Spring has arrived in the Columbia River Gorge, and as we explore among the unfurling fern fronds and explosion of wildflowers, we will also be keeping a wary eye out for a pair of nemeses who also make the Gorge their home: poison oak and ticks! Sure, there are other natural hazards out there, but poison oak wins the prize for quiet ubiquity while ticks are actually OUT TO GET YOU!

Naturally, a lot of mythology exists on both fronts, and I’ve previously debunked poison oak myths. In this article, I’ll tackle the kitchen remedies and common folklore that abound for ticks. The Centers for Disease Control is my primary source for information on the subject, and their tick resource pages are worth a visit for anyone who spends time in tick country. I’ve also relied on the Companion Animal Parasite Council (CAPC) for the best advice on managing ticks on our pets.

The one to watch for: Western Black-Legged Tick (Source: Public Health Image Library)

While poison oak can trigger a miserable rash, it’s rarely a serious health risk. Ticks are different. While their bites aren’t usually painful, these tiny members of the arachnid family (they’ve got eight legs – count ‘em!) can also transmit several blood-borne diseases, most notably the bacterium that can cause Lyme disease in humans and animals.

Western Black-Legged Ticks (from left) in nymph stage, adult male and adult female (Source: California Health Dept.)

While the potential for Lyme disease exists in just two tick species, all ticks have the potential to carry disease, and should be treated with equal caution. So, with that creepy-crawly introduction, here are ten common tick myths, debunked:

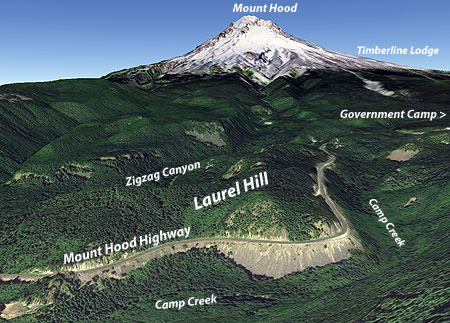

Myth 1: Ticks only occur in the Eastern Gorge

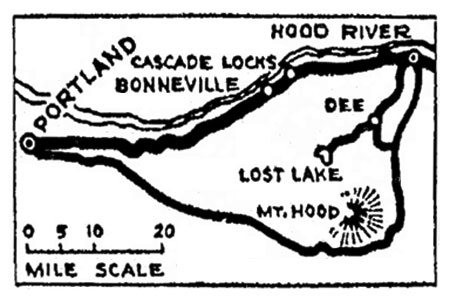

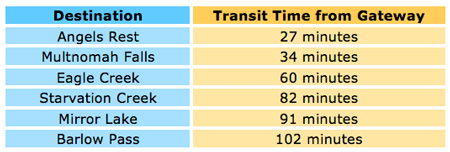

False. While it’s true that ticks are VERY common in oak and pine savannah of the Eastern Gorge, they have been reported throughout the Gorge, though in decreasing numbers as you head west. Based on my own experience, the tick population grows steadily as you head east of Bonneville.

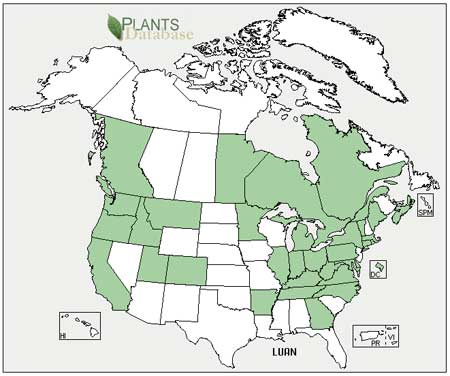

The CAPC forecast for tick exposure in 2013, with hot spots Hood River and Clackamas counties and Southern Oregon (Source: CAPC)

Ticks are found throughout much of Oregon, as it turns out, but generally not in the prolific numbers as we find the Gorge. The CAPC map (above) shows the 2013 tick exposure forecast by Oregon county, with Hood River and Clackamas counties as a expected hot spots in northern Oregon and Jackson and Josephine counties showing higher risk in southern Oregon.

So, while you may have hiked in the “safer” areas of Gorge, it’s always good idea to do a tick check when you get home, no matter where you hiked. But if you’re hiking east of Bonneville, then it’s a good idea to expect ticks and take some precautions.

Myth 2: Ticks die in winter

False. Though tick populations generally decline in winter, in mild winters (such as the past one) ticks in the Gorge can continue to grow and thrive in the outdoors. When the temperature drops below freezing, ticks simply become inactive and burrow into leaf litter, emerging when conditions improve.

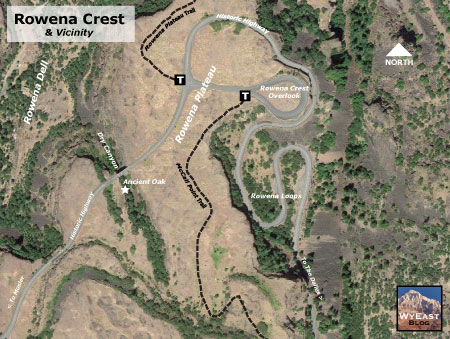

Year-round tick country: the Columbia River from the terraced slopes above Rowena Crest

Tick research in the Northeast suggests a threshold temperature of 38º F and above for ticks to become active, though no research is available for the Pacific Northwest. But it’s safe to assume that you can encounter active ticks year-round in the Gorge in all but the coldest weather.

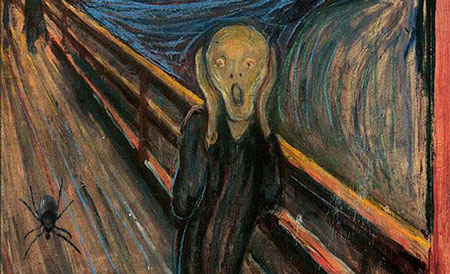

Myth 3: Ticks should be removed using a lit match

“Just light a match, blow it out, and put the hot tip on the tick to make it angry, and it will back right out!”

“I just used WD40 on a cotton swab to remove a tick from my 3 lb Chihauhau.”

(advice from the internet)

..or… paint thinner, dish soap, kerosene, nail polish remover and Vaseline. All of these folklore solutions have spread far and wide in the age of the internet, along with cult-like followings to defend them!

The idea that Vaseline or WD-40 will suffocate the tick and nail polish will kill it with toxins or cause it to detach on its own is sketchy, at best. Worse, these folk remedies could cause the tick to disgorge its contents into your bloodstream — exactly what you’re trying to avoid!

Instead, ticks should be gently pulled from the skin with tweezers or a custom tool for removing ticks (more on that later).

Myth 4: If parts of the tick break off when removing it, you have to dig them out to prevent Lyme Disease

Advice on this one varies: some sources recommend removing all parts of the tick to prevent a secondary infection, while others argue that you’ll do yourself more harm trying to dig them from your skin. But if you remove the living tick within 24 hours, you’ve likely removed any risk of infection with a tick-borne disease, even if you didn’t get the entire tick.

The safest bet is to check with your doctor if you find yourself in this situation. Even better, be sure to remove the tick properly, and you will be much less likely to break off any tick parts (again, more on that later).

Myth 5: Ticks can re-grow their bodies if the head is still intact

Headless is dead… even for the mighty tick!

False. This bit of folklore probably comes the (admittedly creepy) fact that the abdomen of a tick that has become engorged after several days of being attached to a host can become alarmingly large. Or maybe that some snakes and lizards can re-grow their tail? But a beheaded tick is just that, and can’t survive.

Myth 6: A hot, soapy shower will remove any ticks

Partly true. Ticks can survive a shower – or even a bath — and happily stay attached to your skin, but a shower can wash away ticks that haven’t attached yet. If you’ve done a visual tick check before jumping in the shower, it’s not a bad idea to do another fingertip check with the aid of soap and water, feeling for small bumps along the skin.

A fingertip check is especially helpful in finding small, immature ticks in the nymph stage, when they are about the size of the head of a pin. They often go unnoticed until fully engorged, and are therefore responsible for nearly all of human Lyme disease cases, according to the American Lyme Disease Foundation.

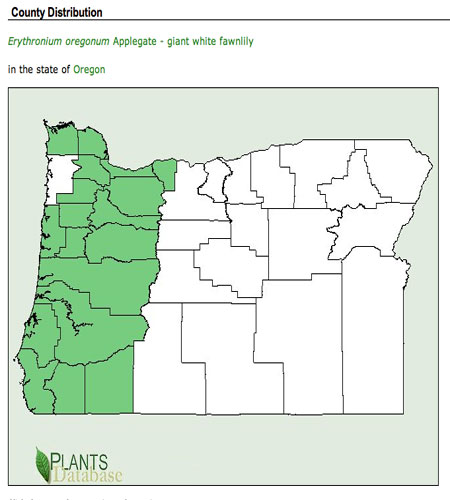

Myth 7: Ticks in Oregon don’t carry Lyme disease

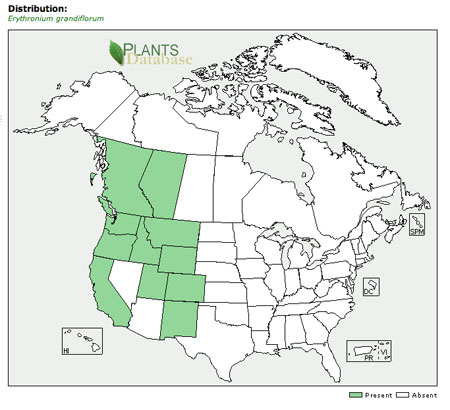

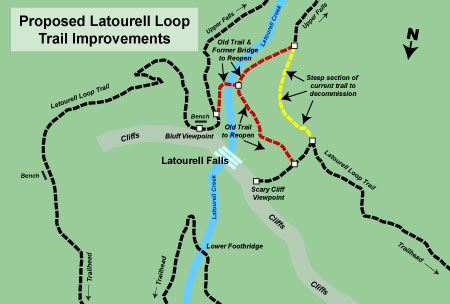

Partly true. While not common in Oregon (yet), Lyme disease is here, with Oregon falling in the “moderate” range for disease risk in 2013, according to the CAPC (see map, below). However, in the Western states, Lyme disease is only transmitted through the Western Black-Legged Tick, just one of several tick species found here.

The 2013 Lyme Disease forecast by the Companion Animal Parasite Council puts Northwest Oregon in the moderate risk range (Source: CAPC)

Though small, Oregon’s Lyme-carrying ticks are noticeably larger than the only other species known to the disease (found in eastern states), so they are easier to spot and remove. Small comfort, to be sure, but it does make coping with ticks a bit less troublesome in this part of the country.

A caveat to that size difference is that our Lyme-carrying ticks in the immature phase — known as a “nymph” are still very small, so warrant extra care during the spring and early summer and nymphs are most common. Nymphs spend most of their time on the ground, and generally feed on small animals as a result, but it’s still a good idea to look closely for nymphs when you check for ticks.

Myth 8: Only people can get Lyme disease

False. Lyme disease was first identified as a tick-borne illness for humans in 1978, and the actual cause (a bacterium) of the illness wasn’t discovered until 1981. By 1984, Lyme disease had been discovered in dogs, and soon after, in other domestic animals, including horses and cats.

In the Northeast, dogs with Lyme disease have become commonplace, to the point that some states have stopped tracking the infectious because of the flood of reports to veterinary clinics.

Oh, the injustice! The sleepy villages of Lyme and Old Lyme, Connecticut have the unfortunate distinction of having a tick-borne disease named for them..!

The test for Lyme disease in dogs takes just a few minutes, and dogs testing positive are generally treated with a 30-day regiment of antibiotics. For most dogs, visible symptoms of the disease are the same as for humans: swollen joints, lethargy, and in a small percentage, kidney failure. Veterinary clinics in the Northeast are now offering a Lyme disease vaccination for dogs in response to the increased rate of infection.

Myth 9: Lyme disease is always marked by a bullseye rash

False. While Lyme disease in humans typically causes a red rash to expand from the site of the tick bite, creating a “bullseye”, this distinctive rash only occurs in 70-80 percent of cases, according to CDC.

The classic Lyme disease bullseye (Wikimedia)

Usually, a tick must remain attached for a minimum of 24 hours to transmit Lyme disease, so if you remove a tick promptly, it’s soon enough to avoid an infection risk. If you’re not sure, or know that a tick was been embedded for more than 24 (even without the bullseye rash), it’s probably a good idea to check with a doctor about starting antibiotics as a precaution.

Myth 10: Every tick bite carries the possibility of Lyme disease

False. Most tick species do not carry Lyme disease. Only ticks in the genus Ixodes carry the bacteria B. burgdorferi which causes the disease. This includes the Deer tick (Ixodes scapularis) in the Northeastern states and the Western Black-Legged tick (Ixodes pacificus) in the West.

In Oregon, the adult Black-Legged tick measures about two-thirds the size of the more common Wood (or “dog”) tick (Dermacentor variabilis), which frequent similar habitat. However, while the Wood tick doesn’t transmit the Lyme bacteria, it does carry other diseases (including Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever), so the same care in managing ticks applies, no matter the species.

Black-Legged tick (left) compared to common Wood tick (right)

The risk of Lyme infection from a tick bite is estimated at 1-3 percent, so very low — but still cause for caution. Why? Because left untreated, Lyme disease symptoms may progressively affect joint, heart and central nervous system health. In most cases, the infection and symptoms are eliminated with prompt use of antibiotics. Delayed diagnosis and treatment can make the disease more difficult to treat and risk lasting disability, so it’s a serious concern.

_______________________________

When you’re in tick country…

Ticks are found where they can reliably attach to deer, livestock, other mammals, ground-dwelling birds and even lizards. Some of the most productive tick habitats in the Columbia Gorge are oak woodlands and areas of vegetation at the edge of forests, along forest hiking trails and game trails and in grassy meadows. They are also common in power line corridors that cut through forests, around campgrounds and in tall grass along roadways.

While ticks are definitely stalking YOU, it’s not an active pursuit. Instead, they wait on vegetation for passing hosts to come along. Ticks can detect hosts by sensing carbon dioxide, scents and vibrations from movement of their hosts. They can sometimes be seen at the tips of grass blades or plant leaves “questing.” This is a behavior in which the tick extends waving front legs ahead of an approaching host, looking to catch a ride!

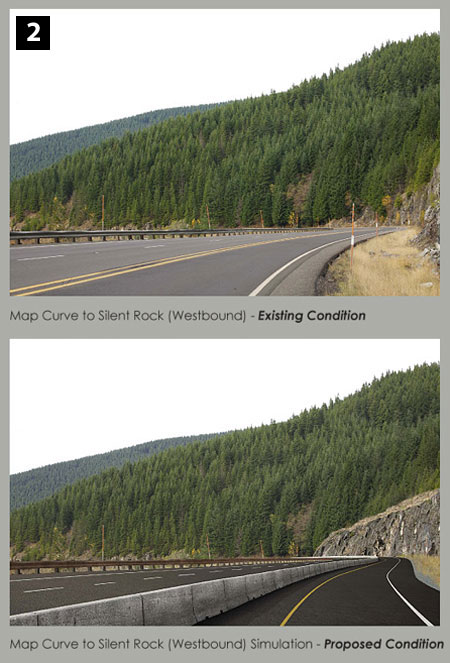

Sure, it looks funny! But it’s a proven practice for tick prevention

When you’re in tick country, wear light colored long pants and long-sleeved shirts. Tuck pant legs into socks (see photo, above) and shirts into pants to close off points easy of entry at tick-level. This not only makes it harder for a tick to make its way to your skin, it also allows you to better spot ticks on your clothing, and simply brush them off.

Walk in the center of trails, and avoid brushing against tall grass or undergrowth along the trail. If you stop, sit on rocks or logs, not in grassy areas, and periodically brush your legs and sleeps to feel for ticks on your clothing. These simply practices not only help prevent ticks from going for a ride, they also help you avoid poison oak, so you get a twofer for these prevention basics!

Materials treated with DEET or permethrin are proven to repel and eventually kill ticks. Of the two, permethrin is the most effective and long lasting. This pesticide can be used to treat boots, clothing and camping gear and remain protective through several washings. It is toxic to cats, however — even from contact with recently treated clothing — so must be used with care!

DEET (left) is easier to use but Permethrin (right) is more effective for ticks

DEET products are also widely available, and can be applied to both your skin and clothes (with some fabric limitations). Deet might be a good option if you’re hiking in warm weather and less inclined to cover up with clothing.

After your hike…

After you’ve been hiking in tick country, here’s an easy checklist to follow:

1. Check clothing for ticks when you return to the trailhead. Ticks may be carried home and into the house on clothing, so check before you get into the car. When you get home, be sure to immediately put clothing in the wash, then the dryer to take care of any stowaways you might have missed. Clothing that can’t be washed can go directly into the dryer, where an hour on high heat will kill any ticks.

2. Do a full body check. Before you get in the shower, use a hand-held or full-length mirror to view all parts of your body including your scalp, behind your ears and… gulp… around your privates! A thorough check should take about 30-45 seconds. Kids should be checked by parents!

3. Shower right away. Showering washes away un-attached ticks that you might not have spotted, and has been shown to reduce your risk of getting Lyme disease as a result. It also gives you an opportunity for a thorough fingertip tick check with soapy fingers.

4. Do another full body check. After a shower, repeat the full body check with a mirror.

You should continue to watch for ticks for a couple days after spending time in tick country, to ensure that you haven’t missed a tick.

What to Do if You Find an Attached Tick

Remove an attached tick as soon as you notice it with tweezers or a special tick removal tool. Grasp a tick as close to your skin as possible, pulling it straight out — and don’t “unscrew” the tick, as suggested in many folk remedies, as you’ll likely pull the head off the tick!

The tick remover kit shown below is one of the best available, and far superior to tweezers, as it involves no squeezing when pulling a tick — thus lessening the chance of infection or breaking off the head. This kit consists of a simple, forked spoon for lifting the tick out and a tiny magnifier for use in the field. I carry this kit in every one of my packs — it’s inexpensive, and easily found in outdoor stores or online.

The excellent Pro-Tick Remedy system makes pulling ticks a breeze!

Once a tick is out, wash the wound with soap or alcohol and monitor it for a day or two for signs of infection. Most tick wounds will heal up quickly, with no sign of the bite after a couple days.

It’s always safe to watch for any signs of tick-borne illness after you’ve been bitten, such as rash or fever in the days and weeks following the bite. If you suspect you have symptoms, see your doctor.

Ticks and your dog…

Dogs are very susceptible to tick bites and diseases, and of course, hikers love to take their dogs into the Gorge. While vaccines protect dogs from some tick borne diseases, they don’t keep your dog from bringing ticks into your home.

There are several things you can do to protect your dog from ticks. Most obvious is to simply leave your dog home when venturing into areas known for ticks — and that includes areas in the Eastern Gorge. But if you do take your dog into tick country, there are some preventative steps that will greatly reduce the chance of a tick attaching to Rover.

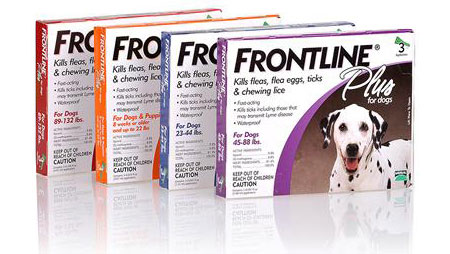

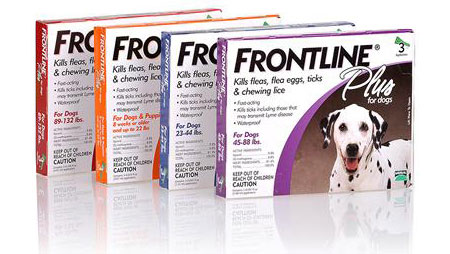

The most common (and simplest) solution for preventing ticks on your dog is a once-per month, non-prescription insecticide treatments available from most veterinarians, online or from pet stores. The best-known options are Frontline Plus™ and Advantix™.

Frontline Plus comes in doses adjusted for the weight of your dog, and is applied from a hard-to-open, somewhat awkward-to-use dropper that can spill onto your hands

The key ingredient that makes both Frontline Plus™ and Advantix™ effective on ticks is premethrin, the same common, widely-used pesticide used to treat clothing for ticks. Be very careful if you have cats in your home, however, as premethrin can be fatal to cats, whether inadvertently administered or even by exposure to a recently treated family dog. Both treatments are applied along the spine, beginning at the back of the neck and moving toward the tail, and are effective for up to one month.

These products should prevent ticks from attaching to your dog — and even if one does, the premethrin ingredient would likely kill the tick, eventually. But these products don’t prevent ticks from going for a ride in your dog’s fur, so it’s always a good idea to inspect your dog at the trailhead, using a brush, before loading up and driving home.

Advantix has the same premethrin ingredient as Frontline Plus, but is easier to administer with well-designed tubes that keep the product off your hands

Tick bites on dogs can be hard to detect, as tick borne disease symptoms may not appear for up to three weeks after a tick bite. Call your veterinarian if you notice changes in behavior or appetite in you think your dog might have been bitten by a tick.

Tick! Tick! (…but don’t panic…)

Okay, so this article might have you nervously scratching your legs on your next hike and seeing every black speck on your boots as a TICK! But don’t let these little blood suckers get you down! Sure, they’re annoying… and kind of creepy. But the basic precautions outlined above are easy to build into your hiking routine, and more than enough to give you peace of mind when you’re out on the trail.

If you DO find a tick that has managed to attach to you, and you’re creeped out by the thought of pulling it — or can’t reach the tick yourself — simply head for the doctor’s office. They will take care of it for you, and the chances of any complications are extremely small. Even if you have pulled the tick, and are feeling sort of queasy about it, go to the doctor (with the tick). It will be worth the peace of mind.

For a lot more information on ticks (if you aren’t adequately freaked out by now), check out the Centers for Disease Control tick resources.

Then, by all means, get back out on the trail, ticks (and poison oak) be damned!