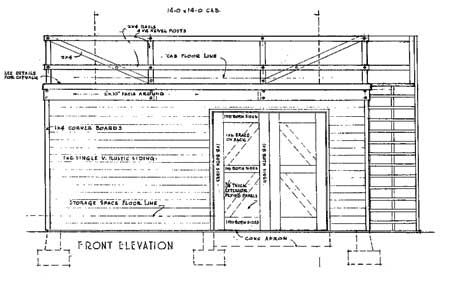

The McNeil Point Shelter.

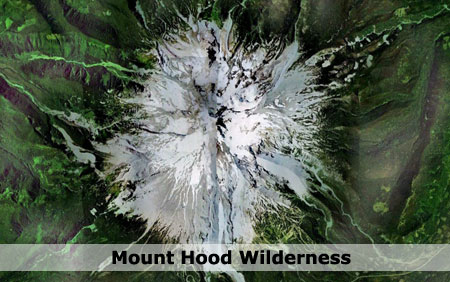

For decades, hikers and backpackers have taken Mount Hood’s famous Timberline Trail for granted — and why not? It was one of the earliest alpine hiking trails in the American West, and seems to have evolved with the mountain itself.

But the story of the trail is one of an original vision that has been realized in fits and starts, and the story is still unfolding.

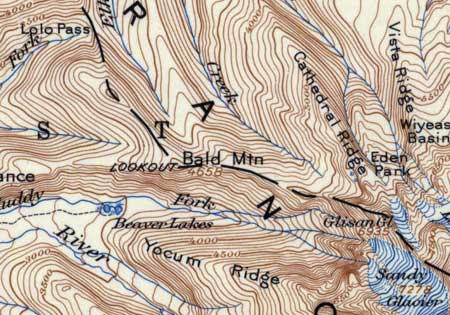

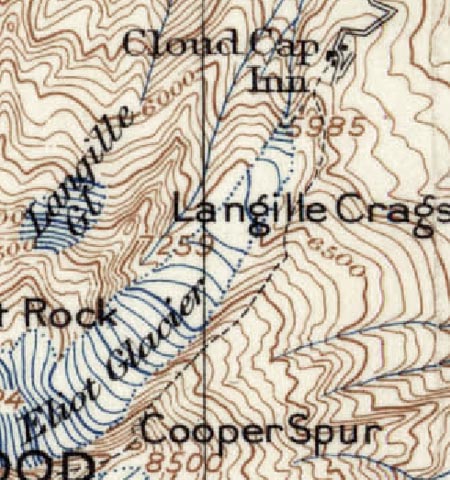

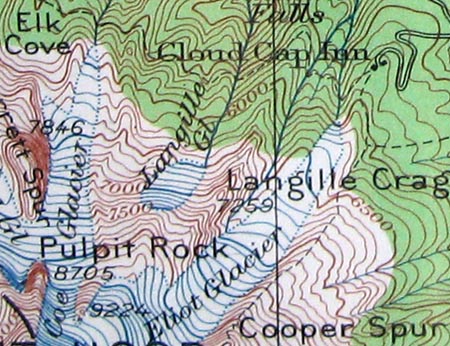

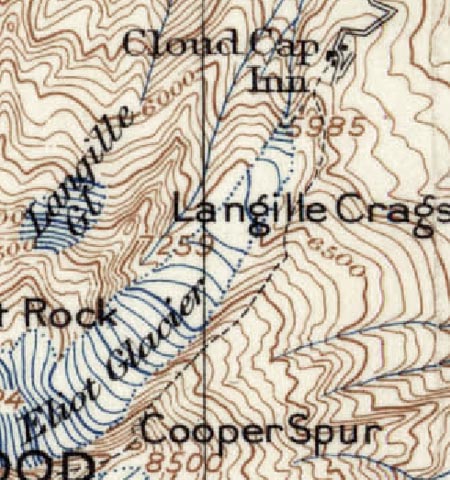

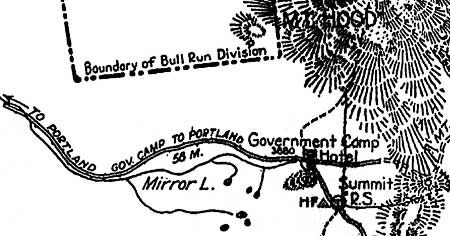

The first recreational trail on Mount Hood followed the South Eliot Moraine from Cloud Cap Inn to Cooper Spur, as shown on this 1911 map.

The first modern trail on Mount Hood was established in 1885, beginning at David Rose Cooper’s tent camp hotel, located near the present-day Cloud Cap Inn. The route followed the south Eliot Moraine to his namesake Cooper Spur. Soon thereafter, the Langille family would lead hikes and climbs on this route from the new Cloud Cap Inn, completed in 1889.

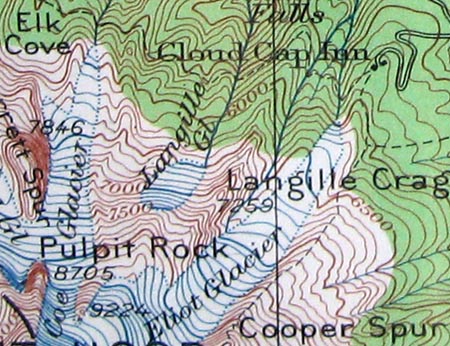

The Langilles also established a route from Cloud Cap to Elk Cove for their visitors, completing another section of what would someday become the Timberline Trail.

Hikers climbing toward Cooper Spur along one of the original sections of the Timberline Trail.

The route remains a popular trail, today, though it has never been formally adopted or maintained by the Forest Service. The first leg of this trail briefly functioned as a segment of the Timberline Trail, thanks to a temporary re-routing in the mid-2000s (more about that, later).

The significance of the original Cooper Spur trail is that it was built entirely for recreational purposes, the first such route on the mountain.

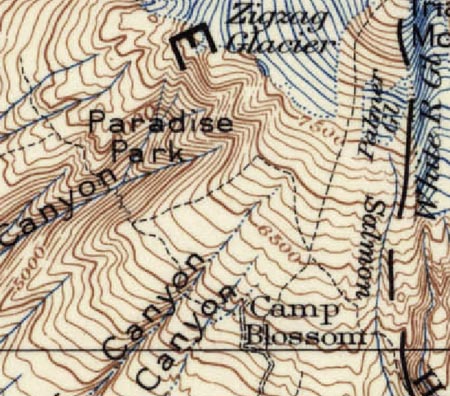

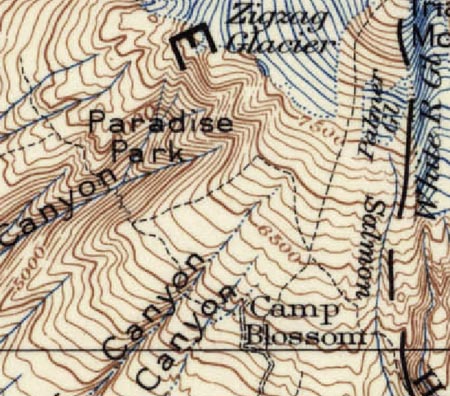

Camp Blossom was built some fifty years before Timberline Lodge was opened in 1938, but established the same network of trails that have since served the lodge.

Other hiking routes soon followed on the south side of the mountain, connecting the former Camp Blossom to nearby Paradise Park and the White River canyon. Camp Blossom was built by a “Judge Blossom” in 1888 to cater to tourists. The camp was at the end of a new wagon road from Government Camp, and located near present-day Timberline Lodge. It was eventually replaced by the Timberline Cabin (1916), and later, Timberline Lodge (1938).

The informal network of alpine trails radiating from Camp Blossom in the late 1800s still forms the framework of trails we use today. This is especially true for the nearly 7 miles of trail from White River to Paradise Park, which largely defined the Timberline Trail alignment in this section.

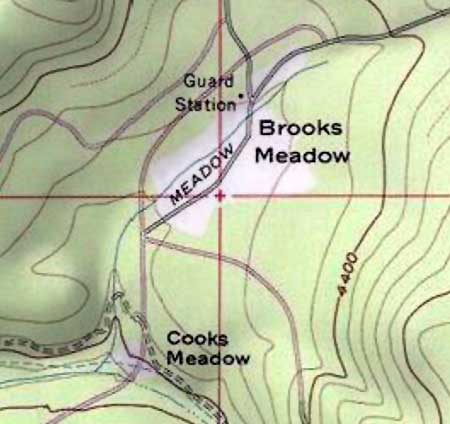

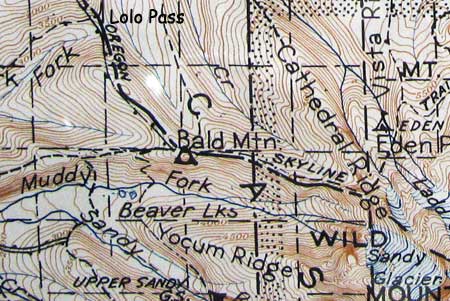

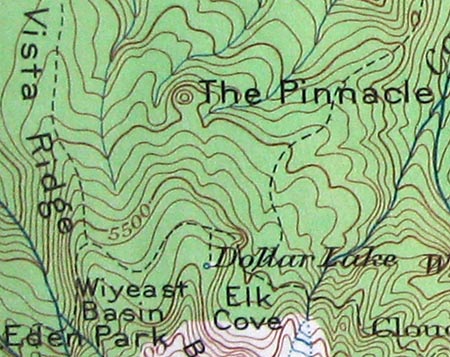

By the 1920s, the Langille family had developed trails from their Cloud Cap Inn to nearby Elk Cove (1924 USGS map).

By the 1920s, the Mazamas and other local outdoor clubs were pushing for more recreation facilities around the mountain, and public interest in a round-the-mountain trail was growing.

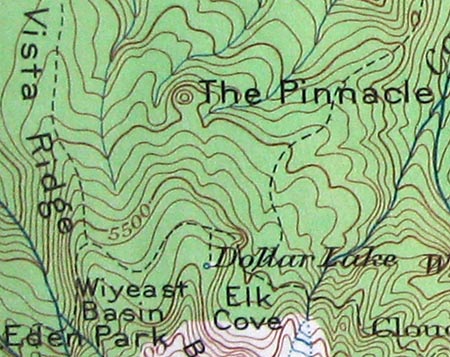

By this time, new Forest Service trails had been built on the north side of the mountain from the Clear Branch valley to Elk Cove and along Vista Ridge to WyEast Basin. These trails were connected at timberline (with a spur to Dollar Lake), creating another segment of what was to become the Timberline Trail. Combined with the route from Cloud Cap to Elk Cove, nearly 8 miles of the future Timberline Trail had been built on the north side of the mountain by the 1920s.

By the 1920s, the Vista Ridge and Elk Cove trails were established, extending the emerging Timberline Trail from Cloud Cap to Eden Park (1924 USGS map).

The Timberline Trail is Born

The concept of a complete loop around the mountain finally came together in the 1930s, during the depths of the Great Depression, when Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal recovery program, and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), brought the needed manpower and financial resources to the project.

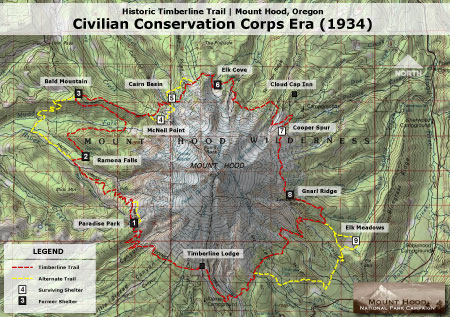

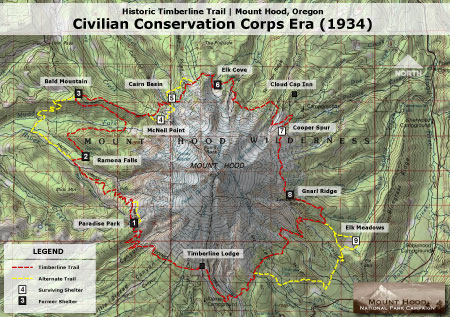

The CCC completed the new 37.6 mile Timberline Trail in 1934, stitching together the existing north side and south side trails, and covering completely new terrain on the remote west and east sides of the mountain.

The venerable Cooper Spur shelter still stands on the slopes above Cloud Cap, maintained by volunteers.

The Corps built a generous tread for the time in anticipation of heavy recreation use. The new trail was built 4 feet wide in forested areas, 2 feet wide in open terrain, and gently graded for easy hiking.

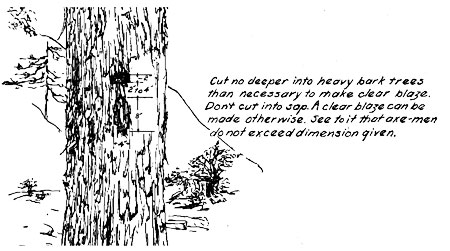

The trail was marked by square cedar posts placed at rectangular intervals over open country and by blazes in forested areas. Many of the distinctive trail posts survive between Cloud Cap and Gnarl Ridge, mounted in huge cairns.

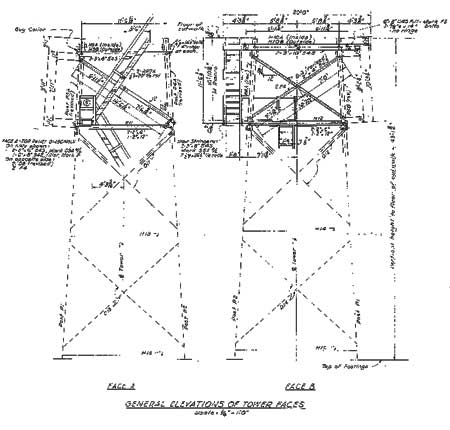

Shelters were built along the trail by the CCC crews as a place for hikers to camp and rest, and as protection against sudden storms. Most are of the same stone design, with a small fireplace and chimney. They were built with steel rafters instead of wood so that the structures, themselves, would not be used as firewood in the treeless high country, and also to withstand heavy winter snows. Of the six original stone structures, only those at McNeil Point, Cairn Basin and Cooper Spur survive (see large version of map, below).

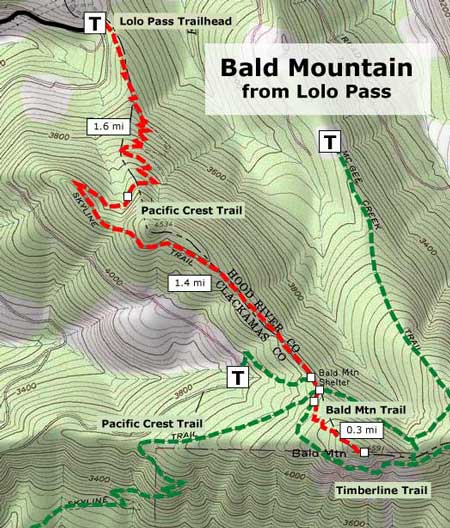

Map of the completed Timberline Trail and CCC era shelters.

(Click here for a large map)

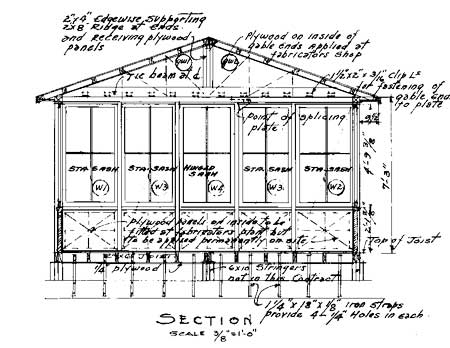

Three wood structures were also built along lower sections of trail, at Ramona Falls, Bald Mountain and Elk Meadows. Of the three, only the rapidly deteriorating structure at Elk Meadows survives.

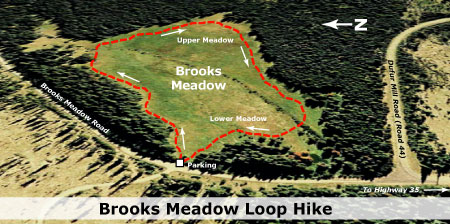

The completed trail featured a couple of oddities: the McNeil Point shelter had been constructed on a high bluff above the Muddy Fork that was eventually left off the final trail alignment, due to concerns about maintaining the trail at this elevation. Today, thousands of hikers nevertheless use the partially completed trail each year to reach the historic shelter and spectacular viewpoint.

Curiously, the shelter at Elk Meadows was also built off the main loop, perhaps because at the time, the meadows were seen as much a place to graze packhorses as for their scenic value. Like McNeil Point, this “forgotten” shelter continues to be a very popular stop for hikers, today.

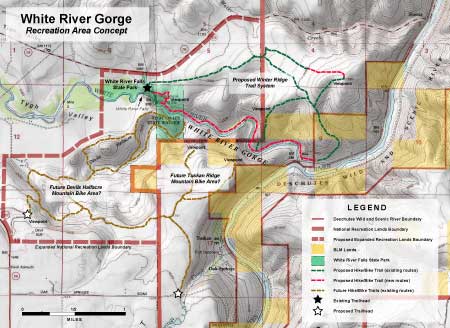

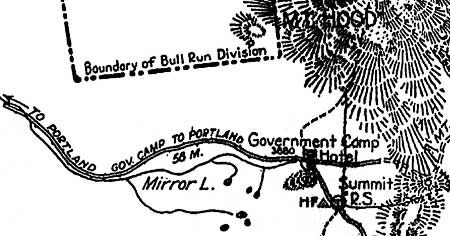

This 1921 map shows the Oregon Skyline Trail terminating at Mount Hood, before construction of the Timberline Trail. Note the early Bull Run Reserve encompassing the entire west side of the mountain.

By the late 1930s, much of the new Timberline Trail had also been designated as an extension of the Oregon Skyline Trail — according to maps from the time (above), the Skyline had previously terminated on the slopes of Mount Hood, above Government Camp.

The expanded Skyline Trail arrived at the Timberline Trail from the south, near Timberline Lodge, turned east and traced the new Timberline Trail counter-clockwise around the mountain before descending to Lolo Pass, then headed north to Lost Lake and the Columbia Gorge.

1970s Trail Renaissance

A third major era of trail construction on the mountain came in the 1960s and 1970s, when several major re-routes of the Timberline Trail were built.

By the early 1960s, the Oregon Skyline Trail had been relocated to the west side of the mountain, following the Timberline Trail from Timberline Lodge north to the Bald Mountain Shelter, then on to Lolo Pass.

By the time the Pacific Crest Trail was established in the 1968 National Trails Act, absorbing the old Skyline Trail, a new route across the Muddy Fork canyon was in the works for the Timberline Trail.

The Cairn Basin stone shelter is the best-preserved of the CCC-era structures, thanks to more protection from the elements than most of the original buildings.

By the early 1970s, this new section rounded Yocum Ridge from Ramona Falls, crossed both branches of the Muddy Fork, then ascended to the steep meadows of Bald Mountain, one of the most popular Timberline Trail destinations today.

The new Muddy Fork segment is now part of the Timberline Trail loop, with the Pacific Crest Trail following the old Timberline Trail/Oregon Skyline Trail alignment. Though less scenic, the old route is more direct and reliable for through hikers and horses.

In contrast, the scenic new route for the Timberline Trail has been a challenge for the Forest Service to keep open, with the Muddy Fork regularly changing channels, and avalanche chutes on the valley walls taking out sections of trail, as well.

Going, going… this view from the slowly collapsing Elk Meadows shelter will soon be a memory. This is the only remaining wood shelter of three that were built by the CCC.

In the 1970s, a section of trail descending the east wall of Zigzag Canyon was also relocated, presumably as part of meeting Pacific Crest Trail design standards. While the old route traversed open, loose slopes of sand and boulders, the new trail ducks below the tree line, descending through forest in gentle switchbacks to the Zigzag River crossing of today.

At Paradise Park, a “low route” was built below the main meadow complex, and the headwater cliffs of Rushing Water Creek. Like the Zigzag Canyon reroute, the Paradise Park bypass was presumably built to PCT standards, which among other requirements, are intended to accommodate horses.

The north side of the mountain also saw major changes in the early 1970s. The original Timberline Trail had descended from Cathedral Ridge to Eden Park, before climbing around Vista Ridge and up to WyEast Basin. The new route skips Eden Park, traveling through Cairn Basin, instead, and climbing high over the crest of Vista Ridge before dropping to WyEast Basin.

Beautiful meadow views line the “new” Vista Ridge trail section completed in the early 1970s.

Finally, a section of trail near Dollar Lake was moved upslope, shortening the hike to the lake by a few hundred yards, and creating the sweeping views to the north that hikers now enjoy from open talus slopes east of Dollar Lake. Just beyond Dollar Lake junction, the descent into Elk Cove was also rebuilt, with today’s long, single switchback replacing a total of six on the old trail which descended more sharply into the cove.

In each case, the new trail segments from the early 1970s are notable for their well-graded design and longer, gentler switchbacks. While the main intent of the trail designers was an improved Timberline Trail, the new segments also created a numerous new routes for day hikers who could follow new and old trail segments to form hiking loops. These loops are among the most popular hikes on the mountain today.

The Future?

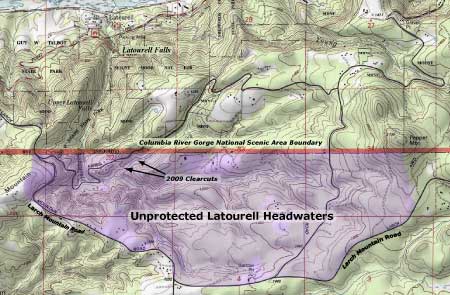

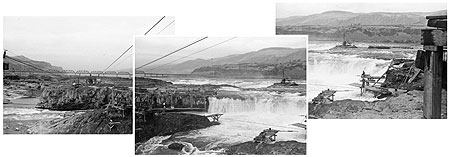

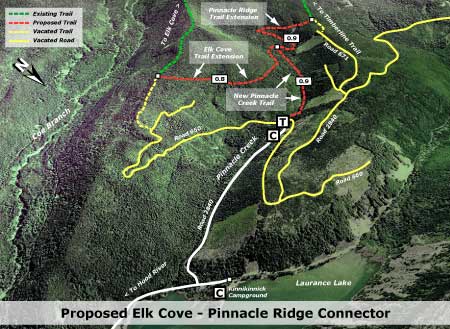

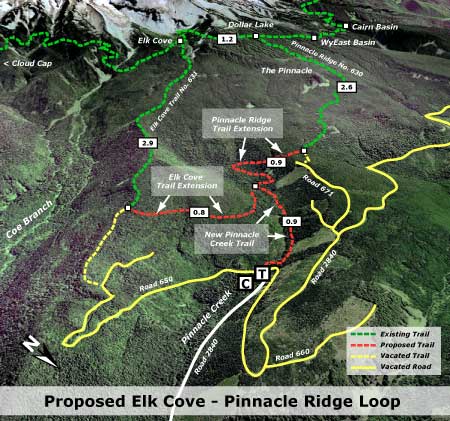

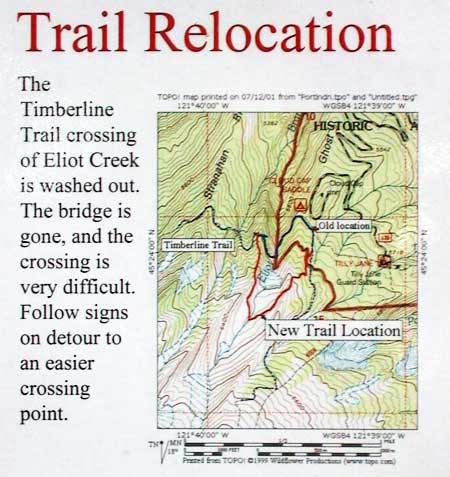

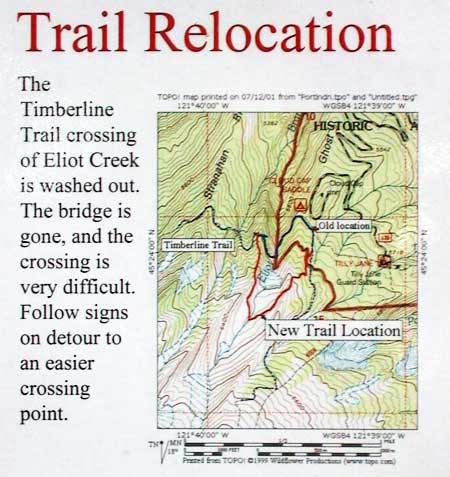

The retreat of Mount Hood’s glaciers in recent years has destabilized the outwash canyons, and in the past two decades, massive debris flows have buried highways and scoured out streambeds. One of the oldest segments of the Timberline Trail, near Cloud Cap, has been disrupted by washouts for nearly a decade, and is now completely closed, thanks to a huge washout on the Eliot Branch in 2007.

Sign from the first re-route, posted in 2001. Now the trail is completely closed at the Eliot Branch.

The Forest Service has since struggled to find funding to reconnect the trail at the Eliot Branch. The first washout moved the stream crossing uphill, taking advantage of the original Cooper Spur path established in the 1880s, then crossing to a parallel climbers path on the north moraine of the Eliot Glacier.

This temporary crossing lasted a for a few years in the early 2000s before the massive washout in 2007 permanently erased this section of trail. This portion of the loop as since been completely closed, though hundreds of hikers each summer continue to cross this extremely unstable, very dangerous terrain.

Site of the Eliot Branch washout and closure -- and the risky route hikers are taking, anyway.

The growing volatility of the glacial streams will ultimately claim other sections of trail, creating an ongoing challenge for the Forest Service to keep the Timberline Trail open each summer.

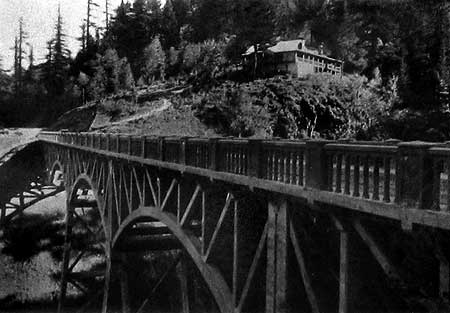

If repairing the washouts along the trail were as costly as those along the nearby Mount Hood Loop Highway, then there might be some question of whether it makes sense to keep the trail open. After all, millions of dollars are being spent this year to rebuild the Mount Hood Highway bridge over White River, yet again, in an area that has had repeated washouts.

Hikers crossing the Eliot Branch before the 2007 washout.

By comparison, a wilderness trail is exceptionally cheap to build, and much less constrained by topographical or environmental concerns than a road. It really just comes down to money and priorities, and the Forest Service simply doesn’t have the funding to keep pace with the growing needs of the Timberline Trail. With even a modest increase in funding, the trail can be rebuilt and adapted to periodic washouts, or other natural disturbances.

Speaking Up

One way to have an impact on the funding situation for the Timberline Trail is to weigh in with your Congressman and Senators. While the current political climate says that earmarks are dead, history tells us otherwise: ask for an earmark for the Timberline Trail. After all, the trail is historic and an international draw that brings tourists from around the world to help boost local economies.

If you’re not an earmark fan, then you can argue for an across-the-board funding boost for forest trails as a job-producing priority in the federal budget. A ten-fold increase over current levels would be lost in rounding areas in the context of the massive federal budget.

Yet another angle are the health benefits that trails provide, particularly given the federal government’s newly expanded interest in public health. This is emerging as the best reason to begin investing in trails, once again.

Hikers negotiating the Muddy Fork crossing after the 2002 debris flow swept through the canyon.

Of particular interest is the fact that Oregon Congressmen Earl Blumenauer and Greg Walden actually hiked the loop, just before the 2007 Eliot Branch washout. One is a Democrat, the other Republican, so you can cover your bipartisan bases with an e-mail both! They share the mountain, with the congressional district boundary running right down the middle, so both have an interest in the Timberline Trail.

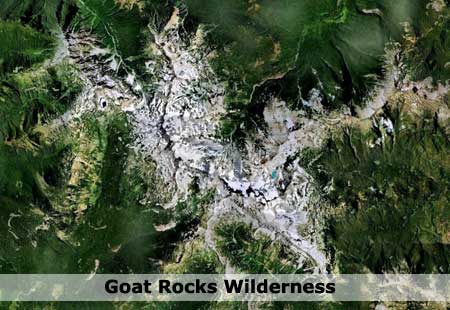

Finally, Oregon Senator Ron Wyden championed expanded wilderness for the Mount Hood area for years, and President Obama finally signed the bill into law earlier this year. So, another angle is to argue for the needed funding to support trail maintenance in these new wilderness areas, especially since they will require more costly, manual maintenance now.

It really makes a difference to weigh in, plus it feels good to advocate for trails with your Congressional delegation. Here’s a handy resource page for contacting these representatives, and the rest of the Oregon delegation:

Here’s how to send an e-mail to Congress

Thanks in advance for making your voice heard!