Emerald Falls on the proposed Gorton Creek Accessible Trail

The Mount Hood National Park Campaign proposes a major expansion of the trail system in the Columbia Gorge and around Mount Hood, including more opportunities for elderly, disabled and young families to experience nature. After all, hiking is the most basic form of active recreation, and should be available to all of us — especially as our region continues to grow and urbanize.

Proposed Gorton Creek Accessible Trail

Accessible trails are designed to provide access for everyone, and these facilities will be in growing demand as our country continues to age. By 2030, nearly a third of our population will be over the age of 55, and accessible trails will be in demand as never before.

In the spirit of providing accessible trails, this proposed new trail at Gorton Creek would allow for easy access to streamside vistas and photogenic Emerald Falls. This section of trail would bring visitors through a lush forest of Douglas fir, bigleaf maple and red alder.

Autumn on Gorton Creek as viewed from the proposed location of an accessible viewpoint

Gorton Creek becomes increasingly prominent as the trail draws near the stream and the sound of rushing water fills the air. Just below the proposed viewpoint of Emerald Falls and rushing Gorton Creek, there is a large gravel beach at a bend in the stream that could even provide the potential for universal access to the stream, itself — a first in the region.

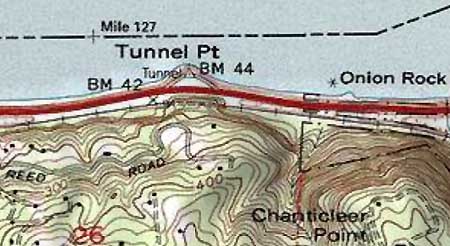

The accessible portion of the new trail would largely follow an existing boot path that, in turn, follows a very old roadbed still shown on USGS maps. Thus, the gentle grade that would meet accessible trail design requirements. The dashed yellow line on the map, below, shows where the roadbed segment could be improved to provide universal access to a streamside overlook just below Emerald Falls.

Proposed Gorton Creek Family Trail

Family trails are designed to allow young children on foot, in backpacks or in strollers to have their first nature experience, and hopefully begin a lifetime of active recreation in nature.

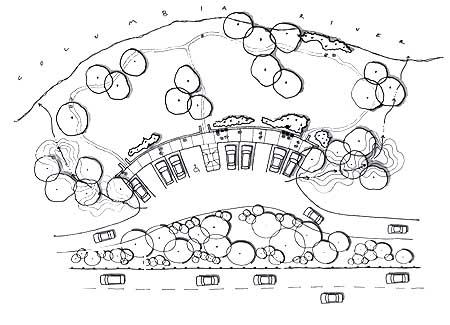

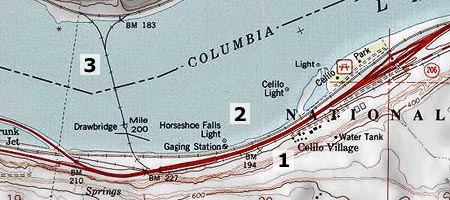

The second part of the proposed Gorton Creek Trail would be designed for young families, with a short, easy grade leading to a viewing platform below Gorton Creek Falls. The falls is a towering 120 foot plunge set against a magnificent wall of columnar basalt, and would provide an exciting destination for budding young hikers. This section of proposed trail is shown in red on the map, above.

The family trail portion of this project would a couple of important objectives. First, it would provide a new hiking option for families with beginning hikers, with easy access from Portland and the potential to camp at Wyeth Campground as part of the adventure. Such trails are in surprisingly short supply in the Gorge, and therefore often crowded when families are most likely to visit, depriving them of a quality nature experience.

Second, this segment of the trail would combine with the lower, accessible segment to allow for extended family outings — grandparents enjoying the lower streamside viewpoint as young children and parents hike the short family spur to the main falls viewpoint, for example, with the extended family camping or picnicking at the Wyeth Campground.

Gorton Creek Restoration

While this proposal would meet growing needs for accessible trails in the region, it would remedy an escalating problem at Gorton Creek: the secret is out on Gorton Creek Falls, and waterfall enthusiasts are wreaking havoc on the trail-less canyon section above Emerald Falls as they scramble to reach the main falls, upstream. The damage to the canyon slopes (see photos, below) and stream bed is particularly worrisome given the important role the stream has as fish habitat.

Gorton Creek Falls is no longer a well-kept secret. Each summer, more visitors are pushing cross-country through the upper canyon, leaving damaged slopes and trampled vegetation in their wake

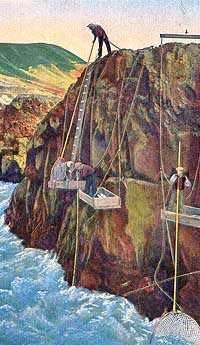

Finally, trail construction could also allow for the washed-out waterworks at Emerald Falls (see photo, below) to be permanently relocated within the trail corridor, and less prone to the periodic failures that plague the current streamside alignment. The water pipeline is currently in a precarious condition, and would greatly benefit from a trail project happening in this canyon sooner than later.

The washed out water supply line for Wyeth Campground hangs from cables anchored to stakes below Emerald Falls

To visit Gorton Creek, drive east of Cascade Locks to the Wyeth exit, turn right, then turn right again on the old highway that parallels I-84. Watch for the Wyeth Campground on the left, just before a bridge over Gorton Creek. If the campground gate is closed, park to the side, and walk through the campground to the well-marked trailhead at the south end — otherwise, you can drive to the trailhead.

To reach Emerald Falls, follow the formal trail 0.1 miles to a junction with Trail No. 400, where it crosses Gorton Creek on an impressive footbridge that kids will want to explore. Continue straight, past the bridge and Trail 400, following the obvious footpath up the east side of the stream canyon for another 0.4 miles. Watch your step around Emerald Falls, as the water works erosion has left abrupt holes and weakened stream banks. Do the canyon a favor, and don’t scramble upstream to Gorton Creek — wait for a trail to be built, instead!

(Editors Note: Trail No. 408 already carries the name “Gorton Creek Trail”, but never comes close to the creek, traversing high above the canyon rim on the shoulder of Nick Eaton Ridge. This trail eventually climbs to the summit of Green Point Mountain — and thus, might be better named the “Green Point Mountain Trail” should a new trail along Gorton Creek become a reality, if not before)