Author’s note: I started this article two year ago, and set it aside because of the conflicting emotions I had from the experience described here. I’ve thought a lot about how I reacted since then. Over the past few weeks, as I watched the Riverside Fire sweep through the Molalla River canyon, memories of the event in 2018 flowed back, once again. Hopefully, a couple of years of reflection will make this a more thoughtful retelling of the story.

_______________

We live in a cruel time. Politics of fear, rage and blind ideology are stoked by countless streams of media in the endless 24-hour cycles of “news” that has little to do with our everyday lives. All of this is relentlessly boiled up daily and served as a toxic brew that feeds directly into our country’s social unrest. But the constant drumbeat is designed to make us think otherwise, of course, and to entice us tune in for another day of advertising wrapped in more fear and loathing. It’s exhausting, overwhelming and discouraging, no matter your political outlook.

So, what’s the connection to this blog? It’s in the cure. In the Pacific Northwest, we are gifted with an escape hatch from this media overload with the greatest concentration and diversity of public lands in the world. These public spaces provide us with a blissful retreat from the daily onslaught coming from cable news, talk radio and social media.

Like most, my time in the woods is almost always spent decompressing from these social stressors, and the everyday pressures of life. That’s why I spent several weekends in the spring of 2018 in the Molalla River corridor, an area that I hadn’t really explored before. It’s a strip of Bureau of Land Management (BLM) land that was assembled through land swaps with private timber companies in the 1990s, and is now fully dedicated to recreation and forest restoration.

Most who visit the corridor are there to fish, explore the many mountain bike trails, swim in the crystal-clear Molalla River or simply enjoy the scenic drive. I went there in the off-season to take to beautiful rainforest scenery as spring foliage was just beginning to emerge. Much of the forest in the Molalla River corridor is recovering from century-old logging. The rebound is breathtaking and inspiring, despite the heavy logging that continues in the upper slopes of the watershed on land still owned by the timber companies.

We don’t yet know how the Riverside Fire changed the landscape in the Molalla River canyon when it swept through last month, but there’s a good chance that this riparian corridor experienced a mosaic burn, where patches of surviving forest remain among more severely burned forests. I’ll report back on that once we the smoke has cleared and we can better understand the full impact of the fire on the forest.

A change in plans…

And so, I was heading back into the Molalla River corridor on that lonely, rainy Sunday morning in 2018 to photograph the forest scenery in a couple of favorite spots I had found on previous visits. Oddly, I had passed a BLM ranger parked at one of the closed picnic sites, which surprised me on an early spring weekend. Otherwise, I had the place to myself.

Then I came upon a man lying in the middle of the road.

At first, I thought he might be a cyclist who had been struck by a car. The corridor has miles of developed mountain bike trails, but there was no bicycle in sight, nor any vehicle. Had the man in the road been hit and left there? Was he even alive? My heart was pounding as I pulled up. Then, to my relief, the man began waving for help. Thankfully, he was alive! But a wave of fear swept over me as to what his injuries might be.

I jumped from my car and yelled to him, “Are you okay?”

“Yes, but I broke my leg”, he answered, lifting himself awkwardly onto one elbow.

The man looked to be in his mid-30s. His leg was badly broken, and worse, his head was bleeding steadily from just above his left eye. He was lying on wet pavement in blue jeans and a denim jacket, both completely soaked by the steady rain. I was now very concerned about the seriousness of his injuries and whether this man was going into shock.

I ran back to the car to get a fleece blanket to cover him and asked him his name.

With a heavy accent, he said “Daniel. Daniel Hernández” offering me his wallet and identification, as if I’d asked to see it.

Now, this was not the man’s real name. I’ve simply chosen a common Hispanic surname to reflect his ethnicity, as this is central to the story.

“I fell off the cliff and broke my leg” he said, pointing at the 70-foot escarpment directly above the road. Then, quietly repeating to himself, “Damn, that was stupid… I can’t be missing work for this…”.

Kneeling there in the rain beside him, I was struck that he felt I needed to see his identification as he lay there, badly injured. As if he had to justify his presence to me, a bystander and complete stranger.

I wrapped Daniel in the blanket, and told him I had no cell service in the canyon, but that I had seen a BLM ranger a couple miles back, and wanted to drive back to try to catch him. Daniel nodded and asked if I had water for him to drink. I found a plastic cup in the car and left him on the road shivering and sipping water. It felt terrible to leave him behind, but I didn’t dare move him, and the BLM ranger might still be there and have a field radio. I could only hope that Daniel wouldn’t go into shock while I went for help, or even be hit by a car.

As I started to pull away to find help, a blue minivan suddenly appeared from the opposite direction, driving very slowly — warily — down the canyon toward us. The lone, older man inside kept his window up as he approached us, and clearly did not intend to stop. This shocked and angered me, and I jumped back out and waved him down anyway, actually stepping in front of his vehicle. He rolled his window down a few inches, and I asked him to simply stay there to keep an eye on Daniel so that I could go for help.

The man in the blue minivan reluctantly nodded, never saying a word to me or even looking me directly in the eye. He rolled his window back up and full ahead, finally stopping his vehicle a fair distance down the road. This left Daniel lying unprotected on the pavement, 30 feet behind him. The old man was clearly fearful and didn’t want to get involved, which made me both angry and sad. I didn’t blame him for being afraid, and yet his cold indifference was infuriating. Yes, it was a scary situation, but also a very human one. Couldn’t he see that?

I jumped back in my car and raced back down the corridor to the spot where the BLM ranger had been parked, just over a mile from where Daniel lay. I felt a wave of relief to round the final corner and see the ranger loading up his truck. I pulled right up to him, startling him, I think, and told him what was unfolding just up the road. He was a young man in his 20s, but clearly knew what to do. He immediately jumped in his truck and followed me back up the road to the spot where I had left Daniel.

As we approached the spot, the old man in the blue minivan quickly pulled away before we had even reached Daniel, without a word or gesture, even when I waved to him. He didn’t roll down his window or even make eye contact as he drove away. This mostly made me sad. I felt sorry for the old man, now.

The incident now took another scary turn as the BLM ranger struggled to get a 911 call out on his radio. This is apparently an ongoing problem for law enforcement and rescue within the walls of the Molalla River Canyon. He spent an agonizing 20 minutes before he finally got through, and the rain continued to fall.

While the BLM ranger worked his radio, I knelt down by Daniel to ask how he was doing.

“Okay” he replied.

“So, what were you doing up there?” I asked, immediately realizing that I sounded more suspicious than curious.

“I just needed to get out here for some peace and quiet, man. I was exploring that trail and tried to get a look at the river, and the ground just gave way”, he said, pointing to a spot at the top of the cliff where you could see the path of his fall through broken brush and ferns.

“Where’s your car?” I asked.

“Down the road, it’s a white van where the trail starts”, he said.

At this point, the BLM ranger had made radio contact, and called out that an ambulance from nearby Molalla was on the way. He then walked over to us, and stood several feet from where Daniel lay, asking him a similar series of questions, though through the lens of law enforcement. That’s one of the roles a ranger plays on our public lands, and he had clearly seen more than his share of unlawful activity in the corridor. But it was also true that Daniel was presumed suspect, even as he lay badly injured on the road.

In that moment, another wave of unexpected fear passed through me. Had I been naïve in trying to help Daniel? Had I put myself in real danger by stopping to help him?

Daniel offered the ranger his wallet, just as he had offered it to me. The ranger took it, looked at Daniel’s identification, then handed it back. Daniel had been laying there for at least an hour at that point, and was shaking. He asked if one of us had a cigarette. The ranger frowned and said “sorry”. I told Daniel I didn’t have a cigarette, either.

I kneeled there, talking with Daniel for the next 20 minutes as we waited for the ambulance. He was staying with friends near Molalla, and visited the corridor frequently to “get away”. That’s why I was there, too, after all. Yet, the ranger’s suspicion had me wondering about Daniel’s story, now. Daniel continued to quietly lament and blame himself for his fall, wondering how he would manage paying medical bills and the work missed from his injuries. He was genuinely distraught, and as he spoke, the fear and distrust about who he was that had crept into my own mind began to melt away, once again. He was just like me, right?

As we sat there in the rain, me next to Daniel and the ranger back in his truck monitoring the radio, it hit to me that Daniel wasn’t just like me at all. He had none of the security that I so take for granted in life — financial, social and even basic equipment for being in the outdoor. His life was completely different than mine, though we had both come to the forest that day to fulfill the same basic need to recharge and find some peace. Despite our very different worlds, we both needed to step away from life’s troubles and reconnect with nature. It was yet another reminder of the cruel times and divided society we live in, creeping into the sacred public refuge of the Molalla River rainforest.

Finally, we heard both an ambulance and fire engine racing up the road, and I reached out to shake Daniel’s muddy hand to wish him well. Blood was streaked down the side of his soaked face from the wound on his forehead. He squeezed my hand hard, and I felt good about making a human connection with him — even as I secretly felt ashamed of the moments of fear and suspicion that had flashed through my mind since I first found Daniel lying on the road.

When the ambulance pulled up, another wave of relief swept over me. My worst fear had been for Daniel to go into shock, and though I have a fair amount of first aid training, the idea of actually having to treat someone with serious injuries and going in shock really scared me. The rescue workers took over, checking Daniel’s condition and preparing to load him into their ambulance. Once again, Daniel offered up his now soaked wallet and identification, without being asked, and I finally realized this was a familiar, regular ritual for him.

While the rescue team worked with Daniel, I stepped back to chat with the BLM ranger. He could have been me 30 years ago — blond, outdoorsy, just out of college and looking for a career in public lands. He talked about how lawlessness was an ongoing struggle in the corridor for his agency. Despite the popularity of the area, there is still a fair amount of illegal activity, and the BLM is woefully understaffed and unable to provide a consistent presence there.

It was hard to hear such a young, enthusiastic person sound so jaded about those realities, but such is the nature of the work. And yet, it was the fact that Daniel fit a certain profile to the ranger that was most sad to me. Had I been laying on the road, I’m quite sure the reaction would have been different. Because the ranger was just like me… and Daniel was not.

When Daniel had been loaded onto a gurney and moved into the ambulance, I waved at the departing contingent of emergency vehicles and the BLM ranger. Daniel was safe, now, though his troubles in his life brought on by the fall had surely only begun. I’ll never know. We just two strangers brought together for a couple unexpected hours.

After everyone had left, I started back up the Molalla River canyon for an afternoon of soaking up the rainforest beauty. But the incident had rattled me beyond the initial shock of finding a badly injured man in the middle of a road. I spent most of that day reflecting — and regretting — my own feelings and suspicions that had emerged that morning.

On the way out that evening, I was startled to see Daniel’s white van, parked exactly where he said it would be. It was a beat-up 1980s panel van with a temporary license taped inside the rear window. Once again, my suspicions and fears surged at the sight of the old van. It looked sketchy. But why should it have mattered? Nonetheless, it did, because that judgement was in my subconscious, too.

Then I remembered Daniel’s words: “Damn, that was stupid… I can’t be missing work for this…”. I thought about him, probably in a hospital ER at that moment, running up a tab and facing weeks without work. I thought him squeezing my hand. Did he have a family or friends to help him out? Who would come get his van?

We all like to think we’re above our fears and biases, but this was one of those moments when they reared up for me, unexpected and unwelcome. How little we know about ourselves until we are pushed outside our comfort zones, and how very jarring those hidden feelings can be when they emerge.

And so, I resumed stewing about these many conflicting emotions for the long, rainy drive home in the dark that night… and for the next couple years.

* * * * * * *

I shared this story with friends and family through social media the next day, and received all manner of unexpected praise that I certainly wasn’t looking for. This only made me feel more uncomfortable and ashamed of the mixed emotions I had felt. Yes, I had helped this man, but in the moment, I had also moved toward fear and suspicion at the slightest suggestion. These are details I had not shared in my retelling at the time, and wished I had. It felt hollow and disingenuous, and I wished I had kept the entire story to myself.

So, I tucked away my notes and thoughts about the incident, periodically picking it up over the past two years and trying to figure out why it had impacted me so. Then the video of the brutal killing of George Floyd by a white Minneapolis police officer swept across our already fraught social landscape last May. For so many Americans, it crystalized an urgency to finally confront the racial divides that continue to plague our society. It forced the question, “what can we do as individuals to finally end this?”

For me, the George Floyd murder took me back to Daniel Hernández. Yes, the situation was very different, but the same underlying current was there: an injured Hispanic man feeling obliged to hand over his documentation — his right to be there — to a white bystander, to a white law enforcement officer and to white emergency responders. Daniel knows he belongs to an underclass in our society, and he knew his fate that day depended on navigating the assumptions that white strangers make about him every day. That includes me, the BLM ranger, and rescue unit… and the suspicious old man in the blue minivan.

What can I do? Small steps…

Since that incident in 2018, I had been actively examining my own unconscious biases and looking for ways to be a better social advocate and ally for change, as I clearly have some unconscious biases that need to be worked through. This blog is about our public lands in WyEast Country, so I would like to share how I am putting those ideas to work when I’m out in the forest. They are very small steps, but the old trail analogy applies: a few small steps are how we begin any important journey in our lives.

For me, one overdue step was to simply get to know Hispanic culture, since this represents the largest and fastest growing minority population in Oregon (and across the country). I’m an Oregon native, and yet I knew embarrassingly little about this rapidly growing part of the Oregon family, much less the longer Hispanic history of the West that preceded white migration and settlement.

So, I decided to learn Spanish. This continues to be a choppy work in progress that has been both humbling and hopeful, but one that I remain committed to. This first step was suggested to me by a Hispanic co-worker who had immigrated to Oregon in the 1990s, and described how welcoming and inclusive it felt when an English speaker would greet her in Spanish, and even attempt a conversation, depending on their Spanish skills.

I was nervous about this idea at first, as it seemed presumptuous and perhaps even racist. Who am I to presume someone is Hispanic based on appearance or even overhearing them speak? But she was exactly right. I gave it a try, and the reaction has almost always the same: friendly and appreciative. Now, when I run into Spanish speakers on the trail, I greet them as I do everyone, but instead of “Hi”, it’s “¡Hola!” I don’t know for sure, but I suspect part of the surprise is hearing a greeting in Spanish from me, a decidedly old white guy who might not seem like a friendly face in today’s racially divisive culture. But this makes it even more rewarding for me!

Earlier this year, on a very busy Memorial Day at Silver Falls State Park, I passed dozens of hikers, including many Hispanic families. Sometimes there was a moment of surprise when I would greet them in Spanish — who is this old white dude greeting me in Spanish? But then faces would typically light up, especially from parents with young kids, and I would get an enthusiastic “¡Hola!” and “¿Cómo estás?” (“How are you?”). And I would reply “Muy bien” (“Very good”) … and then I’d have to switch to English and point out that my Spanish is pretty terrible, but I’m working on it! Even that admission usually brings broad smiles, which is doubly rewarding.

I wish I had figured this out a long time ago, but I’m thankful my Hispanic friend encouraged me take this small step. She as right, and it turns out to be much more important step than I’d imagined.

In our mind’s eye, we imagine that everyone else sees us as the enlightened human beings we aspire to be, exactly equal to everyone else. But I’m learning that being white brings along heavy baggage when it comes to meeting black and brown people on our public lands. We know this because of extensive research on the subject than runs across the spectrum of people of color. But if you are a white person wants to believe that you are welcoming and without bias, it can be hard to accept this truth.

So, if I want to be part of changing that legacy, it means owning the reality that my being white is a highly privileged status in our society, and rethinking how I interact with people of color when I’m out on the trail is how I can be part of changing that injustice.

Public lands are for everyone? Not quite…

By the year 2040, our country is expected to be “majority minority”, thanks to the large and diverse Millennial generation coming of age, and an even more diverse Zoomer generation, right behind them. Whites will still make up the largest racial category for decades to come, but we will become just another minority in the larger, increasingly diverse population. So, that means the racial tensions that stem from a white majority will resolve themselves over time… right?

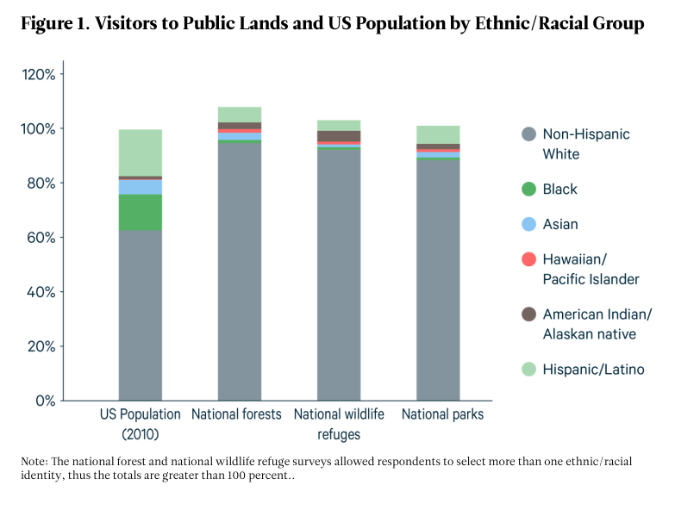

Possibly. But here’s the concerning news for the present: public lands continue to the be the overwhelming realm of white people, with a much less diverse cross-section of visitors compared to the overall population. The chart below from Resources for the Future shows the wide discrepancy:

Why is this? Partly culture and tradition, but research shows that most people of color fear hostility and open racism when visiting our public lands — including those who actively hike, camp and fish there, despite their apprehensions. Think about that: people of color seeking the same release from societal pressures that white people seek with time spent in nature are denied that because of the color of their skin.

This unjust reality is well documented in research and should be an urgent wake-up call. Research shows people of color reporting reactions of surprise and stares from white people they encounter on the trail, which carries an unmistakable (however unintended) message of “what are YOU doing out here? Many have outright racism, as well. This is real and it’s unacceptable.

I’d like to think that very few white people behave this way intentionally, but the good news is that remedy is very simple: be welcoming. A smile and a friendly “Hello!” is an easy enough start. If you’re hopelessly introverted, just a warm smile or wave will also do. Still friendlier options are “Beautiful day!” or “Isn’t it beautiful out here?”. These are easy greetings to offer, and I always leave every hiker I pass with “Have a great hike!”. This welcoming ethic should apply to every other activity on our public lands, of course.

Sometimes, you’ll get no response, but that happens when I greet other white people, too. Given the current reality for people of color on our public lands, I believe white people like me have an obligation to be part of the solution. It’s a pretty small step that anyone can take — and should.

I may not be able to stop racist taunts from happening (something far too many people of color report from their experiences on our public lands, sadly), but at least I can show that as white individual, I’m committed to a different, more egalitarian future. That’s also the connection to the broader movement happening in our country, too. We can all make a difference by learning and rethinking about our own actions in everyday life. Being welcoming is a small but important step we can all take, whether on a trail, or anywhere.

____________

“ e·gal·i·tar·i·an

adjective

1. relating to or believing in the principle that all people are equal and deserve equal rights and opportunities.

“a fairer, more egalitarian society”

noun

1. a person who advocates or supports egalitarian principles.

____________

There’s also a serious conservation concern that stems from the lack of diversity on our public lands, too. If our country will soon be majority minority, and people of color have not been welcomed on our public lands, then we’re headed for a time when only a few privileged white Americans will be truly invested in conserving our natural landscapes.

I’ve been a lifelong advocate for trails public lands because they’re an egalitarian gateway to nature. While we might argue about exactly how to manage our public lands, spending time out there ensures that we all value them as special, essential spaces in our lives. Resolving to become more welcoming to people of color on our public lands has special importance in this respect. Extending a greeting is not just a welcome, it’s also a validation that acknowledges another person’s right to be there, that we ALL own these lands and we are all responsible for passing them along to the next generation. When you think about it, that’s a profoundly unifying responsibility and common purpose that could go a long way in healing a fractured society.

* * * * * * *

And this takes me back to Daniel Hernández. I finally figured out that what bothered me most about that incident in the Molalla River corridor back in 2018. Where I felt a perfect right to be out in the forest that day, Daniel knew that he didn’t share that right. On paper, perhaps, but every white person he encountered that day also carried the implicit right — privilege — to judge his motives for being there, and therefore his basic right. And while I did want to help him, I was also part of that judging, even if for a few moments of doubt and fear.

As a white person, justifying my right to be somewhere is a burden I will never have to carry. But it’s also privilege I don’t have to exercise. That’s why I’m committed to changing my own interactions with brown and black people in whatever years I have left on this planet. For me, that starts with learning, listening and questioning my own behavior, and then accepting and welcoming all who are out there soaking of the forest, just like me.

Our public lands are a priceless gift from generations before us, and for so many, they are an essential refuge from life’s burdens. Now, the task is to ensure the survival of our public lands by ensuring that all Americans can experience the same joy, freedom and sense of peace they offer. It’s the egalitarian promise of our public lands. I believe we all have a responsibility to realize that promise, and the time is right now.

* * * * * * *

I know this article is long and a bit of a departure from what I usually write about on this blog, but if you’ve read this far, I appreciate you taking the time. It’s a tough subject to confront, and you may not even agree with my conclusions. But I’m always thankful for the opportunity to share my own experience with reflections with folks who share my love for WyEast Country!

Here are some resources on the topic that I found helpful, but there is much more out there on the subject that’s both informative and transformative:

“For People of Color, Hiking isn’t Always an Escape” – Reno Gazette Journal (2016)

__________________

Tom Kloster • October 2020

Raw and beautiful. Thanks for your words. I live in a county that is 40% Hispanic. And though everyone seems to get along, the divisions are stark. When the pandemic started, the orchard workers employed by my friend would sometimes get stopped by law enforcement to show that they were out on the roads because of the need to get to work. Me — the one with white skin and on his way to ride a mountain bike on public land — was never asked to explain my movements. I too look for ways to connect with the part of the county not white but these are isolating times and encounters are fleeting. But like your said, every small effort can matter.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Tom. Your thoughtful observations have sensitized more people than you probably know.

Thank you for sharing your thought processes. And the pictures gentled my nerves and spirit on this first rainy night in 94 days.

Your writings are so well done and thoughtful that I have read some of them over again.

Please keep up your excellent work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Tom, this had quite the impact on me. Thank you for sharing this, and for being who you are. Might I ask if there’s a typo here? “The lone, older man inside kept his window up as he approached us, and clearly did intend to stop. Was that supposed to be “clearly did NOT intend to stop”? I’ll be sharing this story with others. Thanks again for writing it. Best, Bernadette

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the kind comments, everyone — and for stopping by, as always! Bernadette, I ALWAYS appreciate corrections — thank you! 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks, Tom, for an excellent article.

–Linda

LikeLiked by 1 person

I appreciate you sharing this story Tom. And I hope more people begin to think like this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great story. Many of the fears we have are natural, we’re animals and wary of other animals. Exposure to other cultures and peoples releases that fear…and an absolute necessity for man to continue in some harmony with nature and the nature of mankind. I got to go see Mollala!! its right around the bend. Hope the fires of this year ravaging our standing brothers…the trees…will go out soon including the fires in mens hearts…. with a change in the political climate. RM

LikeLiked by 2 people

A very thought provoking article. . I think our fore-fathers understood that this country would be a melting pot of cultures and that it would be counter productive to force everyone to speak and write the same language. Recognizing diversity and making the effort to embrace it by learning and using another language to help others feel more comfortable is an admiral goal. The United Sates has never had an official language but that may soon change if the Republicans push through HR 997 which would make English the official language of the United States.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for the kind and thoughtful comments – Gracias! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Although this is quite a departure from your normal topic, it is important and needs to be said (and read by as many people as possible, especially Caucasians). Thank you for (a) helping Daniel in the first place; (b) investing the time and effort to write this; and (c) overcoming your doubts and conflicting emotions to share it with us!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Great Post! I really enjoy your blog and appreciate all the time and effort you put into it.

LikeLiked by 2 people

This is beautiful Tom. I would love to see it published more broadly (if it hasn’t been already). Perhaps High Country News? Outside Magazine? Locally in Columbia Community Connections? Your article is deserving of a large audience and will have more of an impact that way.

I speak a little Spanish too. I’ll be sure to use it more often thanks to your article.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hello

I very much appreciate your insightful article. Especially your resulting attempts to learn Spanish.

We live in a small community on the WA side of the Gorge with hispanic farm-workers of whom quite a few keep “in the shadows ” of our lives since there is much fear and prejudice.

We made friends with many of these neighbors and learned the language as well which resulted in us being invited to many gatherings and parties and opened up a whole new world and culture.

I hope more and more of us will go that route because I truly believe this is where the beauty and culture of this nation lies. We are made up of many cultures and should appreciate the opportunities to be found within that.

Thank you for your words.

Annette

LikeLiked by 2 people

A truly excellent, thought provoking article! Thank you, Tom!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Again, thanks for the comments — thought provoking and encouraging to read in our rather harsh election season! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the wonderful article. Our Subconscious biases do not define who we are as a person. It is your actions that matter. The fact that you fought your subconscious biases and did the right thing is something that should be celebrated! To often when people examine their subconscious biases they become depressed and fearful that if makes them a bad person. That leads them to bury those feelings and letting them fester. We need to acknowledge if we are to do anything about them. You are a wonderful human being who is trying to do what is right and just in the world and I thank you for that.

LikeLiked by 1 person