Officially, Mount Hood has twelve glaciers, though two — the Langille on the north side and Palmer on the south side — seem to have slowed to permanent snowfield status. The distinction comes from downward movement, which typically results in cracks, or crevasses, in the moving ice. Crevasses are the telltale sign of a living glacier.

Living glaciers are conveyor belts for mountain ice, capturing and compacting snowfall into ice at the top of the glacier, which then begins to flow downhill from the sheer weight of the accumulation. This downward movement becomes river of ice that carries immense amounts of rock and debris captured in the ice, eventually carving U-shaped valleys in the mountain.

Mount Hood’s largest glaciers carved the huge canyons we see radiating in all directions from the mountain today. These canyons were made when the glaciers were much larger, during the Pleistocene ice age that ended several thousand years ago. The ice on Mount Hood has since retreated, though today’s much smaller glaciers continue their excavating high on the mountain.

The smallest glaciers on Mount Hood are the Coalman Glacier, located high in the volcano’s crater, and the Glisan Glacier, located on the northwest shoulder of the mountain. They are tiny compared to the impressive Eliot, Ladd, Coe and Sandy glaciers, but these tiny glaciers are still moving, have well-developed crevasses and both are clearly separate from the larger glaciers. Thus, they were recognized as living glaciers in their own right when Mount Hood was being mapped more than a century ago.

Another tiny glacier is without a formal name, and would have been Mount Hood’s thirteenth glacier had it been mapped with the others in the early 1900s. Known informally as the Little Sandy Glacier, this small body of ice is perched on the rocky shoulder of Cathedral Ridge, near the Glisan Glacier. The Little Sandy hangs on cliffs high above the sprawling Sandy Glacier, which it drains into.

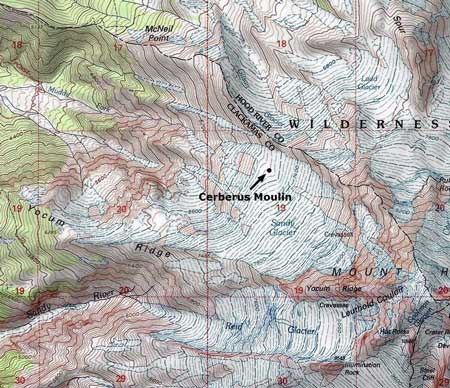

The map below shows each of Mount Hood’s glaciers, from the tiny Glisan to the massive Eliot, largest on the mountain:

[click here for a larger version of the map]

This article takes a closer look at these lesser-known, tiny glaciers. While small, all three have been surprisingly resilient in the era of climate change, when our glaciers are rapidly shrinking. Their tiny size and survival (so far) makes them helpful indicators of the long-term effects of global warming on Mount Hood, and a visual reminder of just how fragile our alpine ecosystems are as the planet continues to heat up.

The Coalman Glacier

This glacier is known to few, and yet is probably the most visited on Mount Hood. The Coalman Glacier fills the crater of Mount Hood, extending from below the summit to Crater Rock, and is crossed by thousands of climbers following the popular south side route to the summit each year. Along their climb, they follow a ridge of ice along the glacier called “The Hogsback” to the Coalman Glacier’s “bergschrund”, the name given to a crevasse that typically forms near the top of most glaciers, and a common feature to many glaciers on Mount Hood. For climbers on Mount Hood, the bergschrund on the Coalman Glacier is simply called “The Bergschrund”, and it is the main technical obstacle on the south side route to the summit.

The entire Coalman Glacier lies above 10,000 feet, and as a result, this tiny glacier is well-situated to survive a warming climate. Historic photos (shown later in this article) suggest the Coalman Glacier was once connected to the White River Glacier, located immediately below, as recently as the late 1800s.

The Coalman Glacier was named for Elijah “Lige” Coalman, the legendary mountain guide who manned the former fire lookout on the summit of Mount Hood from 1915 to 1933. Lige Coalman climbed Mount Hood nearly 600 times in his lifetime, sometimes making multiple climbs in one day to carry 100 pound loads of supplies to the summit lookout. In Jack Grauer’s classic Mount Hood: A Complete History, he describes Lige Coalman’s legendary stamina:

“…The great vitality of Coleman was demonstrated by one day he spent in 1910. He and a climbing client ate breakfast at the hotel in Government Camp. They then climbed to the summit of Mount Hood and down to Cloud Cap Inn where the client wanted to go. After lunch at Cloud Cap, Lige climbed back over the summit and arrived for dinner at Government Camp at 5:00 p.m.”

The Coalman Glacier was formally recognized as a separate body of ice from the nearby White River and Zigzag glaciers in the 1930s. However, this tiny glacier went unnamed until Lige Coalman died in 1970, and the Oregon Geographic Names Board named the small glacier he had navigated hundreds of times in his memory. Fittingly, Lige Coalman’s ashes were spread on Mount Hood’s summit.

Though the south side route is considered the easiest way to the summit of Mount Hood, every route on the mountain is dangerous. Many tragedies have unfolded over the decades on the Coalman Glacier, when climbers have fallen into The Bergschrund crevasse or slid into the steaming volcanic vents in the crater. Perhaps most notorious was the May 2002 climbing disaster, when three climbers were killed and four injured by a disastrous fall into The Bergschrund.

While the 2002 accident was tragic enough, it was the rescue operation that made the incident infamous when an Air Force helicopter suddenly crashed onto the Coalman Glacier, rolling several times before coming to a rest below the Hogsback. News cameras hovering above the scene broadcast the event in real-time, and the sensational footage was seen around the world. Though several Air Force crew were injured, nobody was killed in the helicopter crash.

The Glisan Glacier

The Glisan is Mount Hood’s smallest named glacier, tucked against Cathedral Ridge on the northwest side of the mountain. This tiny glacier is hidden in plain sight, located directly above popular Cairn Basin and McNeil Point, where thousands of hikers pass by on the Timberline Trail every year. It was named for Rodney Lawrence Glisan Jr. by the Oregon Geographic Names Board in 1938. The name was proposed by the Mazamas, Mount Hood’s iconic climbing club, following an expedition to the northwest side of the mountain in 1937.

Glisan was a prominent Portland lawyer and civic leader in the late 1800s and early 1900s, and son of one of the founding fathers of the city. He served on the Portland City Council and in the Oregon Legislature, as well as other civic roles. But his passion was for the outdoors, and as a Mazama, Rodney Glisan climbed most of the major Cascade and Sierra peaks during his eventful life.

The glacier that carries Rodney Glisan’s name was once much larger, and its outflow carved a steep canyon lined with vertical cliffs that now form the shoulder of the lower ramparts of Cathedral Ridge. Today, this rugged canyon is without trails and unknown to most who visit the mountain.

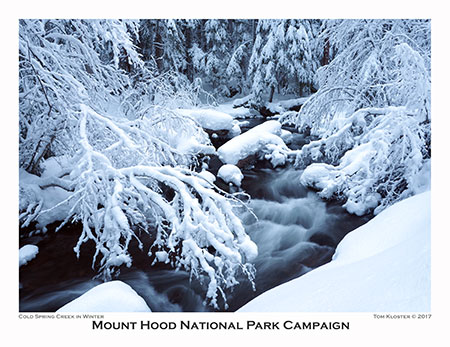

Most hikers visiting McNeil Ridge wouldn’t know they’re looking at the Glisan Glacier as they make the final climb above the tree line, but the glacier’s outflow is a popular stop along the way. This beautiful stream flows through some of the finest wildflower meadows on the mountain (pictured above).

Oddly enough, this glacial stream is unnamed, though it’s much larger than many named streams on the mountain. In fact, it’s the only glacial outflow on the mountain that is unnamed. Thus, on my growing list of planned submissions to the Oregon Geographic Names Board is to simply name this pretty stream “Glisan Creek”, since it’s a prominent and helpful landmark along the Timberline Trail. Naming the creek might bring a bit more awareness and appreciation for the tiny Glisan Glacier, too!

As Mount Hood’s glaciers go, the Glisan isn’t much to look at today. The glacier is much smaller than when it was named in the 1930s, judging by topographic maps (below) that show a lower portion of the glacier that has since become a series of permanent snowfields that are no longer part of the glacier.

The Glisan Glacier also has an odd shape, wider than it is long. Presumably, this is due to both shrinking over the past century and possibly winter wind patterns affecting snow accumulation on this little body of ice. But it is moving, with a prominent series of crevasses opening up every summer on its crest. It’s also surprisingly resilient in its modern, shortened state, bucking the trend (for now) of shrinking glaciers throughout the Cascades.

Topographic maps still show the former extent of the Glisan Glacier in the mid-1900s, when it extended to nearly 6,000 feet in elevation. Today, the glacier has retreated to about the 7,000-foot level.

The position of the Glisan Glacier on northwest side of the mountain could also be part of the explanation for its resilience. The glacier flows from the north side of Cathedral Ridge, where it is protected from the hottest late summer sun, and it also benefits from being in the direct path of winter storms that slam the west face of the mountain with heavy snowfall. Will the Glisan Glacier continue to survive? Possibly, thanks to its protected position and having already retreated to the 7,000-foot elevation. Time will tell.

The Little Sandy Glacier

This little glacier should have been Mount Hood’s thirteenth named glacier, but it has the misfortune of lying very close to the much larger Sandy Glacier and was passed over when the first topographic maps were created in the early 1900s. And yet, it was called out in Forest Conditions in the Cascade Range, the seminal 1902 original survey of the (then) “Cascade Forest Reserve”, the precursor to the national forests that now stretch the length of the Oregon Cascades:

It was tiny then, at just 80 acres. But at the time of the 1902 survey, the Reid, Langille, Palmer and Coalman glaciers had yet to be named, so this will be my argument in adding the Little Sandy Glacier to my (still!) growing list of name proposals for the Oregon Board of Geographic Names to consider.

Why is a name important for this tiny glacier? In part, because without names we tend to not pay attention to important features on our public lands, usually to their detriment. But in the case of the Little Sandy Glacier, there are some good public safety arguments, since the glacier is adjacent to a couple of the climbing routes used on the mountain. Formalizing its name could help search and rescue efforts compared to the informal use of the name today.

Like the nearby Glisan Glacier, the Little Sandy is oddly shaped. Wider than it is long, it hangs seemingly precariously on a massive cliff and is heavily fractured with crevasses. In summer, meltwater from the Little Sandy cascades over long cliff and down a talus slope where it then flows under the Sandy Glacier, joining other meltwater streams there.

What does the future hold for the Little Sandy Glacier? Like the Glisan Glacier, it benefits from heavy snow accumulation where winter storms pound the west face of the mountain. Yet, unlike the Glisan, the Little Sandy Glacier hangs on a southwest-facing wall and is exposed to direct afternoon sun in summer.

Surprisngly, this doesn’t seem to have dramatically affected the size of the glacier over the years, perhaps because it sits so high on the mountain. The base of the glacier is at an elevation of about 8,400 feet (higher than Mt. St. Helens) and the upper extent of the glacier begins just above 9,000 feet. This combination of high elevation and heavy winter snowpack suggest the Little Sandy Glacier will continue to survive for some time to come, even as global warming continues to shrink Mount Hood’s glaciers.

Tracking Mount Hood’s Changing Glaciers

Who is tracking the changes in Mount Hood’s glaciers? The answer is a collection of federal and state agencies, university researchers and non-profits concerned with the rapid changes unfolding on the mountain.

The U.S. Geological Survey has the most comprehensive monitoring program for Mount Hood, though it is mainly focused on volcanic hazards presented by the mountain. From this perspective, the glaciers and permanent snowfields on Mount Hood represent a disaster risk in the event of renewed volcanic activity, as past eruptions have triggered massive mudflows when snow and ice were abruptly melted by steam and hot ash.

The late 1700s eruptions that created today’s Crater Rock and the smooth south side that Timberline Lodge sits on also sent mudflows down the Sandy River to its confluence with the Columbia River. The delta of mud and volcanic ash at the confluence gave the river its name, when the Lewis and Clark Expedition reached the scene just a few years after the event, calling it the “quick sand river”. The potential reach of future mudflows is why the USGS continues to monitor Mount Hood’s glaciers.

The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and other water resource and fisheries agencies are also tracking the glaciers from the perspective of downstream water supplies and quality. Mount Hood’s glaciers not only provide critical irrigation and drinking water for those who live and farm around the mountain, they also ensure cool water temperatures in summer that are critical for endangered salmon and steelhead survival.

In academia, Portland State University geologist Andrew Fountain has been a leading local voice in tracking change in our glaciers, collaborating with federal agencies to monitor glaciers across the American West. Several PSU students have completed graduate theses on Mount Hood’s glaciers under Dr. Fountain, including glaciologist Keith Jackson’s excellent research on the Eliot Glacier.

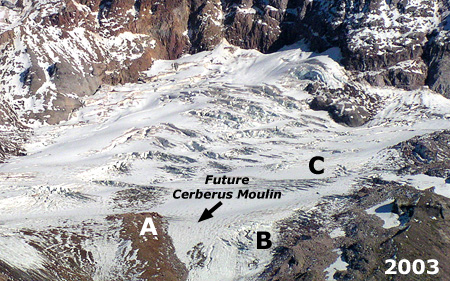

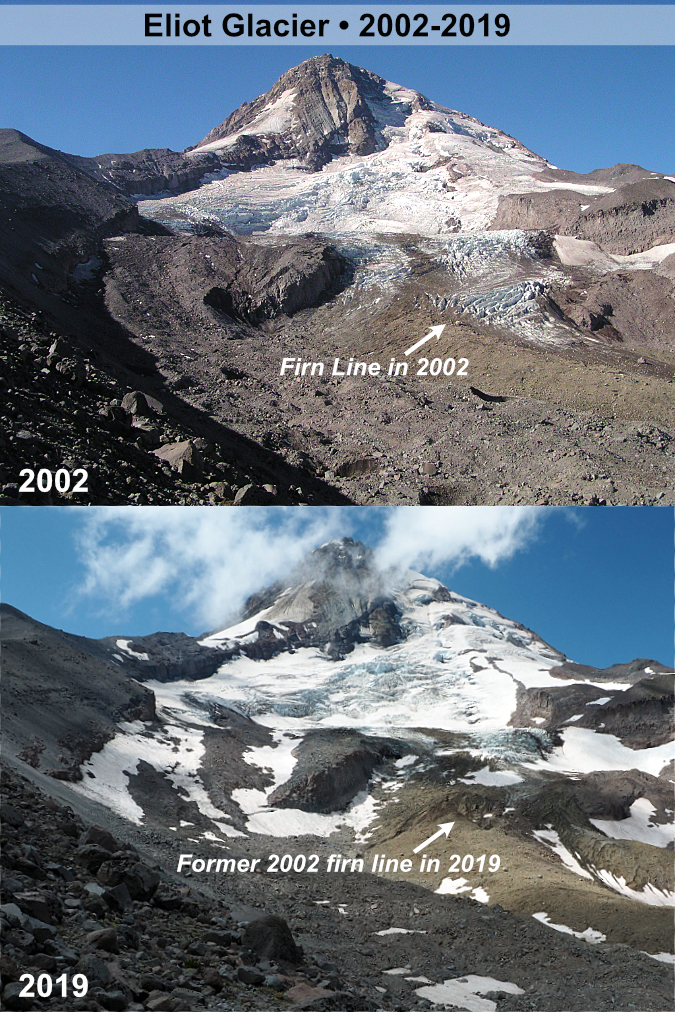

Dr. Fountain’s research features photo pairing where historic images of Mount Hood’s glaciers have been recreated to show a century of change on the mountain. These images (above and at the top of the article) of the White River and Eliot glaciers are examples, and show the power of these comparisons in understanding the scale and pace of change.

The following is a shorter-term comparison of my own images of the Eliot Glacier, taken in 2002 and 2019 at about the same time of year (in late summer). Look closely, and the changes are profound even in this 17-year timeframe. Geologists call the boundary on a glacier where melting exceeds accumulation the “firn line”. Typically, glaciers appear as mostly ice and snow above the firn line compared to much more rock and glacial till below the firn line, where the ice is melting away and leaving debris behind.

In 2002, the firn line on the Eliot Glacier had risen the lower icefall as the glacier receded, as shown in the image pair, above. The 2002 firn line is indicated by the white and blue ice still dominating the lower icefall. But by 2019, the firn line had moved partway up the lower icefall, as shown in the second image. Over time, scientists expect the glaciers on Mount continue to gradually retreat in this way as they increasingly losing more ice than they gain each year in our warming climate.

What Lies Ahead?

Will Mount Hood’s glaciers completely disappear? Perhaps, someday, if global warming goes unchecked. If climate change can be slowed, we may see the glaciers stabilize as smaller versions of what we see today. While the few remaining glaciers in the Rockies are already very small and on the brink of disappearing, glaciers on the big volcanoes of the Cascades of Oregon and Washington are still large and active. They have advantage of a very wet and cool winter climate that ensures heavy snowfall at the highest elevations, even as the climate warms.

One way to preview the future of Mount Hood’s glaciers is to look south to California’s Mount Shasta, at the lower end of the Cascade Range. At just over 14,000 feet, Shasta is tall enough to have seven named glaciers, even in a much warmer climate — though only four seem to still be active. Compare that to Mount Rainier, in Washington, which is also a 14,000-foot volcano, but has 26 glaciers, with several very large, active glaciers that dwarf anything found on Mount Shasta or Mount Hood.

The difference is latitude, of course. Climate change is having the effect if sliding us gradually toward the warmer climate we see to the south today, at Mount Shasta, where glaciers are smaller, but still survive above the 10,000-foot level. If Shasta is an indicator, then glaciers will continue to flow for some time at the upper elevations of Mount Hood and the other big volcanoes in northern Oregon and Washington for some time to come, perhaps even surviving if climate change remains unchecked.

In the meantime, the changes on Mount Hood are just one more reminder of how climate change is impacting almost every aspect of our lives and our natural legacy, and why changing the human behavior that is driving climate change is the existential challenge of our time. Though time is short, we can still ensure that future generations will see spectacular glaciers flowing down Mount Hood’s slopes in the next century.