Oregon Public Broadcasting’s venerable Oregon Field Guide series kicks off it’s 25th season in October with a remarkable story on the hidden network of glacier caves that have formed under the Sandy Glacier, high on Mount Hood’s west flank.

In the video preview (below), Oregon Field Guide executive producer Steve Amen says that “in the 25 years we’ve been doing Oregon Field Guide, this is the biggest geologic story that we have ever done”. This is bold statement from a program that has confronted all manner of danger in documenting Oregon’s secret places!

Glacier caves are formed by melt water seeping through glaciers and flowing along the bedrock beneath glaciers. Over time, intricate networks of braided tunnels can form. Because a glacier is, by definition, a river of moving ice, exploring a glacier cave is inherently dangerous — and this is what makes the upcoming Oregon Field Guide special so ambitious.

Cave explorers have been actively exploring and mapping the extent of the Sandy Glacier caves for the past three years. This previously unknown network of caves has been dubbed the Snow Dragon Glacier Cave System by cavers Eduardo Cartaya, Scott Linn and Brent McGregor in July 2011. Cavers have since surveyed (to date) well over a mile of caves in the network, with parts of the cave system nearly 1,000 feet deep.

Ice Cave or Glacier Cave? Here in volcano country, it’s worth noting that a glacier cave is different than an ice cave. Where a glacier cave has roof of glacial ice, an ice cave occurs where persistent ice forms inside an underground, rock cave. In the Pacific Northwest, we have several examples where ice has accumulated inside lava tubes to form true ice caves, such as the Guler Ice Cave near Mount Adams and Sawyer’s Ice Cave in Central Oregon.

To date, the Snow Dragon cave network consists of three caves that intersect, dubbed the Snow Dragon, Frozen Minotaur, and Pure Imagination caves. Within these caves explorers have discovered a fantastic landscape of streams and waterfalls flowing under a massive, sculpted ceiling of ice.

The caves are punctuated by moulins (pronounced “MOO-lawn”), or vertical shafts in the ice formed by meltwater. Some of these moulins are dry, some are still flowing, and a few have have grown to become skylights large enough serve as entry points into the cave system for daring explorers.

Caving expeditions to the Sandy Glacier caves by the National Speleological Society (NSS) in 2011 and 2012 were featured in the February 2013 NSS News, with a dramatic photo of colossal moulin on its cover. These volunteer expeditions included NSS geologists, glaciologists, spelunkers, scuba divers and mountain climbers who spent eight days documenting the cave system from a base camp high atop the Sandy Glacier.

According to the NSS explorers, the Snow Dragon cave complex is the largest ice cave complex in the lower forty-eight states, and one of the largest in the world. To date, these explorers have found icy passages ranging from huge, ballroom-sized open spaces with 40-foot ceilings to narrow, flooded crawl sapces only a few feet high, and passable only with diving gear.

The Oregon High Desert Grotto, an affiliate of the NSS, has posted a series of fascinating maps documenting their explorations on their website.

The Story Behind the Sandy Glacier Caves?

Glacier caves typically form near the snout of a glacier, and explorers simply follow the outflow stream into the cave system. Such was the case with Paradise Ice Caves at Mount Rainier (now disappeared) at the terminus of the Paradise Glacier. More recently, hikers have explored the outflow opening at the Sandy Glacier, as well.

The Snow Dragon caves under the Sandy Glacier are different, however. While the glacier does have an outflow opening to the cave system, the cave network extends far beyond the terminus of the glacier, apparently reaching almost to the headwall, nearly a mile away and almost 2,500 feet above the terminus in elevation. The scale and scope of these caves seems to be partly the result of the glacier shrinking, and not just the effects of melting near the terminus of the glacier.

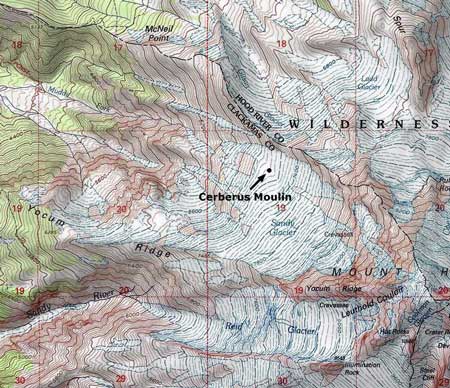

This broader phenomenon first became apparent when a huge moulin — known informally to many hikers as the “glory hole” and formally named the Cerberus Moulin by cavers — appeared in the glacier a few years ago. The Cerberus Moulin is plainly visible to hikers from nearby McNeil Point, which also serves as the jump-off point for explorers.

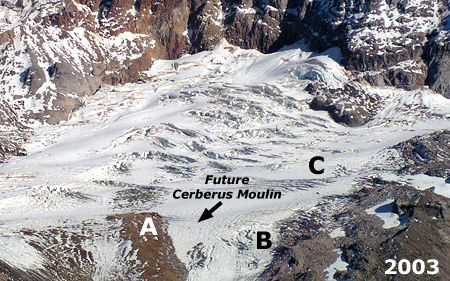

The following photos of the Sandy Glacier were taken nine years apart, in 2003 and 2012, and show the startling retreat of the glacier over just the past decade. The Cerberus Moulin had not yet formed in the 2003 photo, but is plainly visible in the 2012 image. For reference, the broad moraine to the left of the Cerberus Moulin is labeled as (A) in the photos:

The photo comparison shows big changes in the activity of the glacier, too. What was once an icefall near the terminus of the glacier (B) in 2003 has since receded to the point that the rock outcrop that was beneath (and formed) the icefall is now exposed in the 2012 image. Likewise, the lower third of the glacier (C) was clearly crevassed and actively moving in the 2003 image compared to the 2012 image, where an absence of crevasses shows little glacial movement occurring today in this section of the glacier.

The rapidly shrinking glacier could be an explanation for the relative stability and remarkable extent of the caves underneath the ice. The increased melting is sending more runoff through and under the glacier, helping to form new moulins feeding into the ice caves.

The slowing movement of the lower portion of the glacier could also help explain why the cave network has become so extensive, as more actively flowing ice would be more likely to destroy fragile ice caves before they could become so extensive and interconnected.

Part of a Larger Story

The Sandy Glacier Caves discovery is really part of the much larger story of Mount Hood’s rapidly shrinking glaciers. After millennia of relative stability, we are witnessing broader changes to the landscape surrounding in response to the retreat of the glacial ice.

The downstream effects in recent years from Mount Hood’s melting glaciers have been startling, and the Sandy Glacier is no exception. Sometime during the winter of 2002-03, a massive debris flow was unleashed from just below the terminus of the Sandy Glacier, and roared down the Muddy Fork canyon. The wall of mud and rock swept away whole forests in its wake, burying a quarter mile-wide swath in as much as fifty feet of debris.

The view (above) looking across the 2002-03 Muddy Fork debris flow shows toppled trees at the margins, while the forests in the main path of the flow were simply carried away.

The view downstream (below) from the center of the debris flow shows the scope of the destruction, with the debris at least 50 feet deep in this spot where the Timberline Trail crosses the Muddy Fork.

The Muddy Fork has only recently carved its way down through the 2002-03 debris to the original valley floor, revealing mummified stumps from the old forest and visible giving scale to the scope of the event (below).

Seven years after the 2002-03 flow, the Muddy Fork had cut a channel down to its original elevation, revealing the full depth of the flow.

These stumps of trees snapped off by the 2002-03 debris flow have reappeared where the Muddy Fork has carved down to the original river level.

With no way to know how long Mount Hood’s glaciers will continue to retreat, catastrophic events of this kind will recur in the coming decades. Runoff from the retreating glaciers will continue to carve away at newly exposed terrain once covered by ice, with periodic debris flows occurring as routine events.

In November 2006, another major flood event in the Sandy River canyon caused damage even further downstream, in the Brightwood area, where private homes line the Sandy River:

Damage from the 2006 flood was still being repaired when yet another major storm burst stormed down the valley in January 2011. During this event, a large section of Lolo Pass road briefly becoming part of the Sandy River, and scores of homes were cut off from emergency responders:

The 2011 event washed out the south approach to the Old Maid Flat Bridge over the Sandy River, forcing the Forest Service to jury-rig a temporary ramp to the bridge. The entire crossing has since been replaced, but like all repairs to streamside roads around the mountain, there is no reason to assume that another event won’t eventually destroy the new bridge, too.

The Old Maid Flat Bridge over the Sandy River was repaired with a temporary approach ramp (on the right in this photo) where the bridge approach had washed out by raging water

This wider view shows the rebuilt section of Lolo Pass Road that was briefly a channel of the Sandy River during the January 2011 flood

Similar events have occurred over the past several years on the White River, Ladd Creek, East Fork Hood River and the Middle Fork Hood River. The predicted climate changes driving these events give every indication that we will continue to watch similar dramatic changes unfold around Mount Hood in decades to come.

During the 2006 debris flows, the old White River Bridge was completely inundated, leaving an eight-foot layer of boulders on the bridge (ODOT)

By late 2012, the Federal Highway Administration had built a new, much larger bridge over the White River designed to survive future debris flows

Just as the wildfires that burned through forests on the eastern and northern flanks of Mount Hood over the past few years have given us new insights into the cycle of forest renewal, the unfolding geological events linked to changing glaciers provide a similar opportunity to better understand these natural processes, too.

While these destructive events are tragic to our sentimental eyes, the rebirth of a forest ecosystem is truly remarkable to witness — as is the discovery of the Sandy Glacier ice caves in the midst of the larger decline of Mount Hood’s glaciers. All of these sweeping events are reminders that we’re just temporary spectators to ancient natural forces forever at work in shaping “our” mountain and its astoundingly complex ecosystems.

So, stay tuned and enjoy, this show is to be continued!

_________________________

OPB Airing Dates

Here are the broadcast dates for the Oregon Field Guide premiere:

• Thursday, October 10 at 8:30 p.m. on OPB TV

• Sunday, October 13 at 1:30 a.m. on OPB TV

• Sunday, October 13 at 6:30 p.m. on OPB TV

For fans of the show, a 25th Anniversary retrospective will also be airing on Thursday, October 3rd. You can learn more about OFG and view their video archive on their website.

_________________________

October 4th Postscript

In the small world department, I had the honor of meeting epic caver, climber and photographer extraordinaire Brent McGregor on the Timberline Trail this afternoon. He and caving partner Eric Guth had spent the night near the entrance to the Snow Dragon Glacier Cave!

After learning a LOT more about the Snow Dragon cave complex from Brent today (and having my jaw drop repeatedly as I heard about their exploits under the glacier!), I’ve updated the above article — including the more accurate use of the name Cerberus Moulin in lieu of the generic “glory hole” nickname that some hikers have been using.

Brent also pointed me to a couple fascinating new videos from OPB that just add to the anticipation of the Glacier Caves premiere on OPB:

Behind the Scenes of Glacier Caves: Mt. Hood’s Secret World

Special Glacier Caves website from OPB

And finally, one more link: the Glacier Caves OPB documentary will be screened in a free, special preview on October 9th at the Hollywood Theater. Here’s the link to the event Facebook page:

Thanks for the terrific conversation, Brent – great meeting you and Eric!