Sometime last winter a picturesque bigleaf maple framing Wahclella Falls tumbled into Tanner Creek, likely under the stress of heavy snow or ice. In any other spot, this event might have gone unnoticed, but the Wahclella maple had the distinction of a front row seat at one of the most visited and photographed waterfalls in the Columbia River Gorge.

“Change is the only constant. Hanging on is the only sin.”

-Denise McCluggage

Tanner Creek gorge is no stranger to change. In the spring of 1973, a massive collapse of the west wall, just below Wahclella Falls, sent a huge landslide into the creek, temporarily forming a 30-foot deep lake behind the jumble of house-size boulders. Today, the popular Wahclella Falls trail crosses the landslide, providing a close-up view of the natural forces that have created this magnificent place.

By contrast, the demise of the Wahclella maple is a very small change, indeed. But a closer look provides a glimpse into some of the more subtle changes that are part of the perpetually unfolding evolution this beautiful landscape. The following are nearly identical photos captured six years apart, in 2006 and 2012, and the changes over that short span are surprising:

[Click here for a larger view]

Comparing these images, one obvious change is in the stream, itself where (1) an enormous log has been pushed downstream by the force of Tanner Creek, testament to the power of high water. In the center of the scene (2) a young bigleaf maple has doubled in height, obscuring the huge boulder that once sheltered the tree, and on course to obscure the footbridge, as well. New growth is also filling in (3) along the new section of raised trail built on gabions in the 1990s (gabions are wire mesh baskets filled with rock, and were used to build up the trail along the edge of Tanner Creek)

The main change to this scene is the Wahclella maple (4), itself. Because the tree fell into a brushy riparian thicket, the fallen trunk and limbs have already been largely overtaken by lush spring growth of the understory. In a few short years, the fallen tree will disappear under a thick layer of moss and ferns, completing the forest cycle.

[Click here for a larger view]

But the story of the fallen Wahclella maple doesn’t end there, thanks to the unique adaptive abilities of bigleaf maple. Unlike most of our large tree species, bigleaf maple is prolific in sprouting new stems from stumps or upturned root balls. The massive, multi-trunked giants that appear in our forests are the result of this form of regeneration.

[Click here for a larger view]

In this way, the Wahclella maple already seems to be making a comeback. With its former trunk still lying nearby, the shattered base of the tree has sprouted several new shoots this spring. In time, there’s a good chance that some of these shoots will grow to form a new, multi-trunked tree, perhaps one that is even more magnificent for future generations of photographers.

In the meantime, the old maple tree is a reminder that the beauty of the area is forever a work in progress, and how fortunate we are to watch the each stroke of nature unfold.

“The best thing about the future is that it comes only one day at a time.”

-Dean Acheson

_______________________________

How to visit Wahclella Falls

Though hardly a secret anymore , the hike to Wahclella Falls remains a less traveled alternative to other short waterfall hikes in the Gorge. The trail is generally open year-round, though the best times for photography are in May/June, when spring greenery is at its peak, and in late October, when the bigleaf maples light up the forest with bright yellow and orange hues.

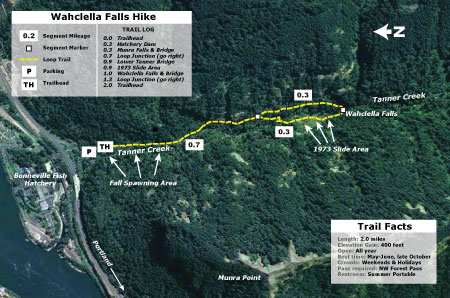

[Click here for a larger, printable version of this map]

This is a terrific family trail, thanks to several dramatic footbridges, two waterfalls, a staircase, caves (!) and several streamside spots safe for wading or skipping stones. Young kids should be kept close, however, since there are also some steep drop offs along sections of the trail. For kids, midweek in midsummer is a perfect time to visit.

Another fascinating time to visit with kids is during the fall spawning season, when the stream below the hatchery diversion dam is filled with returning salmon and steelhead within easy view of the trail.

The trailhead for Wahclella Falls is easy to find. Follow I-84 east from Portland to Bonneville Dam (Exit 40), turning right at the first stop sign then immediately right into the trailhead parking area along Tanner Creek, where a Northwest Forest Pass is required. Portable toilets are provided at the trailhead from spring through early fall.

The trail begins at a gate at the south end of the parking area, and initially follows a rustic gavel road to a small diversion dam that provides water for the Bonneville Fish Hatchery. From here, the route crosses a footbridge in front of Munra Falls, and becomes a proper hiking path. Head right (downhill) at a fork in the trail 0.7 miles from the trailhead to begin the loop through the towering amphitheater surrounding Wahclella Falls, then retrace your steps 0.7 miles to the trailhead after completing the 0.6 mile loop portion of the trail. Enjoy!