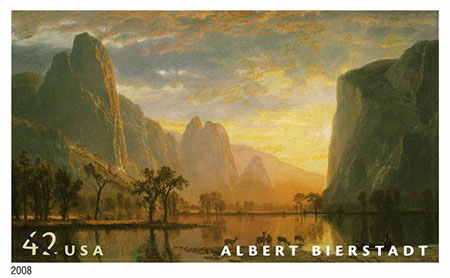

January sunset in the Eagle Creek burn, near Elowah Falls

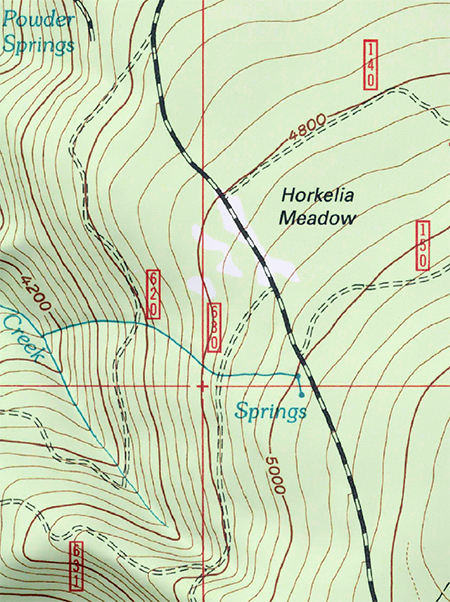

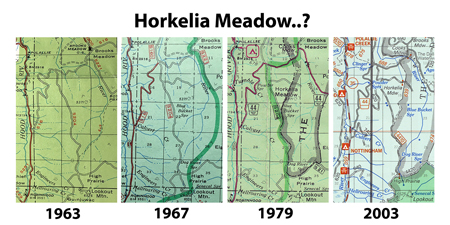

This is the second article in a two-part series that explores a remarkable set of stunning, often startling aerial photos captured by the State of Oregon in early December. Their purpose was to assess the risks for landslides and flooding from the bare, burned Columbia River Gorge slopes following the September 2017 Eagle Creek Fire. But these amazing photos also provide the first detailed look at the impact of the fire, and for those who love the Gorge, a visual sense of how our most treasured places fared.

The first article covered the west end of the burn, from Shepperd’s Dell to Ainsworth State Park. This article covers the eastern part of the burn, from Yeon State Park to Shellrock Mountain. More information on the photos follows the article.

_______________________

Ainsworth State Park and McCord Creek

This first image in this second part of the series looks east from above Ainsworth State Park, toward Bonnevillle Dam. The Gorge was heavily burned along this stretch, from the banks of the Columbia River at the community of Warrendale to the tall crests of Wauneka Point and Nesmith Ridge.

Looking east from above Ainsworth State Park toward Bonneville Dam (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

The huge amphitheater along the Nesmith Point trail is on the right in the above view, and appears to be heavily burned. Little-known Wauneka Point is in the upper left corner of the photo, and also appears to be badly burned, as shown in a close-up view (below):

Scorched Wauneka Point after the fire (State of Oregon)

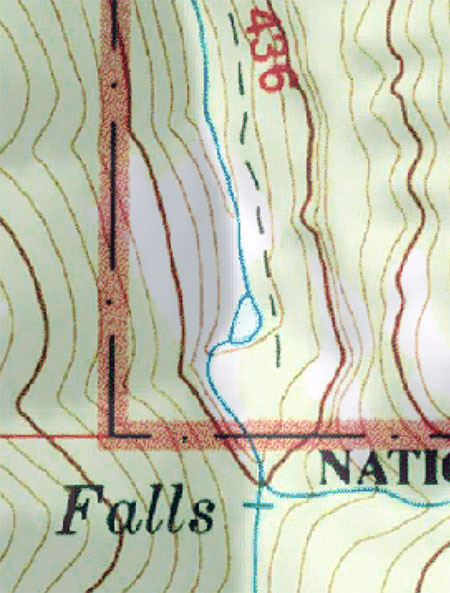

Wauneka Point is notable for its remoteness. Some reach this spot by scaling the ridge from nearly 3,000 feet below, at Elowah Falls, while others follow the faint Wauneka Point Trail from the headwaters of Moffett Creek. This is fortunate, as the rocky outcrop of Wauneka Point also has one of the most elaborate and unusual Indian pit complexes found in the Gorge.

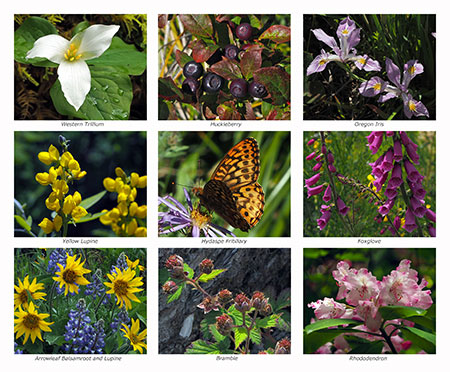

Fires here are a regular occurrence, too — photos from the early 1900s show a recovering forest and hundreds of bleached snags along Wauneka Ridge, much as the ridge now appears after the Eagle Creek Fire. It’s likely that Native Americans living along the lower Columbia River periodically burned these ridge tops to promote huckleberry, beargrass and other sun-loving foods and materials that were gathered in the higher elevations of the Gorge.

Another detailed look at this photo helps explain why parts of the Upper McCord Creek Trail were so heavily impacted by debris after the fire. This close-up view (below) shows extensive landslides on the slopes above the trail that have released tons of loose rock and debris onto the section of trail that switchbacks up the slope beneath the cliff band. While slides like these will eventually be stabilized by recovering forests, more debris is certain in the near-term, as the forest understory begins to take hold.

Landslides on the slopes above the Upper McCord Creek Trail (State of Oregon)

Another detail that emerges from this photo is the widely varied pattern of a “mosaic” fire, from blackened, completely burned forests to green, intact conifer stands that have survived the initial heat and stress of the fire. A closer look (below) at a section of forest that straddles the Nesmith Point Trail shows a heavily burned area in the center, surrounded by surviving forest.

Mosaic burn patterns straddling the Nesmith Point Trail (State of Oregon)

This mosaic burn pattern is beneficial for the forest ecology, as it rejuvenates the understory where the canopy has survived, while creating forest openings that will eventually create a more diverse forest where the burn destroyed old canopy:

This close-up view (below) shows the McCord Creek delta, where it enters the Columbia River:

McCord Creek Delta (State of Oregon)

Tributary deltas like these are likely to grow significantly throughout the Eagle Creek Burn area in coming years as erosion from burned slopes loads up the creeks with extra rock and gravel. This is another beneficial aspect from the fire cycle, with gravel deltas and debris in streams providing some of the best fish and riparian habitat in the Gorge.

This spectacular image (below) from the State of Oregon series captures the massive amphitheater that holds Elowah Falls, on McCord Creek. The twin cascade of Upper McCord Creek Falls is also visible, just above Elowah Falls, as well as the bridges of I-84, the Union Pacific Railroad and the recently built Historic Columbia River Highway State Trail:

Elowah Falls and McCord Creek (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

Though much of the McCord Creek drainage was badly burned in the fire, some of the tree canopy survived, especially the tall conifers that grow along the creek below Elowah Falls (below).

Elowah Falls after the fire (State of Oregon)

We won’t know the fate of the beautiful Bigleaf maple groves that line the creek in the lower McCord Creek canyon until later this spring, but it’s unlikely their crowns have survived. Unlike Douglas fir and other conifers, maples lack thick, insulating bark needed to survive the heat of the fire, nor the height to protect their upper branches from the flames. Instead, maples have evolved to simply regrow from their surviving roots after fire, often forming multi-trunked trees with a circle of shoots that emerge from around the skeleton of the parent tree.

Elowah’s graceful Bigleaf maple groves in autumn, lighting up the forest in 2014

While many riparian strips within the Eagle Creek Burn resisted the fire, some of the steepest slopes along McCord Creek below Elowah Falls (below) were badly burned. The geology of this section of the canyon doesn’t help the cause, as it consists of loose, slide-prone Eagle Creek Formation clays and gravels. This notoriously unstable formation is responsible for most of the ongoing slides and collapses that occur in the Gorge, including the epic Table Mountain landslide that briefly created the fabled Bridge of the Gods in 1450 A.D., near today’s Cascade Locks.

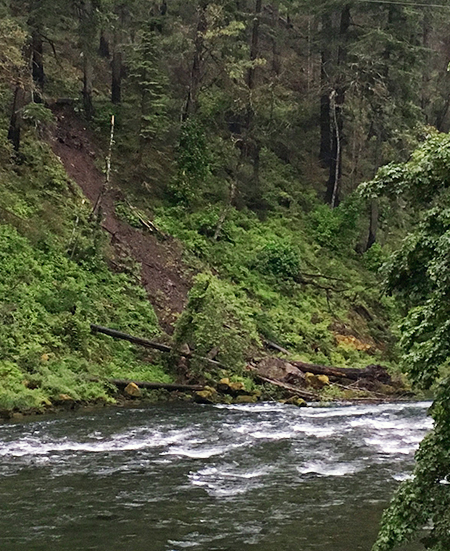

Slide-prone McCord Creek below Elowah Falls (State of Oregon)

On a recent tour of this section of the McCord Creek Trail with State Park officials, it was clear (below) that a complete re-route of this iconic trail may be needed over the long term if this already slide-prone section of the trail further deteriorates as a result of the fire:

Post-fire landslide damage below Elowah Falls

As difficult as it is to absorb these images of devastation from the Eagle Creek Fire in places like this, it’s also an opportunity to watch and learn from the forest recovery that is already underway. While I won’t see tall groves of mossy Bigleaf maples arching over McCord Creek again in my lifetime, many of today’s Millennials will live to see a substantial return of forests across much of the Eagle Creek Burn.

Beautiful McCord Creek canyon before the fire; today’s Millennials will live to see young forests like this return to the Gorge in their lifetime

This photo provides a even closer view of the Elowah Falls amphitheater and Upper McCord Creek Falls:

Elowah Falls after the fire (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

The fire was more intense in the McCord Creek canyon, above Elowah Falls, including these slopes (below) above Upper McCord Creek Falls, as this close-up view shows. Here, the trail can be seen on the bare slope adjacent to the falls:

Upper McCord Creek Falls after the fire (State of Oregon)

Here is a closer look at Upper McCord Creek Falls from a January visit with State Park officials that confirms the devastating impact of the fire here:

Upper McCord Creek Falls in January

Few trees survived in this area, and erosion is severe in several of the small streams that flow into McCord Creek from Nesmith Ridge. Yet, even with the devastation from the fire, signs of the recovery were already apparent in January, just four months after the fire, with new vegetation emerging in the middle of winter.

The burned riparian forest along the upper section of McCord Creek included 50-60 year old stands of Bigleaf maple and Red alder, and both species appear to have been killed by the fire. Unlike maple, the alder stands are less likely to regrow from surviving roots, and instead mostly rely on new seedlings. Red alder are uniquely adapted and prolific at this, and are among the first trees to colonize burned or disturbed areas.

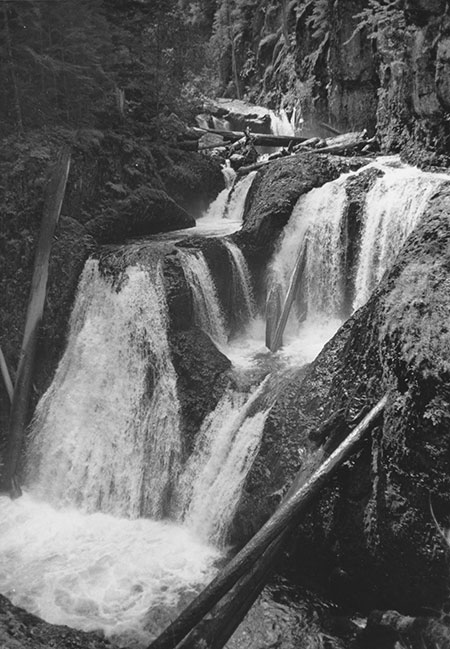

Upper McCord Creek Falls framed by Red alder before the fire

Still considered a “weed tree” by a timber industry more interested in lumber than healthy forests, these trees (and other pioneering, soil-stabilizing broadleaf species) are still sprayed with herbicides in recovering clearcuts to allow rows of hand-planted Douglas fir seedlings to grow, instead. Yet, Red alder are an essential species in the process of natural forest recovery in the Pacific Northwest. While the big conifers will take many decades to once again tower above McCord Creek, a scene with Red alder framing the creek, like the one shown above, may be just 20-25 years in the future if they are allowed to grow.

As an early colonizer, Red alder not only help to quickly stabilize exposed soils, they also serve as a nitrogen fixer, restoring 80-200 pounds of nitrogen per acre through their roots when pioneering a disturbed site. As the forest recovery unfolds in the Eagle Creek burn, these humble trees will stabilize some of the toughest terrain and help other species that follow become established in the rich soil they create. This process may not be the fasted way to grow lumber, but it’s the most sustainable way to ensure the long-term health of our forests.

This photo from the State of Oregon series shows a mostly scorched forest in the upper McCord Creek canyon, with only a few surviving trees:

Upper McCord Creek canyon (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

A closer look at the photo shows a few surviving bands of forest that will help begin the recovery. This section of surviving trees will also help shade a section of McCord Creek as other, more heavily burned parts of the watershed recover:

Patches of surviving forest along upper McCord Creek (State of Oregon)

This photo also provides another peek at Wauneka Point, mostly burned but with a few surviving tree stands that will help restore the forest on this ridge:

A few surviving trees at Wauneka Point after the fire (State of Oregon)

The faint, historic trail to Wauneka Point from the Moffett Creek trail was already in jeopardy of being lost to lack maintenance and use, and sadly, the fire may seal its fate in becoming another “lost trail”. Debris from burned trees will quickly overwhelm the path without some periodic maintenance, something that has not occurred here for many years.

The burn provides an opportunity to rethink trails like the one on Wauneka Point, including making new connections to allow hikers to more easily use them from more accessible trailheads along the highway corridor.

Moffett Creek, Munra Point and Tanner Creek

Moving east of Wauneka Point, the next photo of the Eagle Creek Burn provides a glimpse into remote Moffett Creek canyon, one of the wildest, most untouched places in the Columbia River Gorge:

Moffett Creek canyon after the fire (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

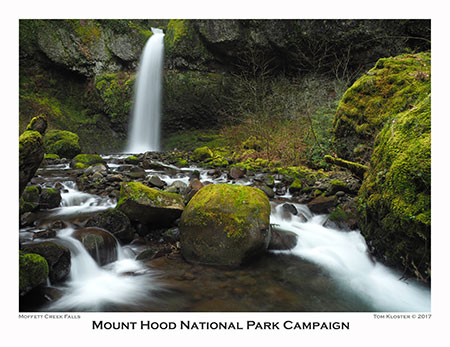

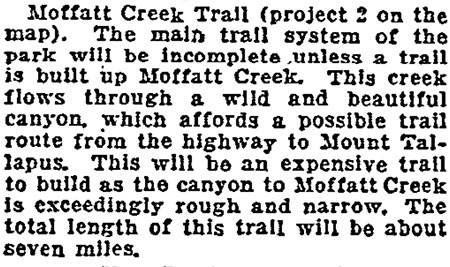

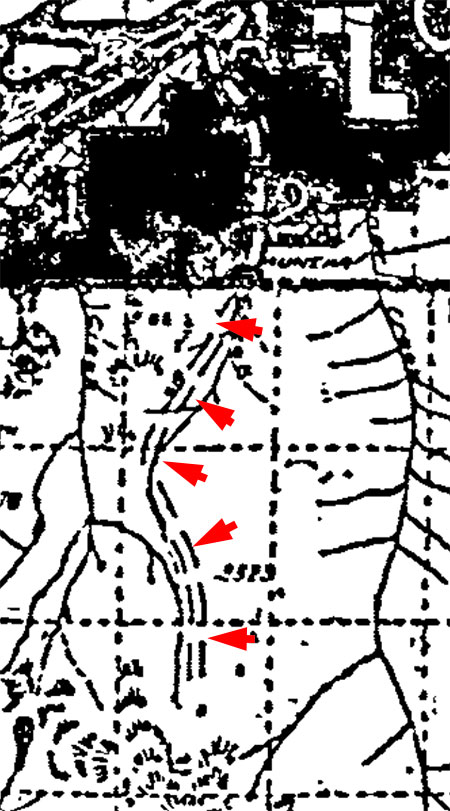

At about the time the original Columbia River Highway was built in the early 1900s, a group of Portlanders proposed a daring trail into Moffett Creek canyon, much like what was built along Eagle Creek at the time, but the project stalled. Today there are no trails into Moffett Creek canyon, though a few visit Moffett Falls each year by following the creek a mile upstream from where the stream flows into the Columbia River. A few more explorers climb farther, to beautiful Wahe Falls, but only the most intrepid explorers have rappelled down the string of 11 spectacular waterfalls hidden in the depths of Moffett Creek canyon.

Some of the big conifers in the lower canyon appear to have survived the fire, but this close-up view (below) of Moffett Falls shows that the forest around the falls was less fortunate:

Moffett Falls after the fire (State of Oregon)

Last April, I visited Moffett Falls with a friend, and was surprised by the number of fallen trees and debris in the lower canyon from the rough winter of 2016-17, but I never imagined that the entire forest would soon burn. This is Moffett Falls as it looked last spring, before the fire:

Moffett Falls in April 2017

This photo from the State of Oregon series shows the lesser-known mid-section of Moffett Creek canyon, with Wahe Falls at the bottom of the photo:

Moffett Creek canyon (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

This section of Moffett Creek canyon was heavily impacted by the fire, and most of the forest killed by the flames. The recovery here will go unnoticed by most, though the few who explored this beautiful canyon before the fire will find these images difficult to absorb.

Here’s a close-up view of Wahe Falls from the previous photo, showing that all the big conifers around the falls were killed by the fire:

Wahe Falls after the fire (State of Oregon)

Moving upstream, the burn was less devastating in the next section of Moffett Creek canyon, where towering Kwaneesum Falls is located:

Upper Moffett Creek canyon and Kwaneesum Falls (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

Kwaneesum is the tallest of Moffett’s eleven waterfalls, named by local waterfall explorer Zach Forsyth with the Chinook word meaning “forever, eternity or always.” This closer look at Kwanesum Falls shows many of the big conifers below the falls surviving the fire:

Kwaneesum Falls after the fire (State of Oregon)

An even closer look (below) at the forest below the falls reveals the complex burn patterns that result from the unusually steep topography of the Columbia River Gorge. Here, some trees were killed by the fire, while others survived. The Western red cedar on the left was singed on just one side, and may have enough green foliage to survive:

Complex burn patterns along Moffett Creek (State of Oregon)

Few have ever seen Moffett Creek and few of us were ever destined to because of its remoteness. The canyon will also recover beyond the reach of humans, as it has many times before over the centuries. For a wonderful glimpse into some of the secrets this canyon holds, and a look at the lush beauty before the fire, you can pick up Zach Forsyth’s excellent Moffett Creek book in his “Hidden Treasures” series over here.

The next photo in the series (below) shows the lower canyon of Moffett Creek and the eastern flank of popular Munra Point, a rocky spine that towers above the Bonneville area, and forms the divide between Moffett and Tanner creeks:

Munra Point and Moffett Creek (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

Munra Point is perhaps the most popular “unofficial” trail in the Gorge — or Oregon, for that matter. While it was once a lightly visited secret, the growing Portland region and advent of social media has turned this steep goat path into an actual zoo on summer weekends. The Forest Service has made no attempt to manage the user trail to Munra Point, as it’s “off the system” and in recent years it has suffered serious damage and erosion as the web of steep user paths has grown here.

This closer view (below) of the trail corridor suggests that the Eagle Creek F Fire had it out for the Munra Point trail, as the worst of the burn managed to focus on the route of this unofficial trail:

The user trail to Munra Point follows the burned ridge at center-left in this view (State of Oregon)

The burned forest and subsequent erosion on these steep slopes will make it dangerous and unsustainable for hikers to continue to flock to this trail. It’s time for the Forest Service to officially close the unofficial Munra Point trail. The slopes will take decades to recover from the fire, and maybe someday a better-designed trail could be reopened, once the forest has recovered. For now, Munra Point deserves a long rest from our collective hiking boots.

Moving east, the next photo in the series (below) shows the Bonneville Fish Hatchery, the bridges of I-84, the Union Pacific Railroad bridge and (if you look closely) the old Tanner Creek Bridge on the Historic Columbia River Highway State Trail. Just beyond is the lower section of the Tanner Creek canyon, one of the most beloved places in the Gorge:

Bonneville hatchery and Tanner Creek canyon (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

Despite being just one ridge away from the origin of the Eagle Creek Fire, the lower Tanner Creek canyon seems to have fared surprisingly well, as shown by this close-up view (below). Some of the largest, oldest trees in the Columbia River Gorge make their home here, and many seem to have survived the fire intact.

Lower Tanner Creek canyon (State of Oregon)

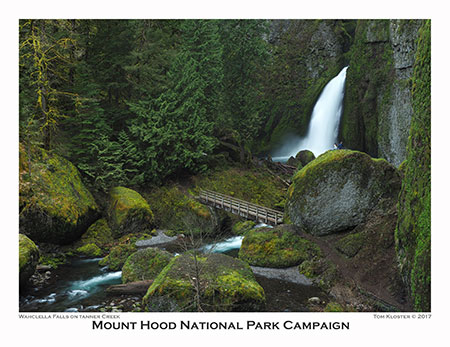

This photo in the series is taken from high above the lower Tanner Creek canyon, looking into the amphitheater that holds Wahclella Falls, one of the most visited and loved places in the Gorge:

Tanner Creek and Wahclella Falls (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

This view also shows the narrow gorge above Wahclella Falls, where little-known Swawaa and Sundance falls are located just upstream along Tanner Creek. The wide view also shows how much more severely the upper canyon burned, above the waterfalls.

In past articles, I’ve proposed extending the Tanner Creek trail to this string of upstream waterfalls, but it’s unclear if the fire will open new opportunities for trails or slow down efforts to build them. There will be pressures in both directions within our public land agencies and among Gorge advocates. My hope is that we can build new trails while the terrain is relatively open and it’s relatively easy to survey, plan and build new routes.

While the fire clearly swept through the understory of this part of Tanner Creek canyon, much of the conifer forest immediately around iconic Wahclella Falls seems to have survived the fire, as seen in this close-up from the photo above:

Wahclella Falls after the fire (State of Oregon)

This will come as relief to many, though we’ll only know the long-term fate of these survivors after they have endured a couple of summer drought cycles.

The fate of the groves of Bigleaf maple and Oregon white oak (below) that also thrived here is less certain. We’ll know in spring when deciduous trees begin leafing out.

Bigleaf maples lighting up Wahclella Falls in autumn 2012, before the fire

The next photo in the series (below) shows upper Tanner Creek canyon, with an extensive mosaic burn pattern, and many trees along the canyon floor and west canyon wall surviving. The east slope of the canyon, below Tanner Ridge and Tanner Butte, appears to have burned more severely:

Upper Tanner Creek canyon (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

This close-up (below) of an unnamed rock outcrop and talus slope on the west wall of the canyon shows another potential benefit of the fire. Among the signature habitats in the Columbia River Gorge are the many remote talus slopes that support unique species, and in particular, the Pika. These tiny relatives of rabbits live exclusively in talus, and the Gorge is home to the only known low-elevation population in the world, as Pika typically live in subalpine talus.

Cleared talus slopes above Tanner Creek (State of Oregon)

Assuming low-elevation Columbia Gorge pika living in talus slopes like these survived the fire, itself, the effect of burning off encroaching forest is a long-term benefit for these animals by preserving the open talus and promoting growth of sun-loving grasses, wildflowers and huckleberries that Pika depend on.

Pika gathering huckleberry leaves (ODFW)

Another larger species that might benefit from cleared talus and ridge tops is the mountain goat — if it is reintroduced here, or migrates from where it has been re-introduced elsewhere. A 1970s effort to bring them back to the Columbia Gorge was not successful, but perhaps now is the time to try again?

This close-up view (below) of upper Tanner Creek shows the high degree of mosaic burn on the canyon floor that will not only help the forest recover, but also allow for a healthier forest of mixed, multi-aged stands to develop over coming decades:

Mosaic burn pattern along upper Tanner Creek (State of Oregon)

The next photo in the State of Oregon series shows the impact of the Eagle Creek Fire on Tooth Rock, the legendary pinch-point for travel through the Columbia Gorge, from early railroads to modern freeways:

Tooth Rock after the fire (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

Tooth Rock is just a couple of miles from where the fire started, and one of the first places to burn, closing the highway and railroad for days. This close-up view (below) from the above photo shows a section of the Historic Columbia River Highway State Trail at Tooth Rock where erosion and landslides unleashed from the burn will be an ongoing concern until the understory recovers:

Historic Highway viaduct at Tooth Rock (State of Oregon)

If you’ve traveled through the Columbia Gorge since the fire, you have probably noticed the protective fencing above the Tooth Rock Tunnel and fresh stumps where burned trees were cut by the highway department to prevent them from falling onto the highway.

This close-up view (below) shows the larger concern, where active slides threaten the historic highway, as well as the portal to the Tooth Rock Tunnel and Union Pacific tunnels, located below the westbound I-84 viaduct:

Stacked transportation routes threatened by slides at Tooth Rock (State of Oregon)

And so the ongoing struggle to find passage around Tooth Rock continues, as the successive roads, rails, tunnels and viaducts making their way around and through the rock over the past 150 years may all share a common fate if these landslides continue to grow.

Eagle Creek: at the Heart of the Inferno

Eagle Creek forest burning as the fire began to unfold last September (US Forest Service)

The intensity of the fire damage to the forests in Oneonta, McCord and Tanner creek canyons might lead you to think the Eagle Creek canyon would have fared worse, since the fire was started here. But the State of Oregon aerial photo series shows the forest canopy in many of the most treasured spots along Eagle Creek surviving the fire, with many areas having a beneficial, mosaic burn pattern.

The mosaic pattern is immediately apparent in this opening view, looking into the canyon from above the Eagle Creek fish hatchery and I-84:

Looking into the Eagle Creek canyon (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

A closer look (below) at this view shows that much of the forest along the lower canyon near the Eagle Creek trailhead survived. The historic Eagle Creek Campground is also located in this area:

Lower Eagle Creek canyon (State of Oregon)

A still closer look (below) shows that the understory on the west (right) side of Eagle Creek in area stretch burned, while much of the conifer overstory has survived, so far:

West side of lower Eagle Creek (State of Oregon)

The next photo in the series jumps two miles upstream along Eagle Creek to Metlako Gorge, so the extent of the burn in the intervening section of the Eagle Creek Trail is still only known to Forest Service rangers who have been busy assessing trail conditions in the burn area.

This photo (below) looking south into Metlako Gorge shows more mosaic burn pattern, with an intact forest canopy in some areas and dying trees in others. Sorenson Creek Falls (on the left) and Metlako Falls spill into the gorge at the far end:

Metlako Gorge after the fire (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

A closer look at this photo shows that the understory was cleared by the fire on the slopes below the Eagle Creek Trail, located directly above the falls. The two familiar Douglas fir trees that lean over the gorge just below Metlako Falls also seem to have been killed by the fire:

Sorenson Creek Falls and Metlako Falls after the fire (State of Oregon)

This fascinating (below) photo from the series shows the former Metlako Falls viewpoint, once located on a short spur trail through a wooded ravine that led to a dizzying perch along the gorge rim. In late December 2016, a massive section of the basalt cliff fell away here, taking the viewpoint (and its cable railings!) with it and filling the gorge below with 30 feet of debris:

The 2016 Metlako Gorge landslide after the fire (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

In this earlier blog article, I covered the landslide event in detail, but the new aerial views provide a much more complete understanding of the full scope and scale of the collapse.

This closer look at the photo (below) shows the scale of the collapse, including a barn-sized chunk of solid basalt that managed to land in Eagle Creek intact. The giant, intact boulder gives a good sense of just how much of the original cliff broke away:

Close-up view of the 2016 Metlako Gorge landslide (State of Oregon)

A still closer look (below) shows the impact of the collapse on Eagle Creek, with a deep bank of rock and soil debris banked against the east wall of the gorge, and huge pile of boulders in the creek trapping a log jam of whole trees behind it:

Logjam created by the 2016 Metlako Gorge landslide (State of Oregon)

This photo from the series (below) of the newly formed Metlako Gorge cliff face helps explain why the cliff collapse happened. The waterfall cascading down the newly exposed scarp is located just upstream from where the overlook was located, and emerges from the small ravine the spur trail followed to the old overlook:

Metlako Gorge landslide scarp after the fire (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

A closer look at this new waterfall (below) shows that the entire stream actually emerges at the brink of the falls, where groundwater flowing beneath the forest surface has reached the solid basalt layer and is forced toward the cliff.

Constant hydraulic pressure and occasional freezing where this underground water source seeped into cracks in the basalt layer and the sheer weight of the vertical cliff pulling outward created the conditions for what is a fairly regular event in the Columbia River Gorge: outer layers of exposed basalt cliffs calving off as the elements pry them loose.

A new waterfall where the Metlako Falls viewpoint once was (State of Oregon)

What did Metlako Gorge look like before the landslide? It was an idyllic, widely photographed scene of exceptional beauty. This image (below) is no longer possible after the cliff collapse, but the 2017 Eagle Creek fire also destroyed some of the big trees that framed the falls. This view will only live in our photos and memories:

Metlako Falls before the viewpoint collapse — and the Eagle Creek fire

This aerial view from the series provides a more detailed look at Metlako Falls, including a rarely seen section of Eagle Creek just above the falls and the surrounding forest:

Metlako Falls after the fire (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

A closer look (below) at this photo shows that the fire completely burned away the understory around the falls, and many of the trees here are clearly struggling to survive. Soils in the rocky Columbia Gorge canyons are thin and competition is fierce among big trees during summer droughts, so we won’t really know how trees with this degree of fire damage will fare for another year or two.

Metlako Falls after the fire (State of Oregon)

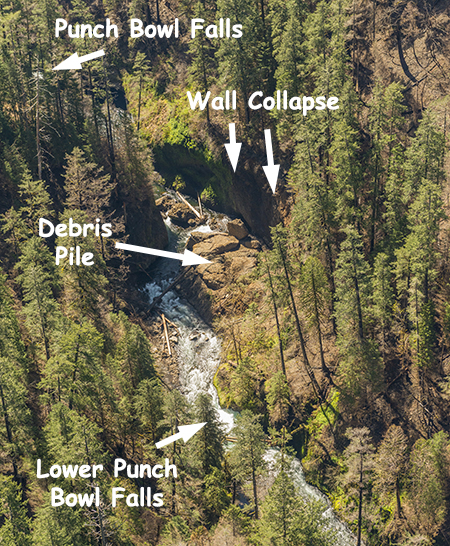

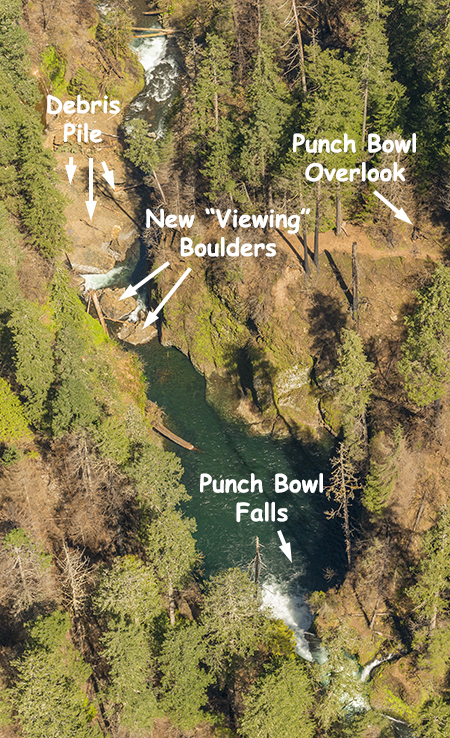

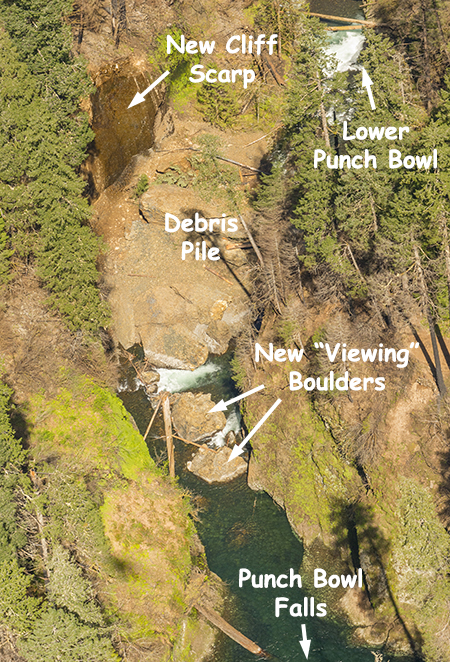

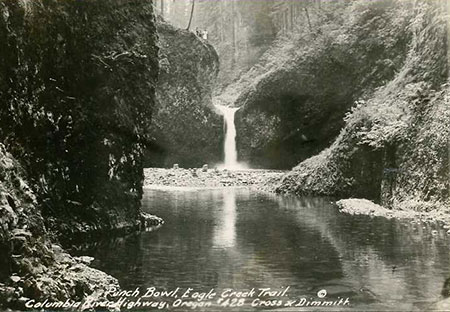

As I worked my way through the hundreds of photos in the State of Oregon series, I expected to find a shot of Punch Bowl Falls similar to the previous view of Metlako Falls. After all, Punch Bowl is easily among most photographed spots in the Columbia Gorge (and Oregon), second only to Multnomah Falls. But after my first pass through the set, I was disappointed not to find a good view of the Punch Bowl, of all places!

However, I later came across the following image in a group of several that were more difficult to identify, and noticed the undercut cliff wall tucked among the trees in the lower left edge of the photo:

Is that Punch Bowl Falls down there..? (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

Looking more closely (below) at this part of the photo reveals it to be the “weeping wall” that towers above the lower Punch Bowl amphitheater, across from the cobble beach that fills with hundreds of hikers and swimmers on summer weekends. Then I noticed a bare spot that marks the “jumping” spot on the high cliff that hangs above the east side of Punch Bowl Falls — and the trail overlook, in the trees high above the falls:

…that’s a downstream view of Punch Bowl Falls! (State of Oregon)

The good news from this photo is that several stands of big conifers immediately around Punch Bowl Falls not only survived the fire, but look to have completely dodged the flames. That would be good news, as these trees may now live to grow for another century or two, helping the surrounding burn recover and passing along their survivor genes in the process.

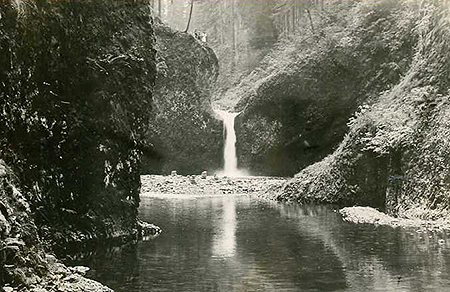

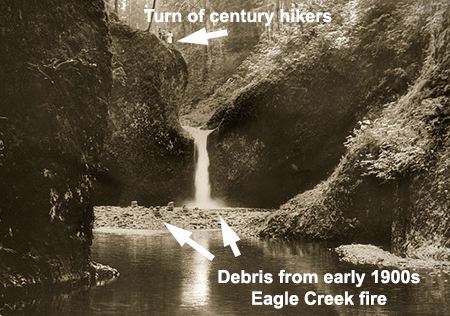

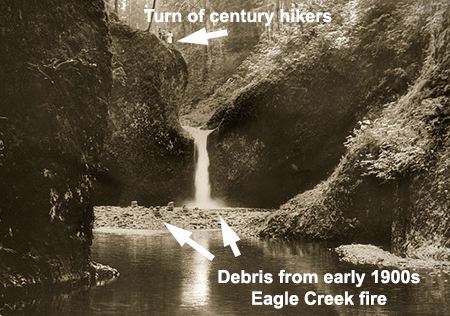

Many of the big trees around Punch Bowl Falls have survived at least one other major fire, as much of the Eagle Creek canyon burned in a fire around the turn of the 20th Century. This early 1900s view (below) shows the aftermath of that fire, with large gravel bars filling the Punch Bowl, itself. This material was released by erosion that resulted from that earlier fire, and in coming decades, we are likely to see new gravel bars like this appear in Eagle Creek, once again:

Early 1900s view of Punch Bowl Falls

Most hikers on the Eagle Creek Trail know Tish Creek from its tall — and recently replaced — footbridge. But a few intrepid hikers know that a beautiful waterfall on Tish Creek is located upstream from the trail, reachable by a rough off-trail bushwhack. This little-known spot also seems to have dodged the worst of the fire, as seen in this view aerial view from the series:

Tish Creek Falls after the fire (State of Oregon)

Moving upstream from Punch Bowl Falls, the photo from the series shows Loowit Gorge, just downstream from Loowit Falls and High Bridge:

Loowit Gorge after the fire (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

Eagle Creek was clearly a barrier for the fire in this area, with the west (right) slopes near Loowit Creek completely burned, while the forest canopy on the east slope (where the Eagle Creek Trail is located) seems to have mostly survived, but with burned trunks to show for it.

This aerial view from the series shows Loowit Falls (at the bottom, where it joins Eagle Creek) and little-known Upper Loowit Falls in the distance:

Loowit and Upper Loowit Falls after the fire (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

A closer look (below) at this view of Loowit Falls shows a forest that was largely killed by the fire, as even the trees with a few surviving limbs in their crowns are unlikely to survive the stress of losing so much of their canopy:

Loowit Falls after the fire (State of Oregon)

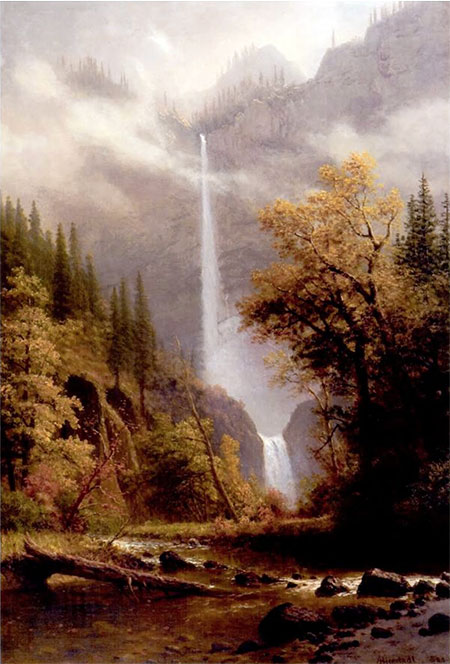

What did Loowit Falls look like before the fire? It was among the most graceful and photographed in the Columbia Gorge, drifting down a moss-covered basalt wall into a perfect bowl carved into solid rock over the millennia:

Loowit Falls before the burn, surrounded by big conifers (State of Oregon)

Upper Loowit Falls fared worse (below), with the entire forest killed by the fire. In recent years, the word has gotten out on the relatively easy off-trail route to this falls, so like Middle Oneonta Falls, this might be a good candidate for formalizing a spur trail. This could be done as part of restoring the overall trail system at Eagle Creek, when trail planners can see the terrain as never before, and have the opportunity to provide more hiking options in this popular area.

Upper Loowit Falls after the fire (State of Oregon)

This photo from the series looks downstream along a section of Eagle Creek above High Bridge:

Eagle Creek above High Bridge after the fire (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

The burn is extensive here, though a few stands of forest canopy seem to have survived. A close look at the tributary falls in the upper left corner of this view shows Benson Falls, another beautiful, lesser-known waterfall that only a few have visited:

Benson Falls after the fire (State of Oregon)

Graceful Benson Falls can be reached by scrambling up a side canyon from near High Bridge. This similar view from another photo in the series shows the falls more clearly, and while the burn cleared much of the understory here, many of the big conifers near the falls appear to have survived:

Benson Falls after the fire (State of Oregon)

Benson Falls could be another candidate for a short spur trail as part of restoring the Eagle Creek Trail in the burn area and providing new trail opportunities.

Moving upstream, the next photo in the State of Oregon series shows a section of Eagle Creek located below Skoonichuk Falls, the next in the chain of waterfalls along the Eagle Creek Trail:

Eagle Creek and Skoonichuk Falls after the fire (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

Much of the forest in this section of Eagle Creek canyon was completely killed by the fire, though a few conifers survived immediately around Skoonichuk Falls, as seen in this close-up view:

Skoonichuk Falls after the fire (State of Oregon)

Unfortunately, the aerial photo series does not include a view of Grand Union Falls and Tunnel Falls (on the East Fork), the next two major waterfalls along the Eagle Creek Trail, so only the Forest Service rangers know the extent of the fire impact there. But the photo series does include this view of Twister Falls, located on the main fork of Eagle Creek, just up the trail from Tunnel Falls:

Twister Falls after the fire (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

Eagle Creek formed another firebreak here, though in the opposite direction from what previous photos showed at Loowit Gorge. Here, the forest canopy on the west (right) side of the canyon appears to have mostly survived, while the east side canopy was mostly killed by the fire.

This close-up view (below) of the photo shows the infamous “Vertigo Mile” section of the Eagle Creek Trail, where the exposed route curves around a dizzying cliff above Twister Falls. The fire damage here is readily apparent on the slopes above the trail, with only a few conifers hanging on to some of their foliage:

Twister Falls and the Vertigo Mile after the fire (State of Oregon)

These trees are unlikely to weather summer drought stress in coming years as they attempt to survive with only portion of their crowns intact. As will be the case throughout the burn, debris from heavily burned slopes like this will continue to slide onto adjacent trails until the forest understory has returned to stabilize the soil. This will likely play out for several years.

The groves of big conifers at the base of Twister Falls (below) seem to have fared much better, possibly untouched by the fire:

These big trees below Twister Falls survived the fire (State of Oregon)

Like the big trees that survived by Punch Bowl Falls, these giants will help the surrounding burn recover by helping to reseed burned slopes and providing shade to help keep Eagle Creek cool in summer and early fall.

This view from the brink of Twister Falls (below) from before the fire shows the narrow slot that holds this tall waterfall. In coming years, watch for logjams to form in narrow spots like this along Eagle Creek:

Twister Falls before the fire

This photo in the series shows Sevenmile Falls, the last in the string of major waterfalls along the Eagle Creek Trail:

Sevenmile Falls after the fire (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

The understory burned off in this section of forest, but the conifer overstory seems to have survived, mostly intact. This close-up view from the photo shows a more impacted section of forest where the Eagle Creek Trail passes Sevenmile Falls:

Sevenmile Falls after the fire (State of Oregon)

This photo from the series provides a view from high above the upper Eagle Creek canyon, looking downstream (north) toward the Columbia River, and gives a sense of how the forests in the upper canyon fared:

Upper Eagle Creek canyon after the fire (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

While forests along many of the ridge tops were completely killed by the fire, many of the lower slopes in this photo (below) show a beneficial mosaic burn, with wide bands of surviving forest canopy:

Mosaic burn pattern in the upper Eagle Creek canyon (State of Oregon)

The condition of trails in this part of the Eagle Creek network is unknown, as the Eagle Creek fire merged with the earlier Indian Creek fire in this area. The Indian Creek fire started weeks before the Eagle Creek fire, but spread less aggressively, mostly burning in relatively high elevation areas above the canyon floor.

Herman Creek and Shellrock Mountain

The State of Oregon photo series doesn’t provide much detail on the Herman Creek canyon, though the fire clearly burned significant portions of Nick Eaton Ridge (seen below, forming the east side of the canyon on the left in the photo). This photo was taken from directly above the Port of Cascade Locks, looking south:

Herman Creek canyon after the fire (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

From this limited view, the pattern seems similar to Eagle Creek: killed forests along ridge tops, mosaic burn patterns closer to the canyon floor and some of the largest conifers surviving along Herman Creek (below).

Mosaic burn pattern at Herman Creek (State of Oregon)

The final image in this set focuses on Shellrock Mountain, the eastern extent of the State of Oregon photo survey (below):

Summit Creek and Shellrock Mountain after the fire (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

A closer look at the lower left corner of the photo (below) shows little-known Camp Benson Falls, the lower of two significant waterfalls on Summit Creek, and the ongoing construction of the latest phase of the Historic Columbia River Highway State Trail:

Summit Creek and Camp Benson Falls (State of Oregon)

Most of the burn here is also in a mosaic pattern, including along the steep talus slopes of Shellrock Mountain (below). Switchbacks from an old trail leading to the summit show in this view, as well:

Shellrock Mountain forests after the fire (State of Oregon)

The amazing photo survey ends here, roughly coinciding with the eastern extent of the Eagle Creek Fire. Though the photos were focused on assessing potential impacts of burned slopes on highways and other infrastructure in the Gorge, they also serve as an invaluable snapshot of conditions as they existed immediately after the fire. These images will give future land managers and researchers a highly detailed benchmark for tracking the recovery of the Gorge ecosystem over coming decades.

While simply restoring the historic trail network will be a big job, the reality of growing demand in our region for new trails and experiences in the Gorge didn’t go away with the fire. These photos also provide a unique opportunity for today’s State Parks and Forest Service planners to consider new trails and trail realignments while the terrain is easy to survey and trail construction more straightforward than when the understory is intact.

The fire has created a once in a century opportunity to rethink the trails in the Gorge with our rapidly growing population in mind, and is an opportunity that should not be missed. It also provides an opportunity to link the responsible expansion of recreation opportunities to the forest recovery, itself, allowing hikers to watch and learn as a new forest grows here.

After the Fire: the Verdict

Smoky skies in the Gorge during the 2017 Eagle Creek Fire

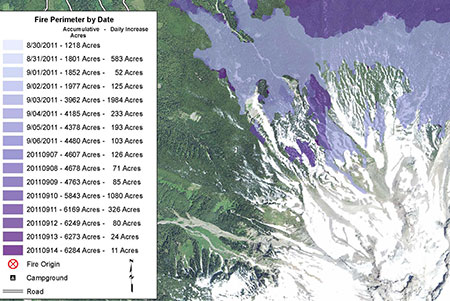

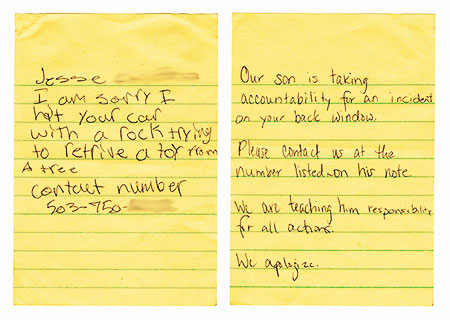

Those who love the Gorge already know this unfortunately sequence of events: the Eagle Creek Fire began on September 2, 2017, when a Vancouver teenager tossed illegal fireworks into the canyon from cliffs along the Eagle Creek trail. The fire quickly exploded into an inferno, burning more than 48,000 acres along the Oregon side of the Columbia River Gorge, and briefly igniting a small fire on the Washington side when embers floated over to the slopes of Aldrich Mountain.

This month, a Hood River County judge sentenced the teen to five years of probation and 1,920 hours (48 weeks) of community service with the U.S. Forest Service. That’s more volunteer time that many Americans contribute over a lifetime. Much of that work will be in the form of restoring and rebuilding trails damaged by the fire, no doubt, and hopefully this mandated service will inspire the unnamed teen to dedicate his life to protecting our public lands after this tragedy.

The public reaction to the sentence was swift: many felt it was too lenient, given the scope and devastation of the fire. Others felt it fair and forgiving, as it gives the teen a chance to potentially direct his life toward stewardship and protecting the Gorge. Here is the statement the young man made to the court as part of sentencing:

Letter of apology from the teen who started the Eagle Creek Fire

[click here for a more readable version]

I fall into the second category in my own reaction, and don’t see a reason to destroy a young life because of a mistake that went horribly wrong. Most of us made similarly stupid decisions in our teens, and were simply fortunate enough not to have had consequences of this scale to answer to.

I also see this sequence of events as a metaphor that all who love the Gorge can learn from: today’s kids are increasingly isolated from nature and spending time on our public lands. Learning to understand, appreciate and respect nature is something that all kids should experience, and might have prevented the Eagle Creek Fire, too.

The teen who started the Eagle Creek Fire will spend nearly a year in his young life working to help with the recovery effort as part of his sentence and will surely learn these lessons. But what if all kids in our growing region simply spent a few hours working on a trail or helping to restore the burn in some other way? How would that change the way in which future generations care for the Gorge? How could we all help to bring out youth closer to nature as we work to restore the Gorge?

Epilogue: Learning to Embrace the Burn

Bleached snags from the 1991 Multnomah Falls fire rising from a sea of young conifers in 2004

Reactions to the first in this two-part article ranged from sadness and anger over places lost to the fire to a degree of hope and guarded optimism about the opportunity to rethink how we manage the Gorge in the future.

While the full impact of the Eagle Creek Fire is still being assessed, the best option moving forward is to embrace the reality of the burn as an opportunity to learn, grow and pitch in. That’s something we can all do, including supporting organizations like Friends of the Gorge and Trailkeepers of Oregon (TKO) who will be at the forefront of bringing volunteers to the major job of restoration.

So far, the public response has been overwhelming, with several TKO trail events filling up almost immediately this year, and long waiting lists forming for future events. That’s encouraging! Let’s hope it continues, as the recovery will take many years.

Many will continue to grieve the magnificent forests and idyllic landscapes lost to the fire, too. That’s a very human response to losing a place that is home to so many of us. But it’s also true that the recovery has already begun, and that each year in the recovery process will bring new opportunities to learn and appreciate how the Gorge ecosystem has recovered countless times from fire over the millennia.

Young conifers growing among the snags from the 1991 Multnomah Falls fire in 2004

For those of us at (or past) the middle of our lives, our memories of what was will have to fill some of the void we feel. But younger visitors to the Gorge will see whole new forests grow among the bleached snags that will soon mark much of the burn area, and the very youngest visitors will live to see tall forests grow here, again.

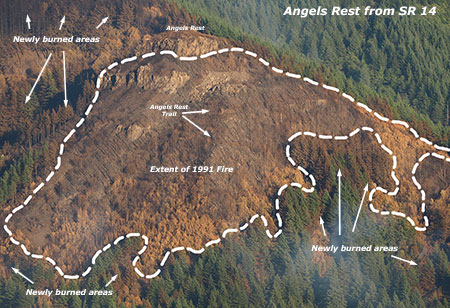

2004 view of young trees rapidly filling in the 1991 burn area above Angels Rest

What will the recovery look like? The 1991 Multnomah Falls Fire gives us the best glimpse into what to expect as the Eagle Creek recovery unfolds. For those who were around in 1991, the Multnomah Falls Fire swept from the falls west to Angels Rest, scorching much of the Gorge wall along the way. I’ve included a few photos of the burn area taken in 2004, just 13 years after the fire.

At that point in the recovery, trees killed by the 1991 fire still dominated the landscape, but a young forest seemed to be exploding from the burn area, with conifers already 10-15 feet tall and growing quickly. Today, some of these trees are twice that tall, and on the way to becoming a mature forest canopy.

2004 view of the 1991 Multnomah Falls burn, with young trees rapidly overtaking the ghost forest of burned trees

It shouldn’t be a surprise to discover that the Gorge ecosystem can recover quickly and without our help. But with thousands of people living in the Gorge and millions visiting each year, we will also need to learn how to accept fire as part of the forest cycle if we hope to avoid catastrophic burns like the Eagle Creek Fire in the future.

What will that take? One essential tool will be prescribed burns. These are purposely set fires designed to burn a relatively small, controlled area with a relatively cool fire that most of the forest canopy can survive. The goal of a prescribed burn is a mosaic pattern like those found in parts of the Eagle Creek Burn where the fire intensity was less and allowed most trees to survive.

2015 prescribed burn in Yosemite National Park (National Park Service)

Prescribed burns are typically set in late fall, when humidity is high and the rainy season is near and can be counted on to completely extinguish the fire. The Eagle Creek burn occurred in late summer when humidity was low, the forests very dry after two months of drought and the first substantial fall rains were weeks away. The famous Gorge winds only added to the volatility. These conditions combined to allow the fire to burn hot and spread for weeks.

Prescribed burns are now an accepted forest practice, and increasingly used by the Forest Service and National Park Service to reverse the harm done by a century of fire suppression. But preventing future fires on the scale of the Eagle Creek Fire will also require all of us to accept limits on how we use the Gorge. This may be more difficult to accept than prescribed burning, especially given the patchwork of public agencies responsible for managing the Gorge.

What sorts of limits are needed? Restored trails in the burn area will be vulnerable for years to come, and subject to more damage if the same level of foot traffic experienced before the fire is allowed to return. The public agencies that manage the Gorge will need to define and identify reasonable carrying capacities for the most popular trails, and enforce access limits with trail-specific permits, parking management and by offering new trail options for a growing region.

Our children’s grandchildren will experience the Eagle Creek burn like this: scattered ghost stumps from today’s burned trees among a green rainforest of 100-year old trees

Seasonal limits may be required, too. The Gorge was a tinderbox waiting to burn last September when the Vancouver teen tossed fireworks into the Eagle Creek canyon, starting the fire. But it could have easily started from an untended campfire or careless smoker, too.

In the future, seasonal trail limits and temporary closures should also be considered when fire conditions in the Gorge are especially dangerous. This could not only help prevent overly destructive burns in the forests that still remain, but also acknowledges that thousands of Gorge residents and their homes were also threatened by the fire. Their safety should be a core consideration in deciding when to close Gorge trails because of fire risk.

Changes to current management practices will be hard to bring about with a reluctant public, but the Eagle Creek Fire might have given us the perfect moment to educate ourselves on the need to change our ways and think about how our impact on the Gorge will play out for future generations. While much was lost in the fire, we’ve also been given a unique opportunity to change course for the better. I’m optimistic that we will!

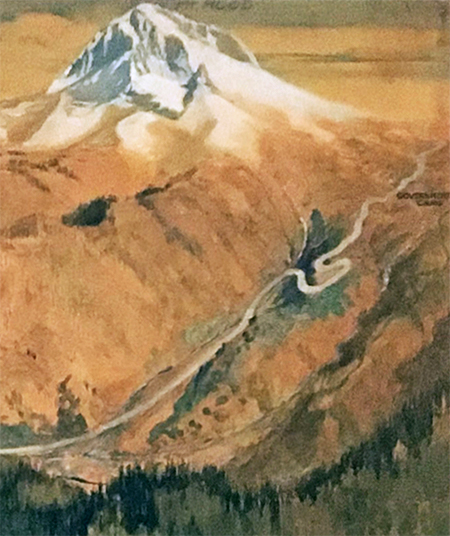

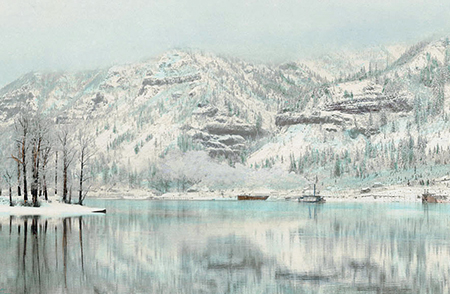

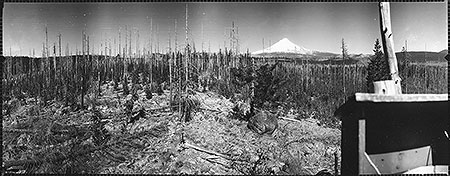

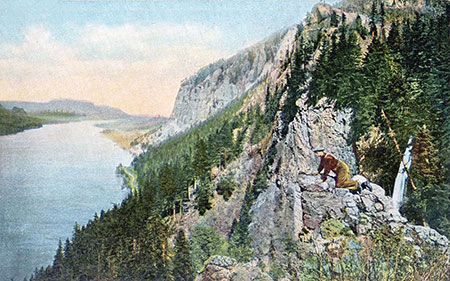

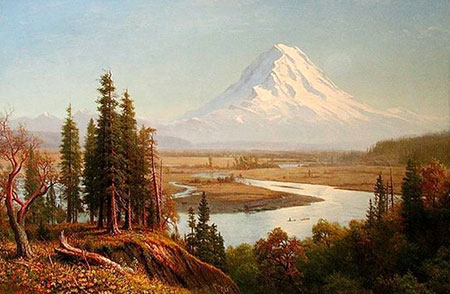

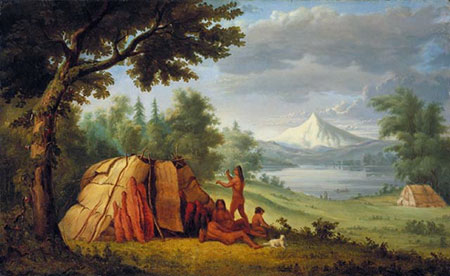

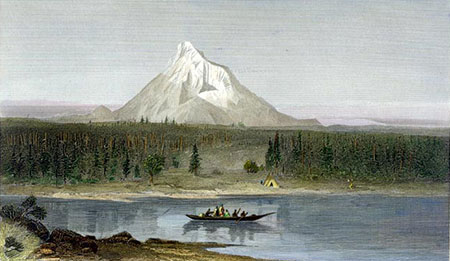

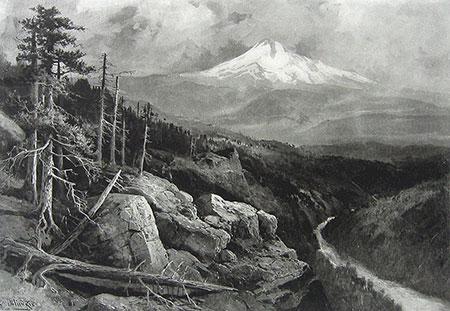

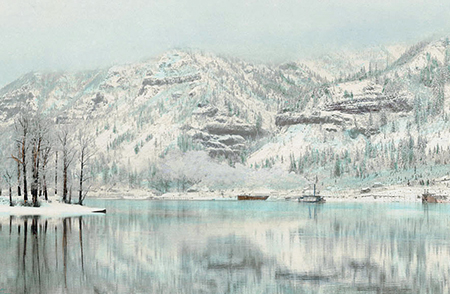

Back to the future: the Gorge was recovering from an earlier fire in this 1903 view (WyEast Blog)

[click here for a large image]

I chose the above, hand-colored photo to close this two-part article, as it provides needed perspective of our place in the broader cycle of life in the Columbia Gorge. This Kiser Brothers image was taken in 1903 from a spot just downstream from Beacon Rock, on the Washington side of the river. Across the still, reflective Columbia, the cliffs marking McCord Creek canyon can be seen, with the snow-covered slopes of Nesmith Ridge and Wauneka Point rising above.

In 1903, the Oregon side of the Gorge was just beginning to recover from an extensive fire that swept a good portion of what we now know as the Eagle Creek Burn. Past is prologue, and this is what the Gorge will look like in our immediate future, as another burn cycle unfolds.

While it’s very different scene than the green forests we have enjoyed, it’s also undeniably beautiful in a rugged, wild way. The fire is part of an essential cycle, and more importantly, an opportunity for all of us to rethink how we care for our Gorge.

I’ve also included a link to a large version of the Kiser Brothers photo, and encourage you to print a copy to hang on a bulletin board or your refrigerator as part of learning to embrace the Eagle Creek burn. This snapshot from the distant past has helped me begin to embrace the new reality of the Gorge, and I hope will help you, too.

Thanks for reading!

________________

Author’s note about the photos: a friend of the blog pointed me to the amazing cache of photos featured in this two-part article, and while you could probably acquire them from the State of Oregon, I would encourage you to let our public agency staff focus their time on the Gorge recovery, not chasing down photo requests.

With this in mind, I’ve posting the very best of the photos here, and have included links to very large images for those looking to use or share them. These photos should be credited to “State of Oregon” where noted in this article, not this blog. They are in the public domain.

________________