One of the dozens of unnamed, unmapped and off-trail waterfalls hidden in the canyons of the Opal Creek wilderness. This rarely visited falls is on Henline Creek

Heading south from Portland along old Highway 99E brings you first to the historic river town of Milwaukie, then up a forested bluff, past the end of the MAX light line and to the Oak Grove district of Clackamas County. From here, the old highway turns southeast, and makes a long, straight (and dreary) descent through the clutter of strip malls and used car lots on its approach to the edge cities of Gladstone and Oregon City. Normally, this is a grim part of this drive, but that last descent holds a surprise on clear winter days: a prominent cluster of mountain ridges on the horizon just high enough to be snowcapped well into June. What are these peaks?

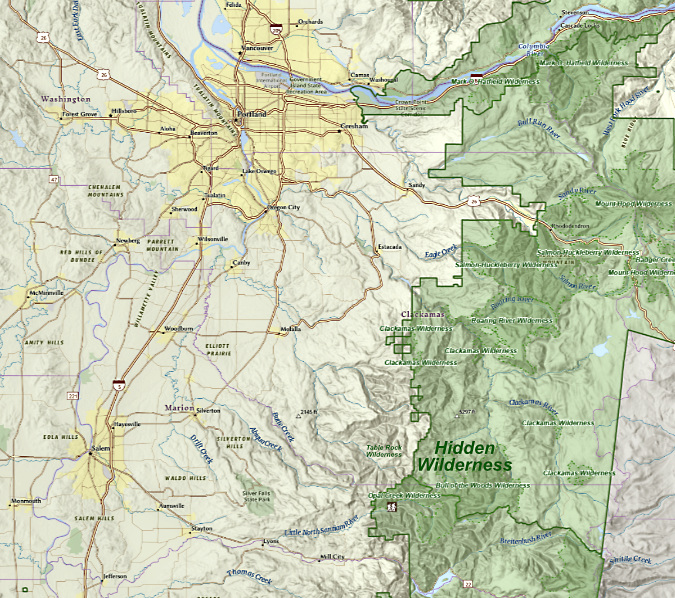

These are the high crags and ridges that form the rugged crest of the Bull of the Woods Wilderness, the adjoining Opal Creek Wilderness and nearby Table Rock Wilderness areas. The Bull of the Woods and Table Rock areas were protected by Congress in the landmark Oregon Wilderness Act of 1984 and protection for the Opal Creek area followed in 1996. Before it was protected in 1984, the Bull of the Woods area was known to conservationists as the Hidden Wilderness. It’s an apt name and one that I’ll use interchangeably in this article, because despite the surprisingly close proximity to nearly 3 million people in the Willamette Valley, this wilderness remains mostly unknown today.

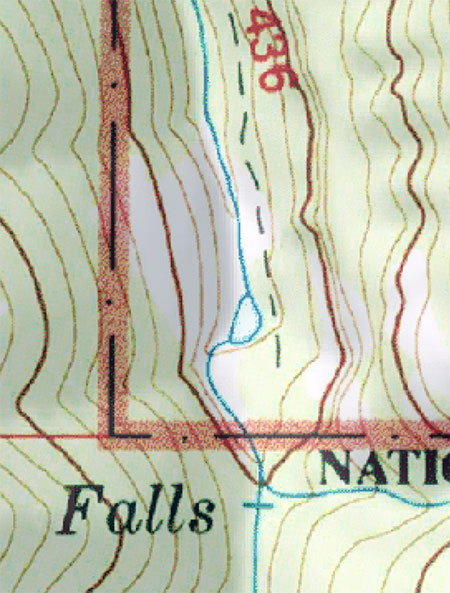

The Bull of the Woods, Table Rock and Opal Creek wilderness areas are located 30 miles due west of Salem and about 50 miles southeast of the Portland Metro Area.

[click here for a larger view]

We often say this about the lesser-known gems in our scenery-overloaded corner of the country, but if these areas were located in any state east of the Rockies, they’d be a major attraction. More than a dozen craggy peaks across the three wilderness areas rise above 5,000 feet, and the network of streams that radiate from this complex of mountains and steep ridges are among the most pristine in Oregon.

Together, the streams combine to form the beautiful Collawash River, Hot Springs Fork of the Clackamas, Molalla River and Little North Fork of the Santiam. These rivers are known for their unusual clarity, thanks to their protected headwaters.

Sawmill Falls is located on the Little North Fork of the Santiam River that flows from the Opal Creek Wilderness. This photo was taken just before the Bull Complex Fire impacted this part of the Little North Fork in 2021

Opal Creek, a major tributary to the Little North Fork and the namesake for its own wilderness. This photo was also taken before the Bull Complex fire in 2021

The Hidden Wilderness high country is also dotted with dozens of subalpine lakes and tarns that fill cirques and valleys left behind 15,000 years ago by ice age glaciers, when the peaks of the Hidden Wilderness rose high above the timberline. Below the lakes and peaks, dozens of spectacular waterfalls are hidden in the deep, forested canyons. These remain mostly unnamed and little known, and are inaccessible by trail.

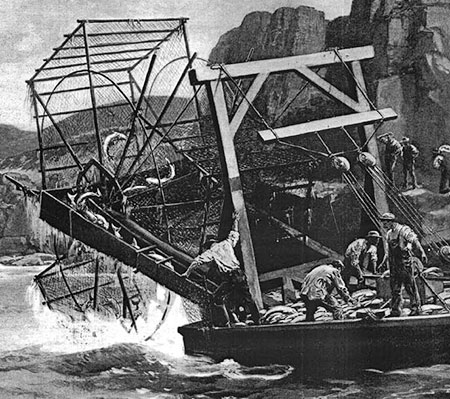

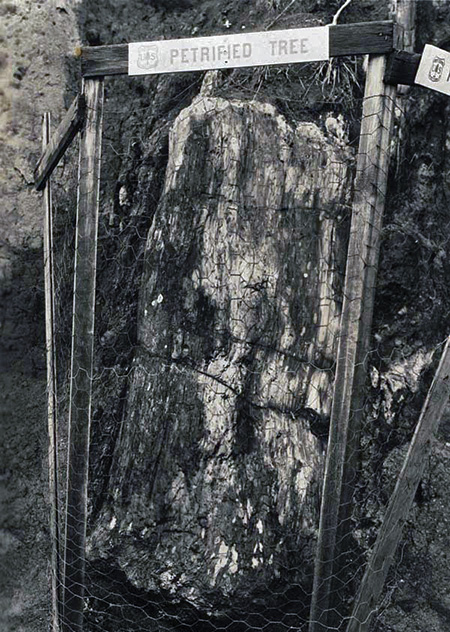

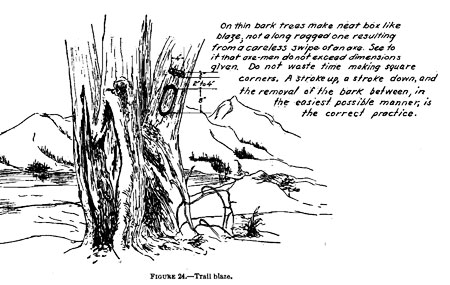

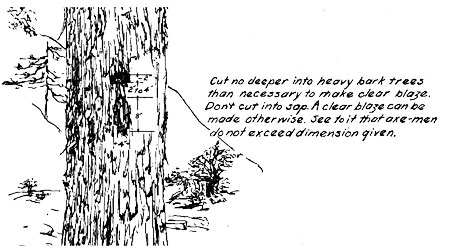

A surprisingly dense network or trails traverses the area, however, though they weren’t built with hikers in mind. Some of these trails were built in the late 1800s, during a mining boom that saw a major influx of human activity when gold was discovered along the Little North Fork in 1859 – the same year the State of Oregon was admitted to the union.

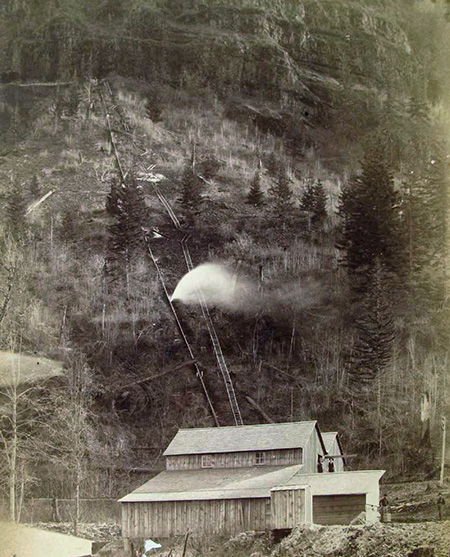

Small-scale hard rock mining later expanded across the mineral-rich Hidden Wilderness region to include copper, zinc and lead. Silver King Mountain, in the heart of the wilderness, was named for one of these mining claims. Today, old mining shafts and rusted relics from this era still remain scattered through the forests of the Hidden Wilderness, adding to the mystery and intrigue of the area.

Henline Falls in the Opal Creek Wilderness is named for a miner who made a claim here in the late 1800s. Abandoned mine shafts can still be found along the creek, including one at the base of the falls. This photo was taken before area was impacted by the 2021 Bull Complex Fire

Hikers exploring the abandoned mine at Henline Falls. Mining relics from the late 1800s and early 1900s are found across the Hidden Wilderness

Many of the area trails were built later, when the area was first designated as national forest in the early 1900s. These trails were built to connect the network of fire lookout towers built atop several peaks in the Hidden Wilderness and to the subalpine lakes that provided a water source for lookouts and stock animals. In those early days of the Forest Service, trails also connected guard station, where forest rangers were stationed and “ranged” the forest trails to protect public lands from illegal logging and grazing. Hikers would not discover these trails until the 1920s and 30s, when the first roads brought weekend campers to the forest.

The original cupola-style Battle Ax Mountain fire lookout in the 1930s (USFS)

The Bull of the Woods fire lookout in the 1950s with Mount Jefferson in the distance (USFS)

Most of the historic lookouts and guard stations in WyEast Country were destroyed by the Forest Service in the 1960s, deemed obsolete when air surveillance for fires took over and the modern cobweb of logging roads transformed access within the forest. The old lookout on Bull of the Woods Mountain survived until very recently, when it was destroyed in the Bull Complex Fire in 2021. More than a dozen lookouts and guard stations once stood in the Hidden Wilderness, but only the unique stone Pechuck Lookout structure on Table Mountain and the historic Bagby Guard Station survive today.

Bagby Hot Springs Guard Station in 1913, among the few guard stations where rangers were guaranteed a warm bath every night!

Most of the early 1900s lookouts and guard stations were destroyed in the 1960s, but the historic Bagby Hot Springs Guard Station survives today and serves as a northern gateway to the Bull of the Woods Wilderness

For many years, an unofficial network of dedicated trail advocates has worked to keep the historic network of trails in the larger Clackamas area alive in the face of years of Forest Service neglect, and, more recently, the wave of wildfires that have brought many of the trails here to the brink of being lost forever. A reputation for lawlessness and confusing, poorly maintained trailhead access roads left over from the big logging era of the 1960s, 70s and 80s in the Clackamas River corridor have also discouraged hikers who might otherwise come here to explore this wilderness gem, hidden in plain sight.

The trail system in the Hidden Wilderness has been in slow decline for decades, first from logging that destroyed many trails and trailheads, and later through lack of maintenance and the impacts of frequent wildfires

The unprecedented attack on federal agencies in recent months by the current administration will only add to the struggle to keep the existing trails open in the near term. But in the longer term, there’s no reason to believe this regrettable trend won’t be reversed. This administration will be replaced in just a few short years, and the demand for more and better trail access to our public lands will only grow in that time.

A strong public backlash against the administration’s public lands policies has organized in recent weeks, underscoring the obvious — that people deeply value our public lands, and expect to have access to them. It’s also true that we are in the middle of a generational transition in national leadership, with younger leaders much more likely to view conservation, clean water and recreation as the primary purposes of our public lands.

With this longer, more hopeful future in mind, the rest of this article focuses on the Hidden Wilderness as it could be, and can be. It’s a positive vision for restoring and expanding trail access into the area, embracing and restoring some of the history that has been lost, and in doing so, provide the Hidden Wilderness the care this remarkable place deserves.

Return of Wildfire: It’s still (mostly) a good thing…

The Janus Fire grew rapidly and combined with other blazes to become the Bull Complex in the summer of 2021 (USFS)

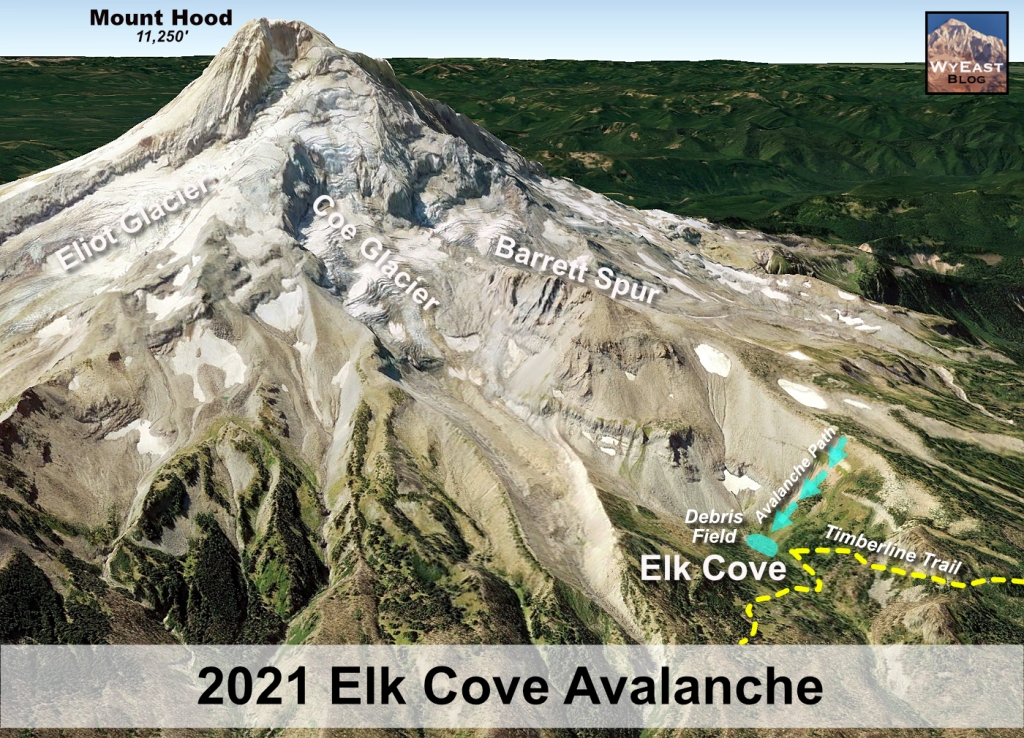

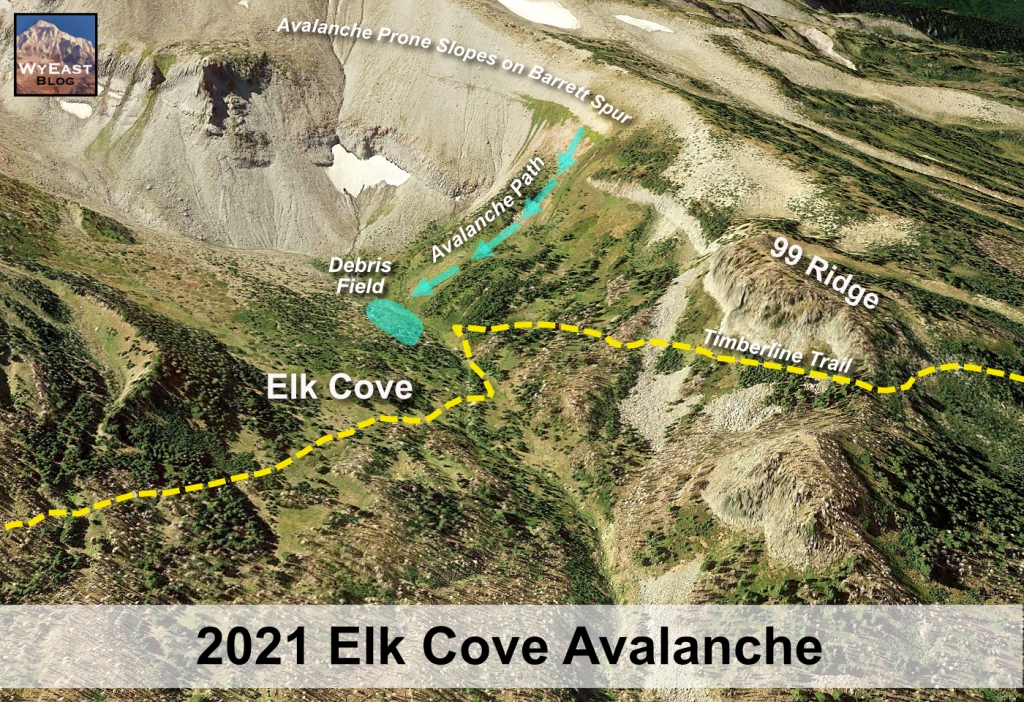

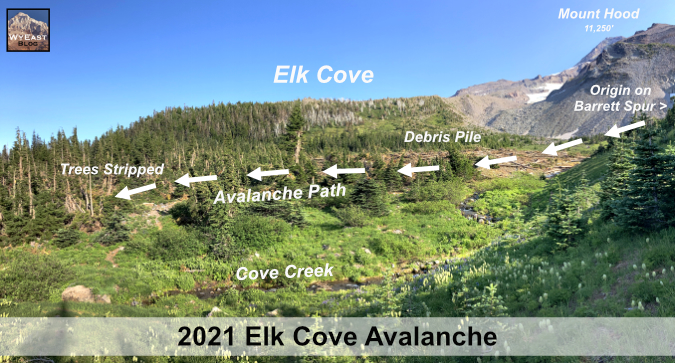

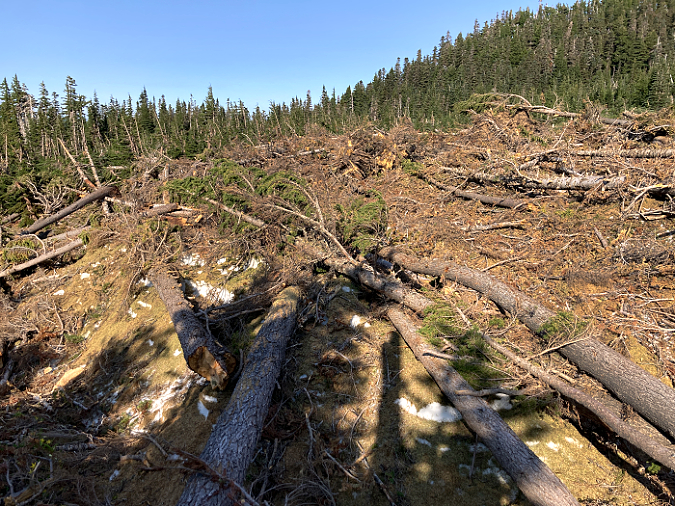

When the Janus Butte fire sparked on a ridge above the Collawash River in August 2021, it felt like a recurring bad dream for many, given the series of devastating fires that had roared through the Mount Hood National Forest in the fall of 2020.

While most of the very recent fires in WyEast Country (including the 36 Pit Fire in 2014, the Eagle Creek Fire in 2017 and the massive Riverside Fires in 2020) were notoriously human-caused, the Janus fire was different. Instead, this was a natural wildfire that began with lightning strikes that ignited several small fires in the Collawash River headwaters. By mid-August of 2021, these fires would merge with the Janus Fire and become known as the Bull Complex, named for the Bull of the Woods Wilderness, where they were advancing quickly.

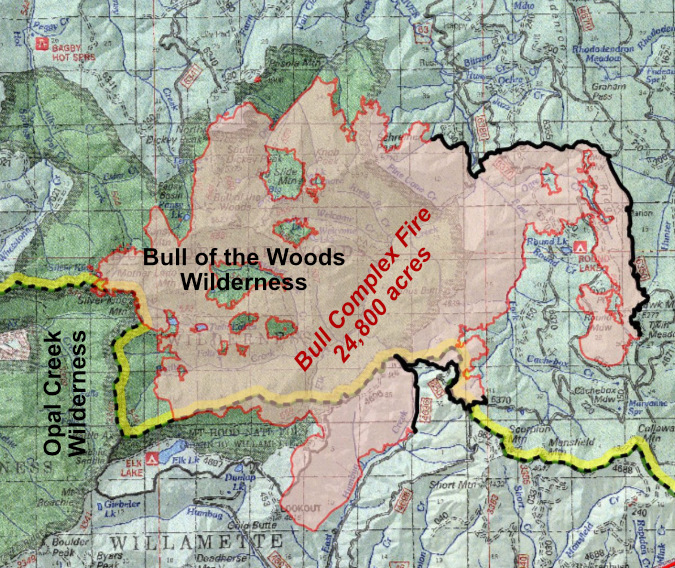

The Bull Complex eventually burned nearly 25,000 acres (shown in pink), with roughly half the Bull of the Woods Wilderness (in dark green) affected. This fire spared previously burned areas to the west, in the adjacent Opal Creek Wilderness, where the 2020 Beachie Creek Fire resulted in more than 90 percent mortality over much of the 190,000 acre extent

By the end of September 2021, the Bull Complex had burned just short of 25,000 acres. Though significant, this burn was only fraction of the 190,000-acre Beachie Creek Fire that swept through the adjacent Opal Creek Wilderness and 138,000-acre Riverside Fire that burned through the Clackamas River area to the north the previous year.

Together, this combination of natural and human-caused fires left a massive burn scar across much of the Clackamas River and Little North Fork watersheds that will take decades to recover. While science tells us that wildfires are a healthy and necessary part of our forest ecosystem, how could burns this extensive be a good thing?

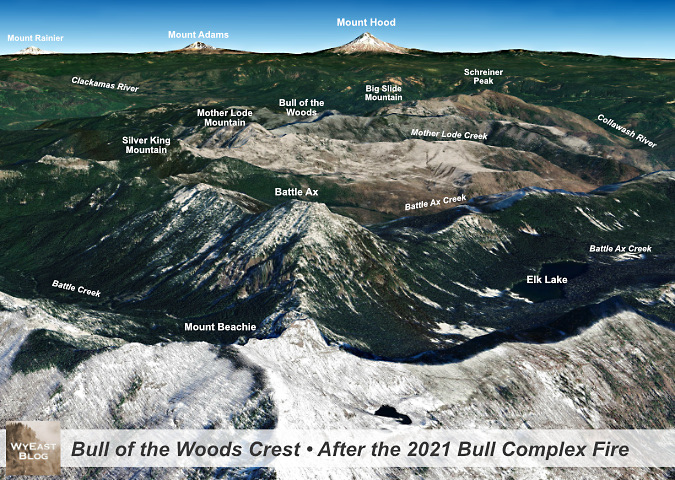

This aerial view shows the impact of the Bull Complex Fire on the heart of the Bull of the Woods Wilderness. The burned slopes of Mount Beachie (in the foreground) are from the much larger Beachie Creek Fire in 2020.

[click here for a large version]

The answer is nuanced. The combined effect of a century of fire suppression and our changing climate has resulted in an unsustainable sequence of fires in recent years in terms of their size, intensity and frequency. This will make forest recovery in some of the largest (and, notably, human-caused) burns much slower. But where recent burns were smaller and less intense, the recovery cycle is already well underway, and the benefits that science promises are already apparent in these places, including in the Bull of the Woods Wilderness.

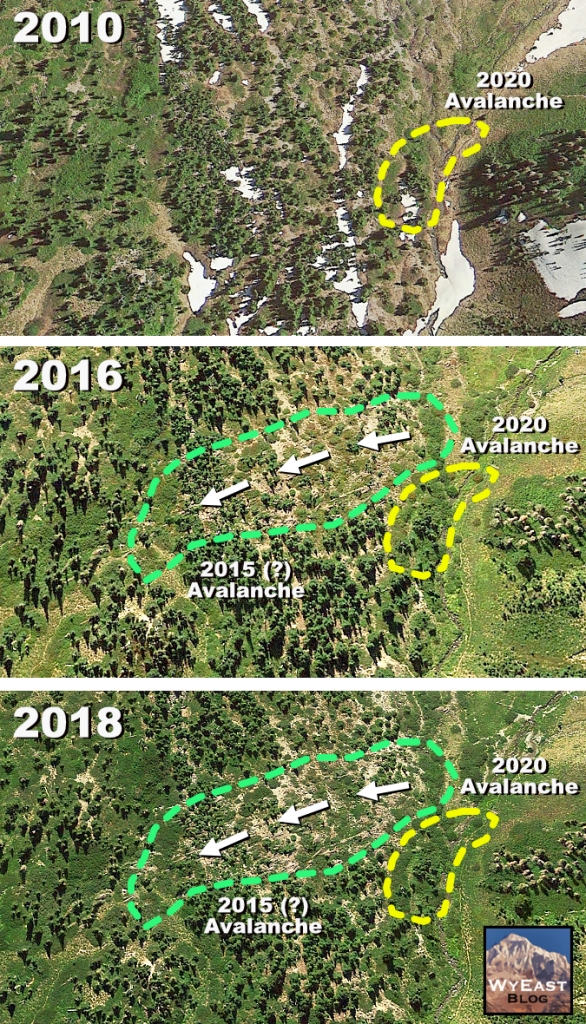

The Bull Complex Fire is a good example. The fire burned mostly along steep mountain slopes and ridgetops, including through hundreds of acres of standing snags from a series of earlier fires in the Bull of the Woods that swept through the heart of the wilderness in 2008, 2010 and 2011, completely clearing these slopes for what will most likely become beargrass and huckleberry fields for many years to come. The fire also skipped over several forested canyons that had been spared by earlier fires, allowing trees in these areas to continue to age as mature forests, retaining the biological complexity that only old growth forests can bring to a forest ecosystem.

While the Bull Complex was mostly a beneificial fire for the forest ecosystem, it wasn’t so kind to human infrastructure. It will take years to repair trails impacted by the fire, and many favorite camping spots at the high lakes were completely burned. Perhaps most distressing on the human side of the equation was the loss of the historic Bull of the Woods Lookout tower that as completely destroyed by the fire (more on that later in this article).

For the first few weeks, it seemed the 2021 Bull Complex Fire might spare the historic Bull of the Woods fire lookout, but in early September of that year, the fire surged west, completely destroying the old structure (TKO)

Just three years after the Bull Complex Fire, the 2024 fire season threatened to bring yet another blaze to the Bull of the Woods when Sandstone Fire flared up just north of the Hot Springs Fork last September. Like the Bull Complex, this fire threatened the historic structures at Bagby Hot Springs that had been spared by the 2021 fires. Fortunately, the fire was soon contained and cool fall weather set in before it could spread south to the Bagby area.

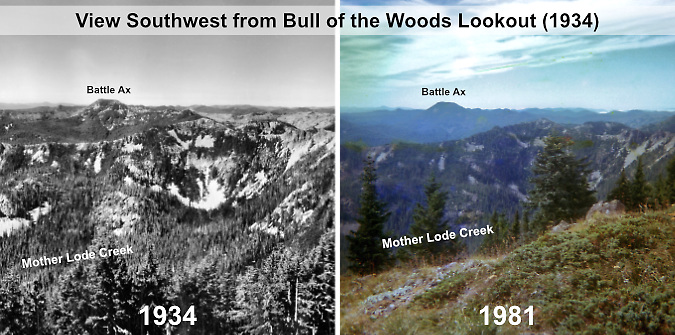

The rapid succession of wildfire in recent years in the Hidden Wilderness area has felt jarring mostly because fires here had been successfully suppressed for so long. There was a sense that our forests could remain green and unburned, indefinitely, and that they had always looked this way. But if you look closely at photos taken in the 1930s as part of an expansive Forest Service surveying effort, the forests then looked much like our fire-impacted forests of today. While the current pace of fires feels alarming, we are looking at a forest ecosystem that is much closer to its pre-forest management days, with an ecosystem in a far healthier state that was more adapted to fire.

The following photos are from that 1930s survey, and clearly show a forest that had repeatedly burned with smaller, beneficial fires in the decades prior. For the first image, I paired the 1930s view with one took in 1981, showing how the forests south of the Bull of the Woods had already covered the landscape in the absence of fire during the 50-year period between the images:

[click here for a large version]

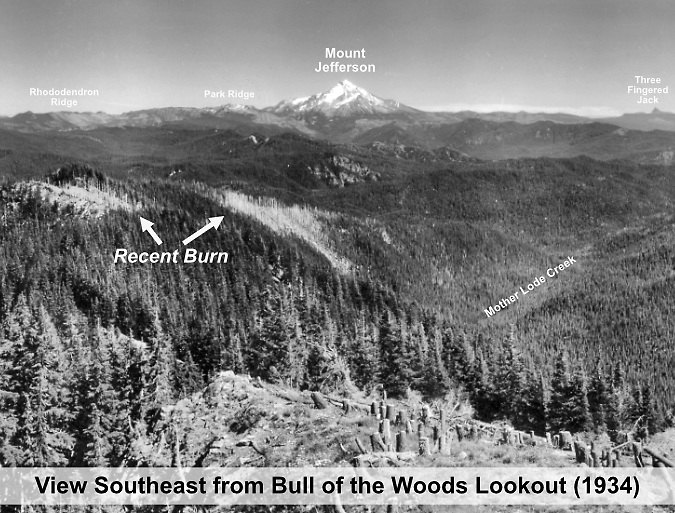

This 1930s view from Bull of the Woods shows recent burns along the ridges to the southeast that were likely ignited by lightning, and only burned small patches – a desirable “mosaic” pattern that is beneficial to forests:

[click here for a large version]

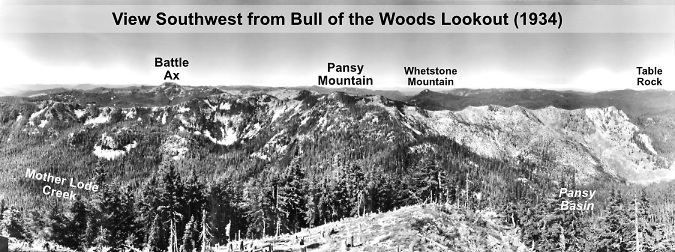

Looking to the west from Bull of the Woods in the 1930s revealed yet another recent burn in the Pansy Basin, and area that is now forested and has largely survived more recent fires:

[click here for a large version]

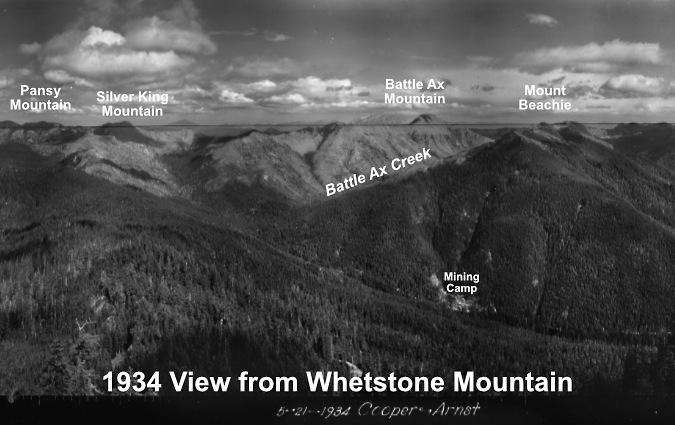

This view is from Whetstone Mountain, looking east toward today’s Bull of the Woods Wilderness, showing much of the upper headwaters of Battle Ax Creek burned. Some of these early fires may also have been human caused by mining activity in the area – a mining camp is visible in this image:

[click here for a large version]

With the recent series of fires repeatedly burning the area, what will the Hidden Wilderness look like in another 50 or 100 years? We have a local example that might provide a preview: Silver Star Mountain, which looms on Portland’s northeast horizon. This area experienced a series of devastating (and mostly human-caused) fires in the early 1900s. Due to erosion and extensive canopy loss from these fires, the forest didn’t fully recover, leaving large areas of subalpine meadows and beargrass fields that persist today. The spring wildflower season and sweeping views year-round from the open ridgetops make it a popular hiking destination and important island of open habitat in the surrounding sea of forest.

Spring bloom along Ed’s Trail on the north ridge of Silver Star Mountain.. This area is still recovering from devastating fires more than a century ago

Like the peaks and ridges that make up the Hidden Wilderness, Silver Star Mountain forms the western slope of the Cascades, taking the full brunt of Pacific storms. The intense weather has contributed greatly to the slow the recovery at Silver Star through erosion and brutal winters that stunt emerging forests. By comparison, today’s landscape at Silver Start Mountain looks a lot like the one that existed in the 1930s lookout surveys of the Hidden Wilderness, suggesting what the future might look like here.

The long-term impact of recent fires on human infrastructure in the Hidden Wilderness are easier to predict. We’ve learned in the recovery from the 2017 Eagle Creek Fire in the Columbia Gorge that fires have long-term impacts on trails as the forest recovers, from ongoing erosion to falling snags and explosive growth of the rejuvenated understory that continually overcomes trails.

Silver Star Mountain gives a good idea of what most of our forests looked like before fire suppression began in the early 1900s. The open peaks here provide important subalpine habitat that we will now likely see in the Hidden Wilderness as it recovers from fire

Access roads have also been affected by the fires, especially in the heavily burned Opal, Battle Ax and Mother Lode creek valleys, adding to questions about their sustainability in an era when industrial logging no longer provides revenue to justify the extensive logging road network built in the 1950s, 60s and 70s, and radical cuts to Forest Service budgets by the current administration raise serious questions about our ability to maintain today’s network of forest roads in the future.

Drawing a new vision from the past?

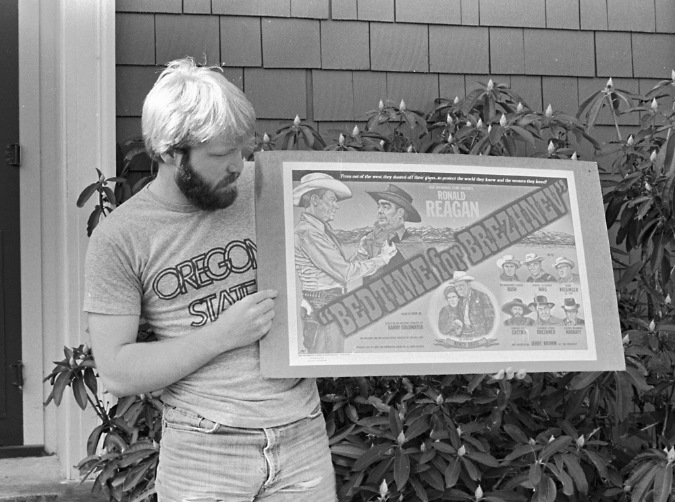

Way back in 1980, when I was college freshman at Oregon State University, I jumped into the Oregon conservation movement with both feet. Commercial logging on our public lands was moving at an appalling pace, and the few wild places left in the Western Cascades were very much in peril. As Mark Twain wrote, “history doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes”, and that first year of Ronald Reagan’s presidency felt a lot like what we are experiencing now from a conservation perspective — albeit with more grace and nuance, to say the least, Yet, the intent was the same: slash public agency budgets and sell off from our public lands where they could be sold.

The author with a poster fundraiser for the OSU Student Chapter of the Sierra Club back in the day. At $10 this raised some funds and made it onto a lot of dorm room walls!

In response, local activists across Oregon were organizing to advocate for very place-specific islands of intact wilderness that had been spared from logging. The strategy of the day was to publish hiking guides and brochures to help advertise what was at stake with these remaining, still untouched gems. My own involvement was with the Salmon-Huckleberry Wilderness effort, where I put together a brochure and map in collaboration with a conservation group based in Portland to help get the word out. Thankfully, the Salmon-Huckleberry was among the areas protected in the landmark, Republican-sponsored 1984 Oregon Wilderness Act that Ronald Reagan eventually signed into law.

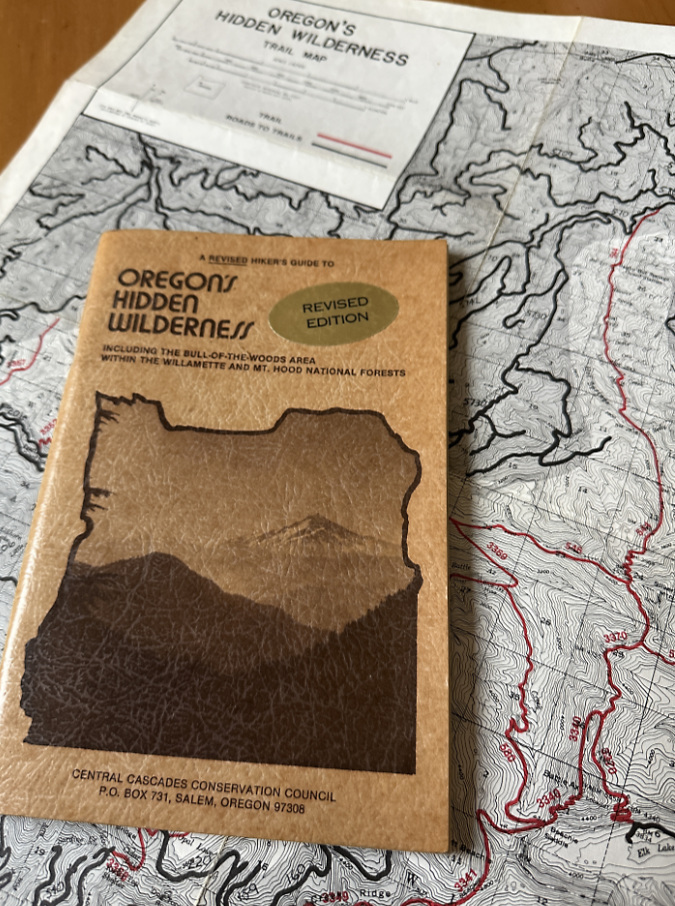

Of these local, grass-roots efforts around Oregon in the late 70s and early 80s, nobody topped the fine field guide published by the Central Cascades Conservation Council, a Salem-area group that gave the Hidden Wilderness its name. Their excellent guide (pictured below) not only provided the most complete trail descriptions for the area to date, but also included an excellent, folded topographic trail map tucked into the back! I was hooked, and made my first overnight trips into the Hidden Wilderness in the summer of 1981.

One of my treasured copies of the Oregon Hidden Wilderness guide and map – you can still find these as used book stores now and then!

The core strategy of those late 70s and early 80s conservation efforts was “eyes on the forest”, the idea that bringing people to endangered places was essential to creating public awareness and advocacy. Thus, the many brochures and guides created by non-profits in that era to introduce people to less-visited places that were gravely threatened by logging. They were largely successful in that objective, as some long-forgotten trails in placed like the Hidden Wilderness were newly “discovered”.

The Bull of the Woods and Table Rock areas were included in 1984 wilderness legislation and the Opal Creek Wilderness was created through a later bill in 1996. These were big wins for the conservation effort, bringing long fought-for protection to the greater Hidden Wilderness area.

The author atop Battle Ax in the fall of 1981

However, these conservation victories in the 1980s and 90s also marked the beginning of a long cycle of decline of the historic trail networks across our national forests as we entered the current era of federal defunding of our public lands. Continued logging on the borders of the new wilderness areas has also continued to chip away at the gateway trails and trailheads, and recent fires have compounded the deterioration of trails access to trailheads.

Therein, lies the opportunity. With trails once again on the brink of being lost forever, and a public both horrified by the administration’s attack on public lands and eager to have better access to the places, are we at a moment for a renewed vision for our public lands?

I think so! There’s a saying from the civil rights era that applies: “during the good times, plan for the bad, and during the bad times plan for the good” We’re certainly in a bad time, but I do believe a period of reconstruction is ahead. So, in that spirit, read on for one way in which the Hidden Wilderness could be reimagined when those better times arrive.

Making the Hidden Wilderness less “hidden”…?

The “eyes on the forest” strategy can still be a powerful, lasting solution to some lingering challenges facing the Hidden Wilderness today. Much of the illegal and destructive behavior that has long dogged backcountry in the Clackamas River corridor traces directly to a lack of eyes on the forest. Even a slight uptick in visitors traveling to campgrounds and trails is a proven antidote to lawless activity like dumping, illegal shooting off-roading outside designated areas.

The existing trail network in the Hidden Wilderness extensive and lightly visited, with plenty of room to accommodate more hikers if trails and trailheads were given more attention. Bringing new hikers is also a help to gateway communities with recreation-based economies who increasingly depend on tourist dollars to survive.

The author backpacking the Hidden Wilderness in 1981. Short shorts were just a thing back then, no further explanation provided…

Most importantly, a program to rebuild and expand the trail network in the hidden Wilderness would help fill the deep deficit in outdoor recreation opportunities that exists in the greater region. The number of trails within a couple hours of Portland has actually decreased since their peak in the 1930s while the metropolitan area population has ballooned from just 500,000 in 1940 to more than 2.5 million residents today – a five-fold increase whose impact is obvious on our trails. It’s not a surprise that maintained trails with good access are often very crowded today.

As communities in the Portland region and Willamette Valley continue to grow, it makes sense to reinvest and improve the trail networks that already exist in places like the Hidden Wilderness, right in our own backyard. It’s also an opportunity for everyday people to be part of that solution through volunteer trail work (more on that in a moment).

Twin Gateway Proposal

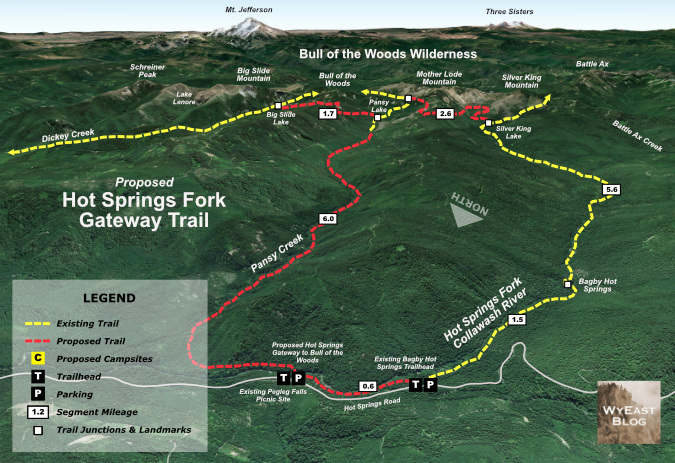

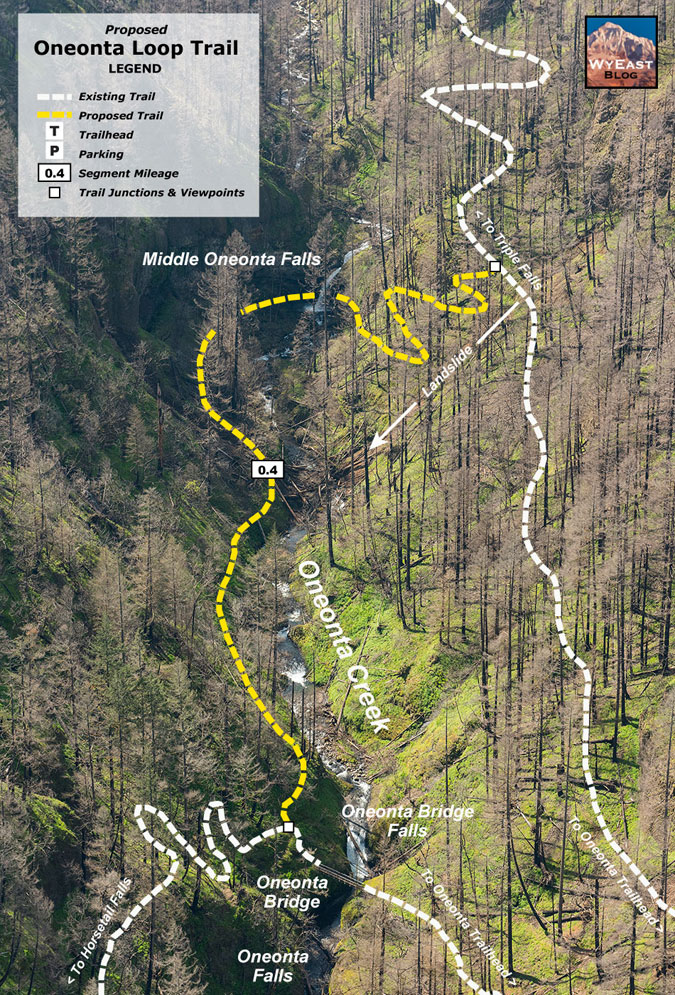

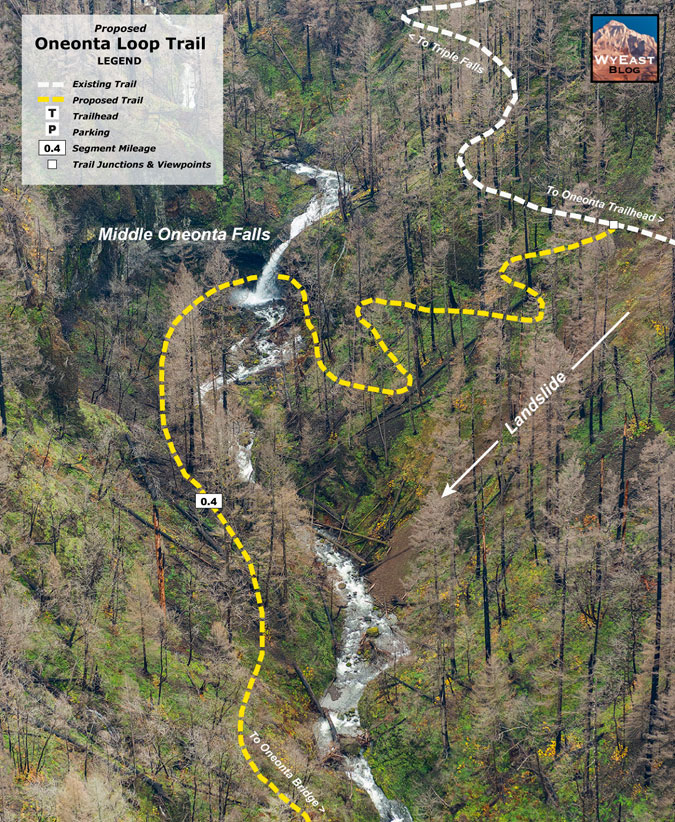

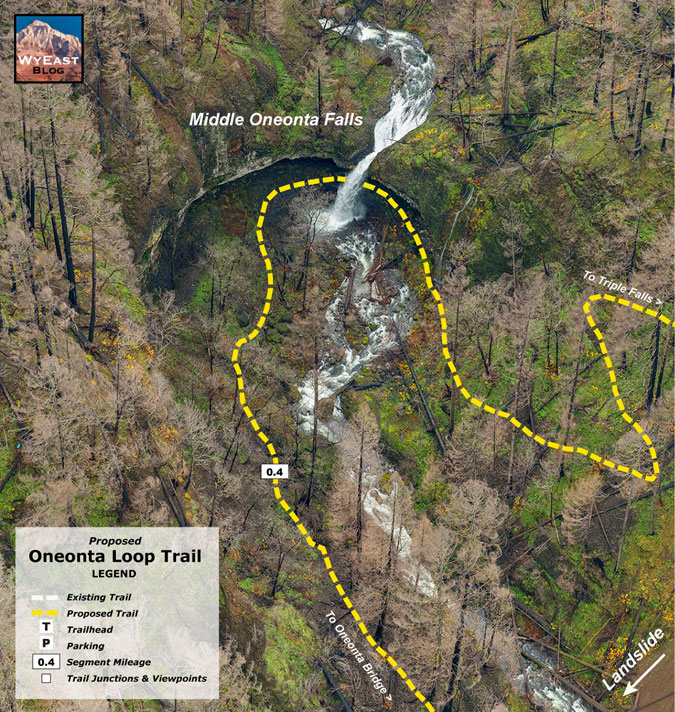

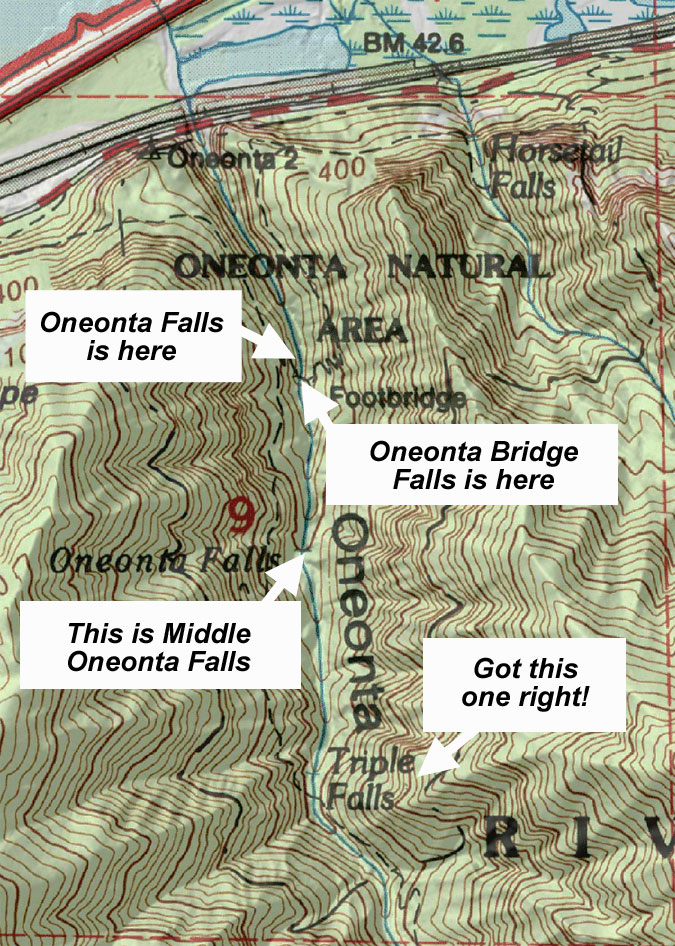

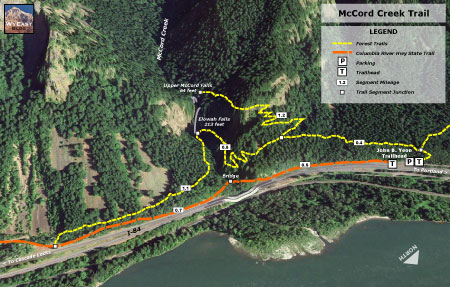

Though there are several existing access points of varying condition to the Hidden Wilderness, this article focuses on greatly improving the northern access from the Clackamas River corridor, along Highway 224, which functions as the most direct route from the Portland Metro region. Two new “gateway” trailheads are proposed (below).

The proposed Hot Springs and Collawash gateway trailheads in relation to the Portland Metro region and Clackamas River corridor

[click here for a large version]

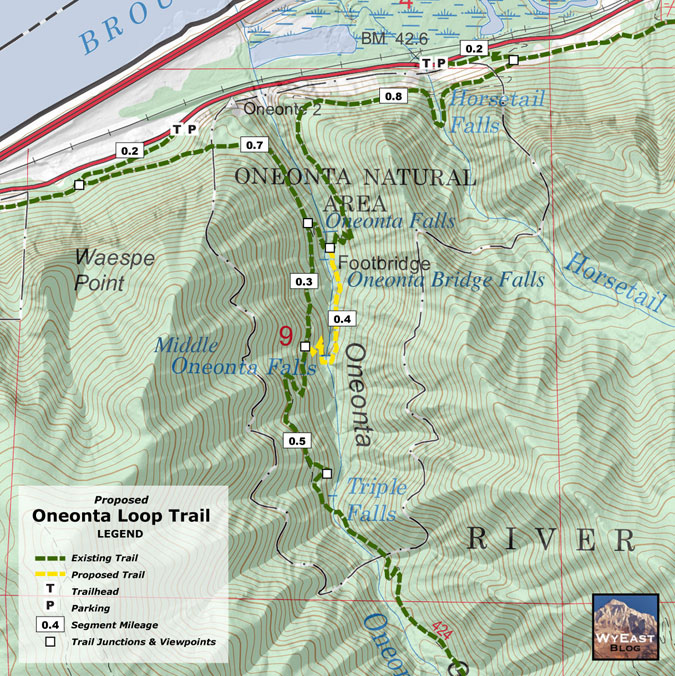

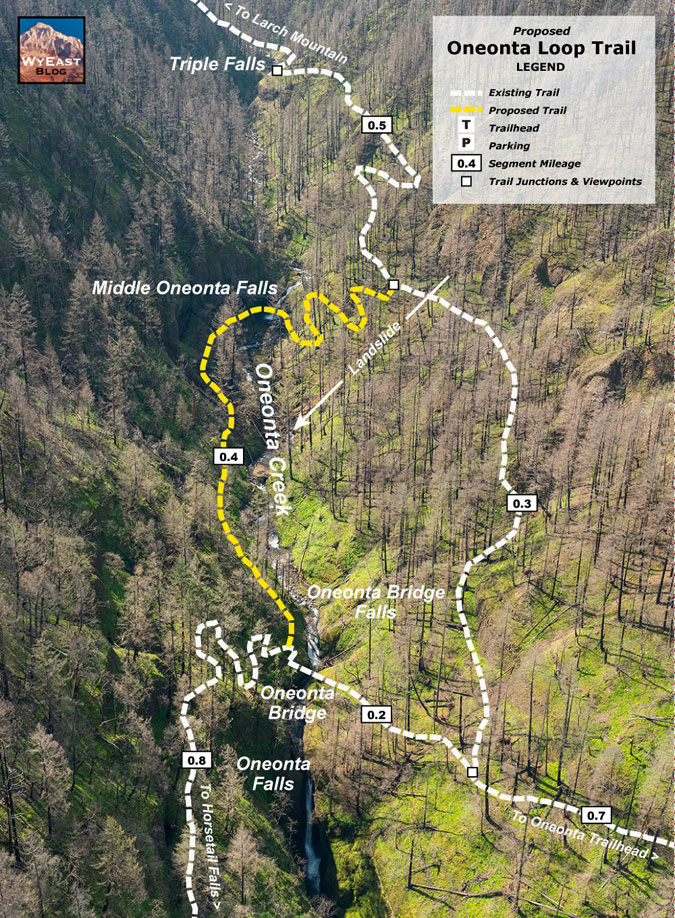

The first gateway trailhead would be along the Hot Springs Fork of the Clackamas, at the now-closed Pegleg Falls recreation site. This new gateway to the wilderness would feature a completely new trail along scenic, virtually unknown and (so far) unburned Pansy Creek, with a second, short connecting trail along the Hot Springs Fork linking to the already very popular Bagby Hot Springs recreation site.

The proposed Hot Springs gateway would repurpose the mothballed Pegleg Falls picnic site

The new Hot Springs trailhead would be the starting point for a dramatic loop trail system into the heart of the Hidden Wilderness, while avoiding further crowding at the Bagby parking area, where most visitors are there simply for a day to visit the hot springs. The new trailhead would also take advantage of the Pegleg Falls recreation site, a picnic area that has fallen into disrepair, but could easily be reopened and repurposed as a gateway trailhead.

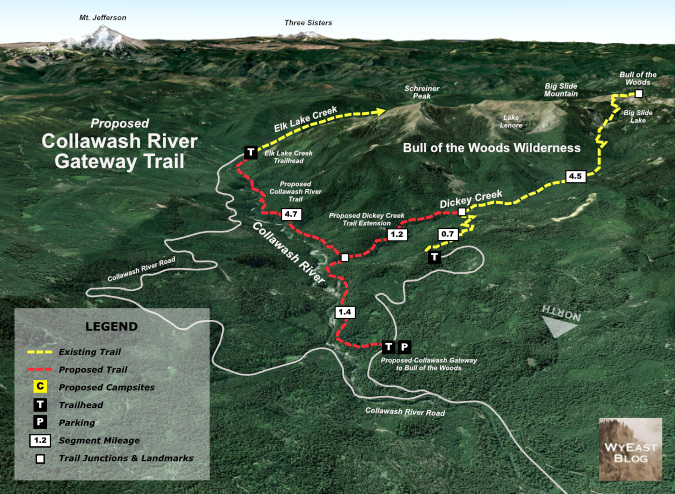

The second gateway trailhead would be along the Collawash River, just above its confluence with the Hot Springs Fork. This new trailhead would repurpose an overgrown logging yard just off the Collawash River Road. Like the Pegleg Falls site, it is easily accessed from paved roads, a significant improvement for those not wanting to navigate miles of deteriorating, poorly marked logging roads and the lawless activity that is too often found there.

For less experienced hikers, or people concerned about driving backcountry roads, this sign announcing miles of poorly maintained gravel roads ahead is an unwelcome sight. The new Collawash gateway trailhead would spare hikers five miles of backroad travel to reach Dickey Creek

The new Collawash gateway trailhead would also save backpackers ten miles of backroad travel to the sketchy Elk Lake trailhead with a new trail to the Elk Lake Trail via the Collawash River

With both proposed gateways, the main objective is to create loop trail systems into the Hidden Wilderness with easily accessible, well-developed trailheads that will not only draw new visitors, but also be easy to maintain, for law enforcement to patrol and for everyone to feel safer leaving a vehicle there overnight.

A second important objective is to provide more year-round recreation opportunities. Both new trailheads would be at the relatively low elevation of just 2,000 feet, and thus largely snow-free and mostly open year-round. The new trails along the Collawash River, Dickey Creek and Pansy Creek would be relatively low elevation routes, mostly under 2,500 feet, providing much-needed, all-season streamside trails to provide alternatives and take pressure off the limited number of existing, all-season trails in the region.

A closer look at both gateway trailhead concepts follows…

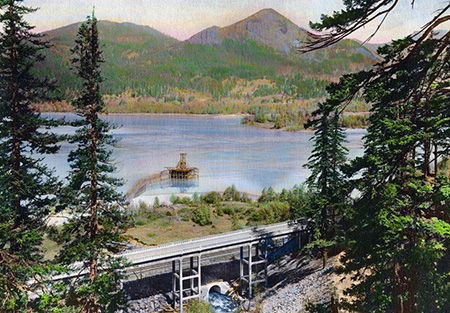

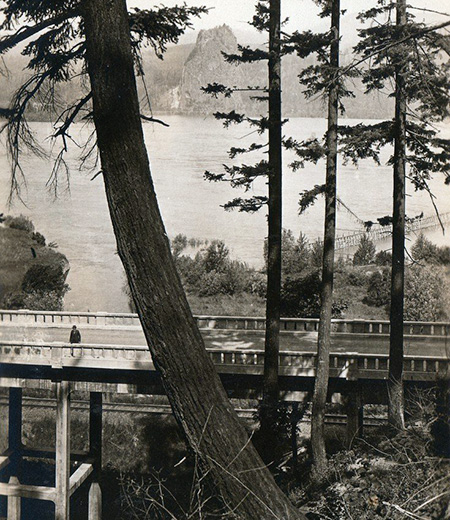

The Hot Springs Fork Gateway

The Hot Springs Fork gateway would salvage the long-abandoned day-use area at Pegleg Falls, a beautiful spot that really deserves to be restored. The site is just 65 miles from downtown Portland, and accessed entirely on paved roads. From the proposed gateway trailhead, a new footbridge across the Hot Springs fork would lead to a proposed Pansy Creek trial and a new Hot Springs connector trail to the Bagby trailhead, just upstream. The map below shows the concept in detail, and how these new connections would create a grand backbacking loop into the heart of the Hidden Wilderness.

[click here for a large version of this map]

The section of the Hot Springs Fork at Pegleg Falls is exceptionally scenic, with summer swimming holes for picknickers and upstream views of 20-foot Pegleg Falls. While the proposed trails would provide exciting new routes into the wilderness for backpackers, they would also serve casual hikers looking for a less challenging experience, as the first section of the new Pansy Creek Trail and proposed Hot Springs Connector would offer easy, streamside routes through lush forest.

Despite the closure of the picnic site, Pegleg Falls remains as a beautiful spot along the Hot Springs Fork that is now gated off to the public

Dilapidated chain-link fences and other leftovers from the defunct Pegleg Falls site could be responsibly removed or repurposed as part of creating a new gateway trailhead here

The new Pansy Creek trail would also bring a surprise for day hikers and backpackers, with an little-known series of waterfalls along the lower three miles of the proposed route. These have only been seen in recent years by a few intrepid waterfall explorers, though loggers likely explored the stream during they logging heyday of the 1960s, 70s and 80s. While the Pansy Creek valley is still recovering from heavy logging in the past, the valley has managed to escape fire in recent years, making this an especially lush rainforest route along the stream corridor.

For day hikers, the Pansy Creek waterfalls would be within a couple miles of the new gateway trailhead at Pegleg Falls. For backpackers, they would mark the start of an exceptional two-or-three day trek that takes them past waterfalls, mountain lakes and high peaks.

Beautiful Pansy Falls along the proposed Pansy Creek trail (Tim Burke)

Upper Pansy Falls along the proposed Pansy Creek trail (Tim Burke)

The upper extent of the loop also includes a proposed connecting trail between the Bagby and and new Pansy Creek trails, creating shorter loop options for both backpackers and day-hikers. This new connector and the proposed Pansy Creek Trail would join the existing wilderness trail system at Pansy Lake.

The proposed Pansy Creek trail would join the existing trail system at Pansy Lake, the stream’s headwaters

The new loop trails would also promote more use of the existing Bagby Trail, an important and historic route that is rarely visited beyond the popular hot springs site. As a result, this trail had fallen into disrepair over the years, and is only now being gradually restored by volunteers.

Do you recognize this waterfall? Not many would, even though it is located just beyond popular Bagby Hot Spring. Beyond the hot springs, this lovely trail is only lightly used, in part because of years of deferred maintenance

This excellent camping spot along the Bagby Trail is only lightly used today, but would be part of a spectacular new wilderness loop with the proposed new Hot Springs gateway trailhead

The Collawash Gateway

The new Collawash gateway trailhead would be the starting point for new trails along both the Collawash River and an extension of the Dickey Creek trail connecting to the new Collawash trail. Together, these new routes would create a spectacular loop reaching into the high country of the Hidden Wilderness (see concept map, below).

[click here for a large version of this map]

The Collawash River is already a popular spot in the Clackamas Corridor, and for good reason. The unique geology of the area and clarity of its tributary streams in the high country of the Hidden Wilderness make for a stunning canyon of deep, clear pools framed by enormous boulders and cliffs. An ancient landslide extends for several miles on the east side of the Collawash, continually reshaping the east wall of the canyon and creating steep whitewater rapids and deep pools along this way.

The new trail would follow the more stable west side of the canyon, in a section of river where the Collawash road climbs quite high and to the east of the canyon. The result would be a true wilderness experience, despite the parallel road corridor. This section of river has never had a trail, so only kayakers and rafters have been here to witness a canyon of spectacular beauty. The new trail would instantly become among the most scenic in the region, eventually connecting to the existing Elk Lake Creek Trail, which leads into the high country of the Hidden Wilderness.

Though paralleled by miles of logging roads, the upper Collawash River remains wild and spectacular. A new trail here would be among the most scenic in the region

The proposed new Collawash River trail and gateway trailhead would largely replace this current “gateway” to the Hidden Wilderness at Elk Lake Creek, where a massive clearcut on the mountain slope ahead greets hikers

Complementing a new Collawash River trail would be an extension of the existing Dickey Creek Trail downstream to the Collawash (see previous concept map). This would allow the Forest Service to abandoning the steep canyon wall descent that currently provides access to Dickey Creek, and even the old logging spur road used to reach the current trailhead. The purpose of this new trail is to provide direct access to Dickey Creek from a far more accessible trailhead, and offer a longer trail experience along this beautiful stream for day hikers or backpackers heading further into the Hidden Wilderness.

What would it take to bring these concepts to reality? More on that in a moment…

Bring back the Bull of the Woods Lookout?

For those who had visited the historic Bull of the Woods lookout over the years, the 2021 Bull Fire felt personal when it swept over the peak, burning the lookout and the traces of at least one outbuilding. Like most wilderness lookouts, it had been in disrepair, the result of limited federal agency budgets that made basic trail maintenance here a challenge and a general reluctance by the Forest Service to maintain fire lookouts that are no longer in use.

Lost in the 1991 fire – the plaque marking the Bull of the Woods fire lookout as a national historic site (Zach Urness)

The historic 1942 structure that burned was not the first lookout at Bull of the Woods. The earliest lookout here was built in the 1920s, and eventually replaced with the classic L-4 design structure that stood here for nearly 80 years. The frame for the original tower was pre-fabricated at the Zigzag Civilian Conservation Corps camp (now the site of the Zigzag Ranger Station). The frame, cabin and outbuildings were then assembled on site with the materials hauled in on pack animals.

The view from the catwalk on the Bull of the Woods lookout was 360 degrees, but it was the view to the southeast of Mount Jefferson rising over the backcountry of the Hidden Wilderness that was most captivating

The Bull of the Woods lookout was last staffed in the summer of 1964. Somehow, it was spared over the next few years when the Forest Service burned dozens of lookouts and guard stations around Mount Hood to the ground as aerial fire surveillance took over.

Thirty-two years later, it was added to the National Historic Register after being nominated by the non-profit Forest Fire Lookout Association. Like most listings for historic forest structures, the status did little to bring resources to preserve the building. Sadly, we have seen this play out across WyEast Country, with priceless, historic structures like the Little Sandy Guard Station and Timberline Trail shelters on Mount Hood falling apart in recent years before our eyes.

The fire took the lookout building at Bull of the Woods but restored the view of Big Slide Lake, far below

So, this seems to be the end of the story for the Bull of the Woods lookout… or is it? It doesn’t have to be, though it would literally require an act of Congress to replace it. There is precedent, in fact. In Washington State, the much-loved Green Mountain lookout had fallen into disrepair in the 1990s, and was finally closed to the public in 1994.

After efforts to make on-site repairs in the late 1990s failed to adequately restore the structure, volunteers worked with the Forest Service to completely remove the lookout, piece by piece, and restore it off-site over a five-year period. With the support of private foundation grants, the restored parts were then re-assembled on site in 2009.

Green Mountain lookout being reassembled on its perch in the Glacier Peak Wilderness in 2009 (Photo: Spokane Review)

This decade-long effort to preserve the lookout did not go unnoticed, however. The restoration of the Green Mountain lookout within the bounds of the Glacier Peak Wilderness triggered a lawsuit by the Montana-based Wilderness Watch conservation group. They challenged the replacement of the structure as a violation of the Wilderness Act, and in 2012 a federal judge agreed, ordering its removal. The newly restored lookout seemed doomed, once again.

This is where the act of Congress came in. Washington Senators Patty Murray and Maria Cantwell introduced legislation to specifically exempt the Green Mountain Lookout from the Wilderness Act, a bill that President Obama signed into law in 2014.

Volunteers hanging a stewardship program welcome banner at the Green Mountain Lookout in 2019, five years after the rebuilt structure was saved from demolition (Photo: Everett Herald)

Today, the lookout still stands as one of the most popular hiking destinations in the state of Washington. To ensure its care in perpetuity, the Washington Trails Association has partnered with the Forest Service to establish an ongoing stewardship program at the lookout to staff the structure with volunteers during the summer hiking seasons, serving as forest interpreters for hikers visiting the lookout and care for the structure, itself.

Could a similar case be made to restore the lookout at Bull of the Woods? It would be a heavy lift, to be sure, but it could also help further the cause of protecting – and sometimes even replacing – historic structures in our forests. After all, they were here long before wilderness protections were created, and they serve as priceless traces of our forest history.

What would it take?

How can any of this ever happen… new trails, new trailheads, restored lookouts? Especially in the current political environment? That’s the inevitable question, of course, as the current administration in Washington continues their dismantling of our federal agencies and threatens to sell off our public lands.

My optimism comes from past cycles of trail building that have always come in waves, and my belief that a renewed focus on recreation and conservation is around the corner.

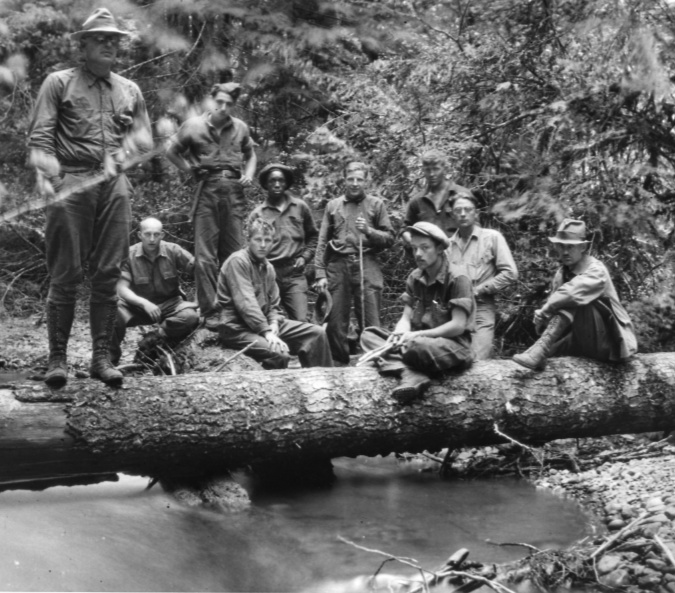

CCC trail crew working in the Mount Hood National Forest in the 1930s

Our greatest era of trail building came in the 1930s, thanks to New Deal job creators like the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and Works Progress Administration (WPA). These programs were a direct result the economic calamity of the times, and a willingness of Americans to reinvent government on a grand scale. The majority of the trails we enjoy today were built (or rebuilt) over just one decade when these programs were in full swing. World War II brought an end to the CCC and WPA, but the spirit and success of these programs remain on full display on public lands throughout the country.

A lesser-talked about golden era for trails came in the 1970s, and it, too, followed a period of social turbulence and unrest in the 1960s. While it’s true that logging on federal lands was hitting its peak at that time, it was also the case that new trails were being built by the Forest Service around the country. The Youth Conservation Corps (YCC) was created in August 1970 as an updated version of the CCC to help with this work, and signed into law by President Nixon, no less! The YCC still exists today, though somewhat scaled back from its 1970s heyday.

Today’s trail along the Hot Springs Fork to Baby Hot Springs was one of hundreds rebuilt by the CCC in the 1930s and further improved by the YCC in the 1970s

Flash forward to 1993, when AmeriCorps was created as part of the National Community and Community Trust Act, bipartisan legislation that has enabled millions of young people to gain experience and find direction in their lives in the three decades that have followed. In Oregon, this includes trail work on some of our most iconic trails, including the Timberline Trail.

While these programs and our agencies who administer them are under attack from the current administration, only Congress can create government programs and fund them. So, while are in an unprecedented time of belligerence toward the very idea of democracy and self-governance, it’s also true that these programs (and the country) will survive this ugly era. Why? Because they are popular and represent a minimal expense in the larger federal budget.

Eugene-based Northwest Youth Corp partners with AmeriCorps in their young adult leaders program. I ran into this group on the Timberline Trail one evening, where they were relaxing at camp after another day of trail work. When I offered to take a group portrait, their pride was overwhelming: they dropped everything and ran to get their hardhats and tools. It was a memorable encounter more than 15 years ago, and I’m certain their experience continues to enhance and shape their adult lives

That’s where my optimism is grounded. You wouldn’t know it from what is unfolding in our nation’s capital right now, but Americans aren’t nearly as divided as opportunists like the current president and his supporters seek to project. Access to our public lands is considered a sacred right by most Americans, across the political spectrum, and already the public is strongly objecting to the direction this administration has taken. When the impacts of the recent job cuts at the Forest Service and other land agencies begin to be felt over the coming months and years, it will be a real wake-up call, especially to the rural communities where most of these jobs are based.

The truism “you don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone” perfectly captures our very human tendency to take things for granted when they are going well– until they aren’t and we’re forced to reconcile with our role in what we’ve lost. I’m confident that we’re not only at that moment, but also to a historic degree that rises to the level of the 1930s and 1970s activism and reforms. Trails will be part of that, along with a renewed vision for public lands.

Trailkeepers of Oregon (TKO) and the Hidden Wilderness

I would be remiss if I didn’t include mention of the work Trailkeepers of Oregon (TKO) has begun in the Hidden Wilderness. TKO began sending volunteer crews here a few years ago to begin chipping away at the backlog of maintenance and the impact of recent fires on the trail system. In 2024, that work focused on the beautiful Dickey Creek Trail — the northern route into the wilderness that would be extended with the proposal in this article.

The plan was for TKO was to continue their work going forward, eventually restoring the larger trail network In the Bull of the Woods and Opal Creek wilderness areas, where crosscut saw expertise and backcountry crews are required under the Wilderness Act.

TKO volunteers reopening the burned section of the Dickey Creek Trail in 2024

The budget freezes and staffing cuts under the new administration has changed that. Among the fallout from the haphazard cuts to our public agencies is not only the loss of core agency staff for critical functions like firefighting, but also staff who empower volunteers who do the bulk of the trail maintenance and construction in today’s National Forests.

While we navigate out of the current political moment, the impact of the current staff cuts is real. Recreation programs at the Forest Service had already been running on fumes since the 1990s, so there really was no “fat” to trim, as much as the administration would like us to believe. The result has been a devastating loss in both human capacity and institutional knowledge within the Forest Service and other federal land management agencies. Unfortunately, it will takes many years to rebuild them once this storm is behind us.

TKO volunteers clearing logs from the lower Dickey Creek Trail with crosscut saws in 2024

But the current problem extends to non-profits like TKO who have contracts with the Forest Service to lead volunteer trail crews. The administration has frozen many of the small grants used to fund these contracts. This has put TKO and other trail-oriented non-profits at risk, so now is a great time to send some extra support to help bridge the gap:

Filling the gap will allow TKO continue to care for trails on Mount Hood and in the Gorge, despite the current uncertainty in Forest Service grants. It’s also form of resistance, since the value of spending time in nature on our public lands seems to be a foreign concept to this regime. And if you’re already stepped up to support TKO, thank you!

There is a saying “In the good times, plan for the bad, and in the bad times, plan for the good” that applies to this moment. Yes, there is much work ahead in keeping our trails open and ensuring that our public lands remain public, but we should also keep dreaming about those better days ahead when we can once again go big on trails and recreation in WyEast Country. That day will come!

And if you’ve read this far, thanks for hanging in there on what became a rather lengthy and unwieldy article! I appreciate your patience and, as always, thanks for stopping by!

_______________

Author’s Obscure Postcript…

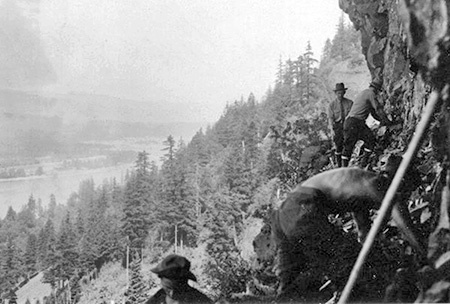

As you probably noticed, I included a few grainy images in this article from a 1981 backpacking trip into the Hidden Wilderness with my college roommate Dave. We took his early 70s Toyota Carolla wagon up the bumpy road to the Dickey Creek Trailhead while dodging log trucks, as there was very active logging at the time. For the next four days we hiked, swam, explored, fished and took in the views.

They don’t make ‘em like this anymore… and yes, I still have this camera!

However, it wasn’t until decades later that I discovered an undeveloped 126 film cartridge in this old camera that I carried on hikes in those days. I sent it off to be developed, and sure enough, it was filled with exactly 12 images from that trip – one complete roll. I had graduated to an Olympus OM-1 SLR camera shortly after that trip, and had forgotten about the roll of film left in the old Kodak Instamatic!

These grainy photos are priceless to me now, and it was fun to find a purpose for them in this piece!

_______________

Tom Kloster | June 2025