The Burdoin Fire was already moving east toward Coyote Wall on July 18, 2025, just hours after it started (photo: KVAL)

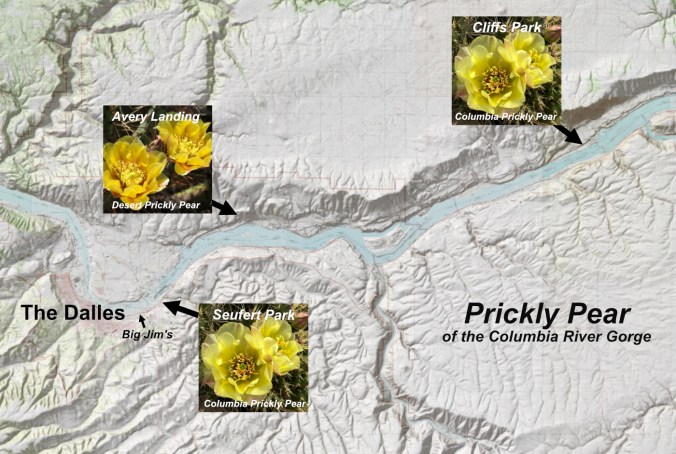

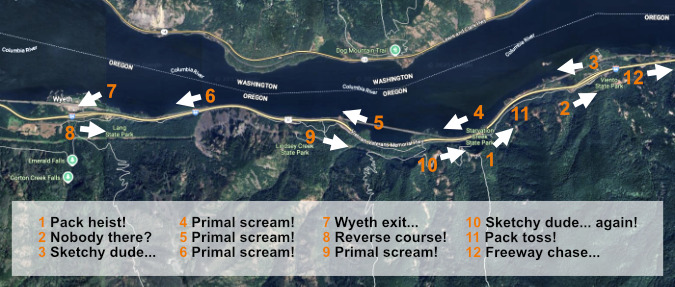

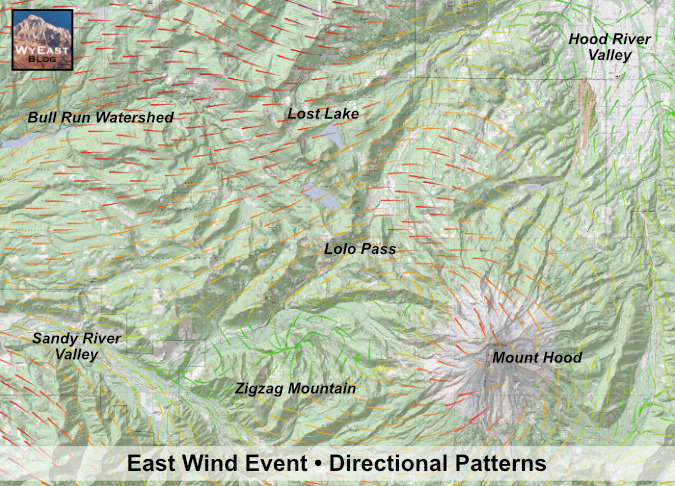

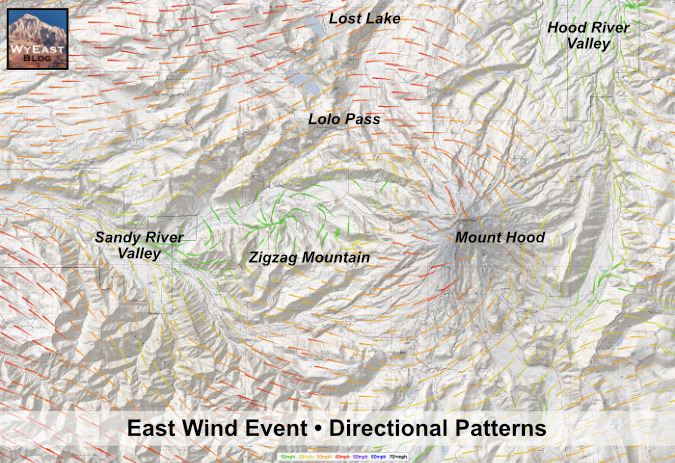

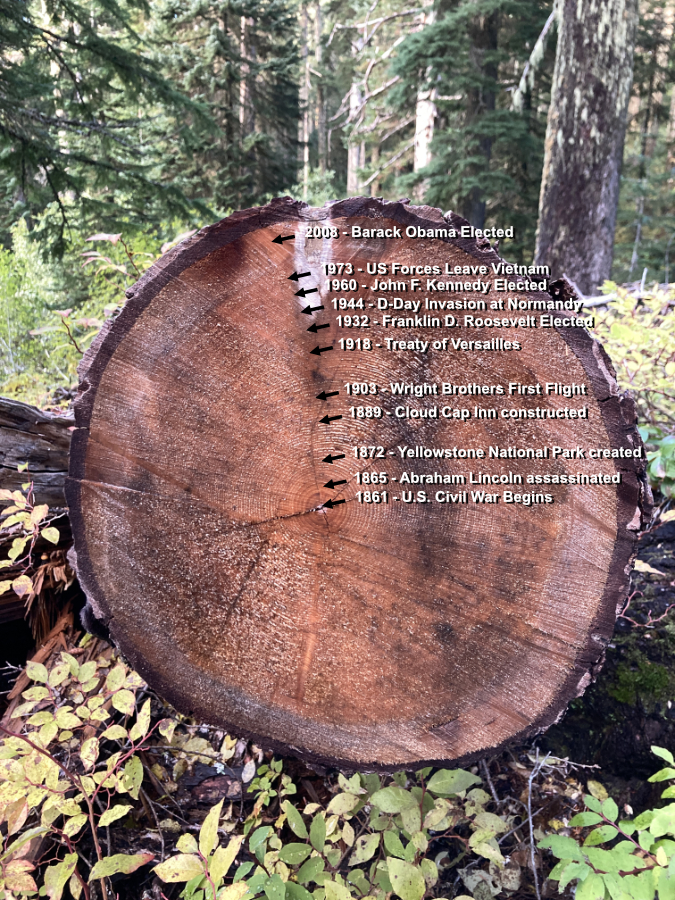

The Burdoin Fire erupted along the shoulder of Washington State Route 14 on a warm Friday afternoon last July, about two miles east of the town of White Salmon. Like most wildfires in the Gorge, it was human-caused and could have been prevented. Fanned by summer winds, the fire quickly spread eastward, sweeping across some of the best-known, most treasured public lands in the Columbia River Gorge, burning through iconic places like Coyote Wall and Catherine Creek.

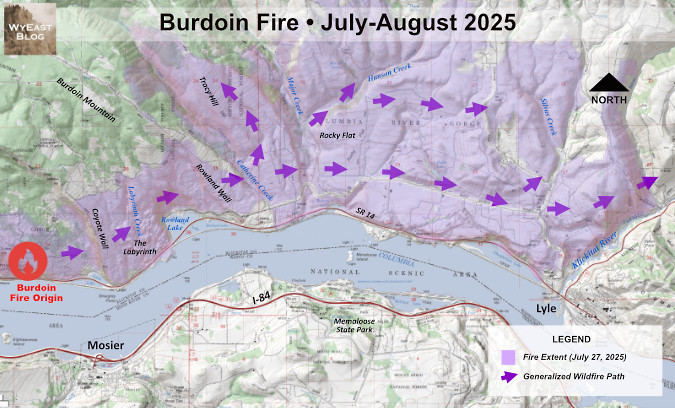

On just the second day, the fire had roared into the Catherine Creek area and was now threatening the town of Lyle, a full seven miles upriver from its origin. That day, the Klickitat County Sheriff issued a Level 3 “Go now!” order and the town and surrounding area were evacuated. More than 900 wildland firefighters would eventually be on the ground over the next two weeks to help contain the blaze. The map below shows the general path of the fire over the days that followed.

[click here for a large version of the map]

By the time it was controlled in mid-August, the fire had burned a swath nearly 10 miles long and blackened more than 11,000 acres. Though the town of Lyle was spared, more than 100 structures were lost in the fire. No lives were reported lost in the event. The full scope of the impact on the Oak Savannah ecosystem remains unknown until spring, when it will become clear how the Oregon white oak trees fared. This 3-part series of articles is a snapshot in time as of early December, when the ecosystem recovery had visibly begun, but with many questions about long-term resiliency unanswered.

What’s dead and what’s alive?

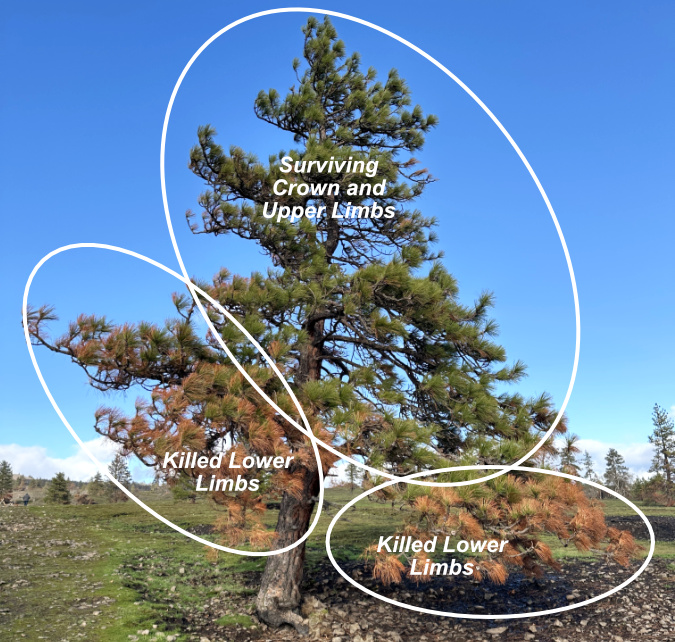

With Ponderosa pine it’s easy to see where fire has killed limbs or whole trees simply by where green foliage remains a few months after a fire. Sometime conifers can produce new growth from limbs whose needles were browned or even burned off by fire, but usually they sacrifice these limbs and focus their energy on green, healthier limbs.

The impact of fire on conifers is almost immediate, with burned areas turning brown (or with foliage completely burned away) and surviving areas retaining their green, living foliage.

There’s a benefit to sacrificing low-hanging limbs that is an evolutionary adaptation for fire-dependent conifers like Pondersosa pine, Western larch and Douglas fir. By shedding lower limbs over time, whether through exposure to fire or simply aging, they reduce the risk of these limbs providing a “ladder” for intense fires to climb into the crown of a tree, which it is much less likely to survive. Their fire-adapted thick bark, especially on older trees, helps protect the trunk against all but the hottest fires.

Over the longer term, conifers that lose more than half their foliage will often struggle to rebuild a canopy sufficient to survive, so in the years following a fire some heavily impacted Ponderosa pine in the Burdoin area may weaken and eventually lose the battle.

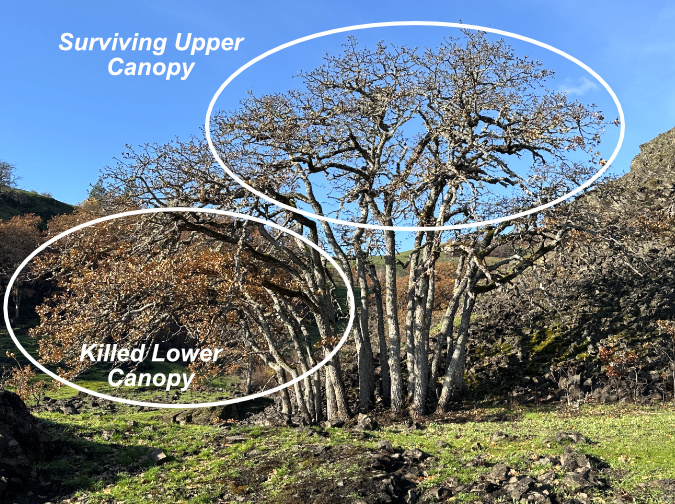

For deciduous trees in the dry East Gorge, like the dominant Oregon white oak and occasional Bigleaf maple, the visual impact of fire in the months after a burn can be counter-intuitive. With most fires occurring in the dry summer months, the immediate impact is browned leaves left hanging on scorched limbs, killed by the heat but not completely burned away. In fall, healthy leaves on surviving trees will turn color and drop naturally, following their annual cycle.

Understanding what survived on deciduous trees in the first winter after a fire is counter-intuitive, as the burned limbs and trees typically don’t drop their leaves in fall.

However, brown, killed leaves tend to hang on during the first winter, whether on just a burned limb or an entire tree killed in the fire, thus interrupting the normal process of dropping leaves in fall as they enter winter dormancy. Trees or limbs killed by fire are thus frozen in time, with brown, dead leaves hanging from killed limbs seeming to be the survivors, and healthy, bare limbs seeming to be killed by the fire. After the first winter the burned leaves will eventually drop off, and when new foliage emerges in spring the surviving trees will be more intuitive – green foliage on the survivors, with bare limbs and trees showing the true impact of the fire.

Learning from the Aftermath in Three Parts

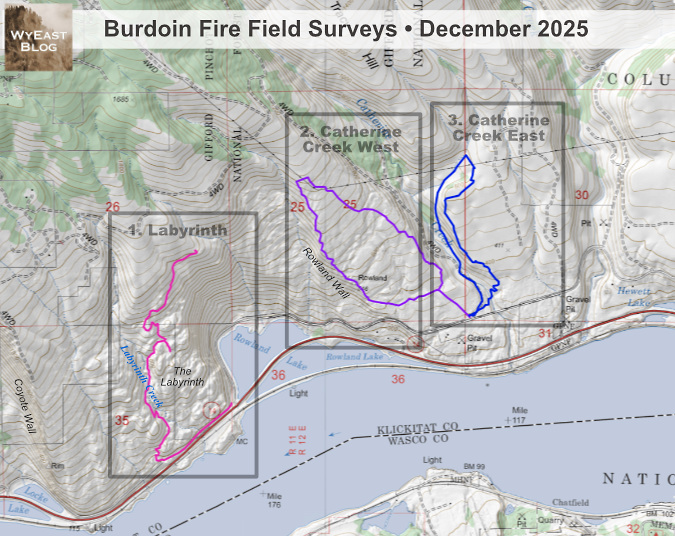

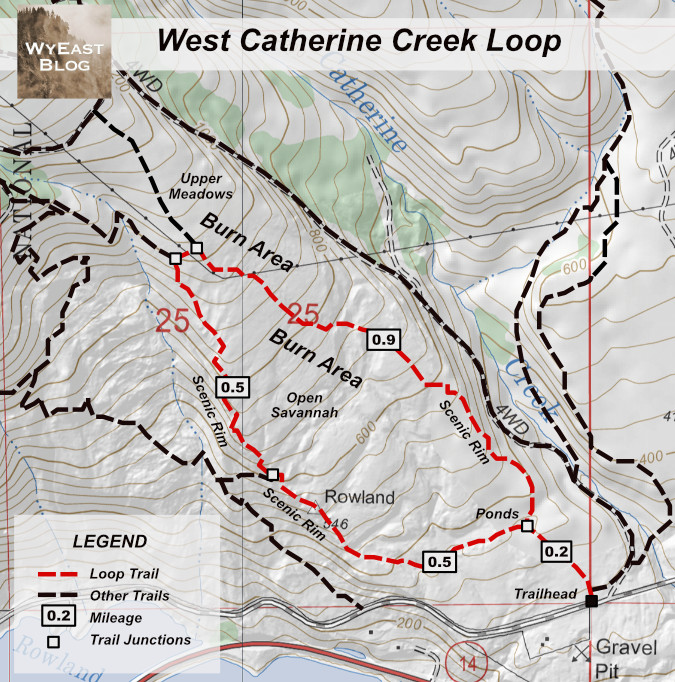

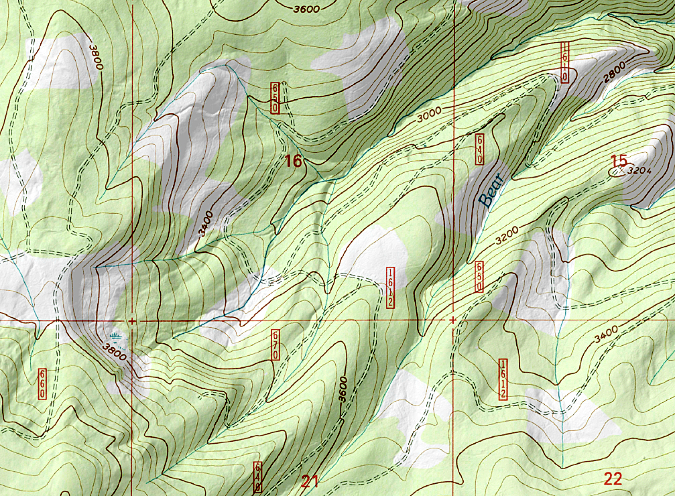

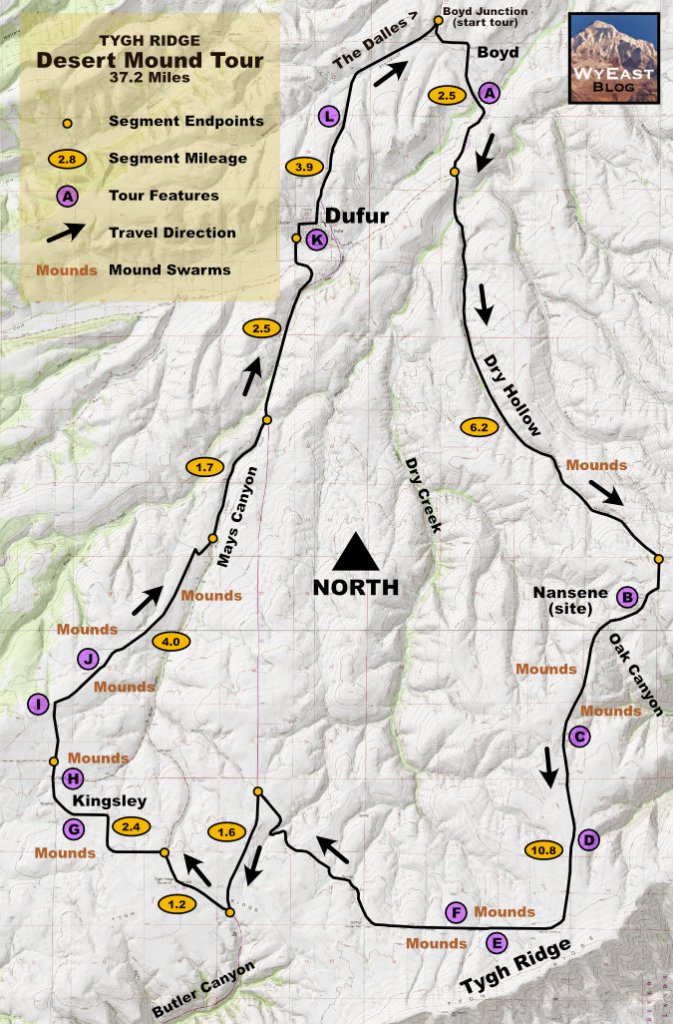

With any wildfire, there is much to learn in the immediate aftermath, and this is especially true in the oak savannah grasslands of the East Gorge, where a single season of regrowth can erase much of the visible burn scar left from a fire. This 3-part series is a virtual survey of the aftermath of the 2025 Burdoin Fire in three separate areas of the burn (shown on the map, below), each centered on a popular trail and each with a different story to tell.

[click here for a large version of the map]

This first installment examines the west end of the fire, nearest its origin, where it burned across the area known as the Labyrinth. The second installment will focus on open savannah country between the Rowland Wall and Catherine Creek, and an area that had already burned in the fall of 2024. The third installment will survey Catherine Creek canyon and the burned savannah areas to the east of the canyon. The trail routes followed for each survey are also shown on the above map. The photos for these tours were taken in December 2025.

The Labyrinth: A Story of Wildfire Resiliency and Renewal

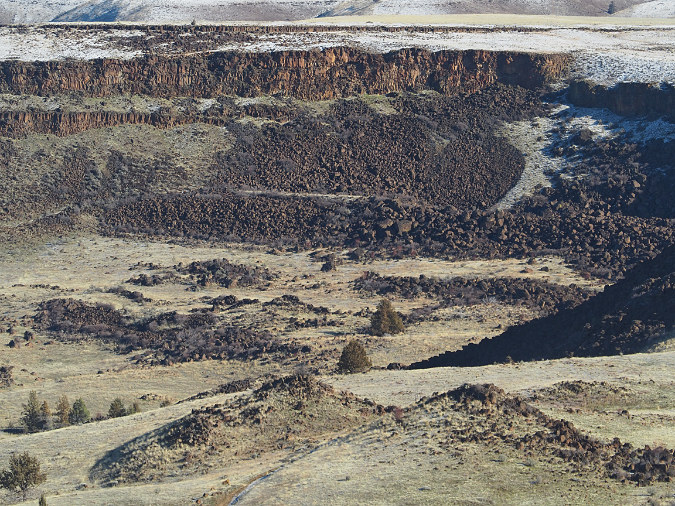

Few trails in the Gorge reveal the power of the ice age Missoula Floods that shaped the landscape like the Labyrinth Trail, which winds through a tortured landscape of basalt walls, fins and mesas stripped bare to bedrock by these massive floods just 13,000 years ago – a geologic blink of an eye.

The trail corkscrews steeply upward through this rocky maze until it suddenly reaches the gentle, wildflower-filled upper slopes. Here, above the high-water flood levels that rose to be as much 600 feet deep, soils were left intact. We’re only beginning to understand the scale of these floods, though scientists now believe there were at least 40, and perhaps as many as 100 of these catastrophic events over two millennia, shaping the rugged Gorge as we know it today.

The basalt mesa known to hikers as Accordion Rock rises above a burned landscape in the Labyrinth. Bright green grasses and meadow wildflowers had already begun to emerging by late November, just four months after the Burdoin Fire had burned through. The Oregon white oak trees in this view aren’t showing fall color; instead, these are leaves killed by the fire and left hanging long after healthy oaks have dropped their leave and entered winter dormancy. We won’t know the full impact of the fire on trees like these until spring.

Along its route, the Labyrinth trail passes through dense groves of mostly stunted Oregon white oak and scattered, often stunted Ponderosa pine growing in the thin soils that exist within the flood-scoured maze of the Labyrinth. Trees in this area were hit hard, in part because they live a stressed life in the already harsh conditions. By comparison, the deeper soils and gentler slopes above the Labyrinth support thriving groves of large oaks and impressively tall Ponderosas. Size and vigor matter for trees exposed to fire, and trees on these upper slopes seem to have fared somewhat better, at least at this early stage of recovery. We won’t really know until spring.

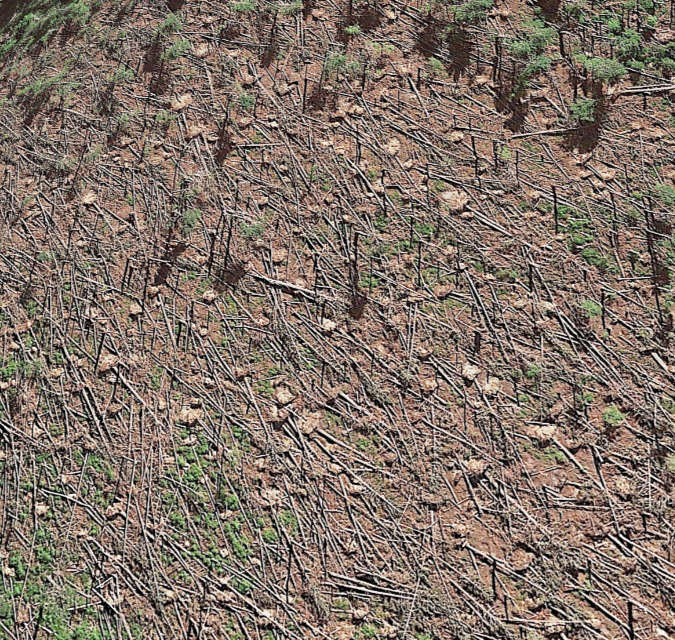

This was the first major fire to hit the Labyrinth in many years, another factor shaping how and where the burn impacted the landscape, as some of the most impacted areas are where a dense understory vulnerable to fire had formed over decades, often with accumulated debris in the form of fallen trees and limbs. This had a striking impact in fueling the flames in ways that can already be seen in just the few months since the fire, so there is already much to learn about fire resiliency and ecosystem renewal in the Labyrinth.

The Fallen Oaks

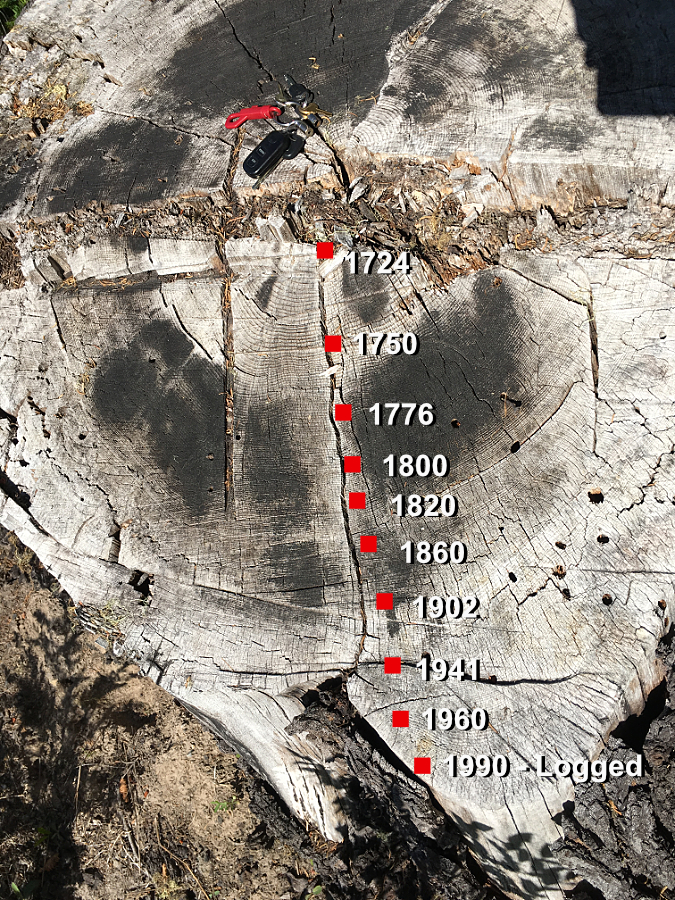

Together with Ponderosa pine, our native Oregon white oaks are a keystone species in the East Gorge, supporting hundreds of species of wildlife that rely upon them. One of the important benefits they bring are the signature cavities that form in older trees where they have been scarred or have simply shed limbs, providing critical shelter for wildlife.

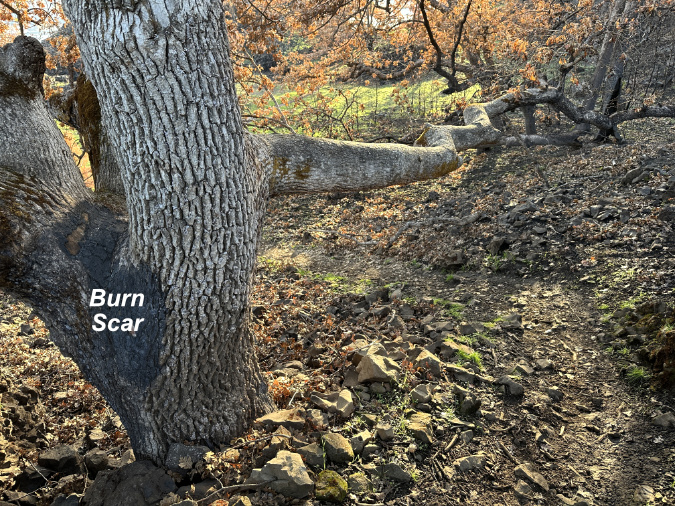

The fire aftermath along the Labyrinth Trail shows how fire can both create these cavities while also exploiting them to topple whole trees. By creating new scars, fires can expose heartwood that will eventually decay to become hollows. Yet, the same openings also allow fire to reach dry heartwood, ultimately felling entire trees by burning them from the inside out. There are many large oaks that met this fate throughout the Labyrinth

This big oak along the Labyrinth Trail was felled by the fire, yet it didn’t entirely burn. Instead, the fire burned from inside the tree’s hollow base. The unburned bark and browned leaves on its downed top suggest that it fell after the main fire event had move eastward, yet left the tree’s hollow core smoldering until it finally collapsed under its own weight.

This is the stump of the tree shown in the preview view (the top can be seen in the background) showing how the fire burned inside the tree long enough to completely hollow it, eventually causing the tree to collapse.

This big oak along the Labyrinth trail met a similar fate, with its charred, hollowed-out stump in the foreground and the tree’s collapsed, unburned trunk and limbs beyond.

This big oak was also toppled by fire burning within its hollow trunk. Part of the tree’s top is lying to the right, unburned because it likely fell after the fire had already swept through and consumed the understory brush and debris here. The blackened area in front of the tree tells the story of a main trunk that had enough deadwood inside to fuel a complete burn, leaving only a white line of ashes to mark where it fell.

This wide view of the previous fallen oak shows the line of ashes left from the completely burned main section of its trunk and a scattering of green, upper limbs left mostly unburned by the fire. Like the previous examples, the unburned bark on these limbs show that the tree fell sometime after the fire had already cleared the understory here and moved eastward.

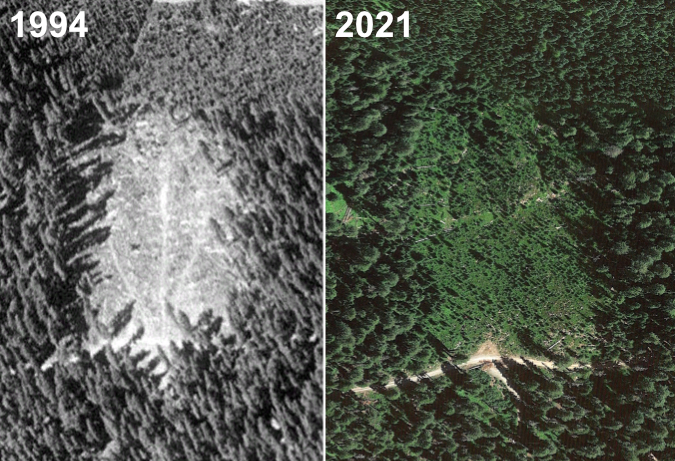

Oak Showing their Resilience

In the central Gorge, where the Eagle Creek Fire roared through in 2017, Bigleaf maple have emerged as a super-species in the forest recovery process. Throughout the lower elevations of the Gorge fire burn scar, thickets of new leaders exploded from the stumps of burned Bigleaf maple trees within a year. Today, many of these newly sprouted stems have grown to be 10-15 feet tall. Over time, 3-5 of these leads will become dominant. We know this from the mature, multi-trunked rainforest maples that are so familiar and iconic in the Gorge – only, now we can better understand one reason why this form is so common.

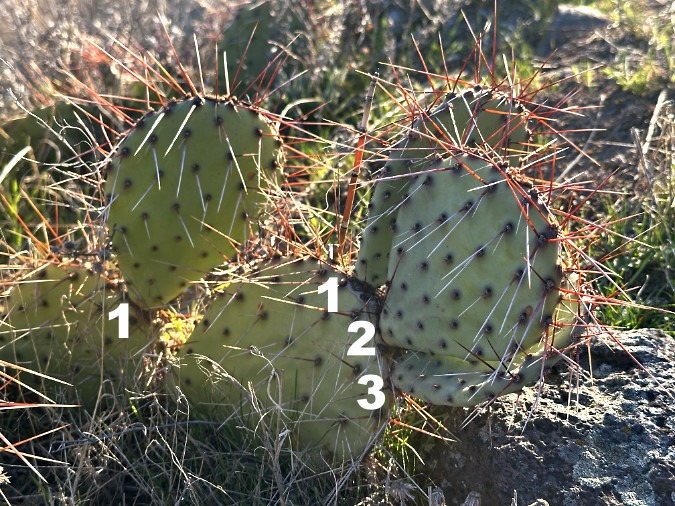

This survival strategy is much the same for Oregon white oak. While they lack the thick, protective bark of a Ponderosa pine to protect the living cambium layer beneath their bark, many oaks along the Labyrinth Trail are already cashing in their adaptive insurance policy by pushing up new shoots from their base. This, just months after the fire and long after the normal spring growing season, shows how completely adapted to – and reliant upon – wildfire our native oaks have become.

Like many of the Oregon white oak in the Labyrinth, this tree looks quite dead at first glance, still covered with killed foliage that should otherwise have been shed with the fall leaf drop. But a closer look….

…reveals this oak to have already pushed up new shoots from its intact roots.

Still more surprising, new growth was also emerging from the main trunk, where the tree’s bark was thickest and protected the tree just enough to lose its limbs to the fire, but not its main trunk.

This grove of oaks in the Labyrinth was cleared of most of its understory and accumulated debris by the fire. Many of the lower limbs have been killed by the fire, as revealed by the scorched leaves still hanging from the lower third of these trees. The upper limbs survived long enough to shed their leaves in the fall, leaving them bare for the winter and more likely to produce new foliage in the spring.

This close-up view of the previous image shows a rusty stripe within a larger bare patch extending from a burned-out stump – all are telltale signs that a tree that was downed in the fire (or perhaps already on the ground), and burned long and hot here. The lingering embers burned hot enough to turn brown, living soil into red, mineral soil, marking where the fallen tree trunk lay. The surrounding, darker soil marks the area where the fire had sufficient fuel to burn long enough to kill the roots and seeds of understory plants that are otherwise rebounding around this cleared patch.

It’s hard not to become attached to iconic trees, and this picturesque twin-trunked oak at the top of the Labyrinth is a sentimental favorite to many. Though the fire swept through here, this fine tree seems to have survived… though we won’t know for certain until spring foliage appears.

A closer look at the charred area to the right of this iconic oak shows how narrowly this tree dodged the fire – just a few inches that might have decided its fate.

In the upper meadows above the Labyrinth, the oaks are much larger, thanks to deep soils above the flood-scoured Labyrinth. However, the better soils here and an absence of fire in recent years also contributed to an overgrown understory and accumulation of debris that completely burned away in the fire. We’ll know in the spring if the heat from this intense burning was too much for these big groves to survive.

Bigleaf maple aren’t common in the East Gorge, though they thrive in niche locations along cliff walls and protected gullies that produce groundwater seeps and concentrate stormwater sufficient for them to live in this desert climate. This Bigleaf maple clearly lost its lower limbs to the fire – those still covered in scorched foliage – but its upper limbs lived to shed their foliage normally in the fall, suggesting the fire move fast and low here, allowing the main trunk and upper limbs to survive.

Another bigleaf maple in the Labyrinth that seems to have survived the fire, with the yellow leaves on the left making limbs that survived long enough to turn in the fall and scorched leaves on the right that were killed in the fire. Like the oaks, we’ll know in the spring whether these maples have survived the fire to grow for another season.

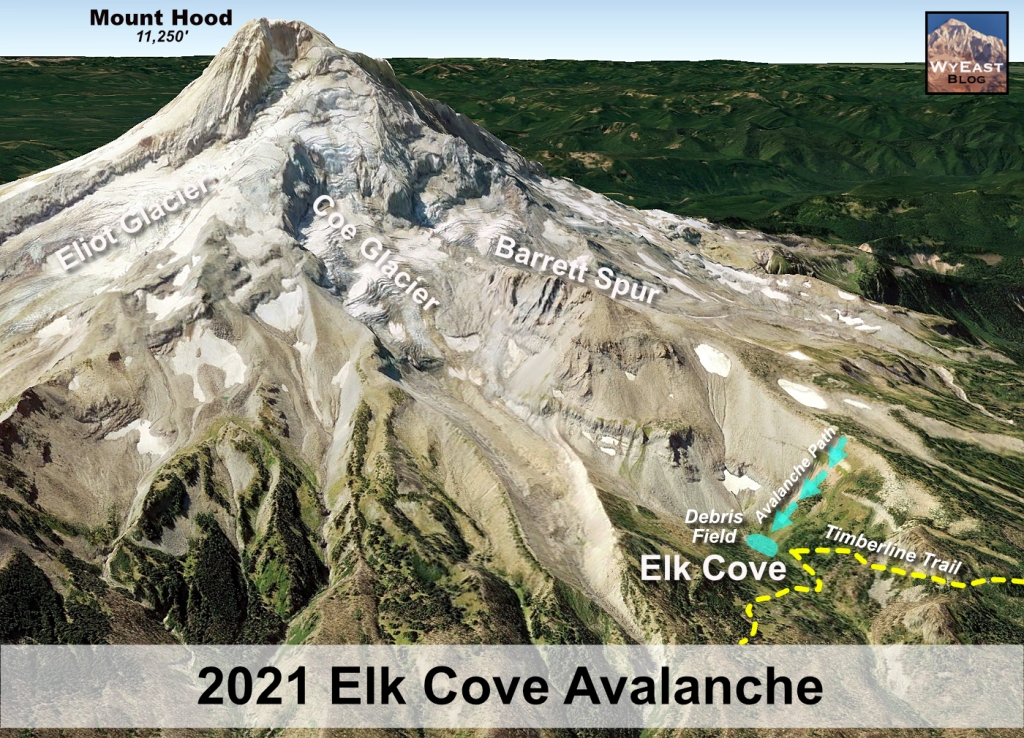

Mighty Ponderosa

Ponderosa pines are scattered throughout The Labyrinth, with some of the largest, most stately trees growing in the upper meadows, well above the Missoula flood zone. While these trees are completely adapted to periodic, low-intensity fire with their protective, fire-resistant bark and high limbs, the Burdoin Fire managed to reach the crowns of several of the largest Ponderosa along the Labyrinth Trail, revealing the intensity of the fire. Most of these trees still hold green foliage, but their loss of living canopy will slow their growth for many years, and some may not survive the loss of foliage over the long term.

Smaller Ponderosa pine are highly vulnerable to fire, as they haven’t had time to build up a protective bark layer and their foliage is still close to the ground, creating an easy “ladder” for fires to climb into their canopy. Thus, many of smaller Ponderosa along the Labyrinth Trail were killed by the fire. Unlike their adaptive oak neighbors, pines don’t grow new shoots from their roots, so it will be up to the surviving large Ponderosa to re-seed the area in the aftermath of the fire.

This big Ponderosa pine in the hearth of the Labyrinth lost most of its foliage to the fire due to a “ladder” of low limbs that allowed the fire to climb into its crown. Ponderosa have evolved to thrive with frequent, low-intensity fire, shedding their lowest, scorched limbs to become even more resilient for the next fire event. In the absence of regular fires, this big Ponderosa matured with its lower canopy fully intact, exposing it to a crown fire when an intense burn like the Burdoin Fire finally arrived. If this tree survives, it will take many years to build enough new canopy to bring the tree back to health.

This young trailside Ponderosa didn’t have a chance, but upon closer inspection…

…a pair of young oaks sharing space with the pine are already pushing up new shoots from their surviving roots, a super-power that allows oaks to quickly bounce back after fire in the East Gorge..

This young Ponderosa passed the test, sacrificing lower limbs to the fire, yet retaining its crown. Eventually shedding those killed lower limbs will help the tree survive future fires.

This large Ponderosa in the Labyrinth, with its tall canopy and high limbs, seems to have survived a hot spot in the fire that was intense enough to kill most of the oak grove that surrounds it. This pine might be old enough to have experienced wildfire in the distance past, before aggressive fire suppression began.

These large Ponderosa in the upper meadows enjoy deep soils and better growing conditions than the rocky Labyrinth areas, below. The large tree at center has clearly survived and been made more fire resistant in the future by losing its lowest limbs to the fire.

A closer look at this tree shows that both of its young offspring still have some green foliage, and have a chance of surviving, as well.

From the west, this towering Ponderosa at the top of the Labyrinth Trail seemed to fare reasonably well at first glance, losing a few of its lower limbs to the heat. However…

…the entire east side of its canopy burned, nearly to the top of the tree, providing an example of the ladder effect on large trees that retain limbs within the reach of fire. The fact that this tree had low limbs also suggests that it has not faced a wildland fire in its many decades of growing here, if ever. Though this tree lost at least half of its canopy, the crown is intact and the tree stands a good chance of slowly recovering over time.

A closer look at the base of this big pine shows a wide charred area where meadow perennials have haven’t bounced back. Why? This blackened area marks where a dense patch where the accumulation of understory brush and fallen debris fueled the fire long and hot enough to climb into the canopy of the big pine and kill the roots of the understory plants. This is a good example of how savannah fires can convert woodlands and brushy areas back to grassy meadows.

This group of young pine skeletons were offspring of the big pine and part of the brush and fuel buildup that put the large tree at risk. Crowded Ponderosa pine seedling colonies like these were among the hardest hit by the Burdoin Fire.

Understory Heroes

Beneath the canopy of those big keystone tree species are a multitude of shrubs, small trees, wildflowers, ferns and grasses that complete the savannah ecosystem in the East Gorge. Like the oaks and pines, these species are also well-adapted to fire, relying upon it for their periodic renewal.

This is most evident with perennial wildflowers, ferns and grasses that had already begun to emerge on charred, black slopes in a carpet of bright green, quickly sprouting from their surviving roots soon after the first fall rains arrived in September. Our mild winter (thus far) has only helped them continue to slowly grow and recover ahead of the spring growing season.

Native shrubs were also largely torched by the fire, though the roots of many survived and have also begun to regrow, renewing themselves with young vigorous stems that will replace old, woody thickets. For these plants, periodic low-intensity fire is an essential rejuvenator in the savannah environment.

Oregon grape respond well to fire, pushing brilliant, vigorous new foliage up from its roots within weeks to replace burned thickets of old stems.

These emerging Oregon grape stems are surrounded by wildflowers and grasses that are also recovering quickly throughout the Labyrinth.

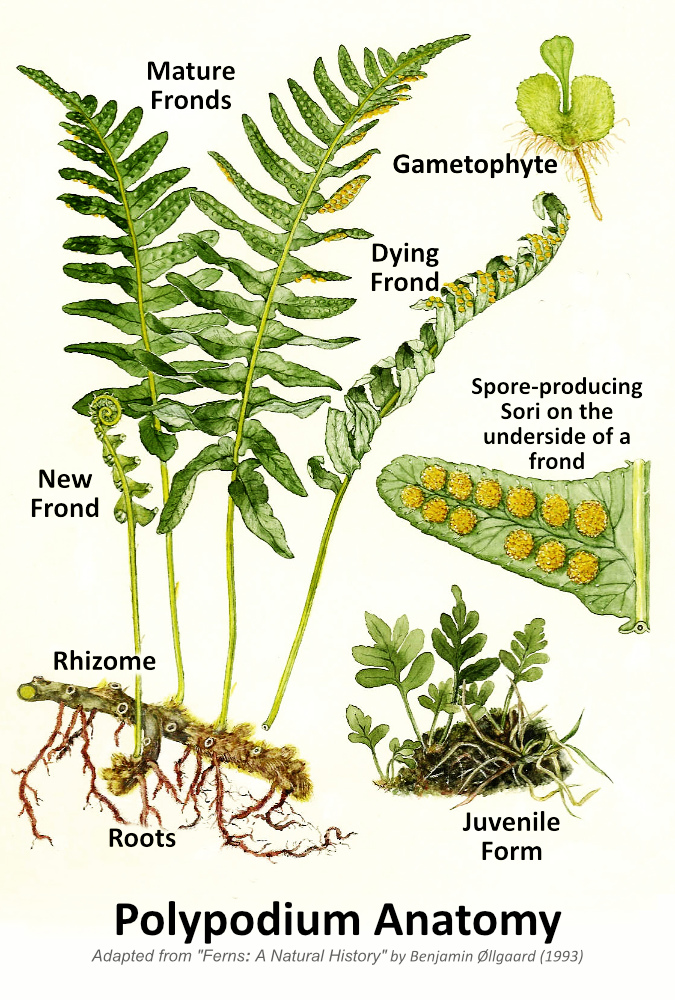

Ferns in the Labyrinth are mostly dormant in the dry months, dropping their foliage when the summer drought begins, then re-emerging for the winter months when rains return in fall. This timing worked well for these Polypodium ferns, whose underground rhizomes survived the heat and are already pushing up another season of winter fronds.

The fire was hot enough in this spot to kill a thick layer of moss where it bordered a boulder in this view, yet the dormant fern rhizomes underneath survived to push up tiny new fronds once cool fall temperatures and rain showers returned to the Labyrinth.

Invasive plants are opportunistic and can take hold after fires like the Burdoin. This invasive blackberry was already here, however, and is quickly rebounding.

One of the surprising effects of fire in the East Gorge is how meadow rocks superheat from the flame, holding their heat long enough to kill the roots and seeds in the soil around them. This ring-of-death effect is common throughout the open savannah areas of the Burdoin Fire.

The moss on this large boulder tells a unique story: the fire burned low and fast here, enough to kill the moss on the 2-foot high face of the boulder, yet not sweep over it – and not hot enough to kill the roots and seeds in the soil that are already emerging.

Among the recovering shrubs is the nemesis of Gorge hikers, our native Poison oak. Beyond its toxic quality that makes it a bane to humans, this is an important understory species for wildlife who don’t mind is toxins, relying upon it for cover and forage. Deer are immune to its urushiol oil, and browse the foliage from spring through fall and its stems in winter. Birds feed on its attractive (if toxic to us!) berries. The ability of Poison oak to quickly bounce back from fire may be bad news for hikers, but it’s good news for wildlife and the health of the larger ecosystem.

If it didn’t make us itch, we’d grow it in our gardens. Useful to all but humans, these Poison oak are bouncing back with vigor from their surviving roots and underground stems. Sorry, hikers!

Two old icons…

These are two Oregon white oak giants along the Labyrinth Trail that I would be remiss if I did not report on, as they are well-known to hikers, and are truly impressive trees.

This sprawling oak (below) is not far from the trailhead, with an infamous long, horizontal limb (on the left) that is low enough to make many hikers duck as they pass under it. The trail curves under the limb, then through a gap in the rocks just behind the tree, making this a memorable spot on the trail.

This familiar oak with his head-bumping lower limb looks to have survived the fire largely intact.

Looking down the long head-bumping limb from behind the oak reveals a burn scar on the back of the trunk that will likely become a hollow someday if the tree is unable to close the wound with new bark.

A sign of new growth to come in spring, healthy, fallen leaves and fully developed acorns give reason for optimism that the head-bumping oak will leaf out once again this spring.

Like most of the fire-impacted oaks, we won’t know for sure if this big tree has survived until spring. The fire burned hot enough here to completely clear the understory and all debris, right up to the rocky outcrop beyond the tree, leaving a burn scar on the tree’s trunk in the process. However, its limbs do seem to have sprouted some late season growth, giving a hint that it will survive largely intact, ready to bump more hiker heads for years to come.

A second iconic giant is just a few dozen yards uphill from the first big oak, and it fared quite well. As you can see in this image (below), the trail served as a fire break of sorts, and this very old tree seems to be largely untouched by the flames — though the heat many have scorched some of its lower limbs that hang above the blackened area on the slope to the right.

This giant, old trailside oak seems to have survived the fire almost completely unscathed.

Had the fire reached the base of this ancient oak, it could easily have found its way into the heart of the tree, as its trunk holds numerous large cavities that are part of what make this tree so iconic.

Next up: Catherine Creek West

Part two of this 3-part series will focus on the western savannah of Catherine Creek and the Rowland Wall, an area that was hit hard by the Burdoin Fire just nine months after the Top of the World Fire had raced through. This area has a tougher story to tell, but one with important takeaways for those who love the Gorge and seek to protect this place. I’ll have this second installment posted shortly.

As always, thanks for taking the time to read this far, and for visiting the blog!

_____________

Tom Kloster | February 2026

New! Have you visited the companion WyEast Images sister blog? Have a look and be sure to subscribe while you’re there!