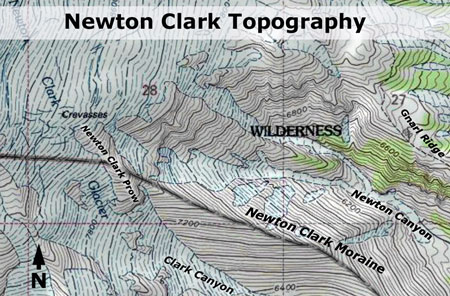

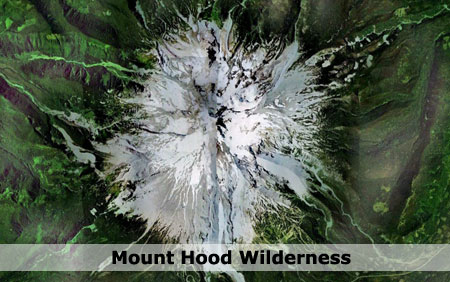

Tucked on the remote east shoulder of Mount Hood is the Newton Clark Moraine, the largest glacial formation on the mountain, and one of its most prominent features. Yet this huge, snaking ridge remains one of Mount Hood’s least known and most mysterious landmarks.

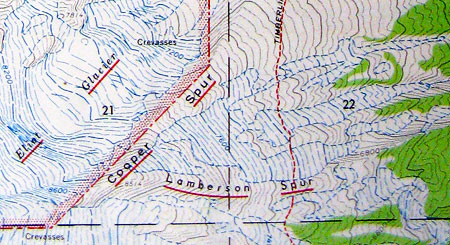

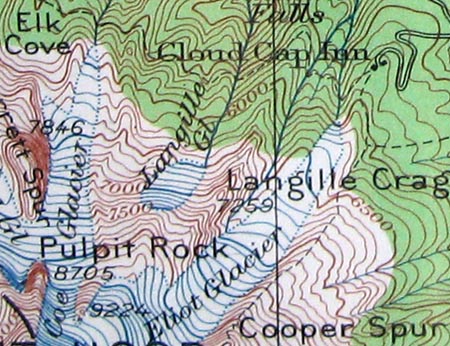

At over three miles in length, and rising as much as a thousand feet above the glacial torrents that flow along both flanks, the Newton Clark Moraine easily dwarfs the more famous moraines along the nearby Eliot Glacier.

How big is it? The Newton Clark Moraine contains roughly 600 million cubic yards of debris, ranging from fine gravels and glacial till to house-sized boulders. This translates to 950 million tons of material, which in human terms, means it would take 73 million dump truck loads to haul it away.

Backcountry skiers often call the moraine “Pea Gravel Ridge”, which is a poor choice of words, as pea gravel is something you would expect in tumbled river rock. The Newton Clark Moraine is just the opposite: a jumble of relatively young volcanic debris, some of it located where it fell in Mount Hood’s eruptive past, some of it moved here by the colossal advance of the Newton Clark Glacier during the last ice age.

As a result, the rocks making up the moraine are sharp and raw, not rounded, and the debris is largely unsorted. Giant boulders perch precariously atop loose rubble, making the moraine one of the most unstable places on the mountain.

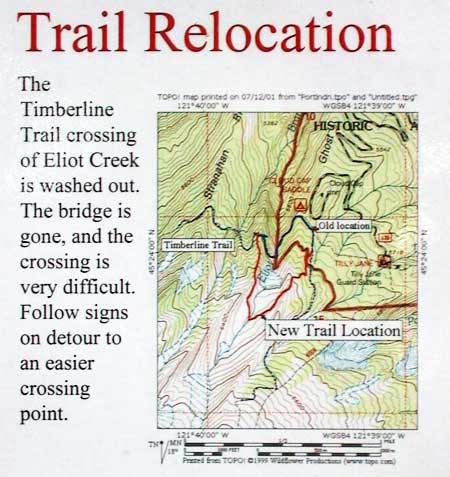

In recent years, erosion on Mount Hood has been accelerating with climate change. Sections of the Newton Clark Moraine are regularly collapsing into Newton and Clark creeks, creating massive debris flows that have repeatedly washed out Highway 35, below.

Today, an ambitious Federal Highway Administration project is underway to rebuild and — supposedly — prevent future washouts on Highway 35 at Newton Creek and the White River. But given those 73 million dump truck loads of debris located upstream on Newton Creek, it’s likely that nature has different plans for the area as climate change continues to destabilize the landscape.

Something a Little Different

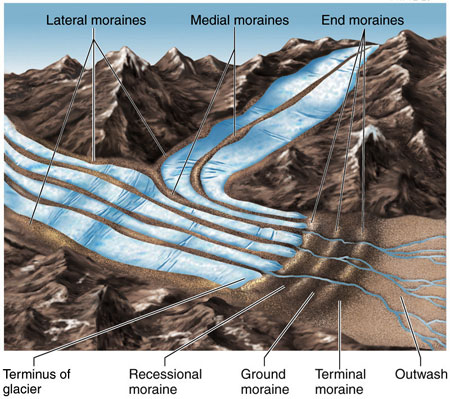

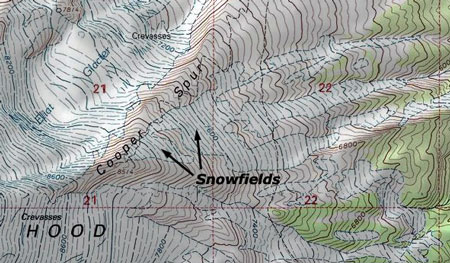

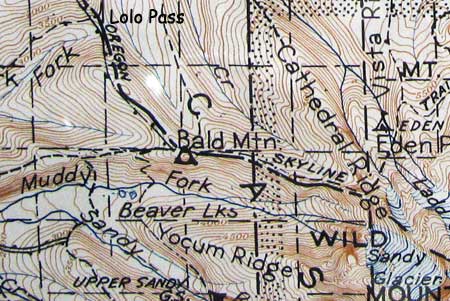

Most glacial moraines on Mount Hood are lateral moraines, formed along the flanks of glaciers, or terminal moraines formed at the end of a glacier. The Newton Clark Moraine is different: it is a medial moraine, meaning that it formed between two rivers of ice.

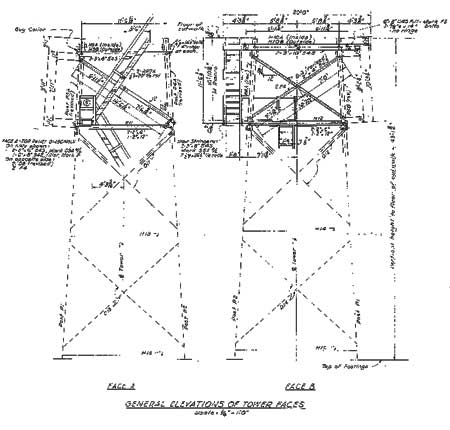

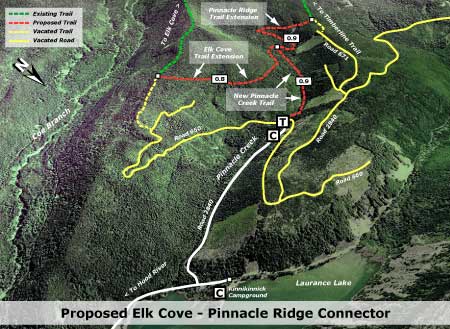

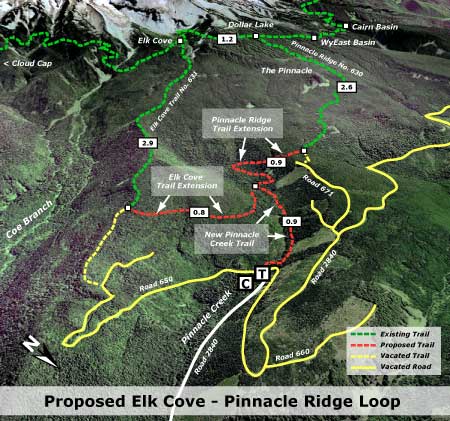

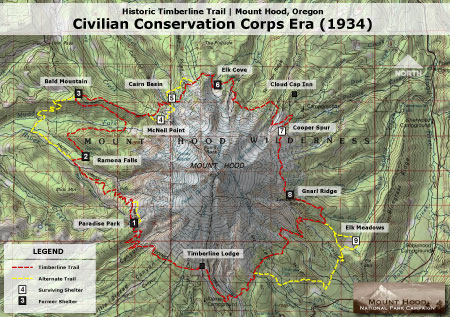

As shown in this schematic (above), medial moraines are more common in places like Alaska or Chile, where much larger glaciers flow for miles, like rivers. When these glaciers merge, a medial moraine is often created, marked by the characteristic stripe of rock that traces the border between the combined streams of ice.

At the surface of a glacier, only the top of a medial moraine is visible. Only upon a glacier retreating can the full size of a medial moraine be appreciated. In this way, the height of the Newton Clark Moraine is a reasonable estimate of the height (or depth) of the ancestral Newton Clark Glacier during the most recent ice age advance — the crest of the moraine approximates the depth of the former glacier.

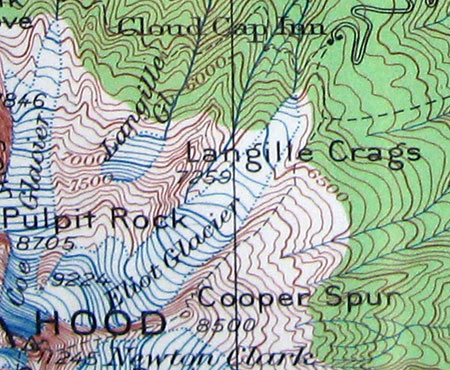

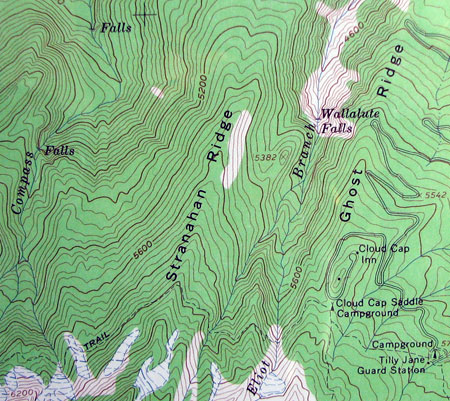

The Newton Clark Moraine is even more unique in that the two bodies of ice that formed the moraine flowed from the same glacier. Like the modern Newton Clark Glacier, the much larger ice age ancestor also began as a single, wide body of ice on Mount Hood’s east flank, but then split as it flowed around the massive rocky prow that now marks the terminus to the glacier.

The outcrop is typical of the stratovolcanoes that make up the high peaks of the Cascades. Stratovolcanoes are formed like a layer cake, with alternating flows of tough, erosion-resistant magma and loose ash and debris deposits. The Newton Clark Prow is a hard layer of magma in the “cake” that is Mount Hood, with looser layers of volcanic ash and debris piled above and below.

In fact, without this broad rib of volcanic rock to shore up its eastern side, the very summit of Mount Hood might well have been further eroded during the series of glacial advances that have excavated the peak.

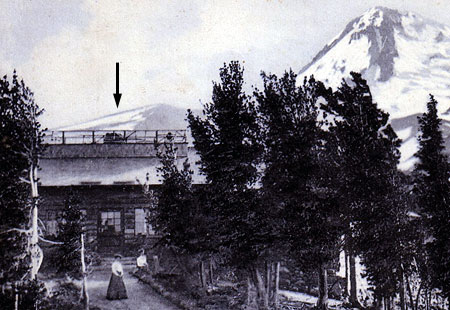

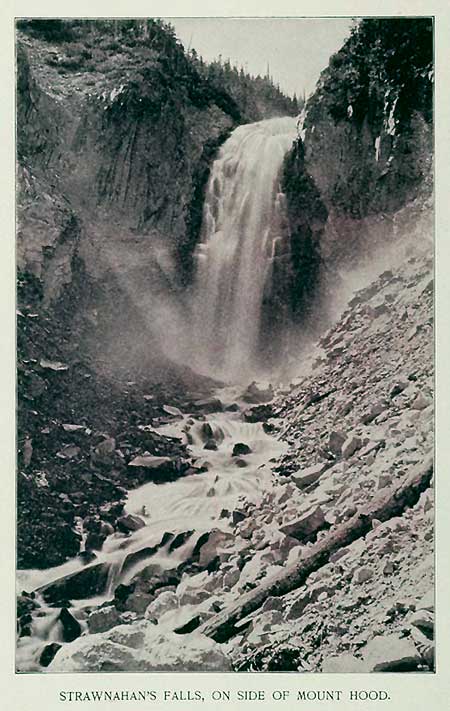

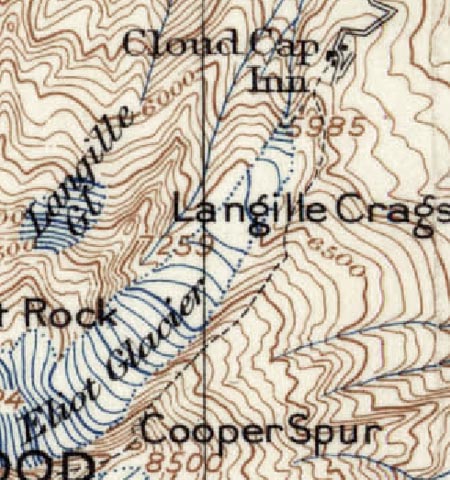

Similar rocky outcrops appear elsewhere on the mountain, forming Mississippi Head, Yocum Ridge, Barrett Spur and the Langille Crags. Hikers visiting Gnarl Ridge know the Newton Clark Prow from the many waterfalls formed by glacial runoff cascading over its cliffs.

(Click here for a larger version)

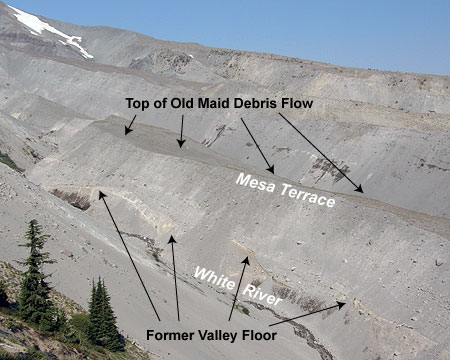

The much softer and less consolidated rock below the prow made it easy for the ice age ancestor of the Newton Clark to scour away the mountain. This action created the huge alpine canyons that Clark and Newton creeks flow through today, as well as the enormous U-shaped valley of the East Fork Hood River.

A Glimpse into the Ice Age

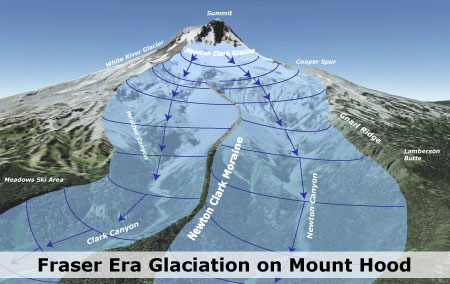

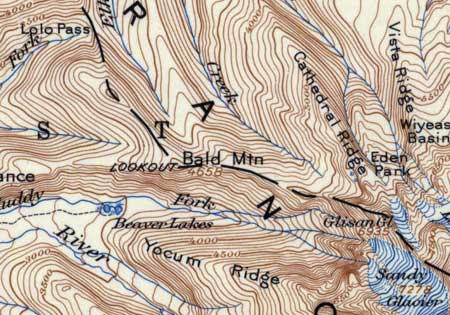

While today’s Newton Clark Glacier flows a little over a mile down the east face of the mountain, its giant ice age ancestor once flowed more than 12 miles down the East Fork valley (today’s Highway 35 route), nearly to the junction of today’s Cooper Spur road. At its peak, the ancestral glacier was more than 1,200 feet deep as it flowed down the valley.

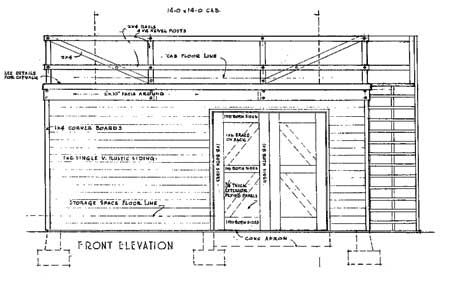

If you were to walk along the crest of the Newton Clark Moraine at that time (as suggested in the illustration, below), you would have likely been able to walk directly across the ice to Gnarl Ridge or today’s Meadows lifts, as the Clark and Newton Creek valleys were filled to the rim with rivers of ice.

(Click here for a larger version)

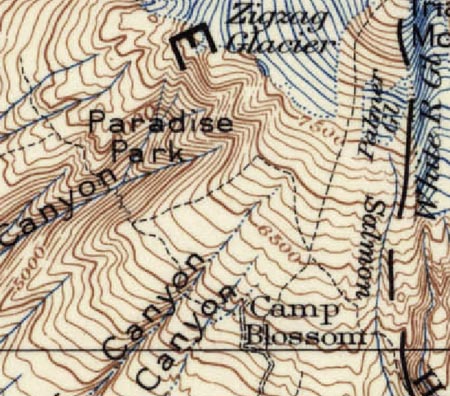

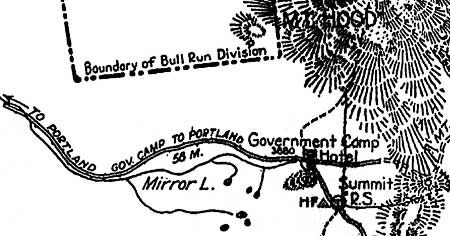

This most recent ice age is known to scientists as the Fraser Glaciation, and extended from about 30,000 years ago until about 10,000 years ago. At its peak, the zone of perpetual snow was as low as 3,400 feet, though probably closer to 4,000 feet in the area east of Mount Hood.

This means the deflation zone — the point in its path when a glacier is melting ice more quickly than snowfall can replace — was probably somewhere near the modern-day Clark Creek Sno-Park, or possibly as low as the Gumjuwac Trailhead, where today’s Highway 35 crosses the East Fork.

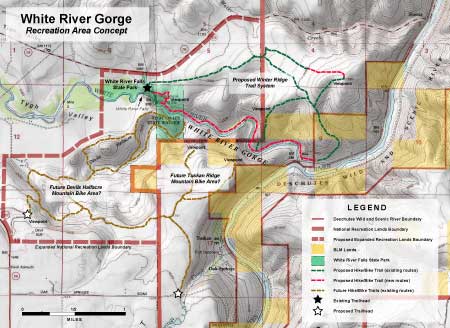

Below this point, the ancestral glacier would have changed character, from a white jumble of cascading ice to one covered in rocky debris, yet still flowing toward its terminus at roughly at modern-day confluence of the East Fork with Polallie Creek (the map below shows a very generalized estimate of the ancestral glacier)

Geologists believe the Fraser-era glacial advances followed the path of earlier glaciers in their flow patterns. With the Newton-Clark glacier, scientists have found traces of at least two previous glacial advances from even more ancient glacial periods that extended far down the East Fork Valley prior to the Fraser Glaciation. This helps explain the magnitude of the glacial features in the East Fork valley, having been repeatedly carved into an enormous U-shaped trough by rivers of ice over the millennia.

(Click here for a larger version)

The timing of the Fraser Glaciation is even more fascinating, as it coincides with the arrival of the first humans in the Americas. It was during this time — at least 15,000 years ago, and likely much earlier — that the first nomadic people crossed the Bering Straight and moved down the Pacific Coast.

Does this mean that the earliest humans in the region might have camped at the base of Mount Hood’s enormous ice age glaciers, perhaps hunting for summer game along the outflow streams? No evidence exists to show just how far humans pushed into Mount Hood’s prehistoric valleys, but scientists now believe people have lived along the Columbia River for at least 10,000 years, and the oral histories of some tribes in the region are also believed to extend back to that time.

How to See It

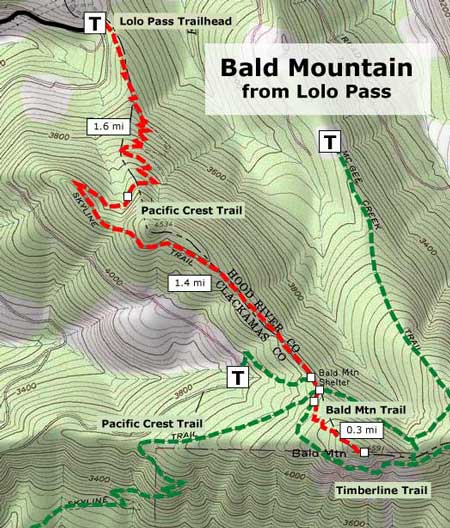

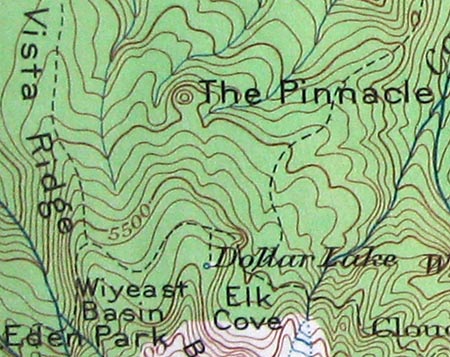

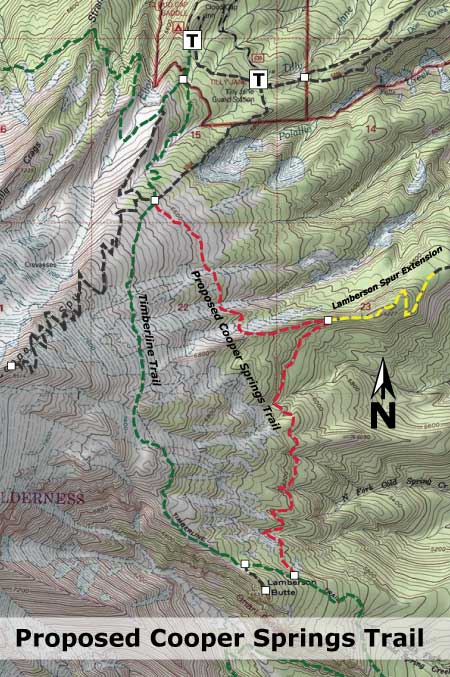

The best way to see and appreciate the Newton Clark Moraine is along the Timberline Trail where it follows Gnarl Ridge. This route offers a wide-open view across Newton Canyon to the moraine. You can also see the active geology at the headwaters of Newton Creek, where the slopes of the moraine continue to change every winter. On a breezy day, you might also notice sulfur fumes blowing over the summit from the crater — a reminder that Mount Hood is still very much a living volcano today.

You can follow a detailed hike description to Gnarl Ridge from the Portland Hikers Field Guide at the following link:

Portland Hikers Field Guide: Gnarl Ridge Hike

Another way to see the moraine is from rustic Bennett Pass Road. In summer, you can walk or bike along the old road from Bennett Pass, and there are several viewpoints across the East Fork valley to the headwaters and the Newton Clark Moraine. In winter, you can park as the Bennett Pass Sno-Park and ski or snowshoe to one of the viewpoints — a popular and scenic option.

The most adventurous way to visit is to simply hike the crest of the moraine, itself. This trip is only for the most fit and experienced hikers, as the final segment is off-trail, climbing high above the Timberline Trail. The reward is not only close-up look at the mountain from atop the moraine, but also a rare look at a series of spectacular waterfalls that can only be seen from this vantage point.

Whatever option you choose, you’ll have unique glimpse into Mount Hood’s past — and possibly its future — through one of the mountain’s most unusual geologic features.