20 years later, it’s hard to imagine the massive debris flow that roared down the verdant Muddy Fork valley in 2002…

Earlier this year I posted a “then-and-now” look at the changes to the Cooper Spur area on Mount Hood’s east flank over the past 20 years, including dramatic changes to the Eliot Glacier. This article provides a similar look at forces of nature that have once again reshaped the Muddy Fork canyon, on Mount Hood’s steep western flank.

The story begins in the winter of 2002-03 with a massive debris flow triggered by a landslide in the upper Muddy Fork canyon. The event occurred sometime during the winter season, when deep snow-covered hiking trails, and thus went unnoticed until the snowpack cleared that spring. The event immensely powerful, mowing down whole forests and raising the valley floor of the upper Muddy Fork by as much as 20 feet. Whole trees were snapped off and carried downstream with the debris, forming huge piles that still give mute testimony to the power of the event.

Stacks of downed trees still give mute testimony to the violence of the 2002 event

Though the exact origins of the initial landslide remain unknown, the event was probably not triggered by a collapse within the Sandy Glacier that looms above the Muddy Fork, as there were few signs of the debris flow near the glacier, above the section of the upper canyon where the landslide scars were obvious. Instead, the debris flow likely began as a major slope collapse within the steep confines of upper canyon, where the Muddy Fork tumbles between sheer rock cliffs and steep talus slopes.

The scars from the 2002 collapse are still plainly visible today (below), but the debris fields it created downstream are rapidly being reclaimed by new forests. The landslide created new cliffs and steep walls within the upper canyon, including new waterfalls along the Muddy Fork where the stream suddenly plunged over the newly exposed bedrock.

The massive 2002 cliff collapse in the upper reaches of the Muddy Fork canyon gave birth to a debris flow that spread for miles downstream

Below the cliff-lined section of the upper canyon, the debris flow fanned out, spreading the landslide debris across the broad floor of the Muddy Fork valley. Nobody witnessed the event, so it’s unknown exactly how it played out. However, the wide debris fields of rock and sand clearly resulted from a major event, as did the complete removal of a standing forest.

Trees swept up in the flow were stacked in piles that suggested a lot of water content in the debris flow – as much mud as it was rock – due to saturated winter soils and possibly a sudden snowmelt, perhaps from an unusually mild winter storm. Whole trees were rafted on their sides until they were beached in giant log jams against forest stands along the valley margins that somehow survived. Evidence of the flow only became apparent when hikers returned that spring to find the Timberline Trail completely erased where it had crossed the Muddy Fork.

The raw cliffs and talus slopes surrounding McNeil Falls are still recovering from the event after 20 years

Over the course of the two decades that have since passed, the Muddy Fork quickly cut through the new debris to reach the old valley floor, revealing splintered stumps from trees that were snapped off during the event, then buried in the debris (below). This has confined the stream to a deep channel in the upper valley that limits its once-meandering ways across the valley floor, at least for now. However, the event only affected the north branch of the Muddy Fork, leaving the south branch almost untouched.

Large trees by the thousands were snapped off and upended by the debris flow, then buried on the floor of the Muddy Fork valley

The Muddy Fork quickly excavated a new channel in the debris flow, unearthing trees like these that had been buried on their sides under the debris

While the north branch is currently confined to its newly cut channel, this is a temporary condition. Debris flows along Mount Hood’s glacial streams are a nearly constant reality, and even major events like the one that occurred on the Muddy Fork in 2002 are not uncommon. As jarring as these events are to witness, they also give us a privileged glimpse into the very processes that have shaped the mountain we know today. In time, smaller debris flows will gradually choke the current channel with debris, and the Muddy Fork will once again meander across the valley floor – just 20 feet higher than it was in 2002.

The Muddy Fork debris flow then… and now

Though it wasn’t apparent to casual visitors from a distance, hikers who knew the mountain immediately spotted the debris flow from the open slopes of Bald Mountain, where the Timberline Trail provides a sweeping view of Mount Hood’s west face. Before the debris flow, the two main branches of the Muddy Fork had similar floodways at the head of the valley, below the Sandy Glacier. As the 2003 image (below, left) shows, the north branch was suddenly much wider. Today, forest recovery has nearly erased signs of the debris field (below, right) from this vantage point.

[click here for a large version of this photo pair]

A closer look at this photo comparison reveals the scale of the debris flow in the summer of 2003, shortly after the event (below, left). The debris field was up to 1/4 mile wide and left up to 20 feet of debris in the channel of the north branch of the Muddy Fork. After 20 years (below, right), a carpet of green, recovering forest has already reclaimed much of the new debris field.

[click here for a large version of this photo pair]

Down at ground zero, the scene at the head of the Muddy Fork valley in 2003 (below, left) was of astonishing destruction. Whole forests were toppled and piled like matchsticks along the margins of the debris flow, pushing into standing forests just high enough on the valley walls to have escaped the waves of debris.

Twenty years later (below, right), most of the forest debris remains, though new logs were added to the jumble in the September 2020 wind event (described in this WyEast Blog article) that swept over Mount Hood. The new, mostly decidious forest rapidly emerging on the debris flow can also be seen in the 2023 image as the bright green band in the mid-background.

[click here for a large version of this photo pair]

The debris flow was still raw and unstable in the summer of 2003 (below, left), but after 20 years, a dense young forest (below, right) of Red Alder, Cottonwood and scattered Douglas Fir is quickly stabilizing the debris field. The health and vigor of this young forest growing on a 20-foot layer of boulders, gravel and sand is testament to the remarkable fertility of volcanic soils. While this new deposit contains almost new organic matter or true soil, the mineral content is rich in iron, potassium, phosphorus and other mineral nutrients essential to plant growth.

[click here for a large version of this photo pair]

Red Alder and Cottonwood are no surprise, here. Both are pioneer species known for their ability to colonize disturbed areas – but the presence of Douglas Fir is a surprise (two can be seen in the foreground of the 2023 image). If the young firs growing within this largely deciduous new growth can keep pace with their broadleaf neighbors, the new forest could begin to be dominated with evergreen conifers within a few decades, speeding up the succession process that typically unfolds in a recovering forest.

Looking downstream (west) from the center of the debris field in 2003 (below, left) provided a true perspective on the scale of the event, with large debris deposits mounded against heaps of stacked, toppled trees. After 20 years, the recovery (below, right) is rapidly obscuring the view, though Bald Mountain can still be seen over the young tree tops. The tallest of the young trees in the 2023 view are Cottonwood and most of the smaller tree are Red Alder. The conifer in the foreground is a young Douglas Fir – roughly 15 tears old and about eight feet tall.

[click here for a large version of this photo pair]

Turning back (east) toward the mountain from roughly the same spot, the view in 2003 (below, left) revealed a new channel through the debris that the Muddy Fork had almost immediately begun excavating. By 2023 (below, right) the channel has been widened over the years, though its depth has since stabilized at the old valley floor level. The second photo also shows the new forest quickly hemming the channel in from both sides.

[click here for a large version of this photo pair]

Still, the Muddy Fork is a glacial stream, and therefore volatile. It continues to expand, then refill its new channel with debris from smaller flood events that occur almost every year.

On one of my first visits to the debris field, I spotted a row of tree stumps (below) that marked the original valley floor – or perhaps an ancient valley floor? In this spot, the Muddy Fork had cut down through the loose flow material, exposing these sure markers of a former level of the valley floor.

One surprise is how quickly the Muddy Fork settled in to its new landscape after the debris flow. As these photos show, the stream quickly cut its way to the former valley floor then mostly stopped cutting any deeper in the many years that followed, despite its famously volatile flow. These stumps – and even the two large boulders to the left – remain today much as they were 20 years ago, despite being directly adjacent to the stream and exposed to the many flood events that occur here.

[click here for a large version of this photo pair]

Looking downstream (below) from just above the spot where the stumps were revealed, you can see how little change to the new channel has occurred since it was initially carved in the year after the event. The large boulder on the lip of the channel (left side of these images) is still perched there – and the three Noble fir growing it that survived the original event are still thriving today, nearly twice as tall.

[click here for a large version of this photo pair]

The most notable difference in the above photo pair is how debris has begun to refill the channel, as evidenced in the 2023 photo on the right. This process will continue over time until the channel has filled and the Muddy Fork is once again meandering across the main valley floor.

I don’t have good photo records of the narrow, upper canyon of the north branch Muddy Fork from prior to the 2002 debris flow. However, I have seen both photos (and even paintings) of this idyllic scene from the 1980s and 90s that show a waterfall here. Based on those earlier images, I do think that a single waterfall existed before the debris flow, roughly where the new falls is located today. Waterfall hunters have dubbed this “McNeil Falls”, referencing nearby McNeil Point – just off to the right in the photo pair, below.

[click here for a large version of this photo pair]

While the landslide and debris flow that it triggered in 2002 did seem to move McNeil Falls somewhat, the most notable change was to produce a twin waterfall – something waterfall hunters (the author included!) prize. However, as the reshaped falls has continued to evolve over the two decades since the event, the two segments have gradually begun to merge into one – or so I thought until I took a closer look for this article.

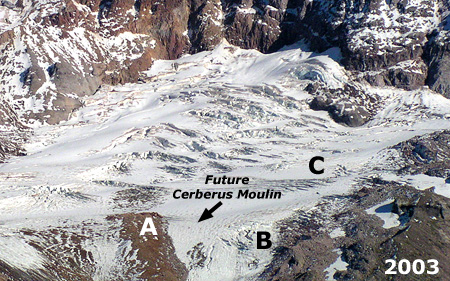

In the following photo pair, you can see that the Muddy Fork has actually been carving away debris from the sloped bedrock, and simply moved the falls northward and down the cliff scarp. You can see the shift by matching the rocks marked “A” on the right, the dark notch to the left of the letter “B” and the protruding rock marked “C” that – surprisingly – used to divide the two tiers of the falls! Today, the south (right) tier of the semi-twin drop is really the original north tier, and a completely new tier has formed to the left of this original tier where landslide debris was cleared from the rock ledge.

[click here for a large version of this photo pair]

Look closely at the above photo pair and you can also see some very large boulders perched to the left of the falls as they existed in 2003. These have since been eroded away, and contributed to the pile of rock debris that has accumulated at the base of the falls in the 2023 photo –shortening the falls a bit.

What will the future bring for McNeil Falls? My guess is that it will continue to shift north a bit more, likely becoming a single tier – twin waterfalls are rare! But even as it find its way to a lower brink along that cliff scarp, the stream will also gradually move loose rock away from the base of the falls as the canyon walls stabilize, so it might become taller over time. There are other examples of exactly this phenomenon on other big waterfalls around Mount Hood – most notably, Stranahan Falls, on the Eliot Branch, which has gained at least 30 feet in height from an eroding canyon floor at its base. Of course, McNeil Falls will also continue to suffer the brunt of the Muddy Fork’s volatile nature and keep changing and reinventing for centuries (and millennia) to come.

Downstream from the falls, the bed of the Muddy Fork continues to gradually collect new debris as the channel carved in the years immediately after the debris flow continues to fill. This can be seen in the photo pair (below), where large boulders now fill the floor of the new channel – and even support young alder and willow pioneers on small midstream islands.

[click here for a large version of this photo pair]

The downstream effects of the 2002 debris flow on the Muddy Fork were less dramatic, yet still reshaped the way the river flows through its valley. This view of the valley (below) from Bald Mountain is roughly two miles below the source of the debris flow. The large rock and gravel deposits along the stream are still plainly visible twenty years later, though the bright green alder and willow colonies have begun to reforest the flooded area. In this view, you can also see the bleached ghost trees along both sides of the stream that were killed by the debris flow.

Though riparian trees like Sitka alder and willows are making inroads, the Muddy Fork continues to meander across the debris flow where the valley is less steep and the stream less channeled

These disturbed areas now serve as important habitat for raptors and cavity-nesting birds alike, along with many other species that require standing skeleton trees to survive. The dense new riparian growth (below) is equally important to many species that require streamside habitat. While major events like the 2002 debris flow might be shocking for us, it’s also a reminder that violent processes like this are built into the cycle of the ecosystem – they are required for the species who have adapted over millennia to forests that continually cycle through disruption and recovery.

Large areas of the debris flow have recovered further downstream from the event, marked by the bright green stands of alder, willow and cottonwood along the Muddy Fork in this view from Bald Mountain

Debris flow pioneers

Whether from fire, debris flow or even human-caused events like logging, watching our forests recover and rebuild provides invaluable insight into the role individual species play in the health of forests. Where we used to value our forests mostly for the lumber that could be harvested (and therefore, mostly for big conifers) we now know that non-commercial species like alder, willow and cottonwood are as essential to forest health as the conifers.

Twenty years into the recovery, I expected to find Sitka alder (below) dominating the young forests returning to the debris flow, as these tough, adaptable trees among the first to reclaim disturbed ground wherever it might occur. They are often called “slide alder” for their ability to survive in avalanche chutes, as they freely bend and give under the heaviest of winter snow loads, often popping new leads from horizontal, snowpack-flattened limbs. But alders have a super-power that is especially important in forest recovery: they are nitrogen fixers that enrich the soil as they grow, making them uniquely suited as pioneers in disturbed areas.

Sitka alder growing on the Muddy Fork debris flow

What I didn’t expect to find in the recovering forest atop the debris flow were Black cottonwood (below). Yet, many are thriving throughout the alder thickets, outpacing the alders since they can easily grow to 50-60 feet in mountain environments compared to just 30-40 feet for alders. Cottonwood are fast growers, too, especially where they can tap into a steady supply of groundwater – something the shallow water table in the Muddy Fork valley provides in abundance. They are important wildlife trees, too, including the browse they provide as young trees and the nesting cavities that form in the trunks of older trees as they mature.

Cottonwood growing on the Muddy Fork debris flow

An even more startling pioneer in the recovering forest on the debris flow are Douglas fir (below). These trees don’t require much of an introduction — as our state tree and a species found all over Oregon. I didn’t expect to find so many here, in part because we’ve been conditioned by the timber industry to believe these native conifers must be hand-planted after logging, and then only after all other vegetation that might compete has been killed with herbicides.

Douglas fir growing on the Muddy Fork debris flow

Douglas fir are fast growers, and with their early arrival as pioneers in the new forests along the Muddy Fork, there’s a good chance they will keep pace with both the alders and cottonwood and quickly begin to restore a conifer overstory – though “quick” is measured in decades and centuries when describing forest recovery!

Douglas maple growing on the Muddy Fork debris flow

Another surprise in the new forest growing on the debris flow is Douglas maple (above), a close cousin to our Vine maple, and sometimes called Rocky Mountain maple. These attractive trees are sprinkled throughout the young trees returning to the Muddy Fork and they are positioned to become part of the future understory of a mature conifer stand. Where alder and cottonwood are eventually shaded out by taller conifers, Douglas maple are more tolerant of shade, and can coexist with the big trees. They are also more drought-tolerant than their Vine maple cousins, and thus well-suited to the sandy upper layers of the debris flow that can become quite dry during summer droughts.

The cycle continues… except faster, now

Just as the recent series of wildfires in WyEast country have given us the gift of insight into how a forest regenerates after a burn, the debris flow on the Muddy Fork is providing a glimpse into the resilience of Mount Hood’s forests in the face of growing disturbances from climate-driven floods, landslides and debris flows. There is no way to know if the 2002 landslide in the Muddy Fork canyon was triggered by climate change, yet scientists do know that extreme rain events and unusually saturated soils are increasingly triggering such events. And while these events have always occurred, the extreme and often erratic nature of our storms in recent years has accelerated the pace and scale of flooding and debris-flow events on the mountain. The good news from the Muddy Fork is that our forests are – so far – coping well with these changes, especially in riparian areas where the restored habitat is most critical.

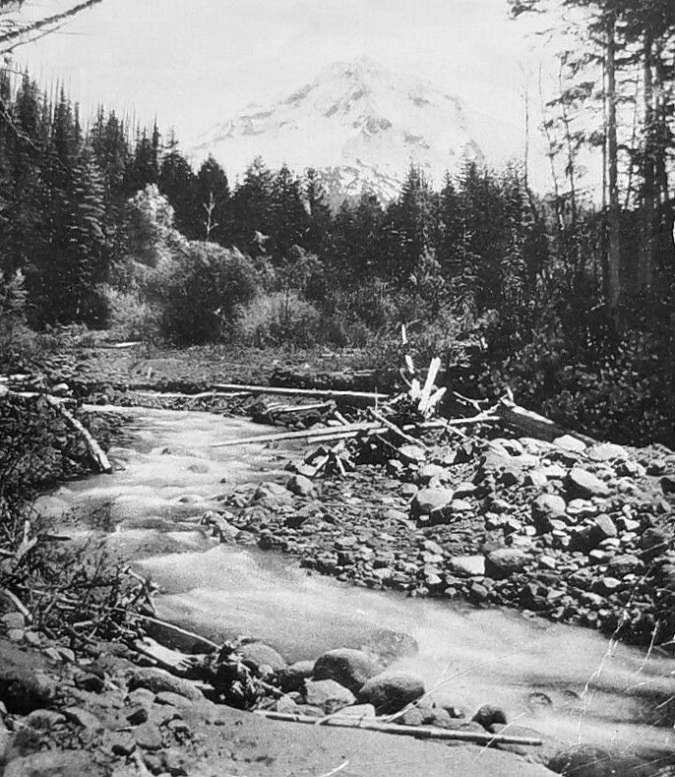

Early 1900s scene along the upper Sandy River

Historic images and geologic evidence show these events to be part of a timeless cycle of destruction and rebirth. This image (above) show the upper Sandy River valley in the early 1900s, with mix of debris and young streamside vegetation (the willows and alders toward the background) that look much like today’s conditions. Clearly, periodic floods and debris flow events had always played a role, here.

This image (below) is a wider, hand-tinted view from about 1900 that shows the Muddy Fork branch of the Sandy River hugging the left side of the valley, with obvious signs of flooding and debris flows. There’s a story in the young forests covering the balance of the flat Sandy River valley floor, too (known as Old Maid Flat) in this view: at the time the photo was taken, just over a century had elapsed since the Old Maid eruptions on Mount Hood covered this entire valley with a debris flow that extended 50 miles downstream to the Columbia River, creating today’s Sandy River Delta. This very early view also shows burn scars (colorized as white snow) around the western foot of the mountain that have long-since recovered, and are now covered with dense forests of Noble fir.

The Muddy Fork is the open channel on the left in this colorized view of the Sandy River Valley from about 1900

While these events may seem random and jarring in from the perspective of a human lifetime, when you connect the dots between events over geologic time, the continuum is that of a mountain in a perpetual state of both eroding and occasionally rebuilding itself, one catastrophic event after another.

It is this long view that helps us understand and appreciate how our forests have evolved not to a specific end-state (the view from a logging perspective), but instead, have evolved to continually adapt to their conditions in a perpetual state of renewal and rebirth. The fact that our forests are rebounding so readily in places like the Muddy Fork or the scorched slopes of the Gorge fire — even now, in the midst of climate change – is both inspiring and reassuring in a time of unprecedented change in the world around us.