The author with our current pack — Shasta, Whiskey and Weston

There probably isn’t a more divisive topic among hikers than whether dogs should be leashed on trails. To qualify myself, I’ve included a few images of me with the beautiful pack of dogs that pretty much run our lives. We love dogs (and cats). My wife and I have owned 11 in our nearly 41 years together, with plenty of time spent in the outdoors with them. For what they are worth, those are my bona fides for posting this opinion piece!

My own experience as a longtime dog owner informs me on a couple fronts in the debate over leashes. First, owning a dog is an ongoing learning experience where the humans become increasingly aware of what is (and isn’t) in their control when hard-wired canine behavior simply takes over, no matter how well a dog has been trained. Second, nobody can love your dog as much as you do, and — can it be true? — sometimes people might really dislike your dog! What is wrong with these people?

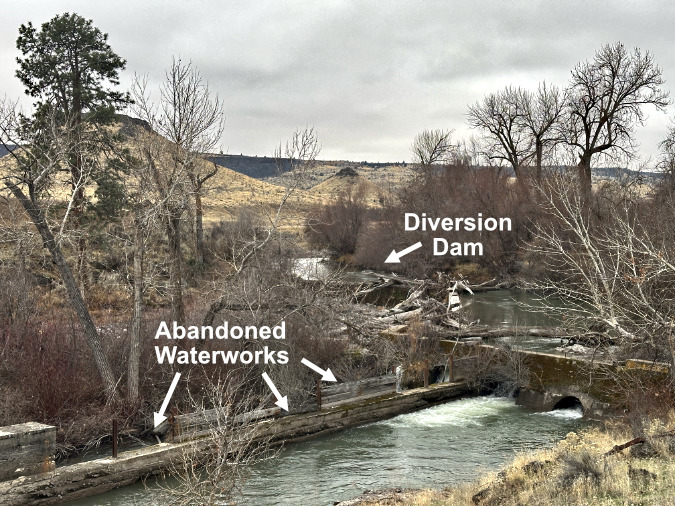

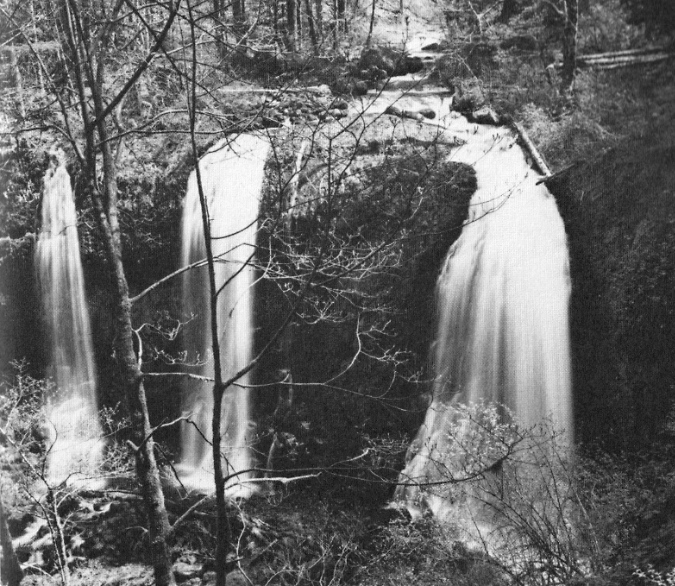

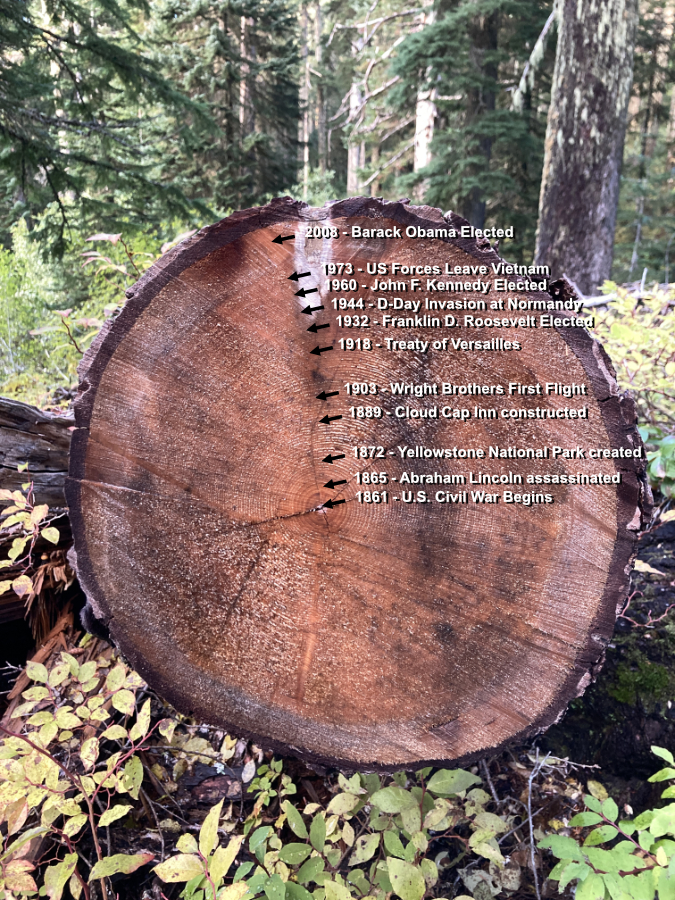

Dogs and exploring have gone hand-in-hand since the evolution of domestic canines. This rare trail scene is from around 1900 on the west summit of Lookout Mountain, with Mount Hood in the distance. Rover is even caught barking in this unusual image (head sticking in on the far left)

And thus the ongoing debate over leashes and trails. It really shouldn’t be a debate, because dogs should ALWAYS be in a leash on hiking trails. If they need a space to play unleashed, and don’t have room at home or a fenced backyard, then a dog park is semi-safest bet. Otherwise, when dogs are outside the home, they should be on a leash – especially on hiking trails.

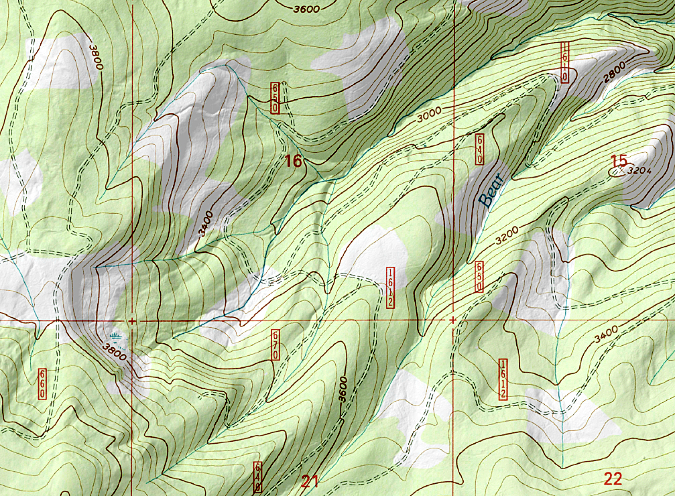

Why? Aren’t trails meant to be a place where both you and your dog can escape the stresses of urban life and become immersed in nature? Absolutely. But as a physical space, trails are narrow, confined spaces, often in steep terrain with little room to navigate approaching hikers – or for other hikers to navigate you and your dog. This is especially true for our most popular trails, where you likely to encounter many other hikers, often with their own dogs. Keeping your dog on leash is as basic a gesture of mutual respect for others in sharing the trail. And while we humans find roaming a tree to be a stress-buster, dogs are usually more stressed off-leash than on one. They’re pack animals and leashes (with the pack leader at the other end) help maintain the pack order they crave.

Oregon Humane Society Technical Animal Rescue Team (OHSTAR) volunteers in 2014 rescuing an off-leash dog that had fallen over a 150-foot cliff in the Columbia River Gorge. Most don’t survive these falls (photo: OHS)

Leashing your dog also protects it from harm, especially from other dogs. Dogs on trails behave differently than they might at home, including how they interact with other dogs they may perceive as a threat in an unfamiliar place. Unleashed dogs in WyEast Country also fall from cliffs in the Columbia River Gorge with regularity, and usually don’t survive. Rescuing those that survive the fall often involves putting volunteer crews at risk. This is why the Oregon Humane Society (OHS) recommends always keeping your dog on a leash when on the trail.

Perhaps most compellingly, leashing your dog helps avoid traumatizing other people who may have a deep fear of dogs, especially large dogs. This includes young children inexperienced with dogs, and whose lifetime perspective comes from their earliest encounters with animals, especially big dogs.

When leashes are required… should you say something?

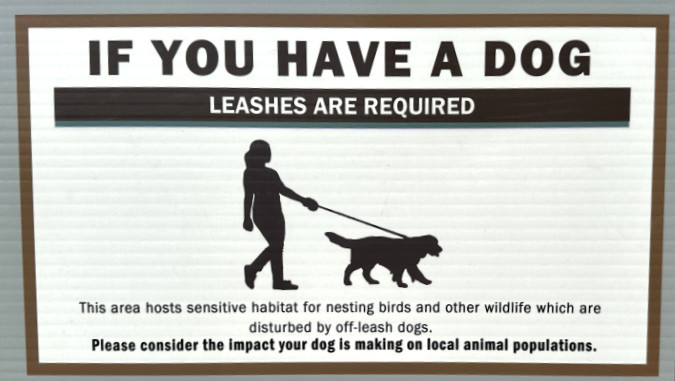

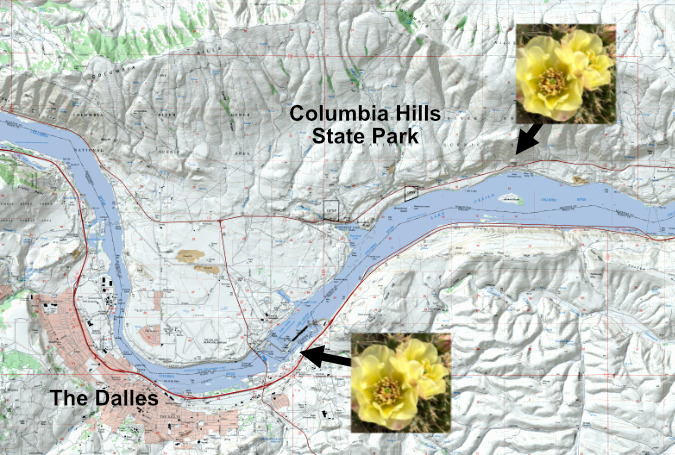

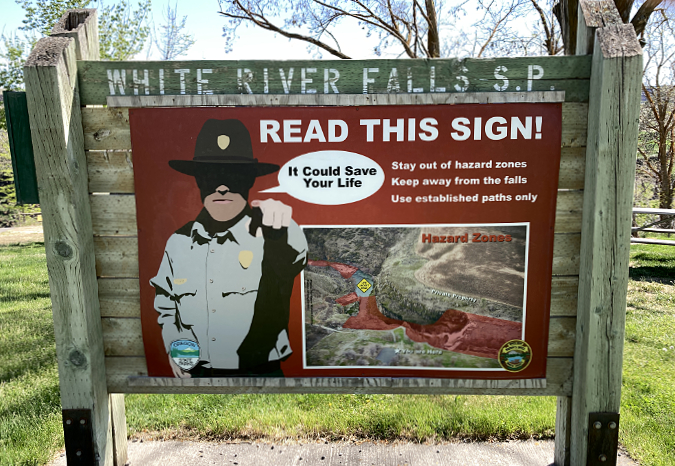

I hiked the Labyrinth Trail in the east Columbia River Gorge a few weeks ago, and noted the obvious sign at the trailhead: leashes required from December 1 through June 30. Winter and early spring are my preferred seasons for this trail, so it has been an ongoing frustration of mine to see so many people flouting this simple rule. After all, it’s intended to protect wildlife during a vulnerable season, who could disagree with that? Normally, I just grit my teeth and greet folks in a friendly way, but with a thought bubble that says “didn’t you SEE the sign?”

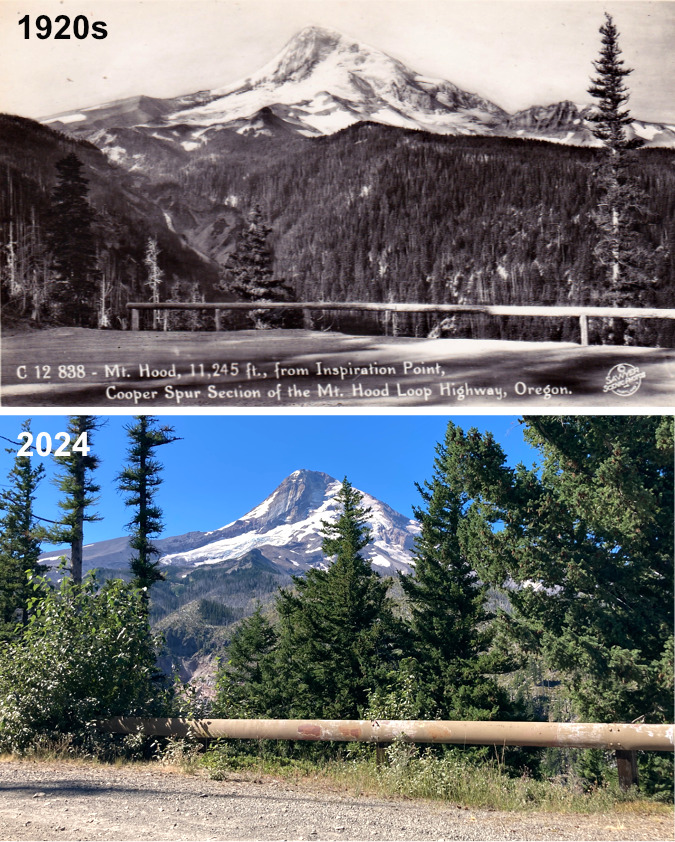

Yes, this signpost at the Labyrinth Trail is busy and somewhat confusing….

…but the leash requirement is quite clear!

Within a minute of taking the above photos, two hikers came from behind me with a pair of dogs off-leash, glanced at the sign, and walked right by without pausing to leash their pups. Emboldened by my recent high-speed chase for my stolen backpack, I decided to self-deputize as a ranger for some enforcement of my own that day, and speak up to people who had their dogs off-leash. I made the trip an experiment in “reminding” folks of the seasonal leash requirement. The response was not what I expected!

Over the course of that cool, clear Sunday afternoon, I encountered eight separate groups of hikers with dogs. Seven groups were on the main trail, and of these, only two had their dogs on-leash. The eighth group was walking along the abandoned section of highway that leads to the signed trailhead, and had two dogs on leash. Of the five groups who had dogs unleashed, the degree of roaming ahead of their owners varied largely based on size, with big dogs much more likely to roam.

How did people respond when some greybeard stranger confronted them about their off-leash-dog? There were a variety of reactions, though I’m pleased to say that I gradually perfected a non-threatening (I think) approach to my newly self-deputized role of The Enforcer.

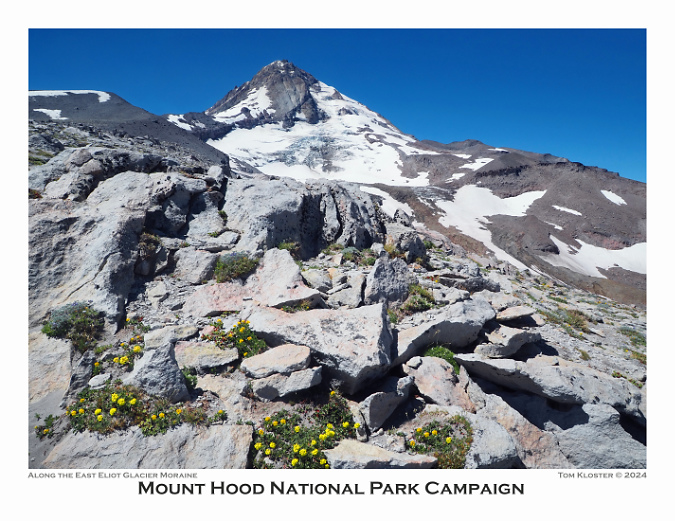

This pup is properly leashed on the high slopes of Mount Hood, protecting alpine wildlife who have little cover at this elevation

On my first encounter, the owner seemed startled and surprised that anybody would say something about their off-leash dog. I opened the conversation with “Hi, just FYI this trail is on leash-only this time of year.” They broke eye contact and muttered something that sounded like “oh, okay…”. I responded with a cheerful “have a nice hike!”.

It felt very awkward. While I always greet people I see on the trail, it’s usually just to wish them a nice hike. Commenting on their off-leash dog came across as a scold, something I wouldn’t want to be on the receiving end of, nor is my nature to do. I don’t know even how effective the “scold” was on this firsts encounter, as the person certainly didn’t pause to leash their dog as they scooted down the trail in the opposite direction.

The next encounter is one I rehearsed when I saw a pair of big dogs running wild in the short video clip that I captured, below. I really wanted to talk to this group because these dogs were roaming well beyond sight of the owners. This is clearly the impact on wildlife that leash rules are intended to minimize, let alone the impact on other hikers — especially those with their own dogs. Alas, I never did catch up with this group, though I did hear much whistling and loud calling as they attempted to keep their unruly dogs within sight. I wondered how many other hikers might have had their day on the Labyrinth Trail spoiled by unwelcome encounters with this group? Or wildlife that had been terrorized or even harmed?

Dogs gone wild on the Labyrinth Trail…

Next, the pair of hikers with three dogs in the second part of the video approached me. This was the same pair that had walked right past the trailhead sign. I attempted a smoother, more sympathetic delivery on this encounter: “Hi, how are you? Hey, you might not know, but this trail requires a leash this time of year. It’s sort of hidden on the trailhead sign.” That’s not remotely true, of course, but I wanted to try something less threatening in this round.

One of the hikers said in a rather surly reply “well WE didn’t see any sign“ and the other simply looked quite annoyed that I had dared to say anything at all. Thud. Clearly, my smooth, low-key delivery hadn’t worked. So, I replied “no worries, not trying to be a jerk, I just thought you would want to know. Have a great hike!” Silence.

I’m not sure how that last part landed with this pair, but there is zero chance they had not seen the sign at the trailhead, nor did they bother to leash up their dogs as they headed off from our exchange on the trail. Did they actually read the sign on some earlier visit? Hard to know, but from my vantage point they walked right past it, as if they had hiked the trail many times. Most of us stop to read directional signs, after all, especially if we’re not familiar with the trail.

While I’d like to give them the benefit of the doubt, more likely they just decided the rules do not apply to them. That was the vibe I got from our brief exchange, and therein lies one of the great obstacles to posting leash requirements on trails without any enforcement. Some people really just don’t care, unfortunately.

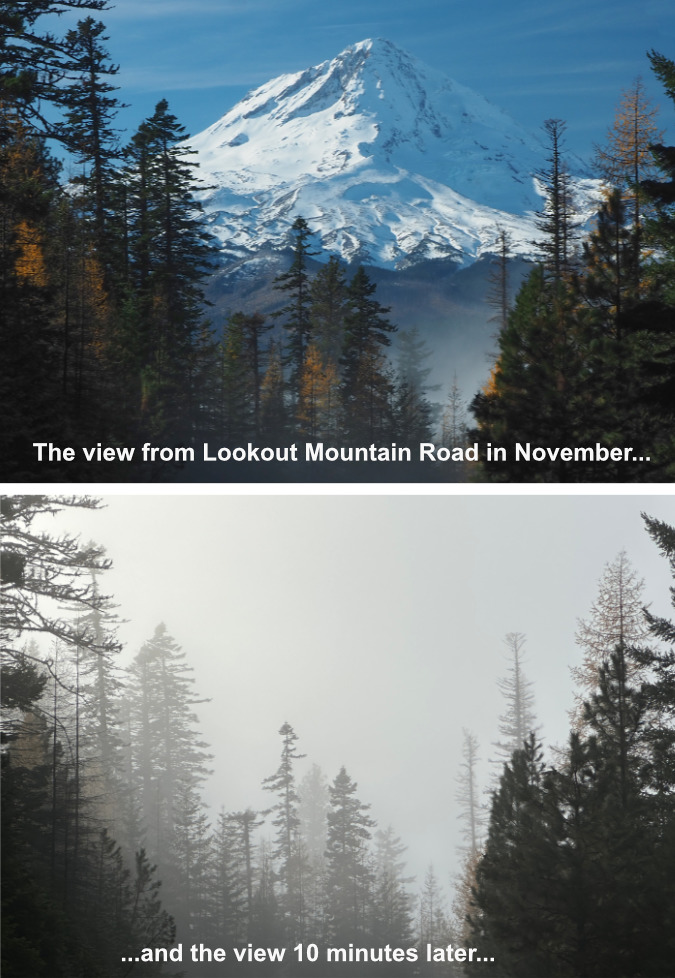

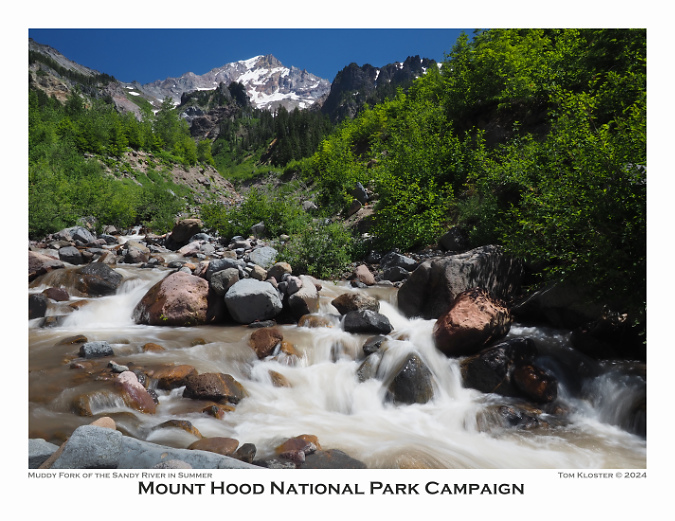

This dog on the Cooper Spur Trail should be on a leash. Big dogs can terrorize a lot of wildlife in open terrain. On Mount Hood, unleashed dogs also regularly chase wildlife onto loose glacial canyon slopes, sometimes becoming stranded and requiring rescue

The next two sets of hikers had their dogs on-leash, so I decided to complement my self-appointed policing with some unsolicited praise. The first was an older hiker with an adorable dog that looks like it might have been an unlikely Corgi – German Shepherd mix. I greeted them with “Hi! Thank you for keeping your dog on leash!”

The hiker smiled (I think the dog did, too) and replied that it was the only way they could really keep track of where their low-to-the-ground dog was, and that they worried about it tangling with a rattlesnake or other hazards off trail. That’s a responsible dog owner! I’ll return to those potential hazards later in this article. I wished them a good hike and moved on.

Even little dogs should be leashed. Though they may not be scary, even when they approach grownups aggressively or barking, they can be terrifying to youngsters. This hiker is setting a great example by leashing their small dog in the Mount Hood Wilderness

The second group with their dog on-leash was a young couple with a roughly six-year-old kid and a very friendly golden retriever. I said “Hi! Thank you for leashing your dog, not many people are today!” Then, thinking about impressionable young ears, I added “I think the leash requirement is to protect wildlife this time of year.“

The couple beamed and were very receptive. I’m going to guess they spent some time talking to their youngster about this as they headed up the trail – hopefully, anyway. They were setting a really good example, and what kid doesn’t want to watch out for wildlife?

Family outing to Elk Cove with their beautiful, big dog properly leashed — and they even posed for me!

I continued to fine-tune my comments as I encountered still more hikers with off-leash dogs.

“Hi! Beautiful day up here! Hey, just letting you know that this trail requires a leash this time of year. Your dogs are beautiful! Have a good hike.”

“You, too!” they called back to me with smiles.

Bing! Bing! Bing! It turns out that dog platitudes are the secret sauce – of course! In both cases where I tried this approach, they even thanked me for giving them a heads-up. Truthfully, a couple of these dogs were downright homely, but they were beautiful to their owners, and that’s all that matters — as any dog owner knows.

This dad is setting a good example for his son at Horsethief Butte. Leashing your dog on trails is a great way to help youngsters understand the importance of protecting wildlife and respecting other hikers

Take-aways from my self-deputized stint as leash-enforcer? Most people follow the rules, or are at least open to following the rules. Yes, there will always be those who knowingly exempt themselves from the rules the rest of us choose to live by (and yes, people with that mindset are having a bit of a moment in our society right now), but most people appreciate the concept of The Commons — and our responsibility as individuals to protect it from tragedy.

Better signage where leashes are required could build on these generally good intentions. At the Labyrinth Trail, the signage is a part of the problem. While simply stating regulations in rather dry fashion at trailheads is the default on our public lands, here’s another way this could be conveyed both firmly, and in a more explanatory way at the Labyrinth:

Clear, concise and visible…

Too pollyannish? Okay, here’s an alternative version for the more self-centered hiker with dogs:

When altruism doesn’t work, try fear…

These examples are also important in their location. By the time most people get to the Labyrinth trailhead, they have already hiked a fair distance an abandoned highway section that functions as the access trail from Rowland Lake. Before my creative license was applied, here’s the actual sign that greets hundreds of hikers who park here every week to hike the Labyrinth Trail:

The existing signpost could use an upgrade!

Fair enough, but this would be a great spot to post the leash rules where dog owners can still fetch (ahem) a leash from the car, or perhaps even decide to pick another trail. The existing sign post was installed by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, so it would require some agency coordination, as the Labyrinth Trail is on U.S. Forest Service land, but I suspect the two could agree in the interest of protecting wildlife.

Just beyond the “no overnight parking” signpost is one of the more obscure signs in the Columbia Gorge:

This is one solution to wood signposts that rot off at the base…

Whoever installed this hunting sign meant business: it’s bolted to a basalt boulder… which also means that hunting season is every season? Maybe this could also be a spot to talk about the on-leash season and its purpose?

Another problem with the Labyrinth leash rule is that it’s way too complicated for most to remember. On-leash season starts on December 1? Or was it December 30? And it ends on June 30 …? Or was it June 1? Or May 30? Add in the May 1 to November 30 equestrian season, and this is the sort of trailhead word salad that people begin to tune out.

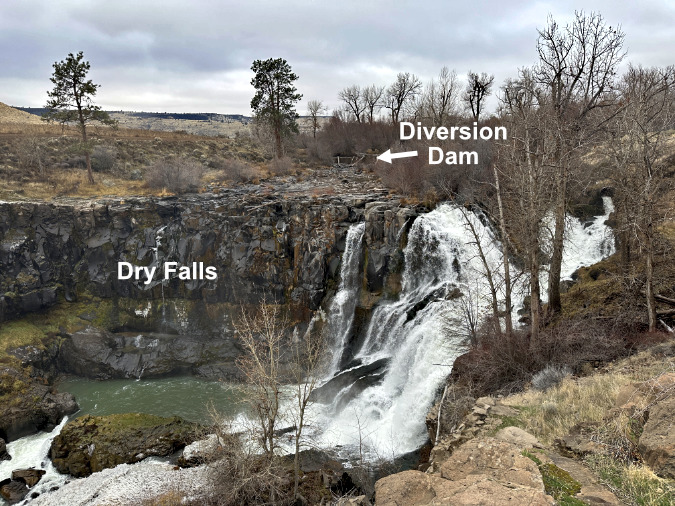

Meanwhile, just a few miles to the east (below) at the Catherine Creek trailhead, leashes are required year-round on trails that are inter-connected to the Labyrinth trial network (below).

The Forest Service has a tighter leash on its dog policies at nearby Catherine Creek, including a bit of explanation to educate pet owners

Though the conflicting policy is confusing, this is much better, and kudos to the Forest Service for drawing a bright line with leashes on the Catherine Creek end of the trail system. More leash-rule signs should follow the Catherine Creek model. Protecting wildlife and other hikers is important, and making this point clearly and prominently where people park, before they head up the trail, is as important at the message, itself.

The Catherine Creek policy also gets it right on leashes, overall. Given the many good reasons for alwayskeeping dogs on leash, complicated seasonal requirements don’t make much sense, and only serve undermine the main goal of protecting wildlife if hikers are confused.

Kids and wildlife are the best arguments for leashes

I have been charged many times by loose dogs whose owners are far behind or out of sight. Fortunately, I have never had to harm one by defending myself with a hiking pole, but I’ve come close on a couple occasions with a couple of big, snarling dogs. Inevitably, the owners catch up, and — usually embarrassed — apologize that “Fido is never like that at home!”

Think your dog is under “voice control”? That’s a fallacy – especially with a puppy like this one seen on the McIntyre Ridge trail. Were it to wander off and become lost, the chances of this young dog surviving in a wilderness would be slim

In these moments, I’m usually irritated enough that I don’t say anything at all, but in my new, more forward mindset, I already have a response: “But Fido isn’t home, is he? And neither are you. So unless he’s on a leash with you at the other end, this is how you should expect him to respond to a stranger. He’s a dog.”

Well, I’ll say that in my unspoken thought bubble, at least — but it’s quite true, and any dog owner should know this. Most dogs are not themselves when they’re out on a trail, away from home.

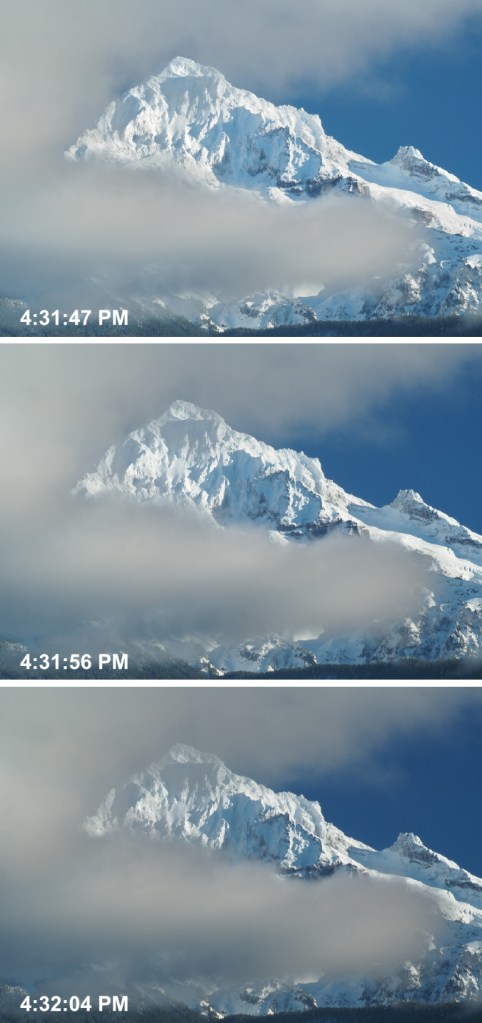

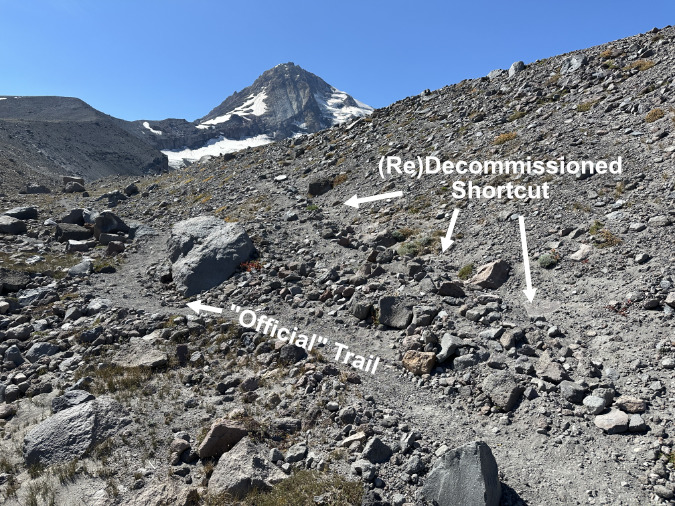

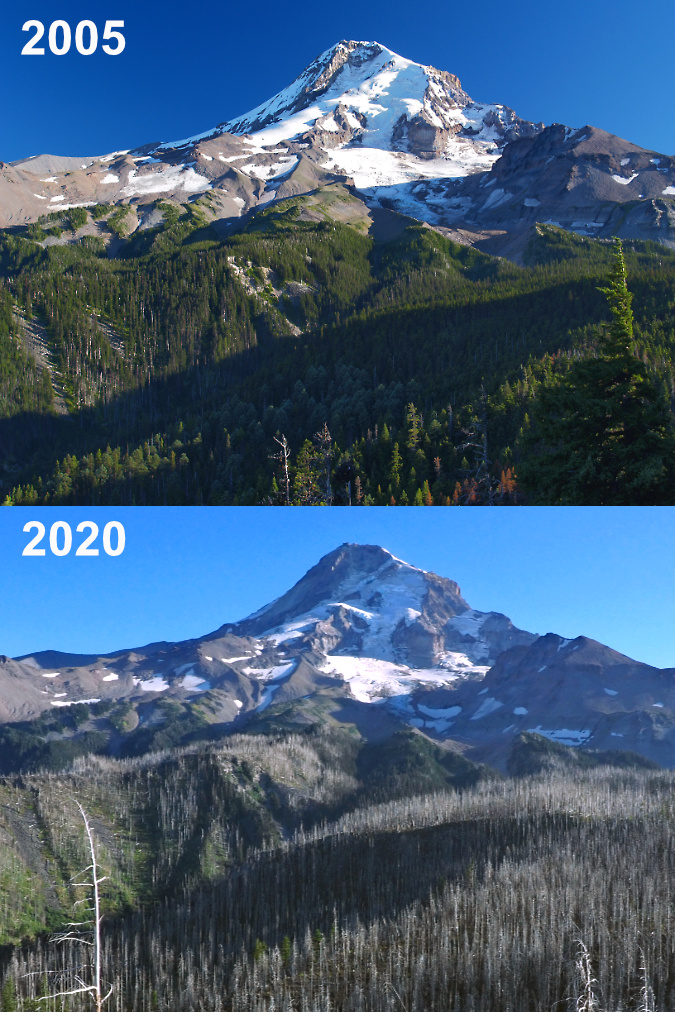

I’ve also watched several off-leash dogs chase down wildlife, from tiny pikas to rabbits and deer. I was hiking on Mount Hood with a friend once and they commented on the lack of marmots compared to Mount Rainier – a national park where dogs are simply not allowed on trails. I knew the reason, but a few years ago I was able to catch a canine culprit in the act just west of Timberline Lodge. These hikers (below) had climbed past me, and they were just beyond this section of trail when their roaming dog took off in a sprint.

Fido way out ahead, looking for wildlife to chase down..

I already had my camera out, and photographed the dog as it chased a terrorized marmot down the rocky slope on the right (see below), across the snowfield and up to the marmot’s den, under some boulders on the left side of the snowfield. The owners were yelling helplessly as the dog attempted to dig into the marmot’s den at least 100 yards away from them. For its part, the marmot climbed up on the boulder and tried frantically to distract the dog. Why? Probably because this was in late spring and it may have had a litter of pups in its den. Marmots give birth to litters of just 3-8 young every other year, so they’re highly vulnerable to natural predation, never mind unruly dogs.

[click here for a larger view]

None of this incident was the fault of the dog: it was just being a dog. The owners? They were just being thoughtless. Did they leash their dog after this incident? Nope. Why would they? The official pet policy for Mount Hood National Forest requires leashes “in developed areas” (that legal definition is left to visitors to figure that out). Otherwise, the Forest Service simply requires that “all dogs must be within sight of the owner and in complete voice control.”

That last part is the real misnomer. There is no such thing as “complete voice control” of a dog, especially out in nature. The illusion that this level of discipline even exists results in lots of sad signs posted at trailheads where an off-leash dog has been lost in the woods. The cruel reality is that most these lost dogs will likely die from exposure to the elements, injury or even predation — not something any dog owner would wish for their pet.

Posters like this get me every time, and I see them all the time at trailheads. Losing one pup in a rugged area like the Hatfield Wilderness is heartbreaking, but two? I don’t know if these dogs were ever found, but the risks of falling or getting stranded on a cliff in the Gorge have needlessly claimed many dogs over the years

While impacts on wildlife can seem a bit abstract when drawing the line on leashes, a more compelling argument comes when off-leash dogs terrorize young children on trails. It’s more common that most of us would like to believe, and usually only reported when a child is injured (or worse) by an off-leash dog. Young kids are disproportionally attacked by dogs compared to adults, accounting for more than half of all dog bite victims. Kids four years and under are also the most likely to be fatally attacked, a horrific outcome to consider.

A more far-reaching impact is on the untold number of young kids who are traumatized by an off-leash, out-of-control dog on a trail. This isn’t even a factor in most land agency leash rules, but for our broader society, it could be the most lasting. It’s so widespread, it has a name: cynophobia, or the fear of dogs, with most adults reporting that this condition began with a terrifying childhood experience. An off-leash dog aggressively rushing a youngster on the trail might not result in a dog bite, but it could needlessly be cheating that child of a lifetime of the joy that having a pet offers by instilling deep fear from an early, scary encounter.

Young kids and off-leash dogs — especially big dogs — don’t mix on trails. These moms are setting a great example on the Wahclella Falls trail by leashing the family dog on this popular path

With a crazy quilt of uneven, confusing and mostly ineffective public land leash rules, most trail users are poorly informed on the true risks and impacts of having their dogs off-leash, while some folks are just plain defiant their perceived right to let their dog run loose.

Only in our national parks (and a few local parks, like Metro’s in the Portland region) is there a serious effort to manage dogs, and usually with a fair amount of grousing from dog owners. While the National Park Service has been especially fearless in how they manage dogs, other state and federal land agencies continue to be wary of confronting the issue. So, is this a problem that can even be fixed?

It’s on us…

Unfortunately, the public agency reluctance won’t be solved anytime soon, as the lack of continuity in leash rules simply reflects the lack of consensus – and knowledge — among dog owners. Therefore, it’s really up to us as hikers and dog owners to change the culture of off-leash dogs. The days when dogs could run free on our trails on public lands are long over, both because of the sheer number of people using our trails, but also because we now know of the impact it has on wildlife, the environment and our dogs.

That’s not a pack on the hiker in the back — it’s their injured 30-lb dog that they were carrying out of the Mount Hood Wilderness. Keeping a dog on-leash is the best way to keep it safe from injury on the trail – though in this case, the trail proved too much for the dog, and it would have been a safer call to simply leave Fido at home for this hike

Is it possible to foster a new, grassroots leash ethic for dogs? Of course! After all, not many people toss garbage out the window when driving these days, though this was common practice until the anti-litter campaigns of the 1960s and early 70s. Those efforts grew from local, grassroots efforts that changed both our ethics and laws. Recycling began in the same way in the 1970s, first as a grassroots movement, and eventually transforming how governments manage waste collection.

Hikers with dogs began their own ethics conversion in the late 1990s with poop bags, an outgrowth of the Leave No Trace movement that has now become mainstream. Yes, people forget to pick up their poop bags on the way out (pro tip: tie them to your pack — yes, you read that correctly), but only a few leave them behind when you consider how many dogs and hikers are using our most popular trails. The overall benefit is still very good.

This hiker set their poop bag on a stump, presumably to help remember it on the way out?

These hikers went for strength in numbers, but the best plan is to tie it to your pack. Nobody wants to see forgotten poop bags on the trail!

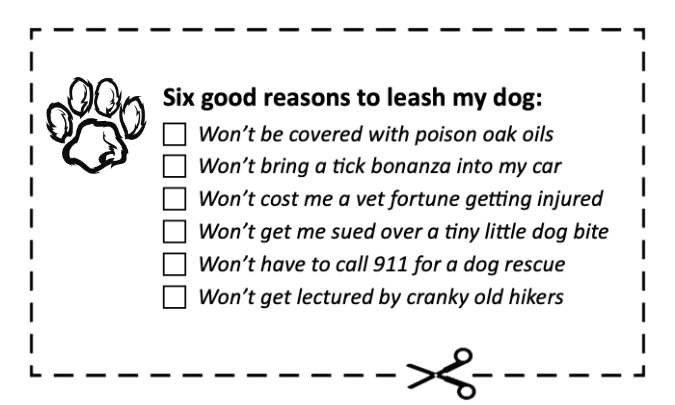

How do we start a new on-leash ethics movement? Why not online? I probably don’t have the pull with Mark Zuckerberg to add a trending “My dog is leashed!” badge to Facebook or Instagram, but short of that… why, I can at least post some handy (and somewhat facetious) clip ‘n save wallet cards on my obscure blog to download and share!

I’ve provided two versions to reflect our divisive times. The first appeals to the recent lurch toward self-involvement and me-ism that is reigning in our current political climate. This clip-n-save card speaks to the self-interest in all of us – like it or not:

Card for the times..?

But for those who seek a higher philosophical plane — and perhaps defying the current political zeitgeist — please join me in carrying this more altruistic version:

Card for the caring!

Conflicted? You can carry both! Better yet, we can all simply adopt these principles in our everyday trail ethics. Whatever our motivation, the facts argue for keeping dogs leashed on trails, simple as that. The first step is knowing the facts — clip those cards — and especially the risks of letting Fido run wild. Who knows, we might just change our little corner of the world?

The author back in 2009 with our big (and little) dog pack — Borzoi sisters Joker and Jester and our little rescue Whippet Jinx. He thought he was a borzoi, too… and so did the girls!

Thanks for reading this far, and for caring about our public lands in WyEast Country. I hope to see you and your (lovingly leashed) dogs on the trail, sometime!

___________

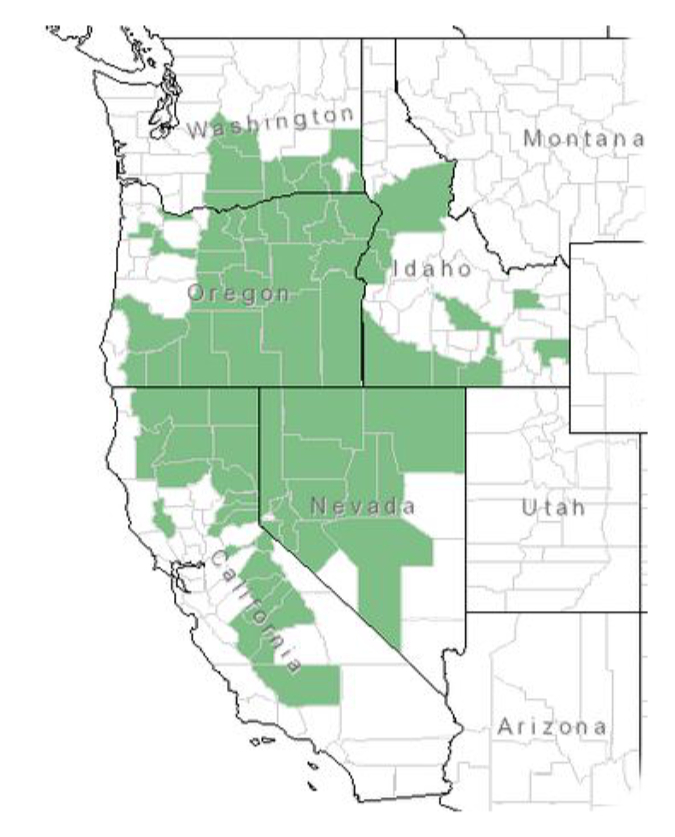

Postscript: I’ll close this article with another acknowledgment that our federal lands workforce are under unprecedented, highly personal attack by a new administration stacked with political appointees chosen for their radical, fringe views toward the environment, and who are openly hostile to the very concept of public lands that belong to everyone. The attacks are reckless, cruel and purposely vindictive to the perceived “enemies” of the regime.

In just the past two weeks, thousands of Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management and National Park Service workers have been fired for the crime of being recently hired, or having accepted a promotion or new position. It’s outrageous, illogical and probably illegal, but that doesn’t make it any easier for the public servants who have been targeted.

U.S. Representative Cliff Bentz answering to a one of four overflow town hall crowds last week across Eastern Oregon that confronted him over the attack on the federal workforce last week

We’ll be on defense on this front for the next few years, unfortunately. So, at this moment, it’s especially important to share our unequivocal support for the federal workers who have devoted their careers to caring for our public lands. We can all do that with kind words when we see them working in the field, by helping them care for the land, and by pushing back on disinformation wherever we see it.

Hundreds turnout out in Gresham last weekend to press freshman U.S. Representative Maxine Dexter to do more to push back on the attack on federal agencies (photo: OPB News)

We can also act by voicing our support for public lands and federal workers to our congressional representatives and senators. It really does work. Oregon’s lone Republican in Congress recently got a loud taste of it when he ventured home to what he thought would be a just another series of safe, sleepy town halls in his Eastern Oregon district. Instead, he faced overflow crowds of angry, deeply concerned constituents.

Other Oregon representatives have seen similar town hall turnouts and are reporting thousands of phone calls from concerned constituents, and they are scrambling for ways to be accountable. This is already having an impact! More to come, of course, but the tide does seem to be turning…

_________________

Tom Kloster • March 2025