Each year since 2004 I’ve published a wall calendar dedicated to the special places that make Mount Hood and the Gorge a national treasure — and of national park caliber! You can pick one up for $30 at the Mount Hood National Park Campaign store at CafePress, and you’ll also be supporting the campaign website and this blog when you do!

The following is a preview of the calendar images I picked for the 2015 edition, along with some backstory behind the photos. All of the photos were taken from November 2013 through October 2014. Part of the challenge each year is to come up with 13 new calendar-worthy images, which in turn ensures that I get out on the trail and poke around my favorite haunts, plus a few new spots whenever I can!

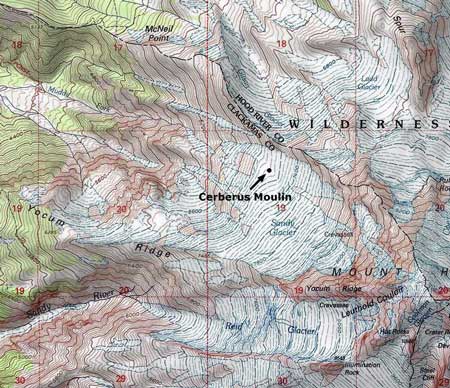

For January, I picked a close-up view of the upper Sandy Glacier and the towering cliffs of the Sandy Headwall. This view came from an early snowfall last winter, one of several trips I made to the Bald Mountain and McGee Ridge:

On one of those trips to the McGee Ridge viewpoint, I had just set up my camera and tripod along the Timberline Trail when a pair of climbers came down from the mountain. They were obviously not typical hikers, and soon I realized that they were the explorers I had just written a blog article about! “Sandy Glacier Caves: Realm of the Snow Dragon!” was written partly in anticipation of the Oregon Field Guide 2013 premiere episode that featured the glacier Caves… and my new trail acquaintances, Brent McGregor and Eric Guth.

Brent and Eric pointed out several features around the glacier caves from our vantage point. I was later able to add a postscript to the original article to elaborate on some of the new details about their discovery that I learned that day on the trail.

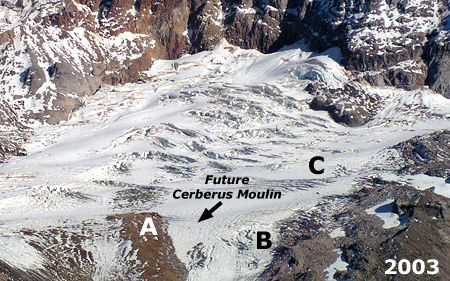

I’ve also been able to help Brent with his historic research on the formation of the glacier caves with a series of images I’d taken of the Sandy Glacier since the early 2000s. I’ve photographed the glacier in detail pretty much every year for more than a decade, mostly because of it’s scenic beauty, so it was great to discover a more practical use for all those photos!

For February, I picked a photo from a memorable winter day on Mount Defiance (below) after a bank of freezing fog had settled in on the mountain for several days. Nearly every surface was covered with long, beautifully developed ice crystals that had grown undisturbed in the almost still air of the freezing fog layer.

On that frosty day, I also stopped to photograph the sign shown below on the way up to Mount Defiance, as it showed amazing insight and precision by the Hood River County road department in deciding where to stop plowing!

For March, I picked a scene from the Pacific Crest Trail where it climbs along the west rim of the White River canyon. This section of trail is also part of the Timberline Trail, and is surprisingly overlooked, given the views and close proximity to Timberline Lodge.

I posted an article in 2011 on the buried forests that can be seen here. The deeply carved maze of ravines that make up the White River canyon are cut into volcanic debris from the Old Maid eruptions that occurred from 1760 to 1810, and subsequent erosion has revealed some of the well-preserved trees that were buried in these eruptions. The 2011 article describes how to view these old specimens.

I also enjoyed watching a lenticular cloud form over the mountain in the hour or two that I sat on the canyon rim that evening last winter — one of my favorite mountain phenomena. You can see just the beginning of the cloud over the summit in the calendar view, and the tiny sliver later blossomed into the classic lenticular cloud shown in the view below, as I was packing up for the day:

Lenticular clouds typically form when moist air from approaching weather fronts is compressed as it passes over the big volcanoes in the Cascade Range. They often form as much as a day before the cloud bands of a Pacific front actually arrive, so are a useful barometer of changing conditions.

For April, I picked something a little different: a desert scene just a few miles east of the mountain, where the same White River that originates from its namesake glacier in the previous scene flows east into the rugged rimrock country of Oregon’s High Desert, shown below:

Over the millennia, the White River has carved through many layers of Columbia River basalt to form its desert canyon, but as it approaches the confluence with the Deschutes, the river encounters an especially tough series of basalt layers. The result is the spectacular White River Falls, a misty green emerald in the desert, protected in a small state park.

The lower falls pictured in the April image is about one-half mile downstream from the main falls, and well off the popular trail in the area. The calendar image is actually just a cropped portion of a very wide panorama (below) that captures more of the rugged scene at the lower falls.

The scoured bedrock in the foreground of this view is testament to volatile nature of the White River: seasonal floods regularly surge to this depth, engulfing the floor of the canyon.

In another 2011 article titled “Close Call at White River Falls”, I described the threats to this magnificent area, and why it deserved better protection — perhaps someday a unit of Mount Hood National Park?

In addition to the natural scenery, the canyon is home to the fascinating ruins of an early 1900s hydroelectric plant. Desert weather has helped preserve the many relics in the area, but arid conditions haven’t prevented vandals from taking an increasing toll on priceless historic resources.

Hopefully, we can someday stabilize the White River Falls site and preserve the remaining traces of history for future generations to explore.

For May, I chose another unusual image for a Mount Hood National Park calendar: Middle North Falls on Silver Creek. Why? Mostly because what we now know as Silver Falls State Park was once proposed to become a national park in the 1920s! It would have been a terrific addition. The scenery, alone blows away many of the existing national parks monuments in our park system!

Alas, the national park proposal failed after a National Park Service study deemed the logged-over landscape of the 1920s too ravaged to be worthy of park status. Thankfully, that didn’t stop the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s from building the elaborate, magnificent trail system and beautiful South Falls Lodge (listed on the National Historic Register in 1983) that we still enjoy today.

The national park idea for Silver Falls resurfaced again in 2008, when Oregon State Senator (then Representative) Fred Girod proposed it during a special session. Notably, Dr. Girod is a Republican from Stayton, representing the Senate district that encompasses Silver Falls State Park, so maybe we’ll see the idea resurrected in the future? I like that maverick thinking, Senator!

On the visit last spring when I photographed Middle North Falls, I was reminded that Oregon’s state parks do a pretty good job of embracing the national park tradition at Silver Creek when a young ranger appeared, leading a group of youngsters on a day hike. Kudos to Oregon Parks and Recreation Department for providing programs like these!

Could Silver Falls State Park become a unit of a future Mount Hood National Park? Why not! One tangible benefit would be the opportunity to expand the footprint from the current park boundaries to include the rest of the upper watershed of Silver Creek. The park more than doubled in size in 1958, when a federally funded expansion added in a portion of the headwaters, bringing the park to the present size of just over 90,000 areas.

Yet, heavy logging and large private inholdings upstream continue to impact Silver Creek stream with silt and algae blooms. These impacts could easily be reversed if the upper watershed were managed for conservation and recreation, instead — especially if the park were expanded to include the upper watershed and its associated habitat.

For June, I picked an image of Butte Creek Falls, a nearby cousin to Silver Creek located even closer to Mount Hood, within the Santiam State Forest. Like Silver Creek, the upper watershed of Butte Creek is heavily logged, with some obvious sediment and algae in the stream as a result.

Also like Silver Creek, the health of Butte Creek could be turned around with a shift to managing for conservation and recreation. Unlike Silver Creek, most of the lands in the upstream watershed are already held in the public trust by the State of Oregon.

Unfortunately, our state forests are held captive by a legislature determined to log them to feed the state general fund — and to ensure that rural counties that already pay only a fraction of the property taxes levied in other parts of Oregon aren’t inconvenienced with paying for their own schools.

Therefore, the best way to restore Butte Creek would be to transfer it to Oregon Parks and Recreation Department as a very large state park… or incorporate it into a future Mount Hood National Park! At a minimum, it’s time for the Santiam State forest to focus on restoring forests and protecting watersheds, not just future timber sales.

The behind-the-scenes, somewhat embarrassing story that goes with the Butte Creek Falls image is one of my hiking buddy Jamie Chabot helping change a flat tire after our trip to Butte Creek and nearby Abiqua Falls. We managed to take a couple of wrong turns in the maze of logging roads and clearcuts that surround the small preserve containing Butte Creek: at some point, I jumped out to survey the canyon below to figure out where we went wrong… only to hear a HISSSSSSS coming from one of the rear tires!

There was no room to pull off to the side, so we were in the awkward predicament of having the car up on a jack in the middle of an active logging road. Fortunately, we were able to install the spare before a loaded log truck came barreling our way! My belated apologies to Jamie for doing the heavy work while I took pictures… but somebody had to document the episode for posterity!

Jamie was also my hiking companion on a couple of trips to Owl Point last summer. This has been an annual favorite of mine since a group of volunteers from the Portland Hikers forum rescued the Old Vista Ridge from being lost to official Forest Service neglect in 2007.

Each year, the trail seems to get better, thanks to a lot of unofficial TLC from anonymous trail tenders. Today, the Old Vista Ridge trail is in great shape and now forms the boundary of the expanded Mount Hood Wilderness, so in that sense has been etched into legal permanence. Hopefully, it will eventually make it back onto the Forest Service inventory of officially maintained trails, a status it clearly deserves.

There are now several geocaches and a trail log tucked along the historic old trail, and it’s amazing to see how busy the area has become now that it has been featured in several popular hiking guides (including Williams Sullivan’s “100 Hikes in Northwest Oregon” and Paul Gerald’s “60 Hikes within 60 Miles of Portland”).

One trail log had more than 60 entries for just 2014, including this wonderful entry from a young family introducing their kids to the adventures of hiking and exploring the Mount Hood backcountry at a very young age:

One of my favorite experiences on the trail is seeing young families introducing their junior hikers to our public lands, battered field guides in hand. Just like my own formative experiences just a few decades ago.

For August, I picked an image from another of my favorite spots, just off the Cooper Spur trail, above the lower extent of the Eliot Glacier. This image was taken on one of those days when clouds were wrapped around the mountain for much of the day, but suddenly cleared for a few minutes — just long enough to capture a few photos before the mountain disappeared, once again:

I certainly do not mind sitting on the shoulder of the mountain waiting out the clouds (there’s no such thing as a bad day on the mountain, after all!), but a bonus during this wait was learning a new bird species (to me), as a pair of these small birds (below) stopped by to check me out:

This is a horned lark, a wintertime migrant to our area, and the pair I saw had likely arrived recently when I spotted them last August. The Portland area actually has a year-round resident population of streaked horned larks, which look similar to horned larks and are a threatened species. These are details I learned after the trip from the helpful folks at the Portland Audubon Society.

According to Audubon staff, horned Larks are widespread songbirds of fields, deserts, and tundra, where they forage for seeds and insects, and sing a high, tinkling song — and thus were quite at home in the tundra conditions of Mount Hood’s high east side. Though they are considered common, they have undergone a sharp decline in the last half-century. Their very generalized range map shows them wintering from the Cascades west and breeding in summer in Canada tundra/steppe terrain.

For September I picked an image from Wyeast Basin, taken toward the end of a lovely early autumn day as a family and their dog ambled across the sprawling meadow. Wyeast Basin is remarkable for the surprising number of springs bubbling up from the mountain slopes and racing one another downhill, often just a few feet apart.

While this view (above) from the calendar is the familiar scene at WyEast Basin, I also turned my tripod around to capture the web of springs and streamlets flowing north toward the big Washington volcanoes, on the distant horizon. The talus slopes of Owl Point can also be seen in the distance from here, just above the tree line.

For October, the scene is from Elk Meadows, perhaps the most photogenic of the string of alpine meadows on Mount Hood’s rugged north side. In this view, the Coe Glacier tumbles below the summit, and 7,853-foot Barrett Spur looms darkly on the left. Avalanches roll off Barrett Spur in winter, sometimes with devastating effect on the alpine forests below, as the many bleached snags and stumps in Elk Cove suggest.

My companions for the Elk Cove hike this fall were Jamie Chabot and Jeff Statt. I met both when Trailkeepers of Oregon (TKO) was founded in 2007: Jeff was the founding president of the new non-profit, and Jamie the original creative force behind the TKO logo, Portland Hikers calendars and the TKO web identity.

Both Jeff and Jamie continue to support TKO after all these years as the organization continues to grow, and we still meet up for periodic trail stewardship projects together. I’m honored to have them as trail friends, and having them along on this hike made it extra-special!

For November, I picked a familiar view of Triple Falls on Oneonta Creek, taken during an especially wet week in the Gorge. Normally, the somewhat muddy runoff in this scene would be a deal-killer for photos, but I came around to the idea that in this case, it told the story of swollen Cascade streams during the stormy months of late autumn rather nicely, so added it to the mix.

I was memorably soaked on the hike to Triple Falls, not because rain is particularly unique in the Gorge, but because I had just re-ducked my trusty canvas hat (for waterproofing)… but had left it drying in the oven, at home! I discovered this fact at the Oneonta trailhead, so circled back to the Multhnomah Falls lodge to see what sort of hats were in stock.

It turns out that baseball caps are the ONLY option at the Multnomah Falls lodge — and I HATE baseball caps! (primarily because they don’t fit all that well on my basketball-sized head..!) Well, at least I could support my alma mater, and I hit the trail $20 poorer with a ridiculous, ill-fitting beanie that (sort of) kept my large, bald head dry…

Once on the trail, I also ran across one of the most extensive landslides to form in recent years, cutting away a 100-foot swath of the Oneonta Trail along a steep canyon section. Trail crews had constructed a temporary crossing of the slide, but just a few days after that trip in November, the slide claimed more ground, erasing the temporary trail. Such is the ongoing challenge of keeping trails open in the very active landscapes of the Gorge and Mount Hood!

For December, I picked a late fall image of Elowah Falls, taken from one of the long-bypassed viewpoints along the original Civilian Conservation Corps route described in this recent article on McCord Creek.

Photographing a 213′ waterfall at close range means a wide-angle lens and blending some images. In this case, I merged three vertical images taken with my 11mm lens to create the panoramic view. This is my first time photographing from this spot, and I will definitely return!

By now you’ve been introduced to my trail buddy Jamie, and on the way out from Elowah Falls that day I ran into Jamie and his two boys! They were headed toward the upper falls on McCord Creek on that very busy hiking day in the Gorge. It was great to see Jamie passing on the hiking tradition to boys!

That’s it for the 2015 Mount Hood National Park Campaign calendar highlights, and now for a few thoughts on the blog…

Thanks for another year!

I launched the WyEast Blog in 2008 as a simpler way to promote Mount Hood and the Gorge as “national park-worthy” than updates to the project website would allow. And though I didn’t post quite as often this year for a whole variety of reasons (mostly, real life getting in the way), I was amazed to see the readership for the WyEast Blog continue to grow in 2014.

In early 2014, the monthly page views edged above the 5,000 mark for the first time, and jumped well above that mark during the peak hiking months of spring and summer. More importantly, the list of official blog followers has grown steadily to 141 this year. These are the true Mount Hood and Gorge junkies that I have in mind when I post to the blog, and these are also the folks who send me both nice notes and periodic corrections — both are greatly appreciated!

I posted a total of 14 articles this year, down a bit from previous years, but bringing the six-year total to 136 articles. I’ve also got a bunch of new articles in the oven, ready to post when time allows. So, the WyEast Blog will be around for awhile!

The two most popular articles continue to be:

10 Common Poison Oak Myths (2012)

Ticks! Ticks! (10 common myths) (2013)

The “ticks” article has been viewed 38,147 times since I posted it in 2013, and the poison oak piece 21,545 times — sort of amazing! But these numbers have validated my obsession with providing thorough, detailed, geek-worthy articles that are more in the magazine format than typical blog fare.

So, enough facts, figures and anecdotes: if you’ve read this far in my annual, somewhat (ahem!) self-indulgent post, THANK YOU for being a reader… and most importantly, thanks for being a friend of Mount Hood and the Gorge!

See you on the trail in 2015!

Tom Kloster

WyEast Blog