Editors note: periodically, I feature local artists and writers in this blog. Brian Chambers is a local photographer in Hood River who has been capturing stunning images of Mount Hood and the Columbia River Gorge. Here’s a recent conversation with Brian.

Brian has also offered to donate a portion of any sales resulting from this interview to the Friends of the Gorge, Trailkeepers of Oregon (TKO) and the Columbia Land Trust, so be sure to mention the blog if you purchase Brian’s photos! (more info following the interview)

_______________

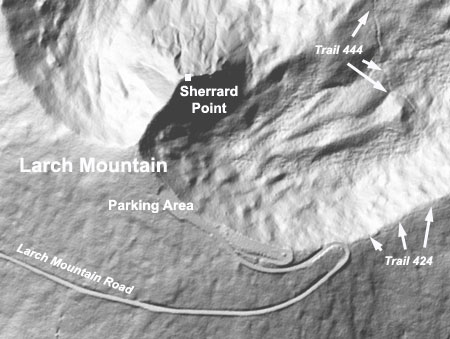

WyEast Blog: Great to meet you, Brian! How long have you been shooting landscape photography in the area?

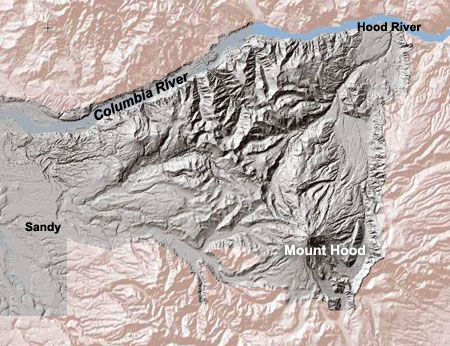

Brian Chambers: I first came to Hood River on vacation in 1996. I immediately fell in love with the place and had moved here within one year. That was back in the old days of film. I had done a ton of photography way back in high school and had my own darkroom but did less and less as I got older. I was doing a little bit of photography when I moved here but it wasn’t until I bought my first DSLR in 2008 that my hobby became a full-blown addiction.

Mount Hood from the Eastern Gorge

(click here to view a large version in Brian’s gallery)

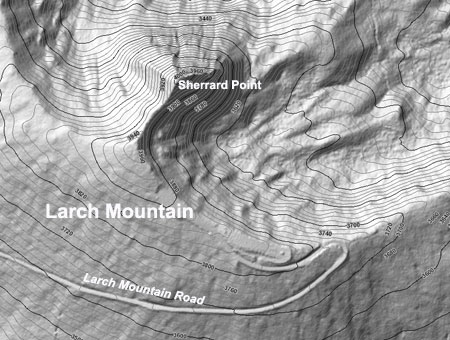

WyEast: What are your favorite Gorge locations for shooting – the ones you go back over and again?

Brian: It changes so much from year to year. I tend to find a new location and maybe pre-visualize some images in my mind. I will go back over and over until I am satisfied with the images I can capture with my camera. I will keep trying until I get that special combination of light and composition that really matches what I had seen in my mind.

The thing I like the most about the gorge is the variety. If I had the energy I could shoot a fresh snow fall on a mountain stream at sunrise, at lunch take on moss covered waterfall, at sunset capture the most amazing wildflower scene, and a midnight capture an abandoned house in the middle of a wheat field. I really feel the options are arguably the best in the country.

Upper Hood River Valley orchards at sunrise

(click here to view a large version in Brian’s gallery)

Some of my favorites include shooting the orchards of Hood River, Hood River itself with the river in the foreground and the mountain behind it, the view down the gorge anywhere there is exciting light from places like Rowena, Underwood viewpoint, Mitchell point. I have been heading to some of the more off-trail waterfalls and really enjoying the exploring aspect of that. I love Mt Adams in the fall for the color. I could go on all day.

Early in the spring I am really drawn to the east hills. A few years ago it was the Rowena crest, then it was Dalles Mountain, then it was the Memaloose Hills Hike area.

Sunrise a Rowena Crest

(click here to view a large version in Brian’s gallery)

WyEast: What makes those locations special?

Brian: One big factor is the flowers. Especially this year, although it was an early bloom, it was off the charts good. I don’t think I have ever seen it that good. I love the openness of the land, being able to see the light interacting with terrain. The different compositional options, with 360 degree views and the amazing mountain and gorge views in the background. Sitting in a field of wildflowers all alone watching the rising sun dancing with Mount Hood and lighting up the flowers. It doesn’t get much better than that.

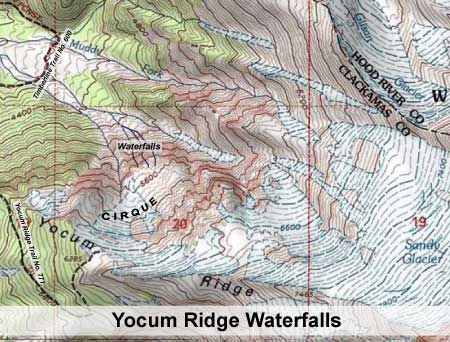

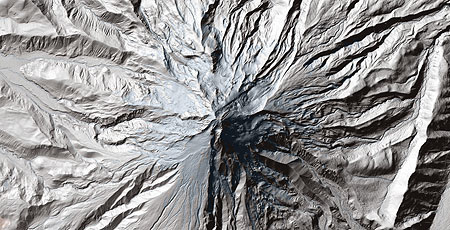

WyEast: What about your favorite Mount Hood locations?

Brian: Well in the winter I spent a ton of time snowshoeing up the White River. It has such an easy access to an amazing mountain view with the river in the foreground. I am almost embarrassed to say how many times I have gone up there looking for the perfect light. I finally got a couple of images I am pretty happy with this year. Persistence can pay off.

Sunrise on Mount Hood and the White River

(click here to view a large version in Brian’s gallery)

In the summer I often am heading up to the WyEast Basin and Cairn Basin area. I like that you can take several different trails to get there and it is this wonderful mix of high alpine, lush wildflowers, refreshing streams and small waterfalls with some of the best close-up views of the mountain. The number of great subjects in such a small area is almost mind-boggling.

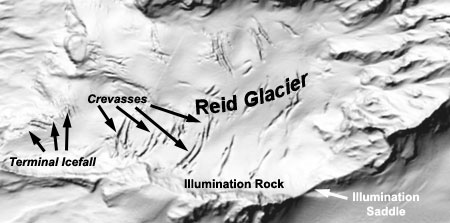

WyEast: Some of your most stunning photos are shot during the golden hours of early morning or evening – do you have any tips for shooting in those conditions?

Brian: Getting up earlier and staying out later is usually the simplest thing people can do to greatly improve their photography. It is very difficult to get as compelling a photo in the middle of the day. The rapidly changing light around sunrise and sunset can really add a ton of interest, color and excitement to your images. Watch the sky, satellite images and weather forecasts to see if there is going to be enough clouds to make the sky interesting but not too many so that the sun is blocked.

Late afternoon wildflowers near Cairn Basin on Mount Hood

(click here to view a large version in Brian’s gallery)

A tripod is critical for getting clear shots when it is darker. I suggest shooting in RAW not JPEG and bracketing your exposures to capture all of the detail in the brightest and darkest parts of the image.

Be Patient. I can’t tell you the number of times I have been taking pictures and all the other photographers have left and 10 minutes after a boring sunset the sky just lights up.

Autumn sunset at Mount Adams

(click here to view a large version in Brian’s gallery)

That being said, I would be lying if I didn’t say I am just like everyone else in that I sometimes can’t pull myself out of bed in the early morning and I sometimes head to the brewpub at sunset rather than out to shoot. My family is pretty tolerant of me heading out to shoot but I try to balance life and responsibility with photography. Find the balance that makes you happy.

WyEast: You also have some amazing photos that feature the night sky. How exactly do you capture those images?

Brian: It is surprisingly easy if you have a fairly new digital camera. Have a solid tripod. I suggest getting to your location before it gets dark. Set up all your gear, compose your image and focus. Cameras are unable to auto-focus in the dark so you need to focus before it gets too dark and then set your camera to manual focus so it will not try to refocus.

Start taking pictures before it is totally dark and see what happens. Learn how to adjust your camera in manual exposure. Set your aperture to wide open (the smallest number possible), your shutter speed to around 20 or 30 seconds. Crank your ISO up to 800 or 1600 or even higher and fire away. The beauty of digital is it doesn’t hurt to mess up. If it is too dark crank up your ISO higher or lengthen your shutter speed. If it is too bright turn your ISO down. Look at your results and see what works and what doesn’t. Play and have fun.

Milky Way and Mount Hood from below Cooper Spur

(click here to view a large version in Brian’s gallery)

WyEast: Those are great tips! Some of your images of Mount Hood and the Gorge also feature lightning, which seems especially challenging to capture. Other than not standing on high ground – which, actually, it looks like you were – what can you tell us about getting a great lightning photo?

Brian: First of all be safe. I think a lot photographers tell stories of risking life and limb to “get the shot”. Probably not worth it and often just an embellishment to make it sound more dramatic. I like to find a place where I can shoot while sitting in the car or at least find shelter immediately.

Thunderstorm lighting up the East Gorge

(click here to view a large version in Brian’s gallery)

It helps to have a cable release or some other way of triggering your camera like a remote control. That allows you to be safe in the car while the camera is outside. If it is dark and you can use a long exposure you can just set the camera to shoot continuously. Sort of a “spray and pray” method but there is nothing worse than missing that solitary lightning bolt.

If it is daylight, the “spray and pray” method doesn’t work because most cameras get bogged down and stop shooting after 20 seconds or so. In that case you can just watch and try to push the button with every strike. It sounds impossible but it can work with a little practice. We don’t get much lightning here so I have yet to invest in a lightning trigger but it’s a device that senses the lightning and takes the photo for you. Pretty handy if you do a ton of lightning shots.

Lightning at Mount Hood and Lost Lake

(click here to view a large version in Brian’s gallery)

I have a couple of apps that show you live lightning hits so you can see if it’s worth heading out. And be ready if the conditions change. One of my favorite lightning shots at Lost Lake (above) was purely luck. I was there to take a photo of the sunset when a small storm popped up. I kept taking pictures until I got my shot.

WyEast: You’re based in Hood River, Brian. I’m wondering where you see the fine art scene going in the Gorge over the long term? Do you see art becoming a significant part of the Gorge and Mount Hood economy in the future?

Brian: It is definitely growing. I don’t think there were any art galleries in town when I moved here in 1997. Now it seems like there is one on every block. Many restaurants and breweries also display local artists. Hood River has over 20 new outdoor works of art on display around town. There are so many talented artists in the gorge. I think people are drawn to the quality of life and inspired by amazing beauty at our doorstep.

Stormy Gorge evening

(click here to view a large version in Brian’s gallery)

Art can play a significant part in the economy. It is just one more great reason for people to visit the gorge and it fits well with the winery and brewery tours, the Fruit Loop orchard tour and outdoor recreational tourism that the gorge is so rightly known for. I think the artwork can be a long-term reminder of the specialness of the area and for both tourists and people who live here. I love when people look at one of my pictures and it reminds them of some special times they have had here.

Spirit Falls on the Little White Salmon River

(click here to view a large version in Brian’s gallery)

One thing that I am very excited about is helping to organize a temporary art gallery event in downtown Hood River on July 1st -3rd week. Eighteen local artists, including myself, have banded together to showcase and hopefully sell our work. We are having beer and wine and small plates of food, with an opportunity to view work from wide variety of different types of artists.

We will all be on hand all three days to discuss our artwork. The event will be at 301 Oak Street in downtown Hood River. I encourage anyone interested to stop in and say “hello”!

WyEast: That sounds like a great event, Brian! As an artist working in the Gorge, what are some of the challenges you’ve faced in becoming established?

Brian: It has been a slow steady process. Sometimes it seems agonizingly slow. When I first started taking pictures I didn’t dream that people would want to purchase them. I looked around and saw so many great photographers.

Abandoned homestead near Dufur, Oregon

(click here to view a large version in Brian’s gallery)

Early in my progression as a photographer I was lucky enough to be accepted into the Columbia Center for the Arts. At that time it was a critical place of support for me. They encouraged me and treated me as a true artist so that I began to think of myself that way. I started to sell some work and began to grow in confidence. Every year they would have a photo contest and I was fortunate enough to win first place among hundreds of entries, including some really talented photographers.

That was a big step for me. Then I branched out and started displaying my work in local bakeries, restaurants and brewpubs. I started to gain more followers and confidence. In the last year or so, I have started to post more consistently on Facebook (www.facebook.com/BrianChambersPhotography/) and connect with people there.

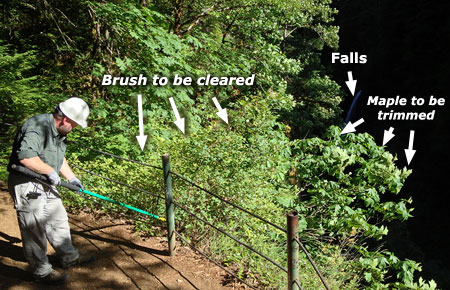

Brian teaching photography on a recent Friends of the Gorge outing

I have also begun teaching a little (including the Friends of the Gorge hike where we met). It is something I really enjoy and want to get better at, and something I have considered doing more frequently in the future.

Hood River is full of talented photographers and artists and most of them have been really supportive and welcoming to me.

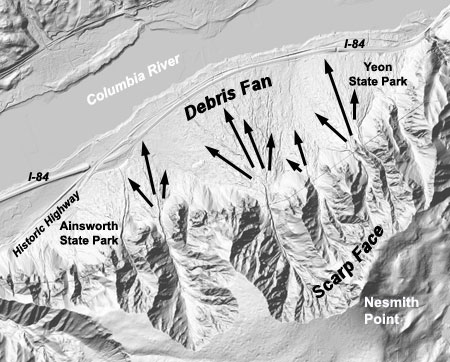

WyEast: When we met recently on that Friends of the Gorge hike, we talked about the controversy over oil and coal trains traveling through the Gorge. Since then, of course, a worst-case scenario unfolded when an oil train derailed in Mosier on June 3 of this year. What are your thoughts on the oil and coal trains moving through the Columbia River rail corridor?

Brian: That was a real eye opener for me. I had been out for a road bike ride in the exact location ½ hour before the accident. When I heard about it I actually went to take pictures from across the river. You can see a time lapse I took on my Facebook page. Just watching all the black smoke block out the view of Mt Hood was really a horrible sight.

Brian captured this video of the June 3rd oil train crash in Mosier, Oregon

(click here to view a large version of this video in Brian’s gallery)

I got stuck in a traffic jam heading home. It took me 2 hours to get home when it would normally take me 10 or 15 minutes. It really made me think about how the unique geography and infrastructure of the Gorge can really amplify any disaster. There are very limited driving options, and if one or two roads are closed people can become trapped.

I also think the accident was not a worst-case scenario. It was lucky it didn’t happen in the center of Mosier or Hood River, where there is a lot more potential for damage and it was lucky it happened on an unusually light wind day. If it had been windy I can only imagine how bad the fire could have been.

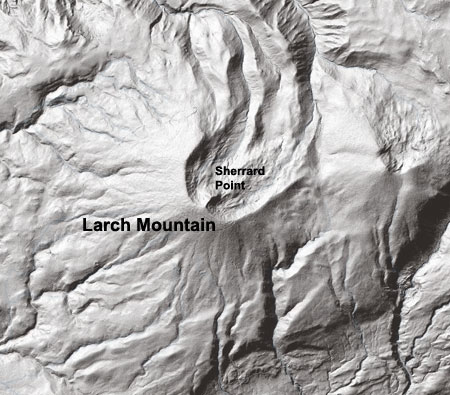

WyEast: You’ve hiked the trails of Mount Hood and the Gorge and have seen the growing crowds. Many are concerned that the area is being loved to death. What are your thoughts?

Brian: Wow, what a question. This is something I think about almost daily. Even in my short time here I have seen a tremendous change in the volume of hikers to areas that were once quiet and relatively unknown, like the Columbia Hills Park and Memaloose Hills. I used to go there in the spring and see almost no one. This year they were just packed with people. Which, on one hand, is wonderful that people are out there learning to love the gorge and discovering new places. It is great for society that people are out exercising and recharging in nature. I feel like people will fight to save places once they see how special they are.

Columbia Hills State Park in spring

(click here to view a large version in Brian’s gallery)

On the other hand, overcrowded trails and unsafe parking lots are a real concern and take away from everyone’s enjoyment. As a photographer, I am always looking for the un-crowded wild places and I am afraid as I share them I might be contributing to them becoming crowded and over used.

There is an area near The Dalles that I am just in love with right now and I went there more than a dozen times the last couple years during the wildflower bloom and saw less than a handful of other hikers, and usually didn’t see anyone. Although part of the reason for that is starting my hike before 5 AM! I am torn between never telling anyone about it and wanting everyone to know how amazing it is. The word is already getting out and I suspect it will be packed in a couple years.

Mount Hood from an “undisclosed location”…

(click here to view a large version in Brian’s gallery)

I guess I am an optimist. Nature seems to have the ability to not just heal people, but also itself. Just last week I was walking through the Dollar lake fire on Mt Hood. A few years ago it was a scene of total destruction. Everything dead and blackened. Now it’s hard to see the ground due to the huge number of flowers. If we can just try to get out of the way the land can usually do amazing things to recover from damage.

Gorge Sunset near Mitchell Point

(click here to view a large version in Brian’s gallery)

Ultimately, I think the best answer is more trails. That is why I fully support the work you and others like you are doing. Saving the remaining wild places and creating sustainable hiking trails. I hope as the crowds worsen that will become a bigger priority for more and more people.

WyEast: Last question, and one you probably knew was coming: you’re a veterinarian by trade, so I’m wondering if you’d like to weigh in on bringing dogs into the Gorge? And in particular, what are some tips you would offer for keeping dogs (and people) safe, based on your experiences as a care giver?

Brian: Well, one disease that people new to the area may not have heard of is salmon poisoning. Don’t let your dog eat raw salmon or steelhead. It can cause severe vomiting and diarrhea that can be fatal. As I am sure all hikers already know, there are a few ticks in the area! There are plenty of good tick control medications available for your dog.

East Gorge rainbow

(click here to view a large version in Brian’s gallery)

There are lots of dangers out on the trails and roads most of which can be avoided by keeping your dog on a leash and using common sense. I just recently saw a dog that was bitten by a rattlesnake on Dog Mountain. I have seen dogs killed by heat stroke, dogs killed by trains, falls from cliffs, cuts caused by skis, dogs lost in the wilderness, attacked by coyotes and other wild animals, falls from the back of pickup trucks, and too many hit by cars to count.

We also have a lot of poison oak in the Gorge. Keeping your dog on a leash is also a good way to make sure he stays out of poison oak, which can also be transferred to you from your dog’s coat.

Spring sunset in the Gorge from Memaloose Hills

(click here to view a large version in Brian’s gallery)

Lastly, just like you and I, you should avoid overdoing the activity level for your dog’s fitness level. If you have an out of shape dog that doesn’t exercise, don’t start with a long bike ride on a hot day. As your dog starts to age you need to start to reduce the length of the hikes and bikes to ones that will not cause them pain or distress.

It can be hard to do because the dogs often want to go, even when their body is unable. Talk with your vet if your dog is slowing down or seeming stiff and sore, as there are plenty of options to help with that.

WyEast: That’s great information! Thanks for taking the time to chat, Brian – and for celebrating the Gorge and Mount Hood with your amazing photography. We look forward to seeing more of your work!

Brian: It really was my pleasure.

_______________

You can support Brian Chambers’ photography by following him on Facebook:

Brian Chambers Photography on Facebook

Through July 15th, Brian will be donating 20% of proceeds from photos he sells to people who mention this article to the Friends of the Gorge, Trailkeepers of Oregon (TKO) and the Columbia Land Trust, so it’s a great time to support him! (please note that this excludes the July 1-3 pop up gallery)

Check out more of Brian’s images at:

Brian Chambers Gallery on Zenfolio

And you can contact Brian directly through e-mail by clicking here.

And finally, learn more about the July 1-3 pop up art gallery in Hood River at: