Mount Hood rises over the Western Juniper forests on the east side of the Cascades

One of the most startling features of the Cascade Range comes from the rain shadow effect the mountains have on approaching Pacific storms. Through a process known as “orographic lifting”, weather systems rolling in from the ocean are forced up and over the wall of mountains when they reach the Cascades. This lifting has the effect of wringing out moisture from the clouds, resulting in rainforests on the west side and deserts on the east side of the mountains.

The rain shadow effect it especially prominent in WyEast country, where the Cascade range is at its narrowest, just 50 miles wide, compared to more than 100 miles or more across in much of the range. In less than an hour traveling through the Columbia Gorge from Troutdale to Hood River, the landscape changes from deep rainforests where up to 140 inches of rain fall annually to the Ponderosa pine and Oregon White Oak forests of the east slope, where annual rainfall dips below 20 inches.

Western Juniper finally give way to desert grasslands and sage in the rain shadow of Mount Hood, where annual rainfall drops below 10 inches

In the extreme rain shadow of the Cascades, where rainfall dips below 10 inches annually, the big conifers that define our forests finally give way to a sagebrush, grasslands and a rugged desert tree, the Western Juniper. Long overlooked as “non-commercial” (meaning it is not easily harvested as saw logs), these scrappy trees have been flourishing over the past century on the desert plains and buttes east of the mountains.

Mount Hood has its own juniper forests, though they are less widespread here than elsewhere in Oregon’s high desert country. The reason for this is agriculture. Much of the rolling desert terrain east of the mountain has been cultivated for well more than a century, originally for intensive grazing, and today for highly productive wheat farming.

Western Juniper still thrives at Juniper Flat, taking hold wherever the ground isn’t actively plowed

Yet, there are still Western juniper stands sprinkled through even the most heavily cultivated areas, and as you move away from the farms and the lowlands of the Columbia River Basin — Western Juniper mostly grow above 2,000 feet elevation — there remain many thriving Western Juniper forests.

The most extensive of these is (appropriately) at Juniper Flats, located 25 miles to the southeast of the mountain, on a rocky tableland adjacent to the White River Canyon. This is typical Western Juniper country — cold, sometimes snowy winters and hot, very dry summers. The soils here are thin, resting on a bedrock of basalt. The few areas that can be farmed have been cultivated, but the rest of Juniper Flat is grazing country where Western Juniper flourish.

When Juniper Flat got its modern name from white settlers arriving on the Oregon Trail, it’s very likely the juniper forests here looked much different than what we see today. That’s because our juniper forests are on the move and expanding.

Botanists generalize juniper forests into three community types:

• Mixed forests – these are where Western Juniper are mixed with Ponderosa Pine, Douglas Fir and other big conifers on the margins of the mountain forest zone.

Large Ponderosa Pine anchor this mixed forest, surrounded by lighter green Western Juniper that take on a tall, slender form in mixed forests

• Juniper forests – these occur where Western Juniper dominates and the trees grow relatively close together, with a canopy that typical covers 10-20% of the landscape

Juniper forest on the march at Juniper Flat where these trees are recolonizing a fallow farm field

• Juniper savanna — where Western Juniper are widely scattered in desert grasslands and their canopy covers less than 10% of the landscape

Juniper are widely scattered across this savanna in the shadow of Mount Hood, along the west edge of Juniper Flat

Scientists have documented an exponential increase in Western Juniper growing in Oregon since the late 1800s, in many cases transforming former juniper savannah to become juniper forests. This was likely the case at Juniper Flat, and today it mostly qualifies as a juniper forest.

In a landmark report published in the late 1990s, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) found that over half of Oregon’s juniper forests we established between 1850 and 1900. Still more startling is the spread of Western Juniper since the 1930s, when the first comprehensive assessment was made. At the time the BLM study was released in 1999, an estimated a five-fold increase in juniper forest coverage had occurred over the previous 60 years.

That number of Western Juniper in Oregon continues to increase today, though there is an upper limit for these trees. Their sweet spot is desert lands above 2,000 feet elevation and between 10” and 20″ of annual rainfall. They do not seem to spread much beyond these areas, and in Oregon they are now present across most areas that meet these criteria.

Western Juniper berries are a critical winter food source for coyotes, foxes, rabbits and many desert bird species. These are also the berries the Dutch famously learned to distill in the 17th Century to make gin (a word derived from the Dutch word “jenever” for juniper), and a craft distillery industry using these berries has emerged in Oregon

Western Juniper foliage is evergreen and made up of tiny, overlapping scale-like leaves that help these trees conserve moisture in their harsh desert habitat

Western Juniper bark is tough, shaggy and fire-resistant, allowing larger trees to survive moderate intensity range fires

Given their recent spread in Oregon, Western Juniper forests are also remarkably age-diverse when compared to the even-aged stands we often see with young conifer forests. A typical juniper forest contains a diverse range of trees, from young to old. These trees are tough survivors, with fully one quarter of Oregon’s juniper forests more than a century old, and over a third of these forests have century-old trees in their mix.

Why are Western Juniper forests spreading? One answer is lack of wildfire in the ecosystem over the past century due to human fire suppression. Another could be effects of climate changes that scientists are only beginning to understand. Still another is the parceling and residential development of our desert lands, and a shift away from farming and ranching, where juniper forests were routinely cleared or burned.

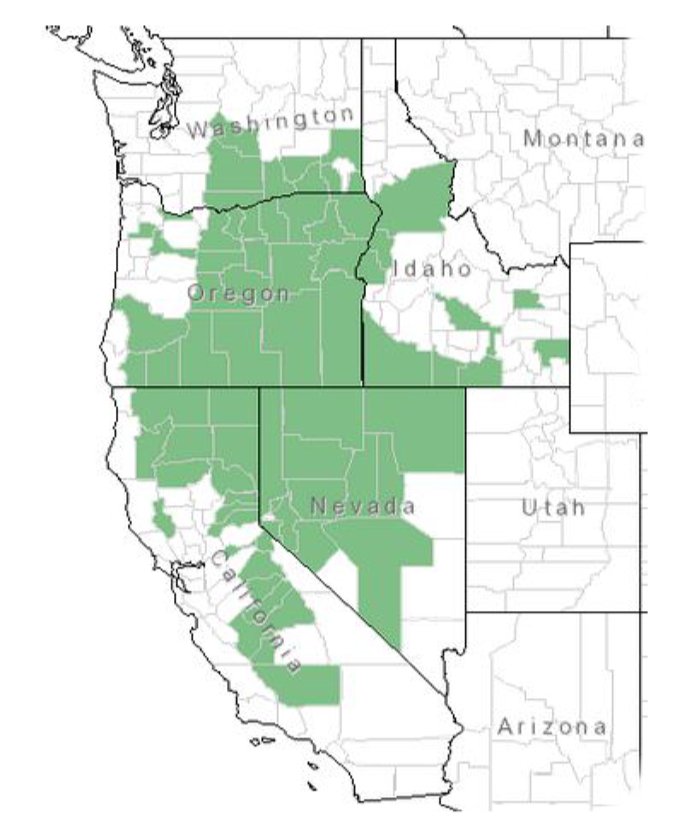

Most think of Nevada as the heart of Western Juniper country, but more than three quarters of Oregon falls within its range, and a good share of California, Washington is also prime habitat for these rugged trees

As desert survivors, Western Juniper have adapted in ways that help them out-compete with other desert plants. They have enormous root systems that can extend several times beyond the size of their crown, spreading up to two and half times the height of the tree in all directions, compared to most trees with root systems roughly proportional to the width of their crown. This helps explain the wide spacing of Western Juniper. Where our big mountain conifers often grown just a few feet from one another, juniper forests might have as few as ten trees per acre, thanks to their huge root systems.

Western Juniper crowns are also part of their competitive strategy. Their dense foliage is estimated to capture more than half the precipitation that falls upon them. Some of this is absorbed, some evaporates, but the net effect is less moisture making it to understory plants or the soil.

The small Western Juniper on the left will have to work hard to complete with its larger neighbor for water and soil nutrients. Juniper are highly efficient in their ability to gather and store moisture, out-competing other species and even their own seedlings to survive

Juniper root systems also out-compete the desert understory species that are most associated with juniper forests. These include several sagebrush species, Bitterbrush, Rabbitbrush and a few other hardy desert shrubs, along with desert grasses and wildflowers. This has emerged as a chief concern for the BLM, since this translates into impacts on the cattle industry that leases federal grazing allotments. Beyond the economics of cattle grazing (and more importantly), the loss of understory also has impacts that ripple through wildlife populations, as well.

Another concern with the spread of our juniper forests is the potential risk to private property and human life from wildfire. Western Juniper is adapted to fire, and large trees are likely to survive low-intensity fires, but they can also burn hot when conditions are right. If juniper forests have spread rapidly in Oregon’s deserts over the past century, human development in juniper country has spread still faster, placing tens of thousands of rural homes at risk to wildfire.

This BLM fuels reduction work removed about one third of the trees in this juniper forest – mostly larger trees. The cut wood and limbs are simply stacked and left to decompose. The goal is to mimic the effect of fire in maintaining and open forest and understory that might otherwise be pushed out by juniper

These concerns have led the BLM to carry out “fuels reduction” projects in juniper forests on federal lands in Oregon as early as the late 1980s. One approach is controlled burns, a practice used in other conifer forests to reintroduce wildfire to the ecosystem after a century of aggressive fire suppression. This method ideally leaves the largest junipers standing and thins out younger trees, and it has been used successfully throughout juniper country. However, fires sent intentionally continue to be a controversial practice, as evidenced by the massive New Mexico wildfires currently burning that were ignited by controlled burns. In the era of climate change, land managers will need to revisit “safe” seasons for using this tool or risk public backlash that threatens to ban the practice completely.

Another approach to “fuels reduction” is simply cutting down trees and leaving them behind as debris piles, as pictured above. This approach works where there isn’t enough understory to support a controlled burn, or where proximity to private property makes a controlled burn too dangerous. However, it’s also labor intensive compared to controlled burns and still leaves cut debris behind as potential fuel.

In areas where these approaches were employed in the 1980s and 90s, subsequent monitoring by the BLM slowed that young juniper were already colonizing burned or cleared areas within just five years. Therefore, so long as natural wildfires are suppressed in juniper country, techniques like these will be needed in perpetuity to maintain some semblance of a natural ecosystem and to protect human life and property.

This craggy old fire survivor is surrounded by young Western Juniper quickly colonizing a former burn

This points to the larger problem of rural over-development throughout the West that continues to encroach on our forests. We’ve created a perfect storm with fire suppression and sprawling that climate change is only escalating, with whole communities now facing the risk of being swept up in catastrophic fires.

In Oregon, strict land use planning has blunted rural sprawl since the 1970s, yet some of the impetus for statewide planning was the “sagebrush subdivisions” that were already underway when legendary Governor Tom McCall railed against them in 1973. Loopholes in county zoning codes have since allowed thousands more homes to be built in the deserts of Central Oregon, in particular. For these spread-out communities that already exist in juniper country, fire prevention campaigns are encouraging those living there to “harden” their homes against fire. Yet, if you spend much time in juniper country, you know that the vast majority of homes continue to be built with wood siding and most of the older homes have highly flammable composition roofing.

Many of these areas should never have been developed as home sites, of course. And as fires continue to consume whole communities in the West, there’s a good chance that cost of fire insurance or the inability to secure home loans might prevent simply rebuilding when fires in high-risk areas do occur. We’ve seen this play out in chronically flooded areas in other parts of the country, after all. The West is still coming to grips with the permanent reality of wildfire, however, and it’s unclear if we have the collective will to say no to development in fire-prone areas like our juniper forests.

Before farming, much of the juniper country near Mount Hood looked like this – open desert grasslands and scattered groves of Western Juniper. This remnant landscape at the edge of Juniper Flat, looking north to Tygh Ridge

Meanwhile, the juniper forests continue to spread and flourish in Oregon. The situation in Wy’East country is more complex, though: much of the historic juniper habitat east of Mount Hood was converted to agriculture long ago. Yet, today, some of that ground is going fallow, whether by economic realities in a global agriculture market, or because large farm parcels are being picked up by non-farmers, reverting to native plant cover. Some fallow land is being purchased for conservation purposes, either by public agencies or conservation non-profits. If these trends continue, we may see the juniper forests spreading in Mount Hood’s shadow, too.

There aren’t great trails or developed recreation sites in Mount Hood’s juniper forests (someday, hopefully!), as much of the area is in private hands. But if you like exploring rustic backroads, Juniper Flat and nearby Smock Prairie are scenic and rich with history. Dozens of abandoned homesteads and barns, a couple old schoolhouses and some fascinating pioneer cemeteries are sprinkled along the gravel roads that crisscross the hay fields and juniper groves. Juniper Flat is located immediately west of the community of Maupin and about 125 miles from Portland, along US 197.

What a great article! An excellent blend of natural history and land use discussion.

LikeLike

I really enjoyed your thoughtful article touching on useful info outside of just the tree itself. Thank you.

LikeLike

HiTom,

I’vebeen enjoying going back and rereading your previous posts as I eagerly await anew, always fascinating, article on your WyEast Blog.

Hopeyou had many memorable times outdoors this summer.

Youare a great advocate and much appreciated.

Sincerely,

BrentDouglas

LikeLike