On August 26, 2011, a lightning strike ignited what was to become the Dollar Lake Fire, on Mount Hood’s rugged north side. The fire started in the Coe Branch canyon, just below the Elk Cove trail, and was spotted by numerous hikers.

Initially, it seemed small and manageable. But over the next few days and weeks, arid conditions and strong winds spread the fire from Stranahan Ridge on the east to Cathedral Ridge on the northwest side of the mountain, eventually consuming some 6,300 acres of high elevation forest. The blaze burned through September and into early October, when fall rains finally arrived.

Some of the burn was of the beneficial form, a mosaic fire leaving islands of surviving trees, but much of the fire was too hot and the accumulated forest fuel too plentiful to prevent devastating crown fires from sweeping across the forest. Eventually, the fire destroyed most of the standing timber and burned the forest duff down to mineral soil throughout most of the burn area.

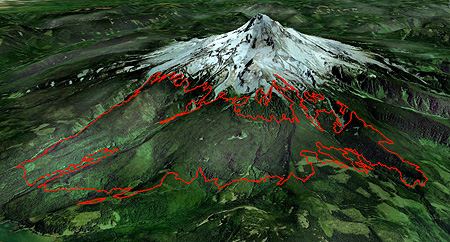

The fire was contained entirely within the Mount Hood Wilderness, thanks to the recent Clear Branch additions that expanded the wilderness boundary on the north to encompass the Clear Branch valley and the high country surrounding Owl Point, to the north. While this complicated fire fighting, it has also created a living laboratory for forest recovery, as the USFS is unlikely to assist the reforestation process inside the wilderness boundary. The Forest Service map, below, shows the broad extent of the fire.

Though the fire burned to the tree line in several spots, a surprising amount of terrain along the iconic Timberline Trail was somehow spared. While the burn touched Elk Cove and Cairn Basin, WyEast Basin and Barrett Spur are well beyond the burned area. The Clear Branch wilderness additions to the north were mostly spared, as well.

The New Vista Ridge: After the Fire

The following is a photo essay from my first visit to the burn, on June 22, 2012, and is the first in what will eventually be a series of articles on the aftermath of the fire.

The devastation left by the fire is awesome to witness, but also starkly beautiful when you consider the context of a forest fire. After all, this event is part of the natural rhythm of the forest just as much as the changing of seasons.

From this point forward, we will have a front-row seat to the miracle of life returning to the fire zone, much as we’ve watched life return to the Mount St. Helens blast zone over the past 32 years. And as my photos show, the rebirth of the forest ecosystem has already begun on Mount Hood’s northern slopes.

From the Vista Ridge trailhead, I followed the Vista Ridge Trail to the snow line, above about 5,000 feet. The Vista Ridge trailhead is completely untouched, though the fire swept through a vast area immediately to the south. Yet, no sign of the fire is evident at the trailhead marker (above).

A bit further up the trail, at the Old Vista Ridge trailhead, the fire zone comes into view. Where green forests existed last summer, browned foliage and a burned forest floor spread out east of the junction. This fringe of the fire is of the healthy “mosaic” form, sparing large trees, while clearing accumulated forest debris.

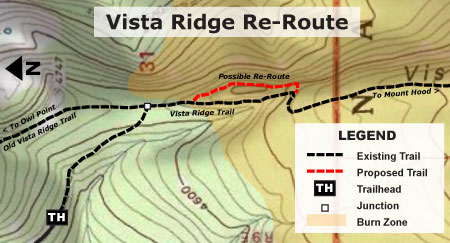

An unexpected benefit of the fire came last fall, when the USFS added the long-neglected Old Vista Ridge trail to official agency fire maps (below) released to the public. Volunteers began restoring this beautiful trail in 2007, but formal acknowledgement of the route on USFS maps is a welcome development.

Clearly, the restoration of the Old Vista Ridge trail helped fire fighters reach this area, and could have served as a fire line had the blaze swept north, across the Clear Branch. Hopefully this is an indication that the Old Vista Ridge trail will someday reappear on the USFS maintenance schedule, too.

Turning south on the Vista Ridge trail from the Old Vista Ridge junction, the wilderness registration box and map board seem to have received divine intervention from the fire — the blaze burned within a few feet of the signs, yet spared both. From here, the Vista Ridge trail abruptly leaves the scorched fringe of the fire, and heads into the most devastated areas.

From about the 4,700 foot level, the Dollar Lake Fire burned the forests along Vista Ridge to bare earth. In this area, the entire forest crowned, leaving only a scattering of surviving trees where protected by topography or sheer luck. Forest understory, woody debris and duff burned to mineral soil, leaving a slick, muddy surface of ash. For those who have hiked through the previous Bluegrass Fire or Gnarl Fire zones on the east slopes of Mount Hood, this eerie scene is familiar.

Amid the devastation in this hottest part of the Dollar Lake Fire, signs of life are already emerging. At this elevation, one of the toughest survivors is beargrass, a member of the lily family with a deep rhizome that allows plants to survive even the hottest fires. These plants are normally evergreen, but were completely scorched in the fire. The new grown in this photo (below) has emerged this spring.

Another surprise is avalanche lily, one of the more delicate flowers in the subalpine ecosystem. Like beargrass, these plants survive thanks to a bulb located deep enough in the soil to escape the heat of the fire. As one of the early bloomers in the mountain forests, these plants area already forming bright green carpets in the sea of fire devastation (below).

Another of the beneficial aspects of the fire comes into view a bit further up the trail: several sections of Vista Ridge had long been overgrown with thickets of overcrowded, stressed trees that were ripe for a burn.

Over the coming years, these areas are likely to evolve into beargrass and huckleberry meadows like those found at nearby Owl Point or along Zigzag Mountain, where fires have opened the landscape to sun-loving, early succession plants.

One human artifact was uncovered by firefighters — a coil of what must be telephone cable (below). This is a first along the Vista Ridge trail, but makes sense given the insulators and cable found along the Old Vista Ridge trail.

It’s hard to know what this connected to, but on the north end, it served the old Perry Lake Guard Station and lookout, just east of Owl Point. It’s possible this line extended to the Bald Mountain lookout, though I have been unable to verify this on historic forest maps.

Though much of the devastation zone still consists of blackened trees and soil, some of the burned forest has begun to evolve into the uniquely attractive second phase. This happens when scorched bark peels away from trees to reveal the often beautiful, unburned wood beneath.

Soon, all of the trees in this forest will shed their bark. The skeletons of thousands of trees will emerge in colors of red, yellow and tan, then gradually fade to a bleached gray and white with time.

The burned trees of Vista Ridge are just beginning to shed their blackened bark, revealing beautiful trunks unscarred by the fire.

This second phase of the fire is helped along by winter snow. As the scene above shows, the freeze-thaw and compacting effects of the snow pack have already stripped many trees of their bark beneath the now-melted snowpack. Hot summer sun will continue this process, shrinking the remaining bark until it drops from the drying tree trunk.

This process of de-barking is the first in a post-fire sequence of events that will recycle much-needed organic matter to the forest floor. Twigs and tree limbs will soon fall, and over time, whole trees will begin to drop. This is a critical phase in stabilizing the forest soil, when low vegetation is still just beginning to re-establish in the fire zone.

The next few images show the extent of the Dollar Lake Fire, as viewed from Vista Ridge. To the east (below), The Pinnacle was mostly burned, but the fire somehow missed stand of trees just below the north summit.

These trees will play an important role in reforestation of the area, partly because so few trees survived the fire, but also because of their geographic location above the surrounding forest, where wind will widely scatter their seeds.

To the south, the area above Elk Cove known as 99 Ridge (shown below) was partly spared, though the fire did scorch the east slopes of the ridge. From this side (to the west), the Timberline Trail corridor was almost completely spared. Ironically, Dollar Lake — the namesake for the fire — appears to have been spared, as well.

To the west of 99 Ridge, WyEast Basin was also spared, but the area along the Timberline Trail to the west of the basin, along the upper sections of Vista Ridge, was largely burned.

This panoramic view (below) encompasses the entire mid-section of the fire, from Stranahan Ridge on the horizon to Vista Ridge, on the right. This is a new viewpoint along a largely unnoticed rocky scarp on the east shoulder of Vista Ridge, now revealed thanks to the fire.

(Click here for a much larger panoramic view]

A Changed Landscape

Those who have explored Mount Hood’s north slopes over the years will surely mourn the loss of the beautiful forests of noble fir and mountain hemlock that once stood here — I certainly have. But this is also a chance to watch the ecosystem recover and restore itself over time, as it has for centuries. Among the surprising benefits are the new scenic vistas that are suddenly available, giving a bit more meaning to the name “Vista Ridge.”

By following the true ridge top of Vista Ridge, the new views extend east across Laurance Lake and the Clear Branch valley to Bald Butte and the Columbia Basin (above). Most of the area below the ridge is not burned, and this new perspective on the recent additions to the Mount Hood Wilderness is both unexpected and beautiful.

To the north, the new views include the rugged and little-known Owl Point area of the expanded Mount Hood Wilderness (reached by the Old Vista Ridge trail). Mount Adams rises in the distance, above the talus fields and meadows of Owl Point.

This suddenly very scenic “true” ridge along the lower portion of Vista Ridge is easy enough to hike by simply following the ridge top where the existing trail heads into a narrow draw, about one-half mile from the Old Vista Ridge trail junction. It’s worth the visit if you’d like to inspect the scenery and Dollar Lake Fire up-close.

But in the spirit of recasting the Vista Ridge trail in the aftermath of the fire, and taking in these new views, now would be the perfect time to simply realign the trail along the ridge top. As shown on the map (below), this project could be done in a weekend by volunteers, if approved by the Forest Service.

(Click here for a larger map]

The fire has already done the heavy work of trail building by clearing the ground to mineral soil: designing and completing a realigned trail here would be quite straightforward. The slope of the ridge top, itself, is surprisingly gentle and would allow for an easy grade, similar to the current trail.

I hope to pitch this idea to the Forest Service, so if you’re interested in getting involved, watch the Portland Hikers forum for updates. That’s where volunteer work parties will be organized if there is interest from the USFS.

Until then, take the time to explore the fire zone, and watch the unfolding forest recovery firsthand. Visit the Portland Hikers Field Guide for directions to the Vista Ridge Trailhead.