It is an unfortunate reality that in the face of Oregon’s population doubling over the past half-century, our trail system has declined. The resulting crowding and overuse is evident on many of the trails that remain, especially on those fringing the rapidly growing Portland region.

This trend is at odds with oft-stated public goals of better public access to nature, re-introducing children to the outdoors, providing more active, quiet recreation near our urban centers, shifting toward a more sustainable forest economy and creating affordable recreation in the interest of social equity.

So, what to do? Build more trails. Soon. And take better care of what we already have.

This article lays out a specific vision for one such trail, an all-season, family-friendly loop in the Columbia Gorge. This would not only be an important step toward meeting those public goals, but also could also become a flagship project for a renewed campaign to expand our trails to meet overwhelming demand.

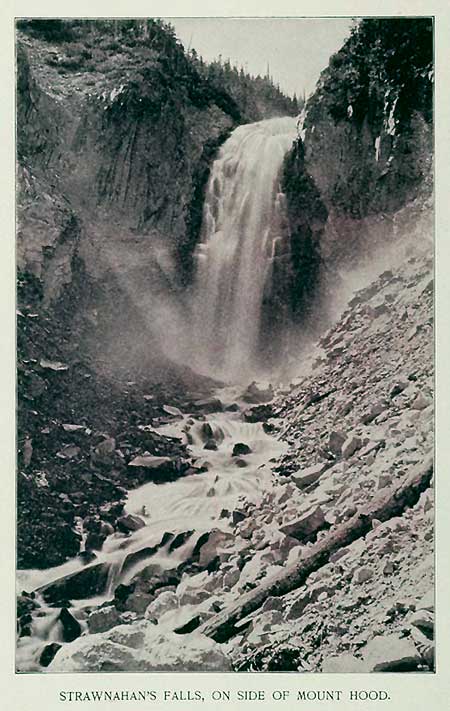

The place is spectacular Bridal Veil Creek, known for its namesake falls, but less known is the string of waterfalls in its shady upper canyon, or the rich history that colors the area.

The Legacy of Bridal Veil

Though deceivingly green and pristine today, the Bridal Veil watershed was once the center of what was arguably the most intensive logging operation in the region.

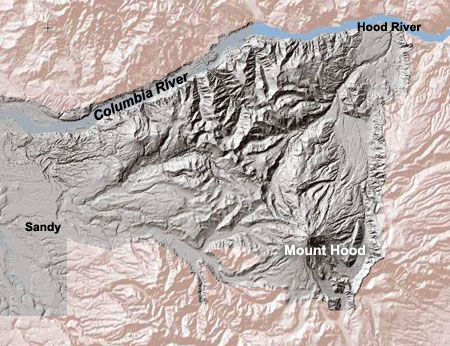

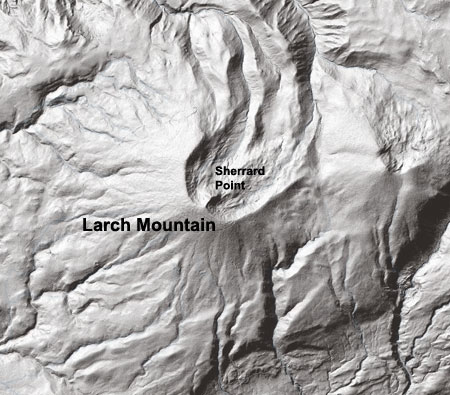

From 1886-1936, the company town of Bridal Veil thrived at the base of Bridal Veil Falls, on the banks of the Columbia River. The mill town at Bridal Veil was connected to a hillside sister mill community known as Palmer, located on the slopes of Larch Mountain. Today’s Palmer Mill Road survives as the connecting route between the two former mills.

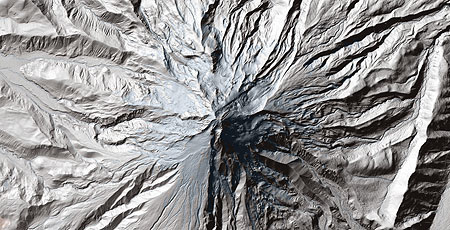

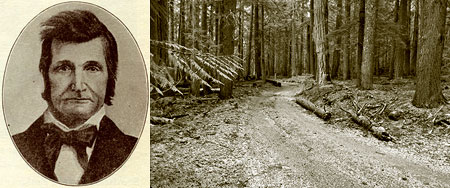

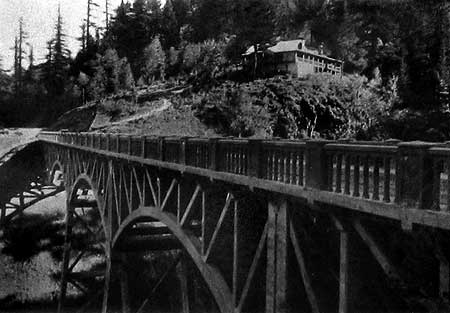

In the turn-of-the-century heyday of these mills, logs were rough-milled at the Palmer site, and sent down a mile-long flume to the Bridal Veil mill for finishing as commercial lumber. The terminus of the flume can be seen in the lower right of the first photo (above), with a huge pile of rough cut lumber piled at its base.

Timber was hauled to the holding ponds at the Palmer site along a series of rail spurs, traces of which can still be found today in the deep forests of Larch Mountain.

The original Palmer site operated until a fire destroyed the mill in 1902, and the New Palmer mill was constructed nearby. New Palmer operated until the Bridal Veil Falls Lumbering Company shut down in 1936, a victim of the Great Depression and the largely logged-out Bridal Veil area.

Kraft Foods bought the mill and surrounding town in 1937, and formed the Bridal Veil Lumber and Box Company. Kraft manufactured its iconic wooden cheese boxes at the mill from 1937-1960, when Bridal Veil was finally shut down for good.

The town site of Bridal Veil had already begun to fade when Kraft bought the community and mill in 1937, and today only the post office and cemetery survive. The tiny post office remains a popular attraction for mailing wedding announcements and invitations (with a “Bridal Veil, OR” postmark), and is now the sole reason for its existence. The cemetery saw its last burial in 1934, and local volunteers now maintain the grounds.

In 1990, the Trust for Public Lands purchased the Bridal Veil site, with the intention of clearing the remaining structures and transferring the land to the U.S. Forest Service for restoration. A decade-long legal battle ensued between local historic preservation interests and the Trust before the buildings were finally cleared, beginning in 2001. The last structure (a church) was demolished in 2011, leaving only the post office.

Though the structures are mostly gone, remnants and artifacts from the Bridal Veil logging era are everywhere in the canyon: moss-covered railroad ties can still be seen on the old logging grades, concrete foundations line the old streets of the town, and chunks of suspension cable and rusted hardware follow the old flume corridor.

Sadly, there is also modern debris in the mix: illegal dumping has plagued Palmer Mill Road for decades, including automobiles that have been rolled over the canyon rim, tumbling into Bridal Veil Creek. At least three recently dumped autos are still lodged above the upper falls today, and several have already been pulled from the creek over the years.

The combination of historic and nuisance debris lining this beautiful canyon present a couple of opportunities for the public. Clearly, the historic traces give a unique glimpse into the past, and an opportunity to interpret the logging history for present-day visitors.

But the nuisance debris also provides an opportunity to engage the public in a major cleanup of the canyon, and ongoing stewardship, in tandem with construction of a new trail.

The Proposal

This proposal for Bridal Veil canyon has two components:

1. Building a 2.5 mile hiking trail to spectacular views of the middle and upper waterfalls along Bridal Veil Creek

2. Converting Palmer Mill Road to become a bicycle trail

The focus of the proposal is on the hiking loop — a new, all-season trail that will offer a premier hike to families and casual hikers, while taking some pressure off crowded routes in the vicinity (such as Angels Rest, Latourell Falls and the Wahkeena-Multnomah trails).

The Palmer Road conversion is a secondary piece that responds to growing demand for new bike trails, as well as the failing state of the road for vehicular traffic (more about that, below).

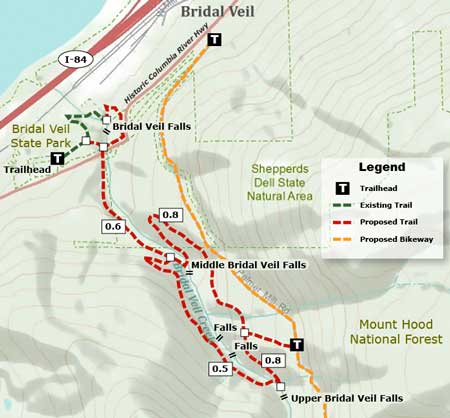

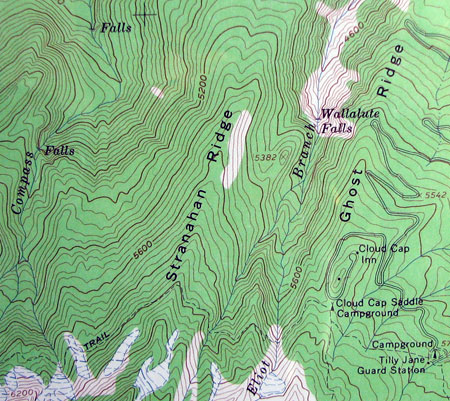

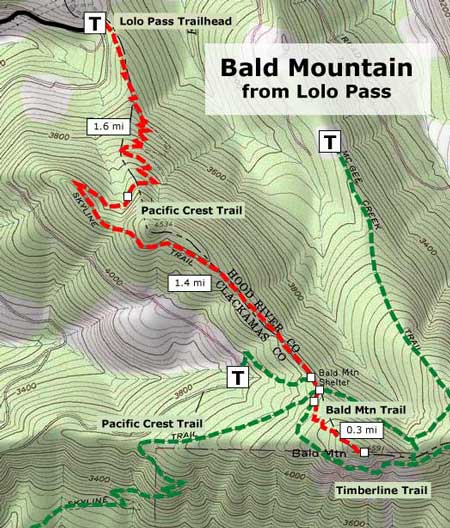

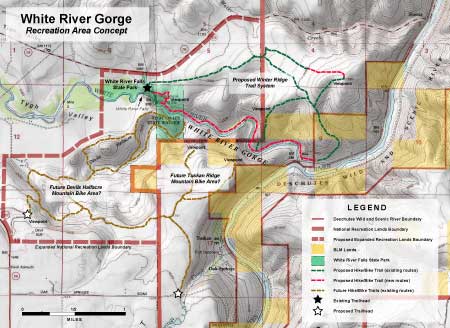

The following trail map shows these proposals in detail:

(click here for a larger version of the map)

One of the unique advantages of building in the Bridal Veil watershed is the already impacted nature of the landscape. Adding a trail here is a modest change compared to a century of road building and logging. The proposal also provides an opportunity to restore some of the environmental damage from past activities in the process, such as illegal dumping and invasive species that have been introduced to the canyon.

Another unique advantage is the opportunity to extend the new trail from the existing trailhead and picnic facilities that exist at Bridal Veil State Park. The park already has a paved parking area, picnic tables, year-round restroom and a couple of short hiking trails. The new trail proposal would build on these amenities, making for a full-service for casual hikers or families with young kids.

The trailhead is also adjacent to rustic Bridal Veil Lodge, and would certainly complement the long-term operating of this historic roadhouse by greatly expanding recreation opportunities in the area.

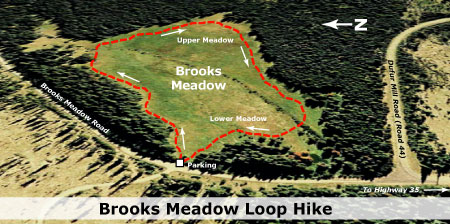

The new trail would begin a few feet beyond the trailhead sign on the existing Bridal Veil Falls trail, turning upstream from the current path. The new route would duck under the Historic Columbia River Highway, and follow the west side of Bridal Veil Creek closely for 0.6 miles to a new footbridge at beautiful Middle Bridal Veil Falls. Here, a few moss-covered remains of the old log flume survive among the ferns and boulders.

The proposed loop forks here, with the stream-level route continuing along the west side of the creek, and the eastern bluff route returning across the proposed bridge (see map, above).

The stream-level route would now climb a switchback to an overlook of Middle Bridal Veil Falls, and continue to traverse the stream for a half-mile, passing two more mid-sized waterfalls. Soon, the trail would arrive at a second bridge, just below magnificent Upper Bridal Veil Falls.

The upper falls is the main attraction of the proposed loop trail — a powerful 100-foot wall of water in a steep amphitheater. Hikers will want to enjoy this spot for a while, perhaps from the proposed footbridge, or possibly from a viewing platform similar to the deck at Bridal Veil Falls.

After taking in the view of the upper falls, hikers would begin the traverse of the east side of the canyon, along the return portion of the proposed loop trail. This section would gently climb the steep canyon walls to a series of open bluffs that frame the gorge. Along the way, a spur trail would connect the loop trail to the proposed bike route along Palmer Mill Road.

The return route would end with a long switchback descent to the proposed footbridge at Middle Bridal Veil Falls, and hikers would retrace their steps for the final 0.6 miles to the trailhead. The new loop would be a total 2.5 miles, round-trip.

The final piece of the puzzle in the trail proposal would be a short return loop on the existing Bridal Veil Falls trail. This route would climb from the existing viewing platform above Bridal Veil Falls, traversing below the scenic highway to a new stream crossing at the highway bridge. Though this route involves extra cost and engineering challenges, it would also create a longer loop that incorporates the existing Bridal Veil Falls trail, for a total of 3.5 miles.

Converting Palmer Mill Road

While the main focus of this proposal is on new hiking trails, the deteriorating state of Palmer Mill Road — and the serious problems it creates in terms of illegal dumping and vandalism — calls the question of whether to allow traffic on this road in the long term?

In 2011, the road was closed for several months to allow for repairs where a sizeable section had failed. Though unintentional, the statement on Multnomah County’s website makes the case for closing the road permanently:

“The isolated road is one of the county’s few remaining gravel roads. The narrow road climbs a steep hillside above Bridal Veil Falls along Bridal Veil Creek.

No homes or businesses are located along Palmer Mill Road. The road was built to serve logging mills in the 1880s that are now long gone. Few cars use the road, so not many people noticed when a landslide closed the route in March 2011, during one of the wettest winters in recent memory.”

At a time when county transportation funds are rapidly dwindling, converting the road to become a bicycle trail would not only help the health of Bridal Veil canyon, it could also remove some of the maintenance burden for the county. It also seems to fit the county’s own direction for the corridor, as the upper segment of Palmer Mill Road has been gated to vehicles for years, and is a favorite route among cyclists and hikers.

Like the proposed Bridal Veil loop trail, a bike trail along Palmer Mill Road already has a developed trailhead. In this case, the paved overflow lot for the Angels Rest trail provides ready-made parking. Therefore, no new accommodations for bike trail users would be needed (though the Angels Rest trailhead is not equipped with an all-season restroom or water).

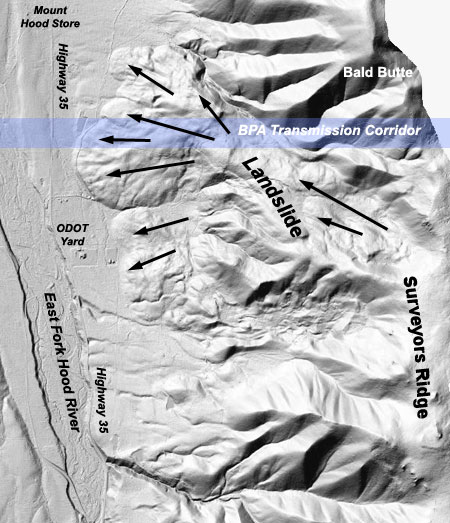

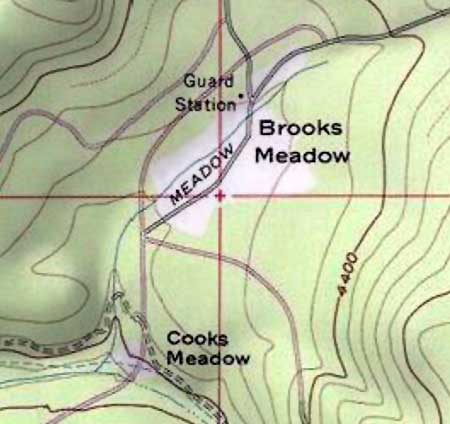

(a caveat to this proposal: the steepness of Palmer Mill Road might limit its suitability for bikes, especially downhill, and therefore might need to be managed accordingly (like the Zigzag Trail near Surveyors Ridge, for example, which requires cyclists to walk bikes in the downhill direction).

What will it take?

This proposal will require a partnership between the U.S. Forest Service (administers the upper portion of the canyon), Oregon State Parks (administers the lower section) and trail advocacy groups. While the proposed loop represents a substantial amount of trail design, engineering and construction, it is well within reach if a public-private partnership can be realized.

The scope of the proposal is about the same as the Wahclella Falls trail, which was rebuilt in the 1990s to include two sizeable footbridges and sections of new tread on steep slopes. However, there would be little or no costs associated with the trailhead at Bridal Veil Canyon, unlike the Wahclella Falls project.

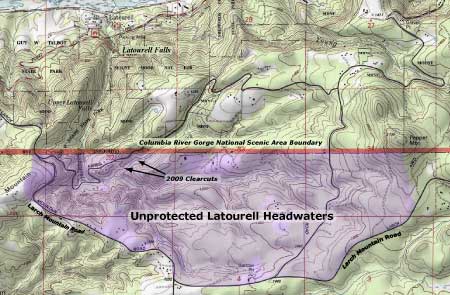

(click here for a larger view of this map)

(click here for a PDF version of this map)

Sound interesting? The best way to advocate for this trail is to simply pass the idea along. I will be advocating the project with Oregon State Parks, eventually, so word-of-mouth support among hikers could be helpful.

To share this concept, download the illustrated PDF version (above) of the map and send it to friends, fellow hikers or even to Oregon State Parks or Forest Service officials, with your own suggestions for how to proceed. That’s how grassroots projects get started, after all!

___________________________

Acknowledgements: this article has been underway for a couple of years, and reflects help from several local Gorge experts. My thanks go to Bryan Swan for his research on the history (and mystery) of Upper Bridal Veil Falls, and to Greg Lief and Don Nelsen for making bushwhack trips with me to Upper and Middle Bridal Veil Falls, respectively. Special thanks go to Zach Forsyth for his intrepid explorations along the less-traveled sections of the canyon, and advice on possible trail alignments.