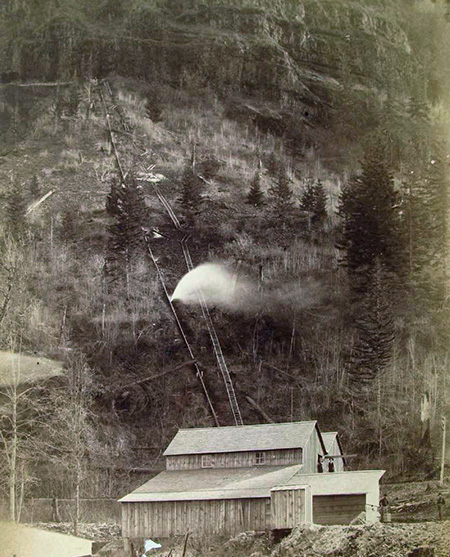

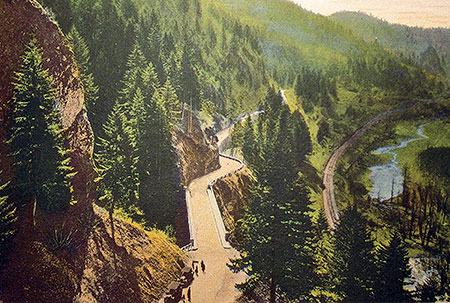

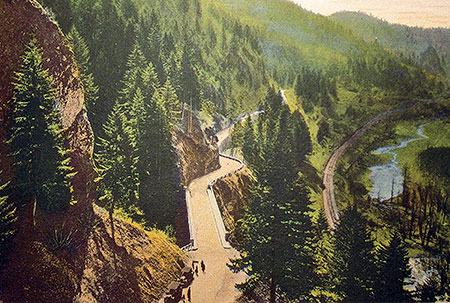

Hand-colored photo from the 1920s showing the west approach to Shepperd’s Dell

For nearly a century, countless travelers on the Historic Columbia River Highway have admired the idyllic scene that unfolds at Shepperd’s Dell, one that has also appeared on dozens of postcards and calendars over the decades.

George Shepperd’s sole memorial in the Columbia Gorge is this small plaque on the Shepperd’s Dell bridge

Yet, beyond the fanciful name and a small bronze plaque at the east end of the highway bridge, few know the story behind the man who gave this land to the public to be enjoyed in perpetuity. Who was George Shepperd? This article is about the modest farmer who gave us his “dell”.

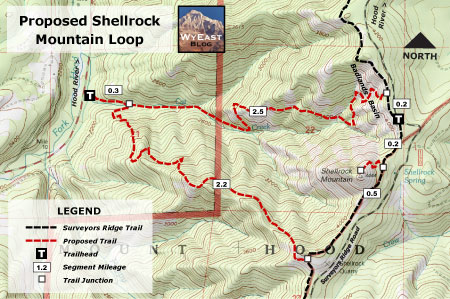

Threading the Needle

George Shepperd’s story is interwoven with the brilliant vision of a true icon in our regional history, Samuel Lancaster, the chief engineer and designer of the Historic Columbia River Highway. Had Sam Lancaster not attempted to frame sweeping views and hidden natural features at every turn with his epic road design, Shepperd’s Dell might have remained a mostly hidden secret.

Lancaster saw his new highway as something to be experienced, not simply the shortest path through the Gorge:

“…as Consulting Engineer in fixing the location and directing the construction of the Columbia River Highway… I studied the landscape with much care and became acquainted with its formation and its geology. I was profoundly impressed by its majestic beauty and marveled at the creative power of God, who made it all… [I] want [visitors] to enjoy the Highway, which men built as a frame to the beautiful picture which God created.”

-Samuel C. Lancaster (1916)

With this grand vision, Lancaster saw a special opportunity to showcase nature at Shepperd’s Dell. When approaching from Crown Point, the old highway rounds a blind corner cut into sheer cliffs, high above the Columbia when the graceful, arched bridge spanning Shepperd’s Dell suddenly comes into view.

Sam Lancaster and other dignitaries are pictured here at Shepperd’s Dell on the opening day of the Columbia River Highway in 1916

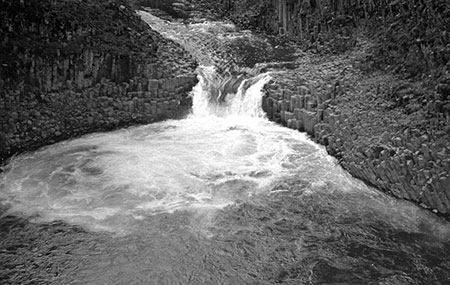

Tall basalt domes rise above the bridge, and from mid-span, visitors are treated with a view into the shady, fern-draped “dell” holding Young Creek. A graceful, 8-tiered waterfall leaps a total of 220 feet through a twisting gorge, much of it hidden from view in the mossy recesses of the dell.

In his inspired design for Shepperd’s Dell, Sam Lancaster’s threaded the needle by spanning the narrow canyon at the midpoint of the falls. By any other highway engineer of the time, this would have been a travesty, but Lancaster’s gracefully arched bridge and careful attention to detail achieves the opposite: he transformed this little grotto into one of those rare examples where man and nature meld in idyllic harmony. This artful balance is the enduring lure of Shepperd’s Dell to this day, making it a favorite stop along the old highway.

Samuel Lancaster’s iconic bridge at Shepperd’s Dell as it appears today

Sam Lancaster said this of his design for Shepperd’s Dell:

“The white arch of concrete bridges a chasm 150 feet in width and 140 feet in depth. The roadway is cut out of solid rock [and] a sparkling waterfall leaps from beetling cliffs and speaks of George Shepperd’s love for the beautiful, and the good that men can do.”

-Samuel Lancaster (1916)

Complementing the highway is a rustic footpath leading from the bridge to a viewpoint at the edge of the falls. The footpath is cut into the vertical walls of the dell and framed with Lancaster’s signature arched walls. From the falls viewpoint, the vista sweeps from a close-up of the cascades on Young Creek to the graceful arch of the highway bridge, soaring above the canyon. This is understandably among the most treasured scenes in the Columbia Gorge.

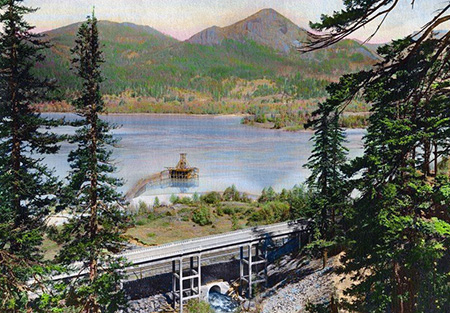

1920s postcard view of Shepperd’s Dell showing the Bishop’s Cap in the distance.

Samuel Lancaster created this scene as we experience it today, but only because George Shepperd made it possible by showing Lancaster his secret waterfall, and offering to donate his land to the highway project so that others might enjoy his dell in perpetuity.

Who was George Shepperd?

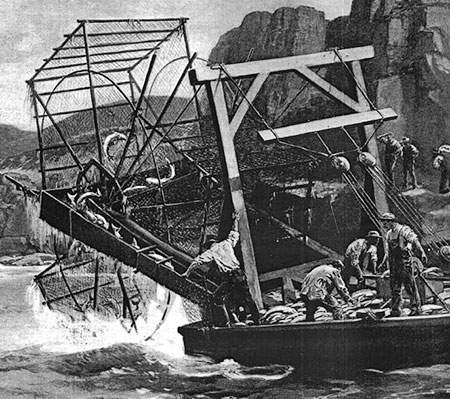

When Sam Lancaster was building his touring road through the Columbia Gorge, a number of well-to-do land owners with vast holdings in the area generously donated both right-of-way and some of the adjacent lands that hold the string of magnificent waterfalls and scenic overlooks that we enjoy today. Until the highway idea was conceived in the early 1900s, the Gorge was mostly valued for its raw resources, with several salmon canneries and lumber mills along the river and the forests heavily logged. The idea of a parkway was new, and part of the surging interest in creating national parks and expanding outdoor recreation across the country.0

Middle tier of the falls at Shepperd’s Dell as viewed from the highway bridge

George Shepperd was equally generous with his donation, but he wasn’t a timber baron or salmon cannery tycoon. Instead, Shepperd was a transplanted Canadian farmer who had moved his family here after a short stay Iowa in the 1880s. Samuel Lancaster wrote this of Shepperd:

“The tract of eleven acres at this point, given by George Shepperd for a public park, is unexcelled. God made this beauty spot and gave it to a man with a great heart. Men of wealth and high position have done big things for the Columbia River Highway which will live in history; but George Shepperd, the man of small means, did his part full well.”

-Samuel Lancaster (1916)

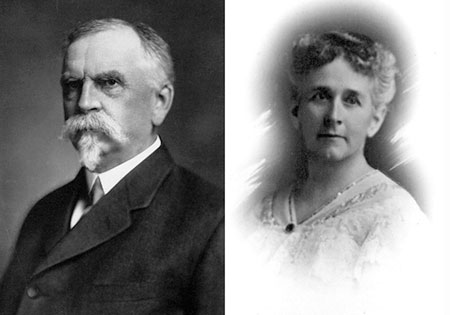

George Shepperd, his wife Matilda and their sons William and Stuart moved from Goderich Township, Ontario (roughly halfway between Toronto and Detroit) to a farm in Audobon County, Iowa in 1880, where the couple gave birth to two more sons, George Jr. and John.

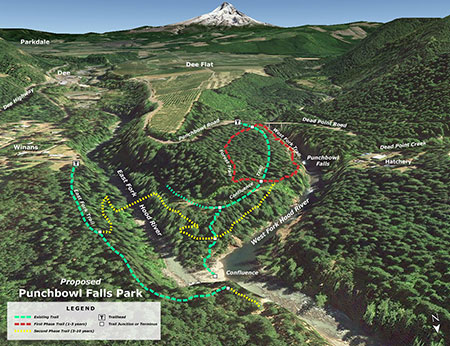

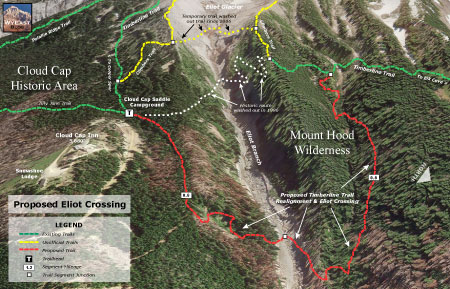

George Shepperd’s extensive holdings in the early 1900s were mostly hills and ravines (shown in yellow), with the donated Shepperd’s Dell parcel shown in green. Much of Shepperd’s remaining land has since been brought into public ownership

In 1889, the Shepperds moved again, this time to Oregon where they settled in the Columbia River Gorge on a 160-acre land claim along Young Creek, just west of the mill town of Bridal Veil. Their fifth child, a daughter named Myra, was born just a year after they arrived, in November 1890. Upon settling in Oregon, George Shepperd supported his family by farming, dairying and working at the nearby Bridal Veil Lumber Mill.

At this point in history, the George Shepperd story becomes complicated: in May 1895, George and Matilda divorced, and in January 1896, George married Martha “Mattie” Maria Cody Williams, who had also recently divorced. Mattie apparently met George when the Shepperd and Williams families had traveled west to Oregon together in 1889. The “Cody” in Mattie’s lineage was indeed William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody, a first cousin.

The view today from Shepperd’s Dell toward Crown Point includes some of George Shepperd’s former pasture lands, now in public ownership and managed for wildlife.

George Shepperd was 47 years old when he married 37 year-old Mattie in 1896, and while the first years of their new marriage seemed to have been blissful, the next 35 years of his life were a rollercoaster of tragedies and triumphs.

The tragedy began in 1901 when his eldest son, William J. Shepperd, boarded a train to Portland to pick up supplies for the business he and his brother George Jr. had in Hood River. William reportedly waved to friends and family from the rear platform as he passed through Bridal Veil and the Shepperd farm, then was never seen again.

Local news accounts speculated that William had been “Shanghied” while in Portland and taken aboard a foreign cargo ship. Ten years later, William’s surviving wife Osie and son Raymond also disappeared after living with the Shepperds and members of Osie’s family in Portland for several years. They were never heard from again by George Shepperd.

The Bridal Veil Historic Cemetery is tucked among the trees near the Angels Rest trailhead

More tragedy ensued in 1903, when George Shepperd lost his beloved Mattie, just seven years after the two had married. There is no record of why she died, though some accounts describe her as “crippled” in those years. She was only 44 years old.

If the impressive memorial he erected for Mattie at the Bridal Veil cemetery is any indication, George was profoundly heartbroken. He never married again. The melancholy epitaph at the base of her grave marker reads:

“One by one earth’s ties are broken, as we see our love decay, and the hope so fondly cherished brighten but to pass away.”

The infant grave of Elizabeth Dutro is also located within the otherwise empty Shepperd family plot, next to Mattie’s grave and dated October 15, 1903 – seven months after Mattie was buried. Baby Dutro seems to be Mattie’s granddaughter by Bertha Delma Williams Dutro, her daughter from her first marriage. Bertha Dutro lived until 1963, and had two more daughters. She is buried at the Idlewildle Cemetery in Hood River.

Mattie Shepperd’s grave marker at the Bridal Veil Cemetery

Mattie Shepperd, “wife of George Shepperd”

The tiny Bridal Veil Cemetery is still maintained and open to the public, though a bit hard to locate: an obscure gravel driveway drops off the north shoulder of the I-84 access road at Bridal Veil, just below the Historic Columbia River Highway. A number of early settlers from the area are buried in this lonely window into the past.

Baby Dutro was laid to rest a few feet away and nine months after Mattie Shepperd

Over the next few years, George Shepperd must have met Samuel Lancaster as the engineer began his surveys of a possible highway route through the Gorge. Travel in the Gorge at that time was mostly by train, and the Shepperd farm was one of the many stops along the route. No record of their meeting exists, but George was described as an early supporter of the highway, and this is surely the time when he realized that he could be part of Lancaster’s grand vision.

Some accounts suggest that the sudden loss of Mattie was also part of George Shepperd’s motivation to leave a lasting legacy with a land donation, but there is no record of this. Instead, it was simply the beauty of Shepperd’s Dell that seemed to motivate him.

Newspaper accounts also show that Shepperd had many opportunities to sell his property for substantial profit, as the new highway was quickly dotted with roadhouses and gift shops aimed at the new stream of tourists. The Oregonian later reported: “ever since the highway was constructed, Mr. Shepperd has received offers to purchase the tract, but has refused them, having in mind an intention to dedicate the property to the use of the public.”

Early 1930s postcard view of Shepperd’s Dell.

In March 1914, George Shepperd’s land donation along Young Creek was announced as part of the construction of the Columbia River Highway. But by late 1915, Shepperd was involved in a legal dispute with a neighboring landowner who attempted to take claim to the land he had donated – the land that is now Shepperd’s Dell. By 1916, George Shepperd was counter-suing on grounds of fraud to clear the title – one that stemmed from a loan that one of Shepperd’s sons had taken years earlier. The Oregonian reported the events with the headline “Good Deed Spoiled” as a nod to Shepperd’s noble intentions:

“A few years ago, the elder Mr. Shepperd, owner of an 80-acre piece of land above the Columbia River, deeded 10 acres, including the famous Shepperd’s Dell, to the City of Portland as a public playground. The Columbia River Highway was being built and it was apparent to Mr. Shepperd that this attractive place would be a valuable possession to the city. While he was a comparatively poor man, he determined, instead of selling the property for a small fortune that he could have received for it, give it free of cost to the public.”

(The Oregonian, March 16, 1916)

Thankfully, Shepperd prevailed in the legal dispute. At that point in the dramatic early history of the new highway, the Shepperd’s Dell section of the road had already been constructed, but who knows what might have been built there had the land slipped away from public ownership?

In November 1915, George Shepperd was fighting a second legal battle, joining the City of Portland in a lawsuit against the Bridal Veil Lumber Co., and their plan to divert Young Creek away from Shepperd’s Dell and into a generating facility to provide power for their mill. The City and Shepperd prevailed in this suit, as well.

This is the only known photo of George Shepperd. It appeared in the Oregon Journal in 1915.

George Shepperd’s personal roller coaster continued on June 8, 1916, when he found himself seated among the most honored guests at the spectacular dedication of the Columbia River Highway at Crown Point. Shepperd was recognized in the formal program along with historical luminaries like Sam Hill, Samuel Lancaster, Julius Meier, Simon Benson and John B. Yeon. The ceremony was kicked off audaciously by President Woodrow Wilson unfurling an American Flag remotely by pressing a telegraph button in the White House, surely a highlight for a modest farmer from Canada.

Though surrounded by millionaires and elite scions of Portland’s old money at the grand opening, Shepperd stood apart from his honored peers that day: John B. Yeon, who had been appointed roadmaster in the campaign for the Columbia River Highway project, summed it up best:

Mr. Shepperd’s donation is worthy of the highest praise, especially in view of the fact that he [is] not a wealthy man. He has made a sacrifice for the public good that ought to make some of our rich men ashamed of themselves.

John B. Yeon, Oregon Journal, April 23, 1915

Close-up view of the vehicle carrying Sam Lancaster as he passed Shepperd’s Dell during the grand opening of the Columbia River Highway in June 1916.

In an earlier 1915 front-page feature previewing the new highway (still under construction), the Oregonian described Shepperd’s Dell this way:

“One of the wonder spots on the Columbia Highway, in the daintiness and sublimity combined with its scenery is Shepperd’s Dell, which was donated to the highway as a public park by George Shepperd, because he loved the spot and because he wanted it preserved forever for the enjoyment of people who come along the highway.

Mr. Shepperd is not a rich man and his donation is one of the most noteworthy in the history of the highway. At Shepperd’s Dell is one of the finest bridges on the highway and a trail has been built leading down from the highway to the dell and back to the beautiful little waterfall and springs in the gorge. The view back from the trail, looking through the arch made by the concrete span, is one of the most beautiful on the highway.”

(Sunday Oregonian, August 29, 1915)

George Shepperd’s Final Years

This home on NE Stanton Street in Portland is where George Shepperd lived out the final years of his life.

In 1917, sixteen years after his eldest son William had vanished and six years after William’s wife Osie had disappeared with his grandson Raymond, George Shepperd sought foreclosure on 120 acres of land he had given to the young couple shortly before William disappeared in 1901. The title was cleared by April 1919, and Shepperd promptly donated the land, including a four-room farmhouse, to the local YMCA. The YMCA reported that the house and property would be converted into a model boys camp and lodge:

“A party of boys will visit the place today to clear off sufficient land for a baseball diamond and athletic field and to commence the work of remodeling the lodge. The camp will be used by the boys this summer for short camping trips, covering a period of only a few days, and is especially intended for use of those boys who are unable to devote the time required to make the trip to the regular summer camp at Spirit Lake.”

(The Oregonian, April 4, 1919)

By 1920s, George Shepperd had finally retired from his farm at Shepperd’s Dell, having survived his second wife Mattie and a remarkable series of peaks and valleys in his life. He moved to Portland, and lived there until passing away at his residence on NE Stanton Street in July 1930.

George Shepperd’s modest grave marker at Riverview Cemetery.

Shepperd left an estate of about $8,000 to his remaining sons and daughter, primarily property in the Shepperd’s Dell area. But he hadn’t forgotten his missing grandson Raymond, and left him a token “five dollars in cash”, (about $70 today) presumably in hopes that the execution of his estate might somehow reconnect Raymond with the Shepperd family.

George Shepperd is interred at Portland’s Riverview Cemetery, along with many other important figures from the early period in Portland’s history. His understated gravesite is surprisingly distant from where his wife Mattie is buried in the Bridal Veil cemetery, and we can only guess as to why his surviving children didn’t bury him there.

George Shepperd Jr. in an early 1940s news account, on the right.

George’s children produced nineteen grandchildren, and the Shepperd family name lives on throughout the Pacific Northwest.

His second-oldest son Stuart lived until 1952, when the Oregonian reported that an “elderly man” had collapsed on a sidewalk in downtown Portland, apparently from a heart attack. At the time of his death, Stuart Shepperd was residing in Latourell, near the family homestead in the Columbia Gorge. His surviving brother George G. was still living in Bridal Veil at the family homestead at that time.

George G. Shepperd and his wife Emma left the Shepperd farm in 1953 or 1954 and George G. lived until 1961. George G Shepperd’s son George “Junior” went on to become a prominent officer for the Oregon Bank, and died in 1975. The youngest of George Shepperd’s four boys, John, died in 1959. Myra Shepperd, George’s only daughter and the only one of his children born in Oregon, lived until 1975.

The bridge at Shepperd’s Dell in the 1940s, complete with a white highway sign from that era.

The original 10-acre Shepperd’s Dell park was transferred from the City of Portland to the Oregon State Park system in September 1940. The state made a series of additional purchases to expand the park over the next several decades, bringing the total size of today’s park to more than 500 acres.

Today, Shepperd’s Dell State Park encompasses Bridal Veil Falls, Coopey Falls and the west slope of Angels Rest, to the east, in addition to its namesake waterfall grotto.

George Shepperd’s legacy… and ours?

Shepperd’s Dell lights up with fall colors each autumn.

Imagine the Columbia River Highway without Shepperd’s Dell, and you can truly appreciate the magnitude of George Shepperd’s generosity and vision. There’s an important lesson from his legacy: bringing land into public ownership is complicated, expensive and often messy, and thus requires great determination.

Flash forward to our times, and consider the hundreds of private holdings that still remain in the Columbia River Gorge. Then imagine the “good that men can do” (in Samuel Lancaster’s words) — what if just a few of these parcels were donated to the public in perpetuity in our time?

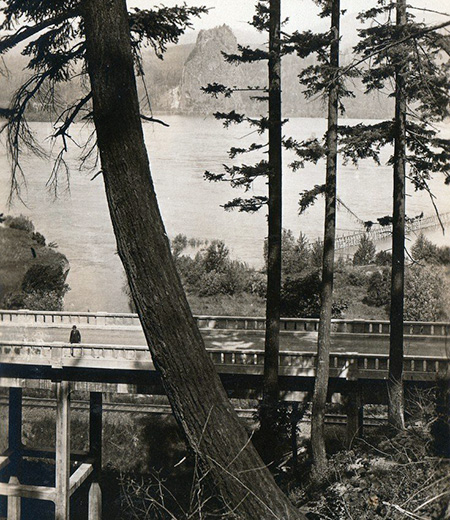

This unusual hand-colored photo from the 1920s is from the Bishops Cap, looking west toward the bridge at Shepperd’s Dell. Though the trees have grown, much of the rest of this scene is preserved today.

Hopefully, the spirit of George Shepperd’s humble generosity will live on in the hearts of those fortunate few who still hold private property in the Gorge, but we’re also fortunate to have several non-profit organizations with land trusts to help the transition along:

• The Friends of the Columbia River Gorge have become the most active in recent years in securing critical private holdings in the Gorge. Without Friends of the Gorge, we would not have secured lands at Cape Horn, Mosier Plateau of the Lyle Cherry Orchard, for example, among more than a dozen sites acquired by the Friends.

• The Trust for Public Land serves as a critical go-between in helping secure private lands for eventual public purchase. Without the Trust, we would not have secured nearly 17,000 acres in the Gorge through more than sixty separate transactions over the past 30 years.

• The Nature Conservancy continues to acquire endangered ecosystems, and their extensive holdings at Rowena Plateau and McCall Point also serve as some of the most visited recreation trails in the Gorge.

• The Columbia Land Trust is another important player in securing private lands in the Gorge, as well as the rest of the lower Columbia River. Their focus is on riparian sites and securing critical habitat.

Very few of us will ever find ourselves in the position of George Shepperd, with a waterfall or craggy viewpoint to give to the public, but we can be part of that enlightened tradition in a smaller way. Please consider supporting these organizations in their efforts to expand our public lands in the Gorge!

________________

His Heirs

The Oregon Journal • July 23, 1930

GEORGE SHEPPERD was a poor man but he gave all that he had. Without intending it he made for him a memorial that will for all time identify his name with unselfish public service.

He owned a few rocky acres in the Gorge of the Columbia. It was land from which a living could be wrested only by dint of much toil. But through it ran a small stream that at last leaped and laughed and spiraled its way down through the great basaltic cliff that was the wall of the gorge. The course of the cataract led to Shepperd’s Dell.

It was for many years George Shepperd’s habit to go on Sunday afternoon with the children and sit beneath a tree and look down upon the exquisitely fashioned spot. The harsh outlines of the rock, cast up aeons ago by volcanic fires, were softened and carved into fantastic and beautiful forms by the streamlet. Maidenhair fern clung precariously to the cliff. Flowers bloomed under the shadow of the tall and somber firs.

When the Columbia River Highway was built George Shepperd gave Shepperd’s Dell to the people as their beauty spot forever. At other points along the highway “No Trespass” signs appeared where property was privately owned. George Shepperd left a welcome.

One wonders if there will be a bright Sunday afternoon when the spirit of this humble man will be allowed to return and brood over Shepperd’s Dell and share in the pleasure of the many who revel there. Having little, he gave all, and it became much.

(Postscript: after his death the Oregon Journal published this tribute to George Shepperd. We are all still “his heirs”. I would someday like to see these words cast in bronze and tucked into a shady corner of his Dell so that a bit of his story might be known the many who visit this spot)

________________

Acknowledgements: as you might have guessed from the length, this was among the more challenging articles to research for this blog, as very little is written about George Shepperd. An especially big big thank-you goes to Scott Daniels, reference librarian at the Oregon Historical Society, who helped me locate the only known biography of George Shepperd.

The obscure Shepperd biography was written in 1997 by Muriel Thompson, a great-great niece of George Shepperd. Thompson traveled to Oregon to conduct some of her in-depth research, including court records from the various legal actions Shepperd was party to and digging into Oregon Journal archives at a time when news searches meant poring over microfiche archives. It’s an invaluable account of George Shepperd’s life and legacy.

The stairs leading into Shepperd’s Dell from the bridge as they appeared in the 1940s – the signpost no longer exists, though the rest of the scene is largely unchanged.

Thompson’s biography did not have the benefit of today’s internet research tools, and through a variety of these sources, I was able to piece together a fuller picture of George Shepperd’s complex life than was possible in 1997, especially details about his two marriages and additional historic news accounts about his land donation and the construction of the Columbia River Highway.

There is still plenty of mystery surrounding this important player in the history of the Columbia Gorge: did any structures from George Shepperd’s farm survive? Why did his children bury him at Riverview Cemetery instead of Bridal Veil, by his beloved Mattie? What became of his grandson Raymond, by his vanished eldest son William? As always, I welcome any new or corrected information, and especially contact with any of his descendents. One of the unexpected joys in writing this blog is the opportunity to connect directly with grandchildren and great-grandchildren of important people in our regional history!