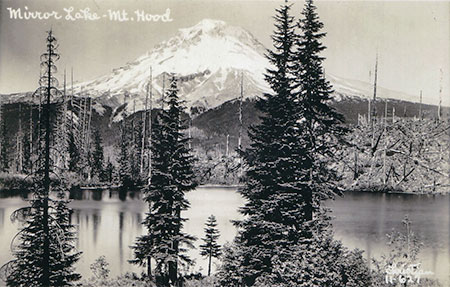

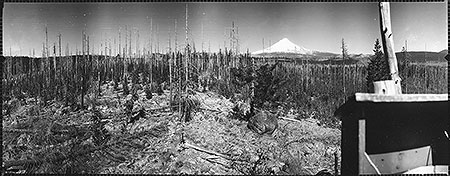

Scorched Mirror Lake just beginning to recover from the Sherar Burn in early 1900s

Oh, if only our lives spanned 800 years instead of 80! No doubt we would see (and zealously protect) our world differently with the benefit of that long perspective. And it turns out that Bowhead whales, Greenland sharks and even pond Koi can live well beyond two centuries. Heck, the lowly Icelandic clam can live up to 500 years! The advantage these creatures have over humanity is the ability to see the cycles of life as a perpetual rhythm, not simply discrete events.

Which brings us to the deep sadness that so many of us are experiencing with Eagle Creek Fire of 2017 in the Columbia River Gorge. To so many of us, losing the lush green forests that framed the waterfalls and cliff-top vistas in the Gorge is like losing an old friend.

Yet, with a bit more longevity, we’d be able to see the cycles of fire and recovery repeat in succession, and we could even look forward to walking again among 200 year old forest giants along today’s scorched trails in the Gorge. Oh, to be an Icelandic clam…

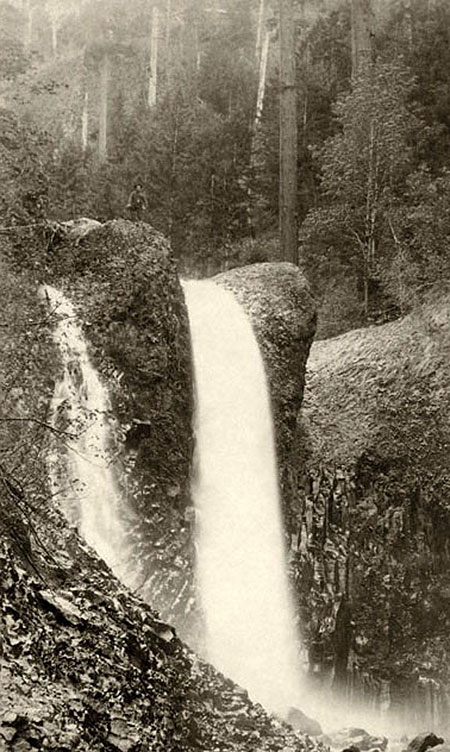

Yocum Falls and Tom Dick and Harry Mountain as they appeared after the Sherar Burn in the early 1900s

[click here for a larger view]

For many of us, the Eagle Creek Fire of 2017 feels like a redux of 2008 and 2011, when the Gnarl Ridge and Dollar Lake fires burned off forests on the east and north sides of Mount Hood, respectively. Just as fire crews worked this month to protect Multnomah Falls Lodge and the Vista House at Crown Point from fire in the Gorge, crews in 2008 and 2011 scrambled to protect iconic Cloud Cap Inn, the nearby Snowshoe Lodge and the many historic CCC structures at Tilly Jane from the fires.

For those of a certain age, the hike to Mirror Lake on Mount Hood once involved walking beneath hundreds of bleached snags reaching to the sky. These were the remnants of the Sherar Burn that scorched the entirety of Tom Dick and Harry Mountain, along with the upper Still Creek valley and points south in the early 1900s. The visible traces of this fire lasted prominently well into the 1980s, though the forest has largely recovered today.

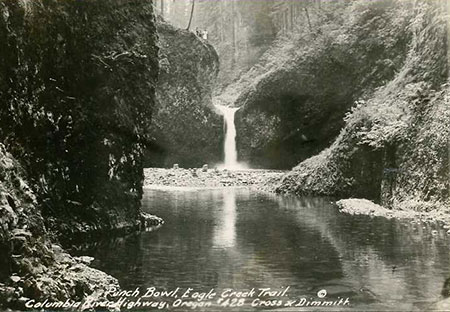

The prominent gravel bar at the base of Punch Bowl Falls on Eagle Creek in the early 1900s resulted from erosion from a nineteenth century fire.

The Eagle Creek Fire of 2017 in the Columbia Gorge will also follow this timeless sequence of destruction and renewal. There’s also some comfort to be gained from knowing that we’ve had a steady stream of fires in the Gorge, even in the very short timeframe of white settlement:

1902 – Yacolt Fire (238,000 acres)

1910 – Carson Fire (2,716 acres)

1917 – Stevenson Fire (7,606 acres)

1927 – Rock Creek Fire (52,500 acres)

1929 – Dole Valley Fire (202,500 acres)

1936 – Born Fire (7,897 acres)

1949 – Beacon Rock Fire (3,658 acres)

1952 – Skamania Fire (1,057 acres)

1991 – Wauna Point (375 acres)

1991 – Multnomah Falls Fire (1,200 acres)

1997 – Eagle Creek Fire (7 acres)

2000 – Oneonta Fire (5 acres)

2003 – Herman Creek Fire (375 acres)

2017 – Eagle Creek Fire (33,000+ acres)

The Forest Service reports that nearly all of the reported Gorge fires in recent decades (98%) have been human caused, but that certainly doesn’t mean the Gorge wouldn’t have burned without human behavior. The Forest Service describes the uniquely explosive fire conditions in the Gorge as follows:

“From early September through mid-October the west end of the gorge offers the best of all worlds from a fire’s perspective. The tremendous fuel loading of a west side forest coupled with hot and dry wind and incredibly steep terrain make for some of the most spectacular burning conditions the Pacific Northwest has to offer.”

Early white settlers to the Gorge called this “the Devil Wind” after the inferno that was the Yacolt Fire burned a quarter million acres on the north side of the river in less than 36 hours.

1991 Gorge Fires

Wauna Fire burning above Eagle Creek in 1991

Few remember it today, but in 1991 a pair of fires burned a sizeable stretch of the Oregon side of the Columbia River Gorge. The Multnomah Falls fire was a spectacular event, burning 1,200 acres along the Gorge wall from Multnomah Falls to Angels Rest, and nearly burning the historic Multnomah Falls Lodge. Sound familiar?

Multnomah Falls fire in 1991

The Multnomah Falls burn of 1991 has recovered quickly, and few hikers realize that the young forests along the popular Angels Rest trail were the direct result of the burn, though bleached snags still stand to tell the story. Visitors to Multnomah Falls still walk along the jumbo-size debris nets installed below the Benson Bridge to catch debris from the burned slopes of the 1991 fire, above. A major casualty of the 1991 fire was the beloved Perdition Trail that once connected Multnomah Falls to Wahkeena Falls on a route etched into the Gorge cliffs.

In 1991, the smaller Wauna Fire also burned 375 acres on the slopes directly above the west bank of Eagle Creek, below Wauna Point. This area has also largely recovered in the years since.

Early Fires in the Gorge

This unusual photo of Triple Falls from the 1890s shows snags from an earlier fire in Oneonta canyon in the background.

Early photos show that fire has been a routine part of the Columbia River Gorge ecology. That pattern changed with fire suppression efforts in the 20th century, which in turn, set the conditions for the catastrophic Eagle Creek Fire of 2017. Photos from Oneonta canyon (above) in the 1890s show slopes covered in bleached snags, suggesting a major fire sometime in the 1800s.

Shellrock Mountain’s east and south slopes were still recovering from fire in this 1940s view from the old Columbia River Highway.

Further east, places like the east slopes of Shellrock Mountain (above) were much less forested than today, thanks to repeated fires in the Gorge.

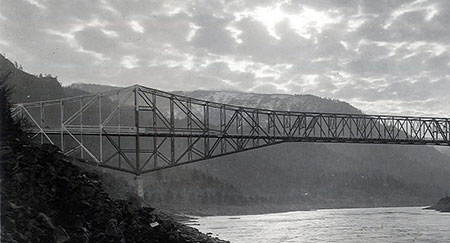

Snow covers the burned east slopes of Wauneka Point, the ridge that divides McCord and Moffett Creeks, in this 1930s view from Bridge of the Gods. This ridge burned again in the 2017 Eagle Creek Fire.

[click here for a larger view]

The above photo of the (then) new Bridge of the Gods in the early 1930s also shows large open slopes on Wauneka Point in the background, marked by winter snow. These slopes had largely reforested in subsequent years, but burned again in the Eagle Creek Fire of 2017, repeating a timeless cycle.

Burned over Aldrich Mountain and Hamilton Mountain in 1936.

[click here for a larger view]

Construction-era photos of Bonneville Dam in the late 1930s also provide detail on the state of the forests in Gorge at that time. The view north (above) shows burned-over Aldrich and Hamilton Mountains, both completely burned in the catastrophic Yacolt Burn.

Burned over Ruckel Ridge and Benson Plateau in 1937.

[click here for a larger view]

Looking to the southwest from the dam site, Ruckel Ridge and Benson Plateau (above) were also largely burned over in the late 1930s. These areas burned again in the Eagle Creek Fire of 2017.

1931-34 Lookout Survey: A History of Fires

Given that we’re stuck with relatively short stints on this planet, we humans do have the unique ability to record history for the benefit of our descendants. And it turns out that in the 1930s and early 1940s, early forest rangers in WyEast country did just that with a series of lookout tower panoramas.

This rich photographic resource was mostly forgotten until just a few years ago, when caches of these images archived in university photo collections were scanned and uploaded to the web in high resolution. They provide an astonishing, invaluable amount of detail, most from the years 1930-36.

Ironically, these panoramic images were captured as part of the massive U.S. Forest Service effort to prevent fires, with each set providing a 360-degree survey from the hundreds of lookout sites that were developed on public lands across the country.

In the Pacific Northwest, the panoramic photos provide an excellent glimpse into the way our forests had evolved for millennia, and before fire suppression took hold. The following are a few clips from this archive for places through the Mount Hood country and in the Columbia River Gorge.

Basin Point (1933)

Mount Hood from obscure Basin Point, now overgrown with trees.

[click here for a larger view]

Basin Point is largely forgotten today, but at one time this high spot north of today’s Timothy Lake provided a lookout location for the upper Oak Grove Fork basin. This lookout site probably wouldn’t have been used had it not been for a fire that had fairly recently swept over the butte, burning away a young forest that was still getting established here. The view is from the south edge of the Sherar Burn, a fire that swept across a large area south of Government Camp sometime in the late 1800s or early 1900s.

Buck Peak (1933)

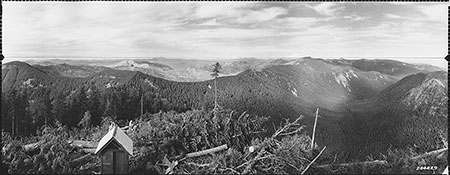

This view is from Buck Peak toward the burned-over Eagle Creek and Tanner Creek Valleys.

[click here for a larger view]

Today, Buck Peak is known for its sweeping views of Mount Hood and Lost Lake, but view (above) to the north from the former lookout site also shows the burned over Eagle Creek and Tanner Creek Valleys, with burned Tanner Butte as the prominent peak left of center. The upper slopes of the mostly unburned Lake Branch valley, to the right, also show signs of fire.

Bull of the Woods (1934)

The view looking southeast to Mount Jefferson from Bull of the Woods lookout shows a healthy mosaic of recent burns and recovering forest in the 1930s.

[click here for a larger view]

Fires have returned in recent years to Bull of the Woods, thanks in part to its wilderness protection that puts the land off-limits to timber harvesting (and thus “okay to burn” from a fire suppression perspective). This view looking toward Mount Jefferson shows a mosaic of recent burns and recovering forest, a healthy pattern that is returning with new fires in recent years.

Chinidere Mountain – North (1934)

This view looking north from Chinidere Mountain into the Herman Creek valley shows much of the drainage burned in the 1930s.

[click here for a larger view]

Today, the view to the north from popular Chinidere Mountain is gradually being obscured by recovering forests. This 1934 view shows the large burn that extended across the Herman Creek drainage at the time, from Benson Plateau (left of center) over Tomlike Mountain (right of center) toward Green Point Mountain (left edge of this photo). Though the forest here had almost completely recovered, much of the area in this view was burned again in the Eagle Creek fire of 2017.

Chinidere Mountain – West (1934)

This view west from Chinidere Mountain shows recovering forests in the Eagle Creek drainage.

[click here for a larger view]

This view looking west from Chinidere Mountain into the Eagle Creek drainage shows a recovering forest in the upper valley and on the adjacent slopes of Indian Mountain (to the left) and Tanner Butte (right of center).

This area was at the heart of the Eagle Creek and Indian fires in 2017, and much of the area shown in this view burned.

Devils Peak (1933)

This 1930s view from Devils Peak shows an extensive burn on Zigzag Mountain and lower slopes of Devils Peak.

[click here for a larger view]

The old lookout tower still survives on Devils Peak, located within the Salmon-Huckleberry Wilderness, but the view of Mount Hood has nearly disappeared behind the recovering forest. This 1930s view shows the extensive burn that encompassed the long ridge of Zigzag Mountain (center, in the distance) and lower slopes of Devils peak, in the foreground. Both areas have since mostly reforested in the era of fire suppression.

The west end of Tom Dick and Harry Mountain is the burned-over ridge extending below Mount Hood in this photo, part of the late 1800s Sherar Burn. The burned lower slopes of Devils Peak and upper Still Creek valley were also burned in this historic fire.

Green Point Mountain (1934)

This view from Green Point Mountain shows an extensive pattern of fires in the upper Herman Creek Valley.

[click here for a larger view]

In this view from Green Point Mountain, evidence of a mosaic burn stands out, with completely burned forest near the summit and surviving forest just below. The heavily burned slopes of Tomlike Mountain (center) and Chinidere Mountain (left of center) are in the distance are part of a wide mosaic of burns in the upper Herman Creek valley.

Old growth trees along Herman Creek today are proof that even large fires here didn’t completely burn the drainage. The Eagle Creek fire of 2017 burned a significant part of the Herman Creek drainage, and it is unknown how the old growth stands fared in the face of this recent fire.

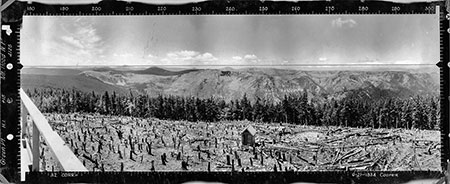

High Rock (1933)

The Abbott Burn encompassed the area surrounding High Rock, including the upper Roaring River drainage.

[click here for a larger view]

The view from High Rock looking north to Mount Hood was once surrounded by the extensive Abbott Burn, which engulfed much of the Roaring River watershed and part of the Salmon River backcountry sometime in the 1800s or early 20th century.

In the 1930s, a Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp was established on the shoulder of High Rock, and a small army of CCC workers planted thousands of trees across the Abbott Burn. Many survived, and much of the reforestation in the Roaring River valley resulted from this forest intervention effort. But the rocky high country of Signal Buttes and other nearby ridges are still largely open and covered in fields of huckleberries, with the forest recovery advancing much more slowly.

This pattern of open, regularly burned peaks and ridge alternating with lush canyon floors is the natural state of our forests. Lightning-caused fires regularly burn away forests surviving on the thin, dry soils found higher slopes and ridges, and larger trees in moist soils on lower slopes and canyon bottoms are better able to survive natural fires.

Lost Lake Butte (1933)

The burned upper slopes of Lost Lake Butte as they appeared in the 1930s, with Lost Lake in shimmering the distance.

[click here for a larger view]

Though the old-growth giants on the shores of Lost Lake have dodged or resisted fire for centuries, the forests on the dry, upper slopes of Lost Lake Butte were burned sometime in the late 1800s in a classic mosaic pattern that can be seen in the 1930s panoramic photos.

In the photo above, strips of larger, surviving trees can be seen within the burn, and a distinct line between the young,recovering forest in the burn area and larger trees that survived the fire is clearly visible along the near shore of Lost Lake. Raker Point (featured in the next photo) is visible as the open spur at the far right edge of the Lost Lake Butte panorama.

Raker Point (1933)

Hundreds of snags along the crest of Sawtooth Ridge and Raker Point (in the distance) show the extent of fire on the north side of Lost Lake, sometime in the late 1800s or early 1900s.

[click here for a larger view]

Raker Point is a little known peak located just north of Lost Lake, on the west end of Sawtooth Ridge (Raker Point is the distant open spur right of center in this photo). The ridge and Raker Point were burned sometime in the late 1800s or early 1900s, possibly in the same fire that scorched Lost Lake Butte. The recovery on Raker Point was well under way in the 1930s photos, with 10-20 year old seedlings rising up among the hundreds of bleached snags left from the fire.

Lost Lake was one of the earliest recreation destinations in WyEast country, with hardy visitors from the Hood River Valley making their way to campsites along the lake shore as early as the 1890s. In the 1920s, a “modern” dirt road was finally completed to Lost Lake, roughly along the same route as today’s paved highway.

Signal Buttes (1933)

Located west of High Rock, the Signal Buttes were completely burned in the Abbott fire of the early 1900s, and are still recovering today.

[click here for a larger view]

Today, the Signal Buttes are at the heart of the Roaring River Wilderness, and as described above, are still slowly recovering from the Abbott Burn fire that swept the area, despite efforts by the CCC in the 1930s to replant the forest here. The patch of unburned forest on the floor of the Roaring River valley (in the low area of the photo, below Mount Hood) are old growth Douglas fir and Western red cedar that survived the Abbot Burn — and likely many fires before that, as trees more than 1,000 years old are found here.

It’s also likely that the Signal Buttes will continue to be an open expanse of Beargrass meadows and Huckleberry fields if fires are allowed to burn here, once again. In this way, the Roaring River Wilderness is well on its way to a more natural condition of open ridges and a mosaic of old and recovering forests on the canyon floor and walls. Because the area was permanently protected as wilderness in 2009, future generations will have an opportunity to watch the forest here continue to evolve with fire, once again.

The rugged ridges and peaks just beyond Signal Buttes in this panorama are the high country of today’s Salmon-Huckleberry Wilderness. In contrast to the Signal Buttes, this northern extent of the Abbott Burn has largely recovered, with just a few peaks and ridgetops remaining as open Beargrass and Huckleberry fields.

Tumala Mountain (1933)

This view looking east from Tumala Mountain shows the burned ridges of the Salmon River and Roaring River high country in the 1930s. Mount Hood is on the extreme left.

[click here for a larger view]

This remarkable panorama from Tumala Mountain shows a burned-over landscape in much of what are today’s Salmon-Huckleberry (areas to the left) and Roaring River (areas to the right) wilderness areas. Most of this landscape is now heavily forested, with the exception of a few ridge tops and the crest of the Signal Buttes, described earlier and visible as the completely burned ridges in the upper right of this photo.

This photo also shows a healthy mosaic burn pattern on the nearby mountains immediate slopes, with bands of trees surviving between burned strips. This more natural fire pattern creates a rich habitat that, in combination with the series of lakes in the glacial valley at the foot of the peak, makes for an ideal landscape for wildlife.

You may notice that the photo markings on the left identify this as “Squaw Mountain”. In 2007, the Oregon Geographic Names Board renamed this peak out of respect for indigenous peoples, as the term “squaw” is considered derogatory. This change is part of a larger effort to rename other landmarks using “squaw” across the state. The word Tumala means “tomorrow” or “afterlife” in Chinook jargon, and is an apt name for this idyllic spot in WyEast country.

Summit Meadows (1930)

This 1930 view of Summit Meadows shows signs of an extensive fire along the south slopes of Mount Hood in the vicinity of Government Camp.

[click here for a larger view]

Early photos of Government Camp and Summit Meadows on Mount Hood’s south side show thousands of bleached snags marking a fairly recent fire in the area. These could mark a series of discrete fires or could be related to the larger Sherar Burn or the fires that swept Zigzag Mountain in roughly the late 1800s.

Extensive burns on Mount Hood above Government Camp in 1915 (Courtesy: History Museum of Hood River County)

The extent of the historic fires on Mount Hood’s south side is especially interesting given the degree of resort development here in the century since fire suppression began. The volcanic soils on Mount Hood’s south shoulder are among the youngest on the mountain, as much of the area was buried in fresh volcanic debris from eruptions that occurred in the late 1700s.

This makes the forests here especially vulnerable to fire because of the poorly developed soils, southern exposure and late summer stress from seasonal drought. Yet, the degree of development on this side of Mount Hood also makes it unlikely that forest fires will ever be allowed to burn naturally. Instead, these forests are good candidates for prescribed, controlled burns that could restore the forests to a more natural state while also protecting the hundreds of structures located here.

Tanner Butte (1930)

This 1930 view from massive Tanner Butte looks west through charred forests toward Tanner Creek canyon, the Bull Run Watershed (on the left) and Larch Mountain (on the right horizon).

[click here for a larger view]

Tanner Butte and its long northern ridge is a prominent landmark in the backcountry of the Columbia River Gorge, dividing the Eagle Creek and Tanner Creek drainages. The panoramic photos from 1930 show a heavily burned landscape in this area, and longtime hikers can still remember when the ridges around Tanner Butte were still covered with open meadows, as recently as the 1970s.

More recently, the forests had recovered across almost all of the burned areas shown in this panorama, but the Eagle Creek Fire of 2017 appears to have hit the Tanner Creek basin especially hard. This could be a result of the relatively young, even-aged forest here, but fire suppression almost certainly played a role in this fire becoming catastrophic.

Much of the area visible here is within the Mark O. Hatfield Wilderness, and will provide yet another laboratory for future generations to watch and learn from as the forest recovers.

Wildcat Mountain (1933)

The view from Wildcat Mountain toward McIntyre Ridge and Portland in the far distance.

[click here for a larger view]

Wildcat Mountain lies at the western edge of the Salmon-Huckleberry Wilderness, and Portland’s downtown high-rises are visible from its summit. Or, at least they were a couple of decades ago, before the recovering forests here enveloped the summit with a stand of Noble fir and Mountain hemlock.

Broad McIntyre Ridge (pictured in the distance in this photo) still has a few open Beargrass meadows with sweeping views of Mount Hood, but even here the forest is advancing rapidly.

The 1930s panoramic view shows a completely different landscape, with mixed stands of forests in the valleys below the Wildcat Mountain and its ridges that suggest a long history of mosaic burns. Without fire suppression, McIntyre Ridge and Wildcat Mountain would likely have burned again since the 1930s.

Since 1984, this area has been protected as wilderness, so future fires will likely be allowed to burn. If the recent Eagle Creek fire in the Gorge is any indication, the young forests that have grown since this panorama was taken are likely to be the first to burn, as we saw in the Tanner Creek and Eagle Creek areas.

Wolf Camp Butte (1933)

This view doesn’t exist anymore, thanks to a completely recovered forest on Wolf Camp Butte.

[click here for a larger view]

Wolf Camp Butte is another lookout site made obscure by the recovering forest that has completely covered the summit. More of a high spot than a peak, this 1933 view from the former lookout site provides us with an excellent look at the extent of the Sherar Burn. The canyon in on the right holds the Salmon River, descending from the Palmer Glacier on Mount Hood (just out of view to the left).

This fire burned north to present-day Government Camp and south to at least the Salmon River, encompassing a very large area. Parts of the Sherar Burn may have been replanted by the CCC in the 1930s, and the area is almost completely reforested today.

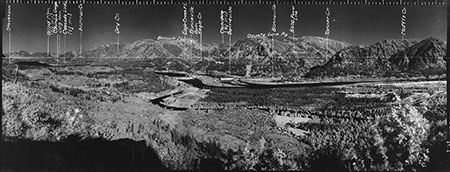

Wauna Point (1936)

This view is from Wauna Point on the Oregon side of the Gorge, looking toward Table Mountain on the Washington side.

[click here for a larger view]

This view from Wauna Point, directly above Eagle Creek, shows a long history of fire in the Gorge, with a mosaic forest pattern on the slopes of Table Mountain on the far side of the river that extends eastward toward Wind Mountain. The big trees on the Oregon side mark the Eagle Creek campground, a section of forest that also survived the recent catastrophic fire. The spot where this panorama was taken burned in the small 1991 Wauna Fire, and has since largely recovered.

1940s Gorge Lookout Surveys

In the years following completion of Bonneville Dam in 1937, a series of panoramic lookout photos were made from spots around the dam. Like the earlier 1930s panoramas, these photos provide a valuable snapshot of the state of forests in the Gorge at a time when fire suppression had just begun. They’re also nicely annotated with major landmarks identified!

Aldrich Butte – North (1941)

[click here for a larger view]

Like the view from Wauna Point on the Oregon side, this view toward Table Mountain shows a healthy blend of big trees that have survived periodic fires and more recently burned slopes covered on meadows and recovering forest.

Aldrich Butte nearly burned again in 2017, when embers from the Eagle Creek Fire floated more than a mile across the Columbia River and ignited a small fire here.

Aldrich Butte – South (1941)

The view south from Aldrich Butte toward Bonneville Dam and Oregon side of the Gorge.

[click here for a larger view]

This expansive view from Aldrich Butte shows the complex mosaic forest patterns created by repeated fires on Benson Plateau and “County Line Ridge”, which is now more commonly known as Wauna Ridge or Tanner Ridge.

This amazing photo not only shows how fire has shaped the forests on the upper slopes and ridges of the Gorge, but also how big trees in the canyons and at river level have often dodged or resisted fire.

Aldrich Butte – West (1941)

The view west from Aldrich Butte shows Hamilton Mountain (in Washington) and the steep wall of the Oregon side of the Gorge in the distance.

[click here for a larger view]

Like the view of Benson Plateau on the Oregon side, this view of Hamilton Mountain from Aldrich Butte shows a complex mosaic of forest types and ages that resulted from fire. On the far side of the river, the burned slopes of Wauneka Point can also be seen on the far left. Wauneka Point and the steep face of the Oregon side of the Gorge was heavily burned in the Eagle Creek fire of 2017.

Our Next Century with Fire?

There are so many variables at work in how we move from a century of forest fire suppression to — hopefully — an era where we learn to live with and appreciate the role of fire.

Will the public accept the inevitability of forest fires, and the implicit need to rethink building vacation homes and resorts in our forests? Will a return to sustainable, beneficial fires resume quickly, or will the catastrophic fires that suppression has set the stage for continue for decades or even centuries?

An even larger question is whether climate change will significantly accelerate the number of catastrophic fires? And how will climate change affect the ability for forests to regenerate in burned areas?

These are the difficult questions that future generations will be grappling with for decades to come.

Parts of the 2011 Dollar Lake Fire in the Mount Hood Wilderness burned in a beneficial mosaic pattern, as seen here at Eden Park. This is the goal of restoring the role of fire in our forests.

But signs of a shift in thinking are encouraging, starting with a broad consensus among forest scientists that fire suppression has been disastrous over the long term. Good public lands policy is always rooted in good science, and some of our scientists have also emerged to become influential leaders of agencies like the U.S. Forest Service and National Park Service, too. Let’s hope that continues.

Events like the Eagle Creek Fire of 2017 are also important learning opportunities for the general public. Over the next several decades, the millions who treasure the Columbia Gorge as their own “backyard” will have an unprecedented opportunity to better understand the role of fire in the Gorge ecosystem. Gorge land managers and advocates are already telling this story, as are local media outlets. That’s encouraging.

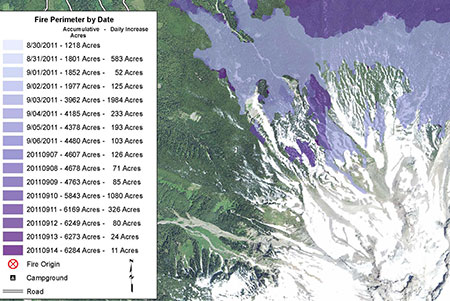

New mapping tools allowed land managers to document the daily progression of the 2011 Dollar Lake Fire with unprecedented detail. This information will be a gift to future generations of scientists and land managers.

New mapping tools that allow us to document fires in astonishing detail are also helping scientists better understand the dynamics of fires and forest recovery. This new level of documentation will help us move back to a sustainable relationship.

Even better, the flood of new fire mapping and data will be our gift to the future, helping future generations continue to better understand our forests, just as the lookout panoramas from the 1930s are helping us today. Hopefully, our actions now will ensure that future generations inherit forests that look more like those 1930s panoramas, as well.

From death comes renewal: huckleberry seedling growing from the bark of a tree in the burn area of the 2011 Dollar Lake Fire.

There’s good news on that front, too. Our youngest generations who had their first outdoor experiences on Mount Hood and in the Gorge will also be the scientists and policy makers of the future, and will steer public lands policy.

Their close-up experiences with fire in their formative years will surely drive their passion to move our forests back toward a health relationship with fire, so long as we all continue to learn and appreciate the essential role of fire in WyEast country.