2022 brought new life for our 80-year-old house in North Portland!

Why, I haven’t posted an article since the end of May! Where have I been? Painting, scraping, nailing… repeat! For 30 years we have lived in a World War II-era tract house built above the North Portland shipyards back in 1944, and this year we celebrated three decades of living here by adding some much-needed space on our second floor.

Like so many workers in the COVID era, the pandemic converted me to full-time teleworker overnight, so the new space on the second floor is a new home office where I’m spending (too much) time in Zoom meetings by day and working on the house at night.

Lath from our old plaster-and-lath walls cleaned and bundled for reuse by the deconstruction crew

If you follow the photo sequence (opening image), you might note that our house was without a roof during the month of April this year – a month when Portland set the all-time record for the wettest April ever. It rained every single day! The roof had been scheduled to be installed the first week of that month, and we finally got it tacked on during the first dry stretch in early May, after 6 weeks under a leaky, whole-house tarp. The frosting (quite literally) during this saga was a freak snowstorm in mid-April (again, climate change at work) that nearly destroyed the tarp. It was like camping in our own upstairs!

My role in the project has to install trim and window casings throughout and complete all of the interior painting – work I enjoy, but also really time-consuming. Thus, the unintended “sabbatical” from my blogging. With this article, I’m happy to be putting the paintbrush aside (for a moment) and getting back to writing a few articles about all things WyEast. If working on the house left precious little time for anything else except my day job, the monotony of painting and trimming gave me time to dream up lots of new topics to write about here – so, much more to come!

Eighty-six years of very slow Douglas fir growth created this perfectly straight trim board, first installed in 1944

This article stems direction from the trim work. Whenever possible with the remodel, I recycled old trim, doors and casings from the original 1944 construction, as it is mostly made from dense, incredibly solid old-growth wood. Most lumber cut in the Pacific Northwest in the 1940s was still from centuries-old trees. This piece of 4” baseboard trim (above) was typical – it has 86 growth rings! Modern wood trim of this dimension might have ten rings, and it’s finger-jointed, engineered wood made up of foot-long sections glued together, not cut in a single plank, straight from a tree.

This was on my mind while taking a much-needed day off from nailing and painting trim a few weeks ago when I came across this fallen giant (below) along Elk Creek, near Lolo Pass. It’ an old growth Douglas fir that survived in an island of ancient forest that was passed over by the logging heyday of decades past, when much of the north side of Mount Hood was clearcut.

That’s a big log! This Douglas fir giant fell along Elk Creek in the Lolo Pass area last winter, temporarily blocking Lolo Pass Road

How big is it? Just over 4 feet in diameter – very large for a forest located just below timberline on Mount Hood

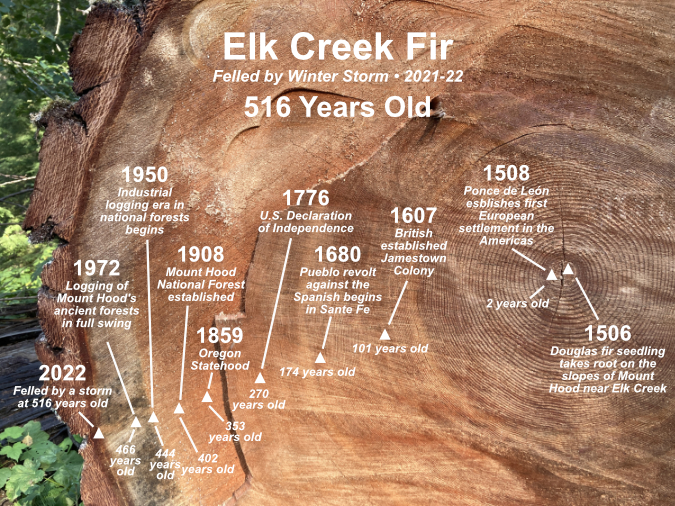

I’d always admired this old stand of trees, so I stopped to measure the fallen giant – four feet in diameter. It was not even close to the largest trees I’ve come across in Oregon’s remaining old growth forests, but then I began to count the growth rings, and stopped at two hundred when I was less than halfway toward the center of the tree! Surprised at its age, I took several photos so I could count the rings more definitively at home with the aid of computer monitor. Upon later inspection of the photos, this ancient Douglas fir turned out to be 516 years old when it was finally tipped by a storm last winter!

All around this downed giant are dozens of equally ancient Western hemlock, Western redcedar and Douglas fir growing in a spectacular, species-diverse stand that I had passed through scores of times over the years. I’d always appreciated these big old trees, but I had no idea just how long they had been growing here. How lucky we are that they have survived multiple waves of logging over the past 150 years!

These giants – Douglas fir, Noble fir and Western hemlock – are the surviving neighbors of the big tree that came down along Elk Creek last winter

Then I thought about the 86 growth rings on that old piece of base trim I’d been working with. It occurred to me that it had likely been milled from just such a tree, and was likely hundreds of years old, just as much of the wood in my 1944 house is. In the 1940s logging was still mostly focused on old growth forests, with trees that were centuries old, and the mistaken belief that it would all grow back and we would never run out of big trees.

What struck me about this 500-year-old giant is how casually it had been sawed out of the road, as like any other blowdown that got in the way. We’re still learning to appreciate these irreplaceable monarchs as more than just the board feet of lumber or sticks of firewood they can be converted into. So, to honor this ancient Douglas fir I attached a few human milestones from our frail, checkered history to its long, peaceful timeline, as told in 516 annual growth rings (below).

500 years covers a lot of recent human history. This big old fir took root as a seedling a couple years before the first Spanish settlements appeared in North America in 1508 A.D.

[click here for a large version of this graphic]

Thinking of pre-1960s homes as “old-growth homes” was a bit of a revelation for me, though it makes sense. While private lands had been heavily logged for a half-century or more at that point, second-growth forests still weren’t being logged in a significant way until well into the 1950s. Logging on public land also went into full swing in the late 1940s, flooding the market with a new supply of old-growth logs cut from mountainsides that had never been logged before.

That’s why I was pleased to learn that a big, old Portland home just a few blocks down the street from mine was being carefully deconstructed this summer, and the materials set aside for reuse. When I took at closer look at the notice posted in front of the home, I learned this was no whim of the developer – a few years ago, houses like this were routinely razed, and the debris sent to the landfill in Arlington. Now, the City of Portland now requires homes built before 1940 to be deconstructed and the materials made available for reuse.

What it looks like to un-build a house, one floor at a time – this home will be replaced with multiple dwellings in growing Portland

Behind the disappearing old home, salvaged wood and bricks are stacked in neat piles, waiting to be transported to the Rebuilding Center, a recycled building materials nonprofit working in partnership with the City of Portland in this effort. There, old reclaimed lumber and other construction materials can be reused by builders in older homes where it matches the varying lumber dimensions that were common before modern standards were applied.

Salvaged wood is organized by dimension on site and prepared for reuse at the Rebuilding Center

While it was great to reuse my old wood trim, fact is that original, old growth wood is increasingly an artifact from an era that will never repeat. Yet, wood-frame homes aren’t going away, either. Instead, they are increasingly being built with engineered wood products that are stronger, more stable and use wood cut from fast-growing, farmed tree plantations, not public lands.

Many of the new structural beams in our remodeled home were produced this way, to exacting dimensions that would be impossible with conventional cut lumber. All around Portland multi-story buildings are also being constructed with engineered cross-laminated timber beams and panels that replace steel and concrete.

This new six-floor office building on Portland’s east side streetcar loop is a wood structure, constructed entirely with cross-laminated timbers and panels, one of several new mid-rise buildings proving the value of this new material

This new industry of manufacturing cross-laminated materials (also called “mass timber”) is growing in Oregon, and has the benefit of using very small trees that can be harvested from commercial farms or – importantly – from plantation thinning on our public lands. In this way, there’s a tremendous potential for this new industry to restore rural economies around Oregon that were left behind when old growth logging faded in the 1980s and 90s. You can read more here about this emerging opportunity.

Big trees left behind during the logging heyday of the 1960s, 70s and 80s on Mount Hood’s north side now tower over the crowded plantations that cover old clearcuts. Many of these giants are hundreds of years old. Now that technology has created modern wood products that are superior to traditional lumber, will we allow these recovering forests to grow old, once again?

I like this glimpse into the future. It’s one that could allow our magnificent mountain forests to finally recover, without the future threat of commercial logging of large trees, while also providing the materials needed to house future generations of Oregonians.

This end result of having better, stronger building materials while also restoring our public forests is encouraging. If we do manage this transition, future generations will surely thank us, too.

_______________________________

Tom Kloster | October 2022