One of the unexpected discoveries in launching the Mount Hood National Park Campaign in 2004 was the surprising number of people who think our mountain and gorge are already protected as a national park!

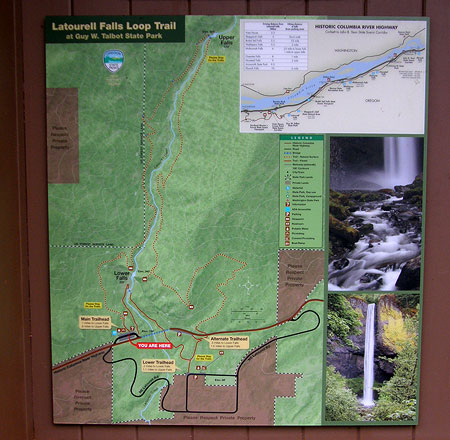

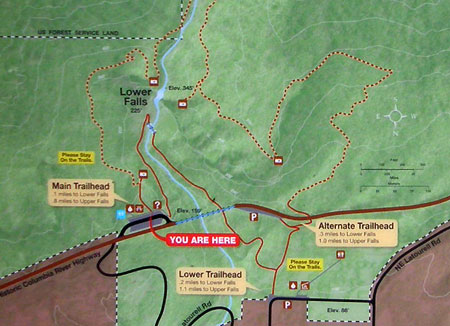

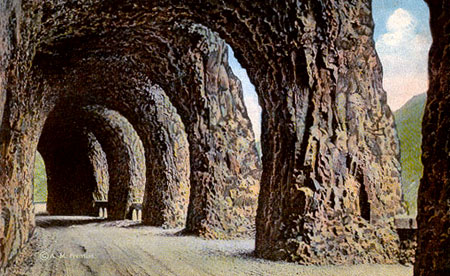

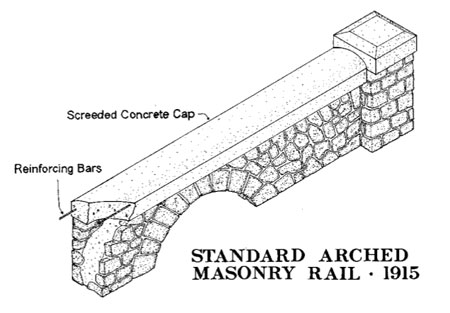

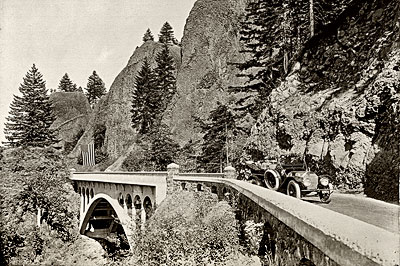

This tragic misconception is shared by newbies and natives, alike, so my conclusion is that it comes from the “park-like” visual cues along the Mount Hood Loop: the historic lodges, rustic stone work and graceful bridges along the old highway. There is also a surprising (if disjointed) collection of interpretive signs that you might expect to find in a bona fide national park.

The interpretive signs around Mount Hood are an eclectic mish-mash of survivors from various public and private efforts over the years to tell the human and natural history of the area.

The oldest signs tell the story of the Barlow Road, the miserable mountain gauntlet that marked the end of the Oregon Trail. The above images show one of the best known of these early signs, a mammoth carved relief that stands at Barlow Pass (the current sign appears to be a reproduction of the original).

Less elaborate signs and monuments of assorted vintage and styles are sprinkled along the old Barlow Road route wherever it comes close to the modern loop highway: Summit Prairie, Pioneer Woman’s Gravel, Laurel Hill.

More recently, the Forest Service and Oregon State Parks have been adding much-needed interpretive signage along the Historic Columbia River Highway (as described in this article), an encouraging new trend.

Thus, I was thrilled when the Forest Service Center for Design and Interpretation in McCall, Idaho contacted me last year about a new series of roadside signs planned for the Mount Hood Loop. They had seen my photos online, and were looking for some very specific locations and subjects.

In the end, the project team picked eight of my images to be included on a series of four interpretive signs. The following is a preview of the signs, and some of the story behind the project. The new signs should be installed soon, and hopefully will survive at least a few seasons on the mountain!

The Signs

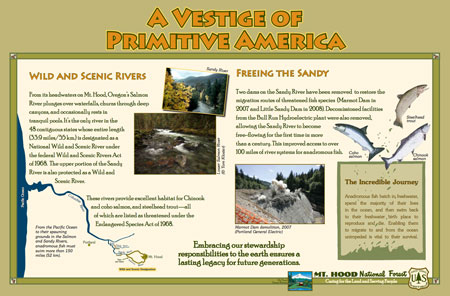

The first installation will be placed somewhere along the Salmon River Road, probably near the Salmon River trailhead. This sign focuses on fisheries and the role of the Sandy River system as an unimpeded spawning stream for salmon and steelhead.

(click here for a large view)

Part of the narrative for this sign focuses on the removal of the Marmot and Little Sandy dams, a nice milestone in connecting the network of Wild and Scenic Rivers in the Sandy watershed to the Columbia. A PGE photo of the Marmot Dam demolition in 2007 is included on the display, along with river scenes of the Sandy and Salmon. The Salmon River image on the first sign is the only one I captured specifically for the project, in early 2012. It’s a rainy winter scene along the Old Salmon River Trail.

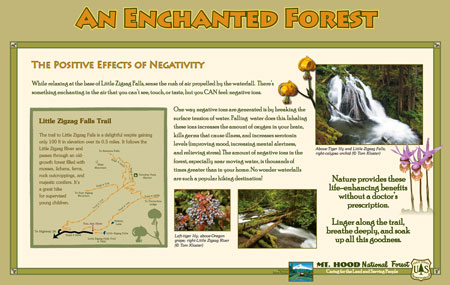

The second sign will be placed at the Little Zigzag trailhead, located along a section of the original Mount Hood Loop highway at the base of the Laurel Hill Grade. The site already has an interpretive sign, so I’m not sure if this is an addition or replacement for the existing (and somewhat weather-worn) installation.

(click here for a large view)

The content of the Little Zigzag sign is unique, launching into a surprisingly scientific explanation of how the negative ions created by streams and waterfalls feed your brain to give you a natural high! Not your everyday interpretive sign..! It also includes a decent trail map describing the hike to Little Zigzag falls, as well as other trails in the area.

The Forest Service used several of my images on this sign: views of Little Zigzag Falls, the Little Zigzag River and several botanical shots are incorporated into the layout.

The Little Zigzag Falls image has a bit of a back story: the Forest Service designers couldn’t take their eyes off a log sticking up from the left tier of the falls. To them, it looked like some sort of flaw in the image. I offered to edit it out, and after much debate, they decided to go ahead and use the “improved” scene. While I was at it, I also clipped off a twig on the right tier of the falls. Both edits can be seen on the large image, below:

(click here for a larger image)

I should note that I rarely edit features out of a photo — and only when the element in question is something ephemeral, anyway: loose branches, logs, or other debris, mostly… and sometimes the occasional hiker (or dog) that walks into a scene!

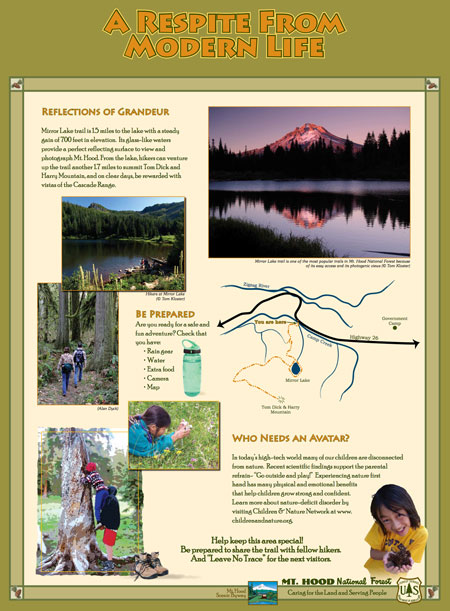

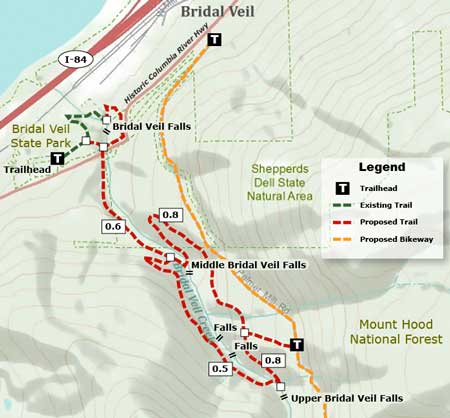

The third sign will be installed at the popular Mirror Lake trailhead, near Government Camp. Like the Little Zigzag sign, this panel has a trail map and hike description for Mirror Lake and Tom Dick and Harry Mountain.

A nice touch on Mirror Lake sign is the shout-out to the Children & Nature Network, a public-private collaborative promoting kids in the outdoors. I can’t think of a better trail for this message, as Mirror Lake has long been a “gateway” trail where countless visitors to Mount Hood have had their first real hiking experience.

(click here for a large view)

The Forest Service team used a couple of my photos in the Mirror Lake layout: a summertime shot of the lake with Tom Dick and Harry Mountain in the background, and a family at the edge of the lake, and a second “classic” view of alpenglow on Mount Hood from the lakeshore.

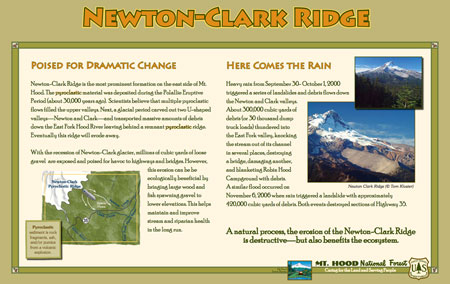

The fourth sign in the series focuses on geology. Surprisingly, it’s not aimed at familiar south side volcanic features like Crater Rock — a theme that was called out in some of the early materials the Forest Service sent me. Instead, this panel describes huge Newton Clark Ridge, and will apparently be installed at the Bennett Pass parking area.

(click here for a large view)

In a previous blog article, I argue Newton Clark Ridge to be a medial moraine, as opposed to currently accepted theory of a pyroclastic flow deposited on top of a glacier. The Forest Service interpretive panel mostly goes with the conventional pyroclastic flow theory, but hedges a bit, describing it as “remnant” of two glaciers… which sounds more like a medial moraine!

The Newton Clark Ridge sign also includes a description of the many debris flows that have rearranged Highway 35 over the past few decades (and will continue to). One missed opportunity is to have included some of the spectacular flood images that ODOT and Forest Service crews captured after the last event, like this 2006 photo of Highway 35 taken just east of Bennett Pass:

The Forest Service used two of my photos for this sign, both taken from viewpoints along the old Bennett Pass Road, about two miles south of the parking area. One wrinkle in how well this sign actually works for visitors is the fact that Newton-Clark Ridge is only partially visible from the Bennett Pass parking lot, whereas it is very prominent from the viewpoints located to the south. Maybe this was the point of using the photos?

There is also a glitch in this panel that I failed to catch during the production phase: the hyphen between “Newton” and “Clark” in the title and throughout the text. There’s a lot of confusion about this point, but it turns out that Newton Clark was one person, not two: a decorated Civil War veteran who fought at Shiloh and Vicksburg, among many prominent battles, then moved to the Hood River Valley in 1887, where he was a local surveyor, farmer and early explorer of Mount Hood’s backcountry.

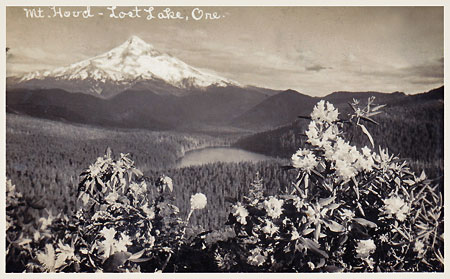

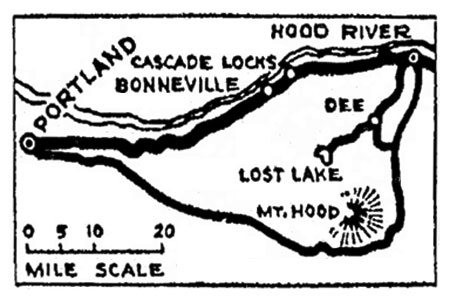

Newton Clark was part of the first white party to visit (and name) Lost Lake, and today’s Newton Clark Glacier and nearby Surveyors Ridge are named for him. The confusion comes from the subsequent naming of the two major streams that flow from the Newton Clark Glacier as “Clark Creek” and “Newton Creek”, suggesting two different namesakes. Hopefully, the local Forest Service staff caught this one before the actual sign was produced!

Strange Bedfellows?

I was somewhat torn as to whether to post this article, as it goes without saying that the WyEast Blog and Mount Hood National Park Campaign are not exactly open love letters to the U.S. Forest Service. So, why did I participate in their interpretive sign project?

First, it wasn’t for the money – there wasn’t any, and I didn’t add a dime to the federal deficit! I don’t sell any of my photos, though I do regularly donate them to friendly causes. So, even though the Forest Service did offer to pay for the images, they weren’t for sale.

One that won’t be built? This sign was originally conceived for Buzzard Point, near Barlow Pass, but it’s not clear if it made the final cut (USFS)

(click here for a large version)

In this case, once I understood the purpose of the project, it quickly moved into the “worthy cause” column, and I offered to donate whatever images the Forest Service could use, provided I see the context — and now you have, too, in this preview of the new signs!

I will also point out that the Forest Service project staff were terrific to work with, and very dedicated to making a positive difference. We’re fortunate to have them in public service, and that’s a genuine comment, despite my critiques of the agency, as a whole.

Here’s a little secret about the crazy-quilt-bureaucracy that is the Forest Service: within the ranks, there are a lot of professionals who are equally frustrated with the agency’s legacy of mismanagement. While I may differ on the ability of the agency to actually be reformed, I do commend their commitment to somehow making it work. I wish them well in their efforts, and when possible, I celebrate their efforts on this blog.

So you want to change the Forest Service from within..?

Given the frustrating peril of good sailors aboard a sinking ship, it turns out there are some great options for supporting those in the Forest Service ranks seeking to make a positive difference. So, I thought I would close this article by profiling a couple of non-profit advocacy organizations with a specific mission of promoting sustainable land management and improving the visitor experience on our public lands. I hope you will take a look at what they do, and consider supporting them if you’re of like mind:

The National Association for Interpretation (NAI) is a not-for-profit 501(c)(3) involved in the interpretation of natural and cultural heritage resources in settings such as national parks, forests, museums, nature centers and historical sites. Their membership includes more than 5,000 volunteers and professionals in over 30 countries.

The Forest Service has a conservation watchdog group all its own, Forest Service Employees for Environmental Ethics (FSEEE), a not-for-profit 501(c)(3) based right here in Oregon. Their mission is to protect our national forests and to reform the U.S. Forest Service by advocating environmental ethics, educating citizens, and defending whistleblowers. The FSEEE membership is made up of thousands of concerned citizens, former and present Forest Service employees, other public land resource managers, and activists working to change the Forest Service’s basic land management philosophy.

I take great comfort in simply knowing that both organizations exist, and are actively keeping an eye on the Forest Service… from within!