The first part of this article focused on the missed opportunity to restore Warren Falls as part of construction of the most recent phase of the Historic Columbia River Highway (HCRH) State Trail. This article takes a look at this newly completed section of trail.

_________________

Congressman Peter DeFazio at the grand opening of the new HCRH segment in October (ODOT)

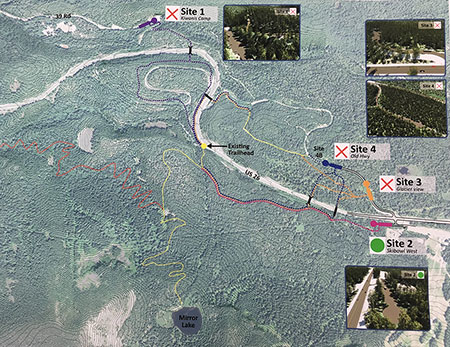

In October, the Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) opened the latest section of the HCRH State Trail, a segment stretching from the trailhead at the Starvation Creek wayside west to Lindsey Creek. A portion of this newest section follows the original highway grade where it passes Cabin Creek Falls, but most of the route is a completely new trail – or more accurately, a paved multi-purpose path open to both hikers and cyclists.

The newly revamped Starvation Creek Trailhead

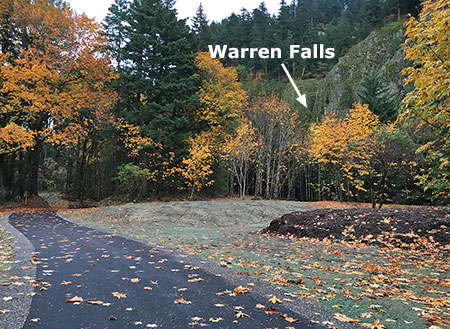

The new HCRH trail segment begins in a small plaza constructed at the south edge of the Starvation Creek wayside. Early plans called for a complete reconstruction of the parking area, but budget constraints intervened, and most of the work here is along the margins of the existing parking lot. The trailhead plaza features some to-be-installed interpretive signs in the shade of a group of bigleaf maple trees, a pleasant meeting spot for hikers or cyclists.

Missing from the revamped trailhead is the original Forest Service trailhead sign that once pointed to Warren Falls (below). It’s unclear if this sign will be reinstalled, but given that Warren Falls, itself, was not “reinstalled” as part of this project, the chances are probably slim.

This sign has gone missing!

The sign actually referred to what is now called Hole-in-the-Wall Falls, where Warren Creek emerges from the diversion tunnel built by ODOT in 1939. The unintended reference to the original falls made for an inspiring Forest Service gaffe for advocates of restoring Warren Falls!

The first few yards of the new trail generally follows the existing route along the Starvation Creek wayside freeway exit ramp. It’s still a noisy, harsh walk through this area, but ODOT has dressed up this section with a sturdy cobble wall and new paving.

Cobble retaining wall near Starvation Creek

The trail concrete barricades along this section that protect the trail from freeway traffic also feature the same decorative steel fencing found elsewhere on the HCRH State Trail, giving a bit more sense of separation from speeding vehicles. The new trail is also slightly elevated here, reducing the noise impacts somewhat from the old trail that was mostly at the ramp grade.

Decorative steel fencing near Starvation Creek

Soon, the new trail drops to the only original section of Columbia River Highway on this restored section of trail, where the old road passed in front of Cabin Creek Falls. An elegant but confusing signpost has been added at the junction with the Starvation Ridge Cutoff trail, pointing to Gorge Trail 400, which currently does not exist in this section of the Gorge.

I didn’t hear back from ODOT as to whether a trail renumbering is in the works that would extend the Gorge Trail to Starvation Creek, but it may be that the Forest Service is planning to stitch together a extension of the Gorge Trail from pieces of the Starvation Ridge and Defiance Trails. That would be a welcome development!

Trail 400..? Is a trail re-numbering in the works?

The location of the new sign almost suggests that the infamous Starvation Cutoff trail – one of the steepest in the Gorge – would be renumbered as the Starvation Ridge trail, with the bypassed section of the current Starvation Ridge trail becoming Trail 400.

Confused..? So are many hikers who visit the area with its already confusing trail network. So, keep your fingers crossed that the Forest Service is rethinking trail numbers and signage in conjunction with the new HCRH trail.

For now, the actual Starvation Cutoff Trail has not changed, though HCRH workers added a nice set of steps at the start of this very steep route.

New steps at the otherwise humble Starvation Cutoff trailhead

The old pavement in this original highway section was resurfaced with new asphalt as part of the project, but otherwise the route here is much as it was when the highway opened in 1916, including a roadside view of Cabin Creek Falls. However, ODOT missed an opportunity to organize the hordes of visitors who now scramble to the falls along a cobweb of boot paths.

Formalizing a single spur with a properly constructed trail (below) would be a great project for a non-profit like [link]Trailkeepers of Oregon (TKO)[/link] in conjunction with Oregon Parks and Recreation (OPRD), who now manage the trail and adjacent park lands.

Cabin Creek could use a formal path to the falls… and a new sign

[click here for a large version]

Cabin Creek Falls is popular with families (where kids can safely play in the basalt-rimmed splash pool) and photographers (who love this delicate, mossy falls). For many casual visitors, this is already the turn-around point on their walk from the trailhead, with Cabin Creek being the highlight of their experience, so a spur trail would be a nice addition to allow visitors to get off the pavement and explore a soft trail.

Cabin Creek Falls up close

ODOT also cleaned out the large, stone culvert (below) where Cabin Creek flows under the HCRH State Trail. This display of original dry masonry was mostly buried in debris and undergrowth until the trail project was constructed, so the restoration provides a nice look at the craftsmanship of the original highway.

Original dry masonry culvert survives at Cabin Creek

As the new trail route reaches the west end of the original highway section, ODOT thoughtfully place a small memorial (below) in the paving – a nice historic reference to the original highway.

HCRH plaque marks the original highway route near Cabin Creek Falls

As the new route leaves the beautiful, forested section of original highway at Cabin Creek, it suddenly follows the freeway for about 200 yards due to steep slopes along the Gorge wall. This jarringly noisy section could use some replanting to at least create a visual buffer from freeway traffic.

Noisy, barren stretch of the new trail west of Cabin Creek

Soon, the new HCRH route thankfully curves back into the forest on a surprisingly massive structured fill. This structure was required to maintain the modest trail grade as the route climbs from the freeway shoulder to a slight rise near Warren Creek.

This section is bordered with stained wood guardrails, a new design that departs from the vintage-style white guardrails in other sections of the restored highway, but provides a nice aesthetic that will also be easier to maintain.

This large, structured fill west of Cabin Creek was required to maintain the trail grade for bicycles

This following view shows the same spot in July, at the height of construction, and before the fill was completed:

Structured fill near Cabin Creek during construction last July

ODOT was careful to document cultural resources along the route when designing the new trail, including a set of stone ovens built by the original highway masons who camped here during highway construction in the early 1900s. The historic ovens are better protected than before by the raised trail design and guardrails (below), though still fully visible for those who know what they’re looking for.

The historic stone ovens can be seen from the elevated trail section west of Cabin Creek… if you know where to look

One disappointing detail along this section of trail is a long gabion basket wall (below), apparently constructed to catch loose debris from an adjacent slope. The steel cages holding this wall together will hopefully be covered in moss and ferns in time, but for now it’s an eyesore on an otherwise handsome section of the trail.

Would Sam Lancaster have approved of a wire mesh gabion wall..?

Another sore thumb in this forest section is a rusty mesh fence (below) along the freeway right-of-way that should have at least been painted, if not completely replaced as part of the project. Maybe ODOT still has plans to replace this eyesore?

Nope, Sam Lancaster wouldn’t go for this…

As the new section of the HCRH State Trail approaches Warren Creek, it enters a significant cut section to maintain its gentle grade. Thankfully, a huge anthill along this section was spared, one of the interesting curiosities along the former soft trail that used to pass through this forest.

Hydro-seeded cut slope and the big anthill near Warren Creek

This following view is from July, when construction was still underway and the ant colony was no doubt thankful for the protective fence:

The giant anthill lives!

The view below was taken during the construction looks east at the cut section along the new trail. Because the rustic forest trail that once passed through this area was completely destroyed by the new HCRH trail, the reconfigured landscape will be a shock for hikers who hiked the trail in the past. Though hydro-seeded with grass, this section could benefit from some re-vegetation efforts to further speed up healing.

The cut grade near Warren Creek under construction in July

Beyond the cut section, the new route crosses the original channel of Warren Creek, and for those with a sharp eye, a pair of cobble foundations for early homesteads that once lined the creek. Here, the trail reaches a half-circle bench where an all-access side trail curves up to the viewpoint of Hole-in-the-Wall Falls (more on that later in this article).

Half-circle bench serves as the jump-off point to the Hole-in-the-Wall viewpoint

It’s unclear if interpretive signs will be added to this area, but at one time the story of how Warren Creek was diverted in 1939 was planned for the spot where the new trail crosses the old, dry creek bed.

Another new trail sign is also located at the all-access spur trail to Hole-in-the-Wall Falls, as this is also the route to the Starvation Ridge and Defiance Trails. This sign also includes a mysterious reference to Gorge Trail 400, further suggesting that a re-numbering of trails in the area is in the works. A large, multi-trunked bigleaf maple was also spared at this junction.

Bigleaf maple spared… and another mystery reference to Trail 400..?

The following view is looking from the new HCRH State Trail toward the Hole-in-the-Wall spur trail, showing the proximity to Warren Falls. The green hydro-seeded area in the photo is where the construction staging area for the project, underscoring the missed opportunity to restore Warren Falls as part of the project – it was just a few yards beyond the staging area.

So very close: Warren Falls from the main construction staging area

Staging area during construction in July – the last time we’ll see heavy equipment this close to Warren Falls for generations?

The humble elderberry (below) in the middle of the staging area was spared by ODOT, a nice consideration in a project that did impact a lot of trees. Hopefully, there are plans to expand native plantings here, as this area was covered with invasive Himalayan blackberries for decades before the trail project and will surely revert to invasive species without a deliberate restoration effort.

This apparently well-connected elderberry dodged the ODOT bulldozers!

Moving west, the new HCRH State Trail segment passes through another forested section where the trail rises on fill necessary to bring it to grade with a handsome new bridge over Warren Creek (visible in the distance in the view, below). This is an especially attractive section of trail.

Looking west along the attractive new trail section approaching the Warren Creek Bridge

For some reason, many of the trees that were cut for this new section of trail were left piled along the base of the fill (below). The fill slope has been hydro-seeded, so it seems unlikely that the more work is planned to remove or repurpose the log piles, so apparently the were left in this manner on purpose?

Piled logs along the elevated grade approaching Warren Creek Bridge

Looking back to the construction period last summer, you can also see the good work ODOT did to cut back English ivy that was rampant in this area. While ivy was left intact on the forest floor, it was cleared from dozens of trees in this section of the trail.

Invasive English ivy was trimmed from dozens of trees near Warren Creek

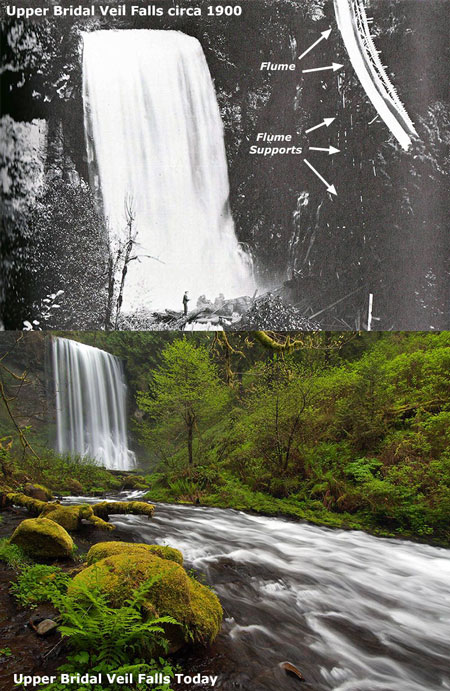

The highlight of the new HCRH trail segment is where the route crosses Warren Creek. Here, a handsome new bridge faithfully echoes the design ethic of Samuel Lancaster, but is probably more elaborate than the original bridge constructed at Warren Creek in 1916. Lancaster’s bridge was destroyed when the first version of the modern highway was built in 1950.

The handsome new Warren Creek Bridge is the jewel of the new trail segment

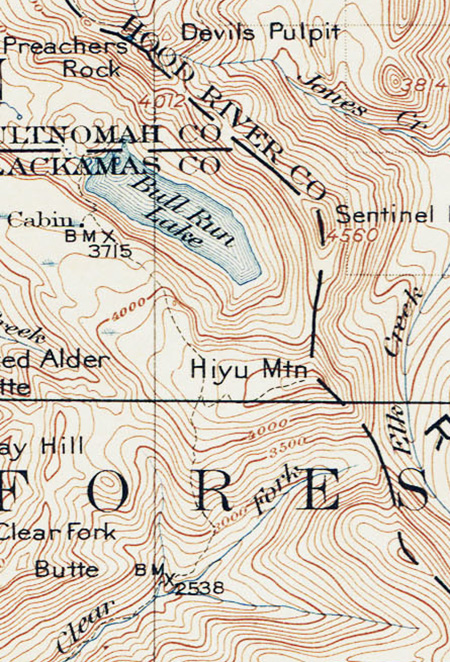

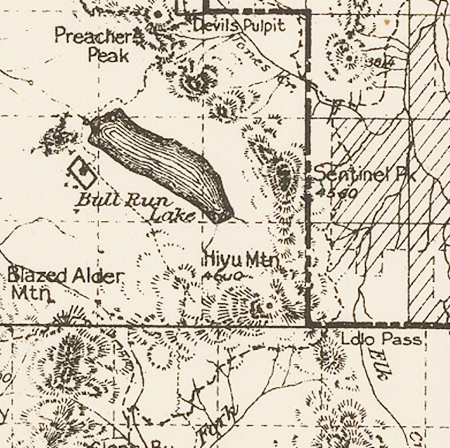

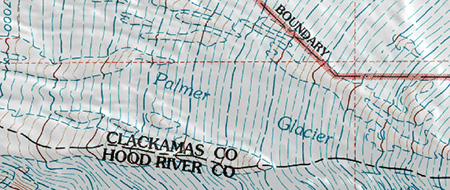

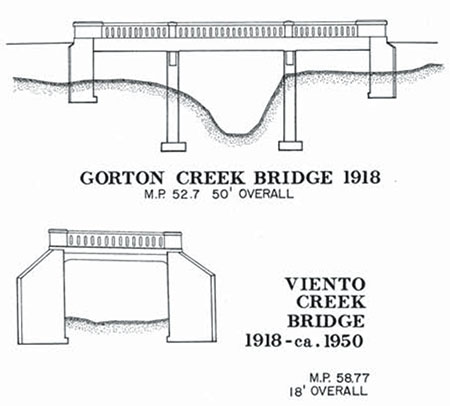

Though no visual record exists, the original Warren Creek Bridge was modest in length, at just 18 feet, and likely resembled the surviving bridge at Gorton Creek to the west, or possibly the original bridge at Viento Creek to the east (shown below).

The original Warren Creek Bridge probably followed one of these designs

The design of the original Warren Creek Bridge inadvertently helped lead the Highway Department to bypass Warren Falls, as stream debris was clogging the bridge opening. The 1941 project files also describe the original bridge being “replaced in a different location” as part of the diversion project, so there may have been two version of the original bridge over Warren Creek before the modern highway was constructed in the 1950s.

Warren Creek Bridge under construction in July

Pavement texture samplers being tested for the project

Looking west across the new Warren Creek Bridge

Railing detail and the view downstream from Warren Creek Bridge

Construction of the new HCRH bridge over Warren Creek was an involved undertaking, with the surprisingly wide span leaving plenty of room for a (someday) restored Warren Falls to move 70+ years of accumulated rock and woody debris down the stream channel.

Built to last, with plenty of room for Warren Creek to once again move rock and log debris down its channel… someday…

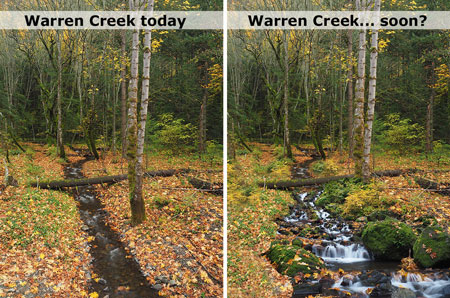

There’s nothing natural about Warren Creek in this area, as it looks (and is) more like a drainage ditch. This is because original streambed is now a dry ravine several hundred yards to the east, and the current streambed is where the Highway Department moved the creek decades ago, when the modern highway was first built in the 1950s.

Ditch-like, man-made channel of Warren Creek as viewed from the new bridge

As described in the first part of this article, the someday restoration of Warren Falls will once again allow rocks and woody debris to migrate into the lower channel, eventually transforming the “ditch” into a healthy stream (below) that can fully support endangered salmon and steelhead.

What a healthy Warren Creek might look like from the bridge, someday…

[click here for a larger version]

While ODOT missed the larger opportunity to help this stream restoration along when it declined to restore Warren Falls, the agency also missed the easy opportunity to simply add a few boulders and logs to the section of Warren Creek near the bridge when heavy equipment was in the area. That’s too bad, but perhaps the OPRD will someday enhance this stream section as part of managing the new trail.

Looking west from near the Warren Creek Bridge to the Lancaster Falls viewpoint

From Warren Creek, the new trail follows another fill section to a mostly obstructed viewpoint of Lancaster Falls on Wonder Creek from a small seating area. This viewpoint (below) could use some light pruning to reveal the falls, and perhaps something that’s still in the works by OPRD.

Lancaster Falls viewpoint

One oddity about Wonder Creek is that it mostly disappears into ground before reaching the culvert that carries Warren Creek under I-84 and to the Columbia River. This is partly due to the modest flow from spring-fed Wonder Creek, but also because the slopes below the falls are mostly composed of unconsolidated talus covered with a thin layer of soil and vegetation. So, most of the time the stream is simply absorbed into the water table below the falls.

Yet, in high runoff periods, the new state trail will accommodate the flow with extensive drainage features designed to carry Wonder Creek under the fill section and to the Warren Creek freeway culvert.

Trail construction near the Lancaster Falls viewpoint in July

Lancaster Falls viewpoint under construction in July

Another oddity of Lancaster Falls is its illusive nature. Though thousands of hikers each year view the modest, 20-foot lower tier of the falls where it spills across the Defiance Trail, few know of it’s full extent – and perhaps wonder why Samuel Lancaster wasn’t honored with a more spectacular landmark.

This is the view (below) of Lancaster Falls that most hikers see today, and this this is also the portion of the falls that can be glimpsed through the trees from the new HCRH trail viewpoint:

Lancaster Falls as most know it, along the Defiance Trail

But viewed from across the Columbia River, along Washington’s Highway 14, Lancaster Falls takes on a completely different scale. This view shows the lower 20-foot tier that most know as “Lancaster Falls” completely dwarfed by the towering 300-foot extent of the falls:

The full extent of Lancaster Falls as viewed from the Washington side of the Columbia

While it’s possible to scramble to the base of the main tier of Lancaster Falls, the slopes are unstable and already being impacted by off-trail visitors, so it’s probably best that only a most portion of the falls is (somewhat) visible from the new HCRH route. Hopefully, interpretive signage is in the works for the viewpoint that tells the story of Samuel Lancaster..?

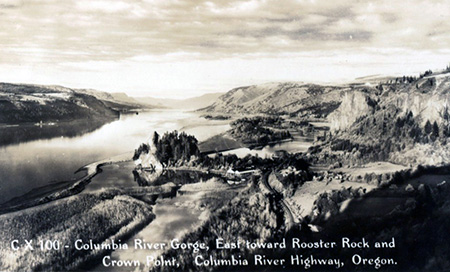

1920s view of the HCRH from Lindsey Creek looking toward Wind Mountain

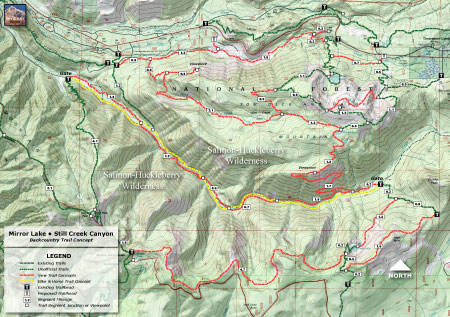

From the Lancaster Falls viewpoint, the new trail heads west to a section where it once again follows the shoulder of I-84 to Lindsey Creek and the end of new construction. ODOT is working the next trail segment, which will connect from Lindsey Creek to the Wyeth Campground, crossing the base of famously unstable Shellrock Mountain along the way.

Hole-in-the-Wall Falls Spur Trail

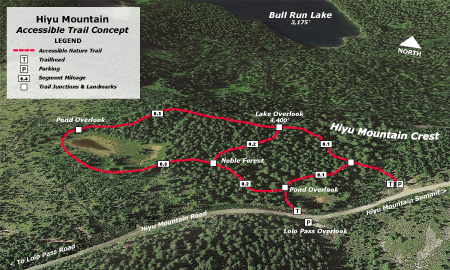

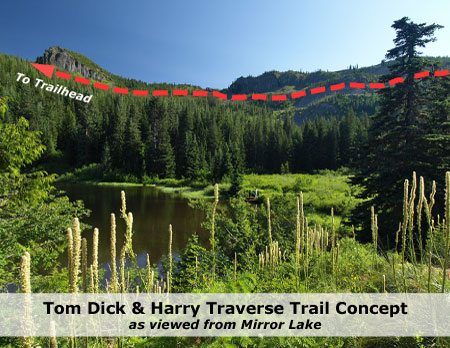

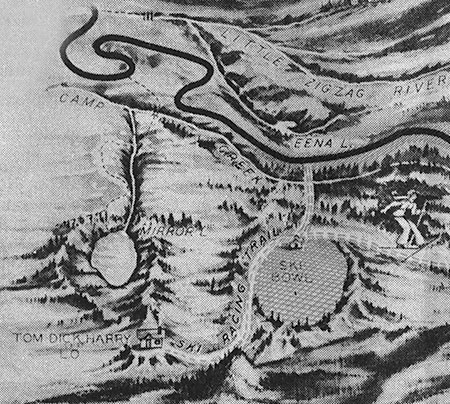

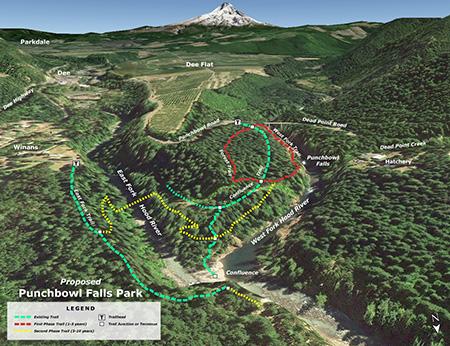

Original concept for the Hole-in-the-Wall Falls viewpoint

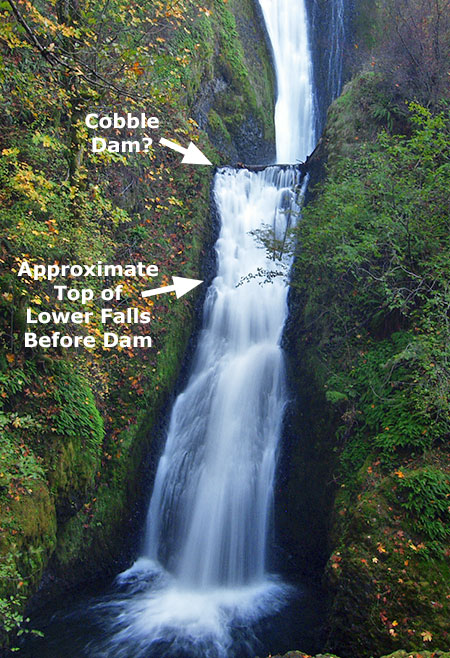

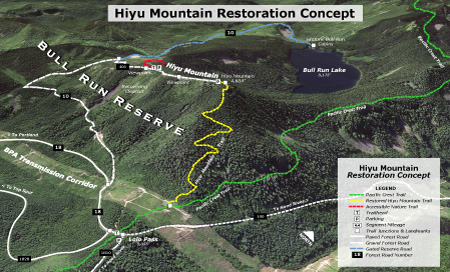

One of the design highlights of the new HCRH trail section is a short all-access spur tail to an overlook of Hole-in-the-Wall Falls, the man-made outflow tunnel that continues to drain Warren Falls of its water. The completed overlook has been scaled back from its original design (shown above), and now features one of the signature circular seating areas, complete with a picnic table (below).

Hole-in-the-Wall Falls viewpoint

A small plaque at the viewpoint identifies Hole-in-the-Wall Falls, which until now has not been an officially recognized name or has appeared on any official maps. A nice nod to the origin if the “falls” is the byline “Created 1939”. Hopefully, there will be future interpretive displays here, as the story of Warren Falls would be a great addition to this overlook.

Hole-in-the-Wall Falls viewpoint

Hole-in-the-Wall Falls plaque

Hole-in-the-Wall Falls viewpoint under construction in July

The Starvation Ridge Trail picks up from the south side of the Hole-in-the-Wall Falls overlook, heading across a footbridge over Warren Creek.

A closer look near the footbridge (below) reveals a surprising disappointment: the stump of a streamside Douglas fir cut improve the view of the falls. It’s too bad that the tree wasn’t simply limbed to provide a view, as it was one of the few larger trees stabilizing the banks of Warren Creek.

Hole-in-the-Wall Falls bridge… and stump?

Unfortunate remains of the offending Douglas fir along Warren Creek

While it’s disappointing to think about the opportunities missed at Warren Falls, the Hole-in-the-Wall Falls overlook and beautiful new Warren Creek Bridge, are still a big a step in the right direction toward someday moving Warren Creek from neglected afterthought to a valued resource that deserves to be restored. ODOT deserves major kudos for their thoughtful work on this section of trail!

“Love what they’ve done with the place…”

Heavy construction of the new “trail” in July looked more like a road to many hikers

Last summer I encountered another hiker while surveying the progress of the new HCRH trail in the Warren Creek area. He was making his way to the Defiance Trail, and when he saw me taking photos, shouted angrily “Love what they’ve done with the place!”

I’ve heard this reaction to the State Trail from many hikers over the years, as avid hikers are often aghast at what they see as more of a “road” than trail. The scope of construction impacts on the natural landscape of the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area (CRGNSA) and the millions in public funds being spent on the project rankles hikers who don’t see themselves actually using the trail.

Many hikers are also mystified as to how this project can received tens of million in funding while other, heavily overused Gorge trails are falling apart for lack of adequate funding.

Extensive cut and fill necessary to maintain trail grade meant a wide construction swath

These reactions are understandable, if misguided. The restoration of the surviving HCRH and the future trail segments that will soon complete the original route from Troutdale to The Dalles is an epic effort of ambition and vision in an era when both are rare quantities.

When the route is completed, it will become a world-class cycling attraction, and it is already drawing visitors from around the world. Guided bicycle tours have become a thriving business in the Gorge because of ODOT’s commitment to bringing the HCRH State Trail vision to reality, and businesses in Gorge towns are already seeing the benefits.

Other projects to promote the trail are also in the works. ODOT’s Gorge Hubs project is a new partnership with six cities in the Gorge to provide traveler information for trail users and boost the local economy. The Friends of the Gorge have launched the Gorge Towns to Trails project, a complementary effort to the HCRH State Trail to connect Gorge communities to public lands via trails.

Tourism in the Gorge is as old as the historic highway, itself. This is the Lindsey Creek Inn that once stood where the newly completed HCRH State Trail approaches Lindsey Creek

Plenty of local visitors will continue to use the HCRH State Trail as the project nears completion over the next few years, but the real benefit for Gorge communities is from visitors coming from outside the region. Unlike local visitors, tourists coming from elsewhere will book hotel rooms, purchase meals and take home locally-made products and art from the Gorge to memorialize their trip. These visitors make a much larger contribution to the Gorge economy than a local visitor who might stop by a brewpub on the way back from a day trip.

Gorge sunset from near Starvation Creek along the newly completed HCRH State Trail

A 2011 National Park Service study of tourism dollars shows outside visitors spending anywhere from 7 to 12 times the amount that local visitors spend on a visit to a given park, bringing hundreds of millions to local economies at many parks. There’s no reason why the Gorge can’t better manage the our already heavy demand from local visitors to the Gorge to allow for more outside visitors drawn by the HCRH State Trail to spend their dollars here.

The bigger picture is that anyone opposed to seeing casinos or bottled water plants in the Gorge should be part of supporting a tourism economy that builds on the scenery. Yes, tourism impacts must be managed to protect the Gorge for future generations, but the health of the Gorge economy is the essential ingredient to providing these protections over the long term.

The HCRH State Trail is part of that formula, and it deserves enthusiastic support from anyone who loves the Gorge. If you own a bicycle (or pair of walking shoes), give it a try — and then recommend it as an exciting new vacation destination to distant friends and family!