly from erosion that followed an early 1900s forest fire in the Eagle Creek canyon:

Punch Bowl Falls in the 1920s

Look closely and you can see flapper-era hikers on the rim of the bowl and several rock stacks left by visitors on the gravel bar – some things never change!

The June image in the new calendar is the opposite of Punch Bowl Falls. While thousands visit Eagle Creek each year, the remote spot pictured below is rarely visited by anyone, despite being less than a mile from Wahtum Lake and the headwaters of Eagle Creek. This view is from a rugged, unnamed peak along Waucoma Ridge, looking toward another unnamed butte and snowy Mount Adams, in the distance:

A place of ancient significance, yet lost in our modern time

[click here for a large image]

For the purpose of keeping track of unnamed places, I’ve called the talus-covered butte in the photo “Pika Butte”, in honor of its numerous Pika residents. The peak from which the photo is taken is an extension of Blowdown Ridge, a much-abused, heavily logged and mostly forgotten beauty spot that deserves to be restored and placed under the care of the National Park Service.

The view of “Pika Butte” was taken while exploring several off-trail rock knobs and outcrops along Blowdown Ridge, but what made this spot really special was stumbling acxross a cluster of Indian pits (sometimes called vision quest pits). One pit is visible in the lower left corner of the wide view (above) and you can see three in this close-up view from the same spot:

If only these stones could tell us the story behind the mystery!

Nobody really knows why ancient people in the region made these pits, but it’s always a powerful experience to find them, and imagine the lives of indigenous peoples unfolding in the shadow of Mount Hood. These pits had a clear view of the Hood River Valley, with the Columbia River and Mount Adams in the distance. Indian pits often feature a sweeping mountain or river view, adding to the theory that they were built with a spiritual purpose.

For July, another photo from Owl Point along the Old Vista Ridge trail. This wide view shows some of the beargrass in bloom on the slopes of Owl Point on a sunny afternoon in July:

Mount Hood fills the skyline from Owl Point

[click here for a large image]

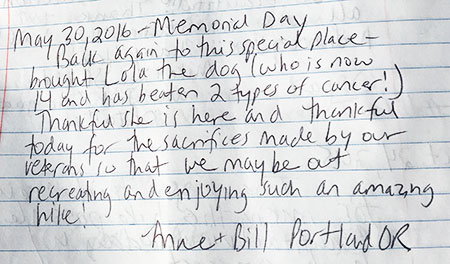

Since this historic trail was adopted by volunteers in 2007, it has become increasingly popular with hikers. Several geocaches are located along the way, as well as a summit register at Owl Point with notes from hikers from all over the world. A few recent entries among hundreds in the register show the impact that this amazing “new” view of Mount Hood has on visitors to Old Vista Ridge:

In a few months I’ll share some exciting news about the Old Vista Ridge Trail, Owl Point and the surrounding areas on Mount Hood’s north slope. Stay tuned!

For August, I picked another scene on the north side of the mountain, this time at iconic Elk Cove along the Timberline Trail:

Swale along Cove Creek in Elk Cove

[click here for a large image]

The hiker (and his dog) approaching me in this photo stopped to chat, and I was surprised to learn that he was a regular reader of this blog!

As we talked about the changes to the cove that came with the 2011 Dollar Lake Fire (that burned the north and west margins of the cove), he mentioned finding the foundation from the original Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) shelter in the brush near Cove Creek! We crossed the creek and in a short distance, came to the unmistakable outline of the shelter:

The old Elk Cove shelter foundation is surprisingly intact – but hidden

This structure was once one of several along the Timberline Trail, but fell into disrepair following avalanche damage sometime in the 1950s or early 1960s. This image is apparently from the mid-1960s, showing the still somewhat intact ruins of the shelter:

The beginning of the end for the Elk Cove shelter in the 1960s

The location of the shelter was a surprise to me, as I had long thought the building was located near a prominent clearing and campsite near the middle of Elk Cove. Now that I know the exact location, I plan to reproduce the 1960s image on my next trip to the cove, for comparison.

For September, I chose a quiet autumn scene along Gorton Creek, near the Wyeth Campground in the Columbia Gorge (below). This is a spot I’ve photographed many times, just downstream from popular Emerald Falls:

Pretty Gorton Creek in the Wyeth area of the Gorge

[click here for a large image]

This area has a fascinating history, as today’s Wyeth Campground is located on the grounds of Civilian Public Service Camp No. 1, a World War II work camp for conscientious objectors. The men serving at this camp built roads and trails throughout the Gorge, in addition to many other public works projects. The camp operated from 1941-1946. You can learn more about the Wyeth work camp here.

The October scene is familiar to anyone who has visited the Gorge. It’s Multnomah falls, of course, dressed in autumn colors:

A bugs-eye view of Multnomah Falls?

[click here for a large image]

If the photo looks different than your typical Multnomah Falls view, that’s because I blended a total of eight images to create a horizontal format of this very vertical falls to better fit the calendar. Here’s what the composite looked like before blending the images:

To young photographers of the digital age, blending photos is routine. But for those of us who started out in the age of film photography and darkrooms, the ability to blend and stack images is nothing short of magical – and fun! While younger photographers are increasingly exploring film photography as a retro art, the digital age is infinitely more enjoyable than the days of dark rooms, chemicals and expensive film and print paper for this photographer.

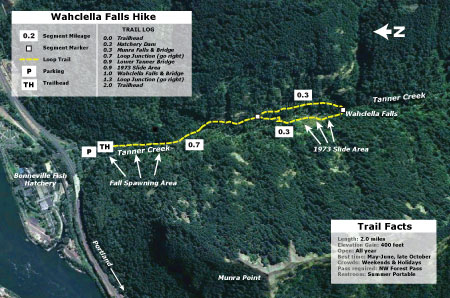

I paused before including a winter-season photo of Wahclella Falls for the November calendar image (below). Why? Because I’ve used a photo from this area in nearly every calendar since I started assembling these more than a decade ago. It’s my favorite Gorge hike – I visited Tanner Creek and Wahclella Falls five times in 2016 – and have photographed this magnificent scene dozens of times, and yet it never gets old.

Wahclella Falls is a winter spectacle!

[click here for a large image]

I decided to include this Wahclella Falls scene because it captured a particularly wild day on Tanner Creek last winter. The stream was running high, filling the canyon with mist and seasonal waterfalls drifted down the walls of the gorge on all sides.

The huge splash pool at the base of the falls was especially wild – more like ocean surf than a Cascade stream, and if you look closely, you can also see a hiker braving the rain and cold to take in this view:

Roaring falls, big boulder… and tiny hiker

I also liked the turbulent stream below the falls, which also boiled more like ocean surf than a mountain stream:

Tanner Creek comes alive in winter

So, another calendar featuring Wahclella Falls? Yes, and it certainly won’t be the last. This is among the most magical places in the Gorge – or anywhere!

Finally, for the December image I selected a photo from my first official attempt at capturing the Milky Way over Mount Hood. This view is across Laurance Lake, on the north side of the mountain:

Milky Way rising over Laurance Lake and Mount Hood

[click here for a large image]

The glow on the opposite side of the lake is a campfire at the Kinnikinnick Campground, and was just a lucky addition to the scene. While we waited for the Milky Way to appear, there were several campers arriving, making for some interesting photo captures. With a 30-second exposure set for stars, this image also captures the path of a car driving along the south side of the lake to the campground:

Headlights and campfires in a Laurance Lake time exposure

My tour guide and instructor that evening was Hood River Photographer Brian Chambers, who I profiled in this WyEast Blog article in June. Thanks for a great trip, Brian!

The author with Brian Chambers somewhere under the Milky Way

So, if you’re looking to support the blog and Mount Hood National Park campaign or just have an ugly fridge to cover, you can order the new calendar on Zazzle.

_________________

…and finally, given the unusual events in our recent national election, some reflections on what it might mean for Mount Hood and the Gorge…

Post-election deju vu: back to the future..?

Viewed through the lens of protecting public lands and the environment, the presidential election results on November 8 are discouraging, at best. For those of us who have voted in a few elections, it feels a lot like the Reagan Revolution of 1980.

So, the following is a bit of speculation on what lies ahead based upon what we’ve been through before, but with the caveat that unlike that earlier populist surge against government, the environmental agenda of the coming Trump administration is somewhat less clear and appears less ideologically driven.

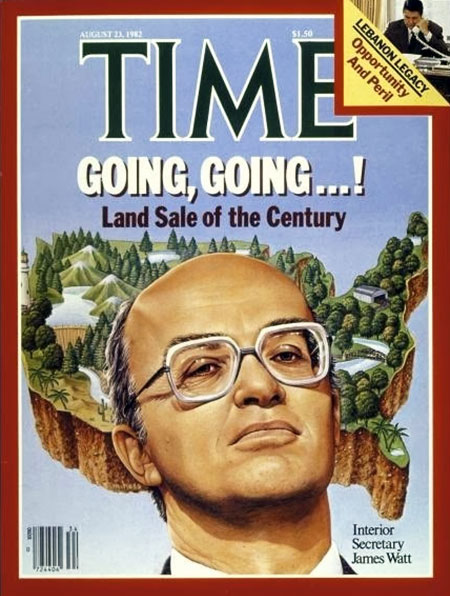

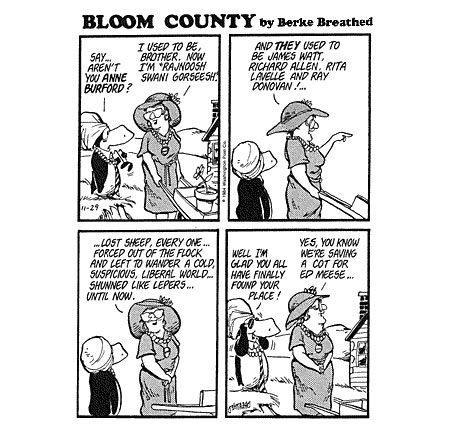

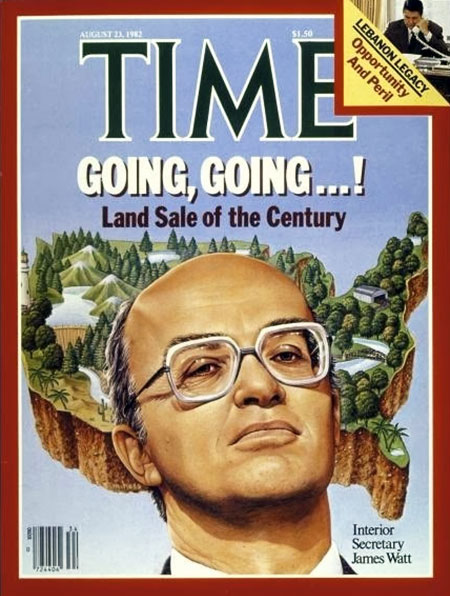

Ronald Reagan’s vision for government brought a very specific mission to dismantle environmental regulations and open up public lands to commercial interests. To carry out the mission, President Reagan appointed the highly controversial James Watt to head the Department of Interior, and the nearly as controversial Anne Gorsuch to run the EPA. John Block was tapped to head of the Department of Agriculture (which oversees the U.S. Forest Service). Watt and Gorsuch were attorneys, Block a farmer who had entered politics as an agriculture administrator in the State of Illinois.

James Watt’s radical vision for our public lands threatened to derail Ronald Reagan in his first term

Watt and Gorsuch became infamous for their open disdain for conservationists and the agencies they were appointed to administer. Watt was the Reagan administration’s sympathetic gesture to the original Sagebrush Rebellion. Block focused primarily on an ideological rollback of farm subsidies and programs that dated to the Dust Bowl, and that would eventually be his downfall.

The important lesson is that all three rode in with a “revolution” mandate, and over-reached in their zeal to rewrite American policy overnight. The blowback was instant, and though they did harm our conservation legacy during their embattled tenures, they didn’t have the lasting impact many had feared. Both Watt and Gorsuch were forced to resign before the end of President Reagan’s first term, and Block resigned in the first year of Reagan’s second term.

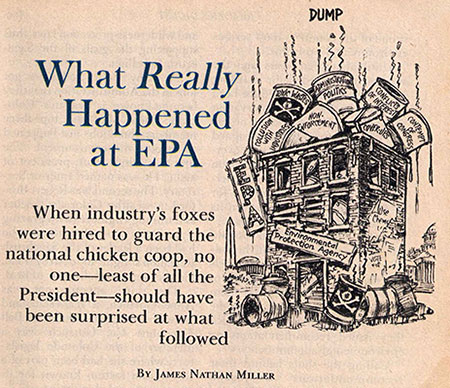

Even Readers Digest covered the EPA Superfund scandal that drove Anne Gorsuch out of office!

Gorsuch was eventually pushed out by Reagan for attempting to conceal EPA Superfund files from Congress as part of an unfolding scandal, becoming the first agency head to be cited for contempt of Congress. Before the scandal drove her from office, Gorsuch became Anne Gorsuch Burford when she married James Burford, Reagan’s Bureau of Land Management (BLM) chief, further fueling concern about whether environmental protections could be objectively enforced on BLM lands.

John Block lasted five years, but was pushed out in early 1986 as the worst farm crisis since the Great Depression unfolded under his tenure. Watt left in more spectacular fashion after stating (apparently a joke) that an ideally balanced advisory panel would include ”a black, a woman, two Jews and a cripple.” (and in the age of Google, he has been deservedly forgotten, with the more consequential James Watt – inventor of the steam engine – reclaiming his name in history).

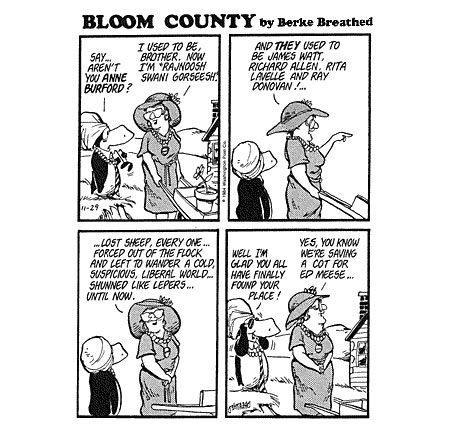

Bloom County has some fun with Oregon’s Rajneeshee saga… and Ronald Reagan’s failed cabinet appointees

Will history repeat itself? We’ll see, but there is no reason to assume that the conservation community – and, importantly, the American public – will be any less motivated to speak out if the Trump administration attempts a similar rollback on public land and environmental protections to what the Reagan Administration attempted.

Yes, there will be lost ground, but there will also be unexpected gains. That’s our system. Recall that the same President Reagan who brought James Watt to the national stage also signed the Columbia River Gorge Scenic Area Act into law thirty years ago, on November 17, 1986 (famously “holding his nose”, in his words). In his first term, President Reagan signed the Oregon Wilderness Act into law on June 26, 1984, creating 22 new wilderness areas covering more than 800,000 acres.

As President Obama said in his reflection on the election, “democracy is messy”. He also reminded the president-elect that our system of governance is more cruise ship than canoe, and that turning it around is a slow and difficult process, no matter what “mandate” you might claim. That is by design, of course.

…and the WyEast Blog in 2017..?

Looking ahead toward 2017, I hope to keep up my current pace of WyEast Blog articles as I also continue my efforts as board president for Trailkeepers of Oregon, among other pursuits. And spend time on the trail, of course!

The author somewhere in Oregon’s next national park…

As always, thanks for reading the blog, and especially for the kind and thoughtful comments many of you have posted over the years. The blog is more magazine than forum, but I do enjoy hearing different perspectives and reactions to the articles.

Despite the election shocker this year, I’ve never felt better about Mount Hood and the Gorge someday getting the recognition (and Park Service stewardship) they deserve! That’s because of a passionate new generation of conservations are becoming more involved in the direction of our nation and our public land legacy. The 2016 election seems to have accelerated the passion this new generation of stewards brings to the fight.

Our future is in very good hands, indeed.

See you on the trail in 2017!

Tom Kloster | Wy’East Blog