One of the memorable highlights along the Timberline Trail is the starkly beautiful section between Gnarl Ridge and Cloud Cap, high on the broad east shoulder of the mountain. Here, the trail crests its highest point, at 7,335 feet, as it traverses the tundra slopes of Cooper Spur more than a thousand feet above the tree line.

However, the spectacular elevation of the Cooper Spur section is also its Achilles heel, since hikers attempting the Timberline Trail must cross a series of steep snowfields here. In most years this entire section is snowed in through late July, and some sections of trail appear to be permanently snow-covered.

The trail builders constructed a series of huge cairns to mark the way through this rugged landscape, yet the snowfield crossings continue to present both a risk and route-finding obstacle to most hikers, especially in early summer. The Timberline Trail continues to draw hikers from around the world in ever-growing numbers, so an alternative route seems in order to ensure that the around-the-mountain experience continues to be world class for all visitors.

The Proposal

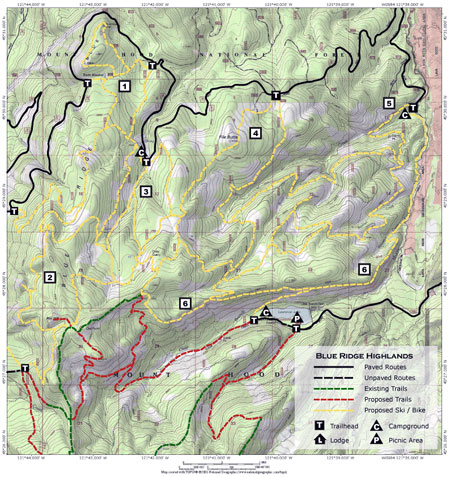

To provide a more reliable alternative for this segment, a new, parallel trail is proposed as part of the Mount Hood National Park Campaign. The new route would be about a mile to the east, at roughly the 6,200’ level, just below the tree line. For early season hikers, or simply those not up to the rugged combination of elevation, rock and snow on the existing trail, this new route would provide a more manageable alternative.

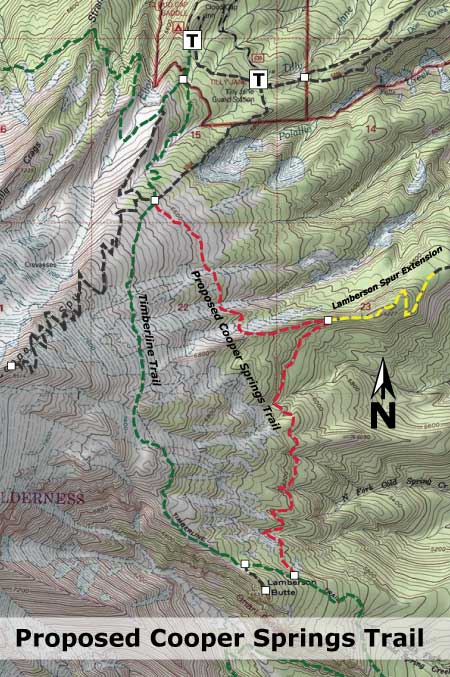

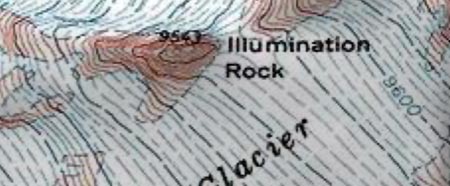

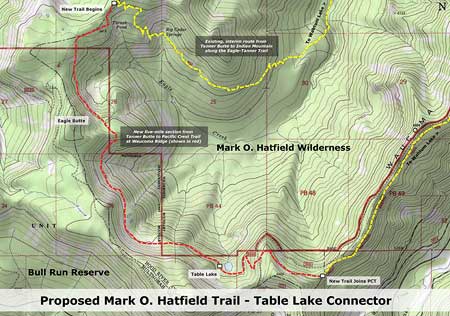

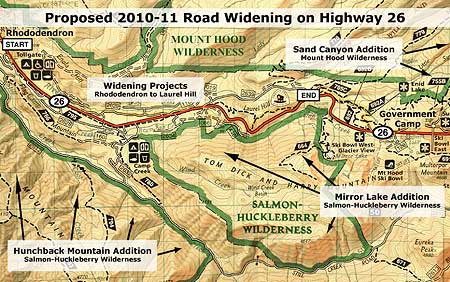

This new 3.5-mile route would still connect Cloud Cap to Lamberson Butte, but at a lower elevation. As shown on the map below, the proposed Cooper Springs Trail (in red) would depart from the current Timberline Trail (in green) at the current Cooper Spur junction on the north, and rejoin the Timberline Trail just below Lamberson Butte, to the south.

This option would add about a half-mile to the around-the-mountain trip, but would also save about 800’ of elevation gain, as measured in the traditional clockwise direction on the Timberline Trail. In fact, the new Cooper Springs Trail would actually drop 200’ in elevation from Cooper Spur Junction to Lamberson Spur.

This new trail wouldn’t be a formal segment of the Timberline Trail, but simply a hiking option, just as other parallel routes to the Timberline Trail already allow at Umbrella Falls, Paradise Park, Muddy Fork and Eden Park.

Today, these complementary routes along other sections of the Timberline Trail not only allow for interesting loops and less crowded conditions for hikers, they also provide detour options when trail closures occur — as happened recently along the Muddy Fork, where hikers were able to use a parallel route to avoid washouts on the main trail.

What Hikers Would See

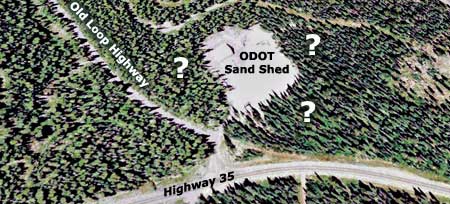

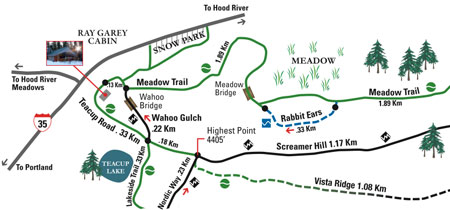

The northern segment of the new Cooper Springs Trail would make a gradual descent from the existing 4-way junction of the Cooper Spur, Tilly Jane and Timberline trails to the tree line, curving through a series of small headwater canyons that eventually feed into Polallie Canyon. This section would cross the first of several small streams along the new route.

The northern section of the new trail from above the Timberline Trail, as viewed from the slopes of Cooper Spur.

Soon the new route would cross a sharp ridge, where under this proposal it would intersect with an extension of the Lamberson Spur Trail. This trail is an odd anomaly: the route is marked and maintained where it leaves the Cold Spring Creek Trail, but mysteriously dies out on a ridge about a mile below the tree line. A few adventurous hikers continue cross-country from this abrupt terminus to the Timberline Trail each year, but under this proposal, the Lamberson Spur Trail would be formally connected to the new Cooper Springs Trail. This new segment is shown in yellow on photo schematic, above.

Extending the Lamberson Spur route to the new Cooper Springs Trail would entail about a mile of new trail, but would be an important piece in linking the new Cooper Springs route to the existing network of trails along Cold Spring Creek and Bluegrass Ridge, to the east. Together, this network of trails could provide an important, less crowded overnight or backpacking experience than is possible on the more heavily visited sides of the mountain.

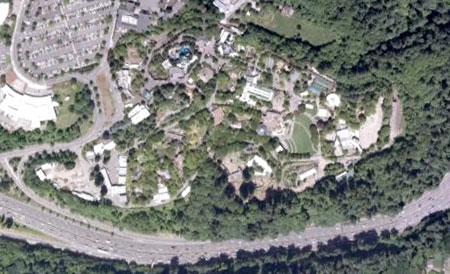

Beyond the proposed Lamberson Spur junction, the middle section of the new Cooper Springs Trail would pass through an especially interesting landscape. Here, a series of dramatic cliff-edged bluffs and talus slopes frame the view of Mount Hood and Cooper Spur, looming above, while the trail would cross through groves of ancient mountain hemlock.

The middle section of the new trail would traverse a series of little known canyons and cliff-topped bluffs below Cooper Spur.

This section of the new trail would also provide a close-up look at the aftermath of the Gnarl Fire, which burned a large swath of forest along the eastern base of the mountain in the summer of 2008.

At one point, the fire made headlines when it threatened to destroy historic structures in the area, narrowly missing the venerable Cloud Cap Inn. Though the trail would traverse above the burn, it would allow hikers to watch the recovery phase of the fire cycle unfold on the slopes, below.

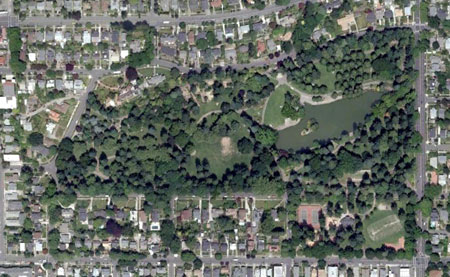

Finally, in the southern section the proposed Cooper Springs Trail would traverse through dozens of rolling lupine meadows, gnarled stands of whitebark pine and mountain hemlock and unique views of the massive east face of Mount Hood and the surrounding wilderness.

The southern section of the new trail would weave through a series of little-known alpine meadows, near Lamberson Butte.

In this section, the proposed trail would traverse the slopes of Cooper Spur at the point where a series of tributaries to Cold Spring Creek emerge and flow eastward through a maze of steep canyons. The springs are continuously fed by several permanent ice fields on Cooper Spur, and thus would be a reliable water source for hikers — and are also the namesake for the proposed trail.

The new route would then rejoin the Timberline Trail just below Lamberson Butte.

What it Would Take

The proposed Cooper Springs Trail (and Lamberson Spur extension) would be entirely within the Mount Hood Wilderness, and thus must be built without the add of motorized equipment.

Normally, this presents a major obstacle to trail construction, since a typical trail requires the removal of trees and vegetation down to mineral soil — a formidable task in the rainforests of the western Cascades, even with the aid of chainsaws and power tools. However, the slopes of Cooper Spur consist mostly of soft, sandy soils, loose rock, scattered trees and open meadows, so construction of the 3.5 mile trail would be much less cumbersome with hand tools here than in other parts of the forest.

There are a number of organizations that might be interested in helping build the trail, but perhaps the most promising would be the Northwest Youth Corps, an organization that has sent crews of young people to restore wilderness trails around Mount Hood for many years.

Finally, it would take a renewed commitment from the Forest Service to expand the trail network around the mountain, and this is the largest obstacle. The agency has been doing just the opposite for many years, allowing trails to fade into oblivion for lack of basic maintenance.

But this is also where you can help: the Forest Service has the funding to provide more trails, yet needs strong public support to make trails a priority in agency budgets. Buying a forest pass simply isn’t enough, unfortunately.

Make your opinion known, and don’t accept the “lack of funding” explanation. Instead, take a look at this comparison of funding for Mount Hood and a couple of well-known national parks, and simply ask that YOUR forest to be managed with trail recreation at the top of the priority list.

How can you contact them? Just click here to send them an e-mail!