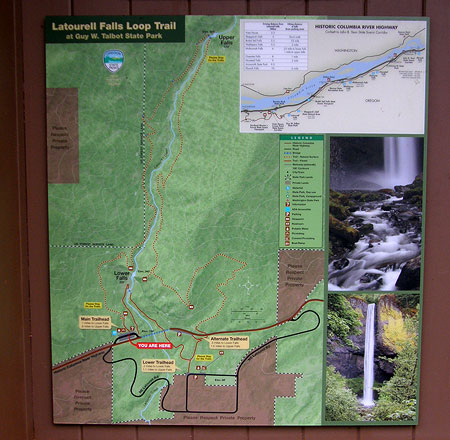

In the first part of this article, I focused on recent improvements that have greatly enhanced the Historic Columbia River Highway wayside at Latourell Falls. This article looks at the balance of Guy Talbot State Park, where a number of improvements are needed to keep pace with the ever-growing number of visitors who now hike the Latourell loop trail year-round.

Improving the Loop Trail

Hiking the loop in the traditional clockwise direction from the wayside, the first stop is bench located a few hundred yards up the trail. This memorial bench was donated by the Sierra Club, and though it’s not a great architectural fit for the area (a rustic style would be more appropriate), it’s still a welcome resting spot for casual hikers.

Not coincidentally, the bench faces a lovely view of Latourell Falls, but there’s a story behind the view, as someone has made the effort to do some “scene management” for photographers. Take a look at the photo below, and you can appreciate the waterfall scene in its graceful glory, framed by firs and moss-covered maples. But a closer look reveals a sawed-off stump with a fresh cut. Why here? Because a trail steward (authorized or otherwise) trimmed off the broken shards of a maple that split off in an ice storm a few years ago — leaving a sore thumb that marred this classic view. You can see in these after/before comparisons from now and in 2010:

If this was sanctioned “scene management” pruning, then kudos to the State Parks folks for putting classic views on their maintenance list. If this is a guerilla effort by a frustrated photographer, then perhaps State Parks managers will take note, and keep this view intact..!

Moving up the loop, the trail soon approaches a heavily trampled bluff above Latourell Falls. Here, the first apparent problem is a decades-old shortcut at the first switchback. A sign begs hikers to stay on the trail to protect “sensitive plants”, but so far, the boots are winning, despite logs and debris purposely scattered across the shortcut.

Tossing more logs across this shortcut might help, but borrowing an idea from the beautiful new stonework at the trailhead (or recently built stonework along the Bridal Veil Falls trail), and adding a rustic stone retaining wall here to corral traffic would be a nice option that would have lasting value.

The viewpoint atop the well-worn bluff is really starting to show its age. The 1950s-vintage steel cable fence and mix of concrete and steel pipe posts were never a good aesthetic fit for the Gorge, but more importantly, they’re not doing anything. Visitors have recently pushed a scary boot path past the fence, and down to the brink of Latourell Falls (shown below), so a near-term fix is in order.

The trail at the overlook has already been stomped into a wide “plaza” of sorts, and that would be a good design solution here, with a stone wall replacing the rickety old handrail. A layer of crushed gravel (another design feature of the recent improvements at Bridal Veil Falls) would further help minimize the mud slick that forms in wet months.

The lone (and beleaguered) wood bench at the overlook is well-used, and a redesign should include two or three places to sit and admire the view. For most visitors who venture beyond the lower falls overlook, this bluff above the falls is the turnaround point.

Adding a stone wall to better define the overlook would help curb foolhardy visitors from following the boot path to the falls brink. However, the overlook also needs some vegetation management in order to simply maintain the view back down to the trailhead — this is what most hikers who push beyond the handrails are looking for, after all.

A pair of reckless visitors in flip-flops spotted in 2010 at the bottom of the dangerous boot path, tempting fate…

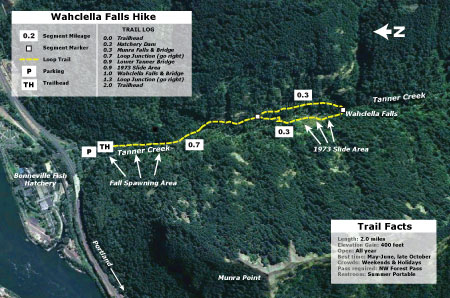

A few steps beyond the bluff overlook, an unmarked trail forks to the right, descending to Latourell Creek. At first, this seems like another informal boot path, but a closer look reveals a well-constructed trail. In fact, this is where a lower loop once crossed the creek, connecting to the main loop where it returns (and is clearly visible) on the far side of the creek. This is an old idea that still makes sense, and should be embraced with a new bridge and refurbished connector trail.

In reality, hikers are already using the lower loop, though a series of slick, dangerous logs a few yards upstream from the brink of Latourell Falls serve as the “bridge”. Reconnecting and restoring these old trail segments would be a good way to provide a shorter loop for less active hikers, and also resolve this hazardous crossing that is clearly too tempting for many hikers to resist.

Bridge needed! This old trail and the sketchy log crossing are an accident waiting to happen — and also an opportunity to provide an excellent short loop for hikers.

Moving along the loop to its upper end, the Latourell trail has a few issues at Upper Latourell Falls that deserve attention in the interest of protecting the lush landscape from being loved to death. For many years, this upper section of the trail was only lightly used, but the proximity of Talbot State Park to the Portland Metro region and the family-friendly nature of this trail has clearly made the full loop a very favorite destination.

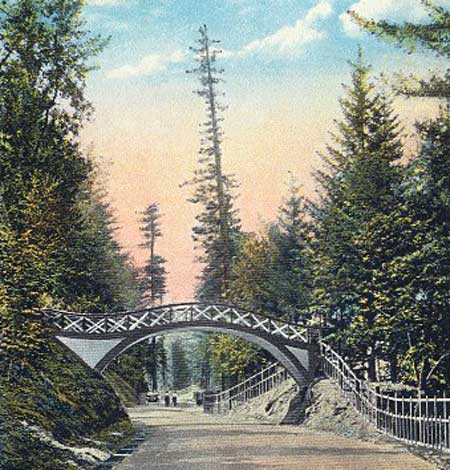

The trail approach on the east side of the falls is in good shape, but problems start to emerge on the west side of the footbridge. This is not coincidental, as an adventurous early trail once switch-backed up the slope on the west side, and led to a precarious bridge across the mid-section of the falls (shown below).

The location of this old trail was uncovered only recently. Century-old rockwork and obvious paths heading uphill from the falls have always hinted at an old trail, but a geocache has now been placed along the old path, drawing enough visitors up the slope to add some urgency to addressing the off-trail impacts here.

The best solution here is to embrace the lowest segment of the old path by repairing the stonework, or perhaps adding steps where a shortcut has formed, and provide hikers with that close-up view from behind the falls that is responsible for the bulk of the off-trail traffic (the hikers in the photo above are making this irresistible trip).

The upper sections of the old trail are much less traveled, and a simple solution here might be to simply ask the geocache owner to remove the cache. The cache risks not simply re-opening the old trail, but also bringing inexperienced hikers to the potentially dangerous rock shelf where the log footbridge once stood. If the geocache is removed soon, it’s unlikely that visitors would even notice the upper portions of this trail.

This precarious bridge spanned the upper tier of Upper Latourell Falls in the early 1900s (courtesy U of O Archives)

Turning downstream along the west leg of the Latourell loop, the trail passes a couple of spots where some TLC is needed. First, another potentially dangerous log crossing (shown below) has drawn enough traffic to form its own boot path.

It could be decades before this old log finally collapses into the creek, so a better plan is needed to stem the damage now. Sawing out the log seems possible, and is a job that could be easily in early fall, when water levels are at their lowest, and fire danger has passed. This might even be a job for volunteer trail stewards with crosscut skills.

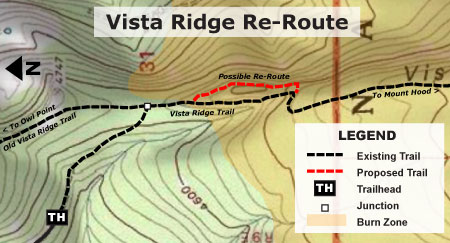

A bit further downstream along the west leg, the loop trail passes the old trail leading to the former footbridge (described previously). Here, the new trail launches uphill along a steep, slick segment built to bypass the bridge.

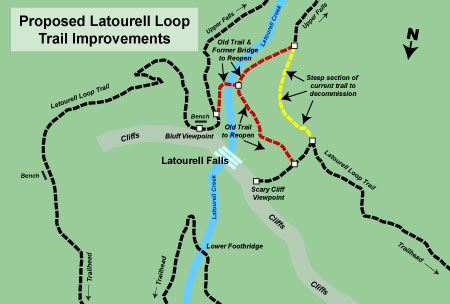

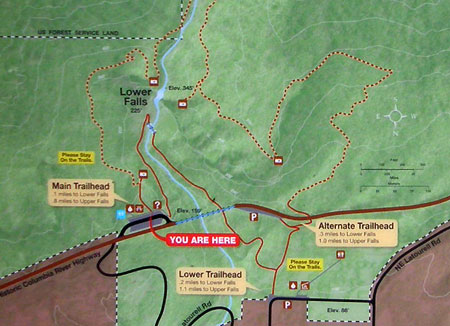

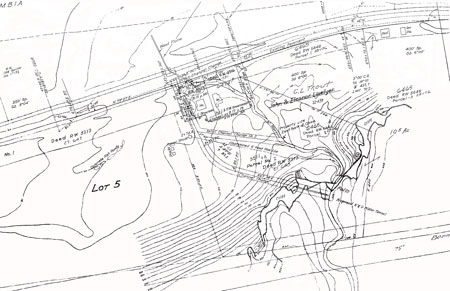

Reopening the old trail section (and adding a new bridge) would therefore have a spinoff benefit here: not only would a shorter loop be possible (and safe), but the short, badly designed new section of the current trail (shown in yellow on the map, below) could be decommissioned, with the main route using the old section of trail, once again (shown in red). This would be a terrific project for volunteers, including bridge construction.

(click here for a large map)

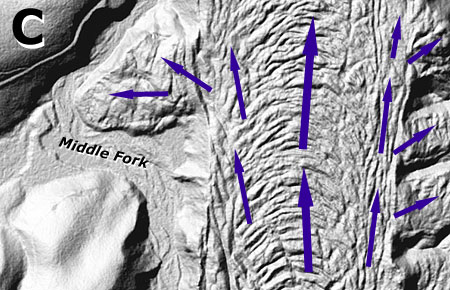

Another scary feature suddenly appears as the west leg of the loop trail curves above Latourell Falls: an old viewpoint spur trail heads straight down to a very exposed, rocky outcrop rising directly above the falls. The view from this exposed landing is impressive, but completely unsafe, given the thousands of families with young kids that walk this loop each year. There is no railing and no warning of the extreme exposure for parents attempting to keep kids in tow.

The safety hazards of the west overlook are twofold: certain death for someone slipping over the 280 foot sheer cliff to the north and a tempting, sloped scramble to the falls brink for daredevils and the foolhardy.

A simple solution could be a handrail or cable encircling the viewpoint, but a more elegant option would be a more permanent viewing platform in the stonework style of the improvements at the trailhead, serving both as a safety measure and to encourage visitors to comfortably enjoy the airy view.

Next, the loop trail curves away from the creek and out of Latourell canyon, passing an overgrown viewpoint (that probably deserves to be retired), then descending in a long switchback to the Historic Columbia River Highway.

Here, the route crosses the road, and resumes on an attractive path that suddenly ends in the Talbot State Park picnic area. Though a bit of searching gets most hikers to the resumption of the loop hike, some signage would be helpful here — both to direct loop hikers back to the main trailhead, but also pointing picnickers to trail to both the upper and main waterfalls.

Beyond the picnic area, the trail re-enters Latourell canyon and quickly descends to the base of Latourell Falls, the final area where loop trail improvements are sorely needed. At this point along the loop, we are within a few hundred yards of the main trailhead and wayside, so the crush of year-round visitors is evident everywhere — and thus the paved trail surface in this portion of the loop.

Most of the human impact is absorbed by the trail, but in recent years a messy boot path has developed along the west side of the creek, starting at the lower footbridge, and branching as it heads toward the base of the falls.

As it nears the falls, the boot path devolves into a web of muddy paths, where delicate ferns and wildflowers have been trampled

There isn’t a good way to convert this boot path into a formal spur or viewpoint because of the unstable slopes and visual impact it would create, so the challenge is how to best manage the off-trail activity. The simplest option would be an extension of the bridge hand-rail to block the boot path, making off-trail exploring a bit harder.

This mud patch at the east approach to the lower footbridge would make a perfect mini-plaza for visitors to spend time taking in the view

But there is also an opportunity to embrace the first part of the boot path, where a “mud plaza” of sorts has been stomped into the ground. This spot features one of the best angles for photographing the falls, after all, so a stone masonry mini-plaza with seating would be a terrific way to both discourage the off-trail travel, and give waterfall admirers an inviting place to stop and photograph the falls, out of the main flow of foot traffic.

Honoring Guy W. Talbot

One last bit of unfinished business at Talbot State Park is a debt of gratitude to Guy Talbot, himself. At the west end of the historic highway bridge, a large gravel pullout serves as overflow parking for this popular park. The loop trail crosses the highway near the pullout and in recent years, heavy use has turned this into an overflow trailhead, as well.

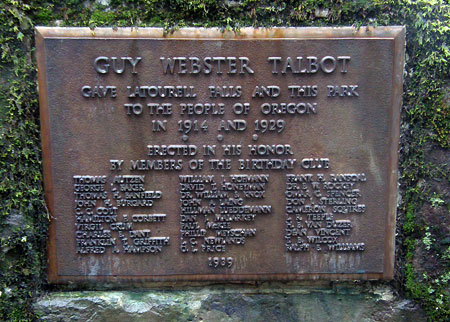

At first glance, it seems nothing more than a broad, gravel shoulder. But upon closer inspection, it’s home to the only real monument to Guy Webster Talbot — the man whose profound generosity spared Latourell Falls from some other fate, and gave us the park that we know today. After all, the property wasn’t simply an undeveloped tract of forest, but rather, Talbot’s beloved country home. He gave the place he loved most to all Oregonians, in perpetuity.

Few traces of Talbot’s home and the surrounding estate survive, so this would be the perfect spot for a third interpretive sign (the first two are on the east end of the bridge, at the refurbished wayside) focused on Talbot, and why he was such an important historical figure in history of the area.

The pullout, itself, could also be improved to become a more formal secondary trailhead for the loop, as well — perhaps not as substantial as the newly rebuilt main trailhead and wayside at the other end of the bridge, but something better than the pothole-covered pullout that exists today.

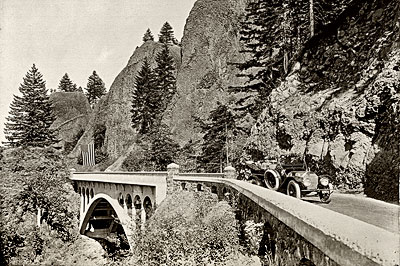

Finally, there’s one more interpretive opportunity near the Guy Talbot memorial: a tale of two bridges. One is the towering, 300-foot long Latourell Bridge along the old highway, to the east. The unique history of its construction in 1914 is a story that should be told, especially since visitors can walk both sides of the bridge on the beautifully designed, original sidewalks.

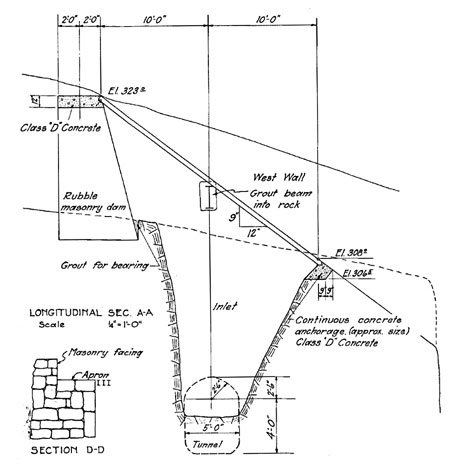

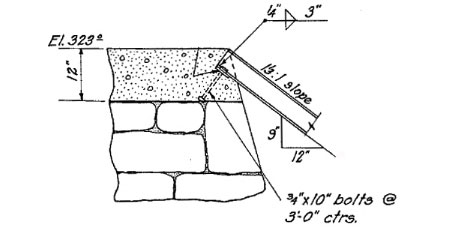

The second bridge is a curious phantom of history — a former footbridge that once connected the two halves of the Talbot property in an elaborate, Venetian-style arch. Though long gone, the footings for the bridge can still be seen, and are a reminder of the elegance of days gone by.

The good news is that both the Oregon State Parks and Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) are on a roll when it comes to enhancing the Historic Columbia River Highway trails and waysides. Many recent improvements to the Gorge parks and the old highway, itself, have already been completed in recent years, and more are already under construction.

Hopefully, polishing up the rest of the Latourell Falls loop and Talbot State Park can find its way into the State Parks and ODOT work program, too!

___________________________

Addendum: after posting this article, I heard from the owner of the geocache mentioned above Upper Latourell Falls. File this under the “small world” department, but it also happened to be someone I’ve known for many years, and who sets the highest standard for conservation ethics. Had I checked the cache ownership and known this, it would have erased any concerns about potential impacts the cache will have on the area. I now know it is in very good hands!

The cache owner also shared some numbers behind the cache that support that last point: only 50 users have logged it in the 3-plus years since it was placed, so not enough to have a noticeable impact on the terrain. Thus, the impacts that we’ve seen in recent years are likely just more of what we see elsewhere on the loop, where the crush of thousands off feet hitting this trail each year is running the landscape a bit ragged.

At its core, geocaching is a terrific way to introduce people (and especially children) to our public lands, which in turn, helps create advocates for conservation — something very much in line with this blog. Hopefully this article didn’t leave other geocachers thinking otherwise. After all, I own several caches myself, and like most cache owners, do my best to ensure they bring people into the wilds while also having minimal impact on the landscape.