Burned sign along Gorge Trail 400 in January (Tom Kloster)

State Park and Forest Service rangers and local trail volunteers have been busy this winter assessing the impact of the Eagle Creek Fire. A few photos have been released from their trips into the still-closed burn zone, showing extensive damage to many of our favorite Gorge trails. The early glimpses are sobering and much work clearly will be needed to begin reopening trails to the public. More importantly, they gave us the first sense of just how long it will take for the Gorge to recover — and it’s going to take awhile.

In early December, a far more comprehensive set of oblique aerial photos was captured by the State of Oregon as part of assessing the risks for landslides and flooding from the bare Gorge slopes. These amazing photos provide the first detailed look at how our most treasured places in the Gorge fared after the fire. This article features some of the most stunning of these startling images.

Weisendanger Falls and Multnomah Creek in better days (Tom Kloster)

My first reaction while first poring over the photos was shock and sadness. Like many of you, the Gorge was (and is) my second home, and it’s still hard to accept that the magnificent green Eden I grew up exploring has been destroyed. I’ll always long for the Gorge as it existing before the fire, even as I watch and learn from the miracle of forest recovery that will unfold in coming years. This is a paradox that we’ll all need to accept.

But moving forward, we also need to refocus our love for the Gorge of memories on the urgent work that lies ahead, not only to restore what was lost, but also set a new direction for how this amazing place can be sustainably managed in perpetuity. We owe it to future generations who will only know the old Gorge from our photos to never allow a man-made catastrophe like the Eagle Creek Fire of 2017 be repeated. The lesson from the fire is not just that it was human-caused, but that the fire and its severity resulted from our own unwillingness to set limits on how we manage and use the Gorge. This is our challenge moving forward.

____________________

This article is the first of a two-part series that features the best of the amazing new aerial photos. You can explore a large version of each photo in great detail by clicking on the “large view” link, which will open a 2000×1300 pixel version in a new window or tab. I’ve also enlarged some of the most fascinating highlights from these photos for the article.

Shepperd’s Dell to Multnomah Creek

The first half of the tour covers the west portion of the Eagle Creek Burn, beginning at Shepperd’s Dell, and moving east to the Ainsworth State Park area.

This photo is a birds-eye view looking down at the tiered waterfalls of Young Creek, in Shepperds Dell, and the iconic Historic Columbia River Highway bridge that spans the dell:

Aerial view of Shepperd’s Dell (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

Like so many areas within the burn, it sometimes seems like the fire sought out our most treasured places. In this case, the fire wrapped around Shepperd’s Dell, proper, killing trees on top of the domed rock formation at the east (left) end known as Bishop’s Cap and on the cliffs directly above Shepperd’s Dell.

In contrast, the area to the west of Young Creek and Shepperd’s Dell experienced a beneficial burn, with the understory cleared but many of the large conifers surviving:

Shepperd’s Dell, including the upper tier of the falls (State of Oregon)

This view also reveals the top tier of the four-step waterfall that cascades through the Dell. Though part if the second tier can be seen from the wayside, the tall upper tier is completely hidden by walls of basalt from below.

The historic bridge at Shepperd’s Dell was unharmed by the fire, but some of the stone walls along the west approach were damaged by falling trees, as shown in this view:

Aerial view of Shepperd’s Dell (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

The historic footpath that descends to the lower tier of waterfalls in Shepperd’s Dill is not significantly damaged, though it is vulnerable to falling rock and debris from the burned cliffs, above. Rangers have therefore closed this trail for safety reasons, for now.

This close-up view (below) shows the picturesque stand of Oregon white oak growing on a prominent basalt outcrop next to Shepperd’s Dell bridge. These trees were scorched by the fire, but still hold their browned foliage, so it’s unclear if these will survive. We’ll know if they leaf out this spring.

Historic Shepperd’s Dell bridge (State of Oregon)

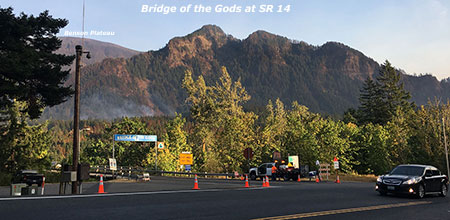

Next up, a photo that provides a close look at the popular Angels Rest trail. This view shows the north side, where the switchbacks along the upper section of the trail are clearly visible:

Aerial view of Angels Rest (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

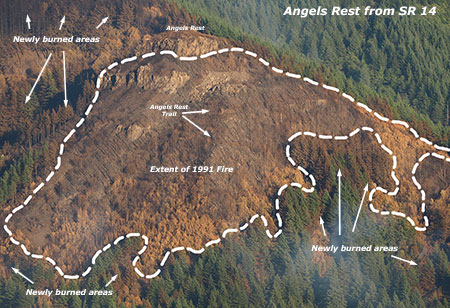

This part of Angels Rest burned in the 1991 Multnomah Falls Fire, and was still recovering last year when the Eagle Creek Fire swept through. A comparison of how these burns overlapped on Angels Rest is included in this earlier article on the fire.

One interesting lesson from the fire is how living trees don’t really “burn” thanks to their water content, even if a tree is killed by the heat. Instead, the wood in killed trees usually survives fully intact, becoming bleached snags as burned park peels off in the year or two following the fire. Because the unburned wood is so sound, snags from fires as far back as the early 1900s are still standing in many places around the Cascades.

Yet, many of the dried-out, bleached snags from the 1991 Gorge fire were burned to nothing but stumps of charcoal. This was true throughout the burn, where dead trees and old snags from previous fires were reduced to ashes in places while nearby living trees often survived the fire with only a blackened trunk.

Detailed view of the Angels Rest Trail (State of Oregon)

This photo shows Angels Rest from the west, also with the upper switchbacks along the trail leading to the summit:

Aerial view of Angels Rest (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

While the north side of Angels Rest burned hot enough to char the landscape down to blackened soil, the west side fire seems to have been less intense, with much of the understory appearing to survive, and many of the old snags from the 1991 burned black, but still standing along the lower edge of this close-up view (below).

Detailed view of Angels Rest Trail (State of Oregon)

Moving east, the next photo shows the fire’s impact on Wahkeena Falls, among the more hallowed spots in the Gorge. While the burn affected slopes on both sides of the falls, much of the forest here survived the flames.

Aerial view of Wahkeena Falls (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

A closer look shows Lemmon’s Point (the overlook east of the falls) to have burned, along with the steep cliffs to the west of the falls. Other photos in the set show the Wahkeena Trail above the falls to be heavily affected by the fire, with a lot of debris and fallen trees covering this iconic trail.

Detailed view of Wahkeena Falls (State of Oregon)

News coverage has provided many views of Multnomah Falls since the fire began, but the new set of aerial views gives a much better look at the impact of the fire on the area. Like Wahkeena Falls, the fire here raged around the falls but left many of the big trees scorched, but alive.

As shown in this photo, the most heavily impacted area near the falls is along the cliffs east of Multnomah Creek, where the Larch Mountain Trail begins its many switchbacks to the top of the falls, and on the steep slopes directly above the falls:

Aerial view of Multnomah Falls (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

This close-up view shows the low bluff to left of the falls to have been more significantly impacted. The Larch Mountain trail passes through this section of burned forest:

Close-up view of fire damage below Multnomah Falls (State of Oregon)

This photo shows a bit more of the west side of the falls and a peek into the Multnomah Creek canyon, above Multnomah Falls:

Aerial view of Multnomah Falls and lodge (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

A closer look at this photo (below) shows burned trees along Multnomah Creek, just above the falls, and along the ridge to the east of the falls that marks the high point for hikers following the Larch Mountain Trail to the viewpoint at the top of the falls. The Forest Service reports that the viewing platform there was undamaged by the fire, though the spur trail to the viewpoint has been impacted by falling debris.

Close-up view of the canyon just above Multnomah Falls (State of Oregon)

This photo from just east of Multnomah Falls (below) provides a better look at the slopes where the Larch Mountain Trail scales the Gorge wall. Here, a mosaic burn has left many trees standing, which bodes well for this steep slope holding together as the recovery begins, but will also mean years of falling debris from killed trees and loose slopes for trail crews to clear.

Aerial view of the east side of Multnomah Falls (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

This close-up look at the photo reveals the upper switchbacks of the Larch Mountain Trail as it approaches the ridge crest:

Close-up view of the Larch Mountain Trail where it climbs to the top of the falls (State of Oregon)

One of the challenges here will be keeping hikers on the trail, as switchback cutting has been a perennial problem in the Gorge, and especially along this very popular route. The fire provides an opportunity to better educate visitors about the damage that cutting trails can cause, but will require close coordination among state and federal land managers, and help from trail advocates.

This photo (below) provides a view down Multnomah Creek canyon from (roughly) above the Wahkeena Trail junction, and gives a good sense of how the forests here fared. Though heavily burned, much of the burn pattern is still a mosaic pattern. If the living trees in this photo survive their first summer of drought stress after the fire, they should recover quickly and help the surrounding forest regenerate.

Aerial view of Multnomah Creek canyon (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

This closer look at the photo (below) gives an excellent sense of how fire affects forests in a mosaic burn. While some trees were killed outright by the heat of the fire, others survived with some or all of their living canopy intact.

Close-up view of the burn along Multnomah Creek (State of Oregon)

When fires are hot enough to explode into tree canopies, fire fighters call this “crowning”, and it almost always means the tree will die. Less heat means that the cambium layer can survive under thick-barked older trees, and fires that don’t rage into the crowns of trees allow foliage to survive, as well.

If the fire burns low to the ground and with less heat, trees like Douglas fir have evolved to have thick, fire-resistant bark that can survive this stress. Even in a relatively small area, as shown in the above photo, all of these fire behaviors can play out leaving a mosaic of living and killed trees. The mosaic effect, in turn, not only allows for a faster rebound of the burned forest and less erosion, but also provides a more diverse ecosystem that benefits the most plant and animal species. Before our intervention over the past century of fire suppression, mosaics from fire were the normal state of our forests.

This is the crux of why prescribed burning — the practice of purposely setting forest fires in a controlled manner to reduce fuels and rejuvenate the understory — is the most ecologically sound path forward for the Gorge. Prescribed fires are usually set in late fall, when the approaching rainy guarantees a short burn and cooler weather encourages fires that are less hot and burn closer to the ground.

For the next photo (below), you’ll need to adopt the perspective of a dive-bombing bird, as this is a near-vertical view of Weisendanger Falls (the splash pool is at the bottom of the photo) on Multnomah Creek (which flows up in this view). This is the first big waterfall above Multnomah Falls, and though a few trees around the falls were scorched, the forest canopy here mostly survived.

Aerial view of Weisendanger Falls on Multnomah Creek (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

A closer look at this photo (below) shows the Larch Mountain Trail switchbacks that climb above the creek at Weisendanger Falls. Like the switchbacks on lower parts of the trail, this area will require some diligence to keep hikers cutting the switchbacks in the absence of an understory that was burned off in the fire.

Education will be key, as there are simply too many burned switchbacks throughout the Eagle Creek Burn to protect with barriers or other physical means, and these fragile slopes will only recover if they’re left undisturbed.

Close-up view of the trail below Weisendanger Falls (State of Oregon)

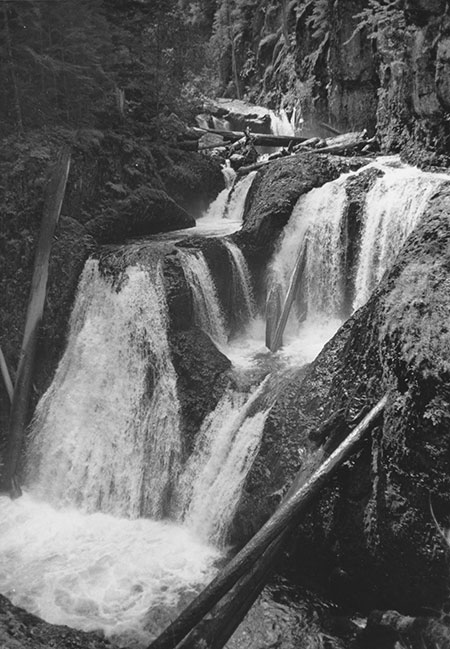

To give a sense of what happened here, this is what Weisendanger Falls looked like from the first switchback along this section of trail a few years ago, before the fire. The good news is that many of the tall conifers here survived the fire, though the lush understory in this old view will take many years to recover.

Stately Weisdanger Falls before the fire (Tom Kloster)

Here’s another birds-eye photo of Multnomah Creek, just upstream from the previous image. This view shows Ecola Falls at the center, the third and final large waterfall on Multnomah Creek, with the creek flowing to the left in this view:

Aerial View of Ecola Falls on Multnomah Creek (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

A closer look at the photo (below) shows the brink of Ecola Falls more clearly (on the left side of the image), as well as the burned-off cliffs at the top of the photo, above the falls. What shows up here as a brown slope is actually a basalt wall that was once covered in green moss and ferns — you can see a surviving sliver of moss clinging to a vertical section of the cliff in the upper left corner of the photo.

Close-up of the top of Ecola Falls (State of Oregon)

While it won’t happen overnight, the “re-mossing” of burned cliffs and talus slopes in the Gorge will occur in the relative near term of the next decade or so. How do we know this? From recent rock falls and slides in the Gorge, where raw surfaces have been “re-greened” after just a few years of exposure to the cool, wet rainforest environment.

What did Ecola Falls look like before the fire? Most never saw the falls from stream level, as the Larch Mountain Trail passed above the brink of the falls atop a high cliff. But a steep descent into the canyon provided this stunning view for waterfall chasers:

Beautiful Ecola Falls before the fire (Tom Kloster)

The understory burned away here, too, though many of the large conifers around Ecola Falls survived. Trees killed by the Eagle Creek fire will eventually drop into Multnomah Creek and in the future, and for many decades to come, we will see log piles accumulate below the major waterfalls.

While this may take some getting used to, log piles were a normal part of stream ecology before fire suppression and logging. This scene along a wild section of Mount Hood’s Salmon River is typical of what our waterfalls once looked like:

Log-filled Frustration Falls on the Salmon River in the early 1960s (USFS)

Beyond aesthetics, in recent years stream ecologists have learned that logs and woody debris in streams are an essential ingredient to healthy fish habitat. So in this way, we’re simply returning to the way things have always been in the Gorge, and the coming wave of logs is only new to our eyes.

This photo is from below Larch Mountain, looking down Multnomah Creek toward Multnomah Basin, in the distance. Large stands of old-growth forest dodged the fire here:

Aerial view of upper Multnomah Basin (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

A closer look at this photo (below) shows the Larch Mountain Trail where it traverses a large talus slope along Multnomah Creek:

Close-up of the Larch Mountain Trail and Multnomah Basin

In many areas, the fire seems to have skipped over talus slopes like this, hopefully allowing the unique, low elevation population of Pikas that live in these areas of the Columbia Gorge to survive the burn. We’ll know soon enough, as the Gorge Pikas are active year-round, and their distinctive “beep” is unmistakable for passing hikers.

What did upper Multnomah Creek look like before the fire? Here’s a view of the big conifers that lined much of the creek before the burn:

Upper Multnomah Creek before the fire (Tom Kloster)

In many areas, these trees seem to have survived, though many were lost to the fire. We’ll know the full impact of the fire in the next year or two, after trees that survived the burn have faced their first summer drought and subsequent winter season.

Oneonta Creek to Ainsworth State Park

The following series of images are especially tough to look at. For many, Oneonta Creek is (or was) second only to Eagle Creek for its spectacular waterfalls, famous slot gorge and — until now — magnificent forests. All of this has changed.

As the following photos show in jarring detail, the forests of the lower Oneonta Creek canyon were almost completely destroyed by the fire, with only a few scattered trees surviving. Worse, many of these surviving trees are still fire damaged and likely to die under the added stress of drought next summer.

This photo (below) looks up the canyon from the mouth of Oneonta Gorge, and tells the hard story: a few trees on the west slope of the gorge survived, but the canyon beyond is completely burned. Scorched Oneonta Falls can be seen at the head of mile-long Oneonta Gorge in this view:

Aerial view of the devastation at Oneonta Gorge (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

A closer look at Oneonta Gorge (below) shows the devastation more clearly. One of the obvious impacts of the fire is that the infamous logjam at the lower entrance to the gorge is about to get a LOT bigger, as burned logs begin to roll into Oneonta Creek by the hundreds over coming decades.

While the logs will benefit the ecological health of the creek, the logjam in Oneonta Gorge could prove catastrophic to the historic highway bridges downstream, as described in this earlier article on the blog. The fire may finally spur some sort of intervention by ODOT and the Forest Service to remove the logjam.

Close-up of Oneonta Gorge (State of Oregon)

The aftermath of the fire also provides the Forest Service with an opportunity to finally close Oneonta Gorge to swarms of teenage waders who overwhelm this place each summer. It’s time give this precious place a much needed rest from the crush of people who have “discovered” it in recent years, and in the long-term, severely restrict access with an enforced permit system.

The summer conga line of kids waiting to cross the logjam at Oneonta Gorge (photo: John Speth)

The fire also burned away the wood lining of the recently restored Historic Highway tunnel at Oneonta Bluff, on the left in the above photo, and shown in the photo below. This is another opportunity for a reboot of this historic feature.

Oneonta waders had already destroyed the historic tunnel before it burned in last year’s fire (Tom Kloster)

ODOT should absolutely rebuild the historic wood lining, but as thousands of young people proved by thoughtlessly carving their names and messages into the soft cedar surface, the public can’t be trusted with uncontrolled access to this restored treasure.

If it is rebuilt, the tunnel must be securely gated, and only opened on weekends when visitors can be monitored by agency staff or volunteer. This is one of many examples where we have a unique opportunity to set limits on how we use the Gorge, and ensure we pass it along to future generations in better shape than what we inherited.

This photo of Oneonta Bluff, taken above the tunnel and east of Oneonta Gorge, shows a few interesting details on the behavior of the fire:

Aerial view of Oneonta Bluff (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

This close-up view (below) from the left side of the photo shows how the fire burned away a segment of the cliff face, while leaving ferns, moss and a few trees clinging to an untouched section of cliff, just feet away. The understory at the top of the cliff was completely burned, but a stand of Douglas fir survived to help begin the recovery here. The Horsetail Creek trail passes through this stand of trees on Oneonta Bluff.

Close-up of burn patterns on Oneonta Bluff (State of Oregon)

A closer look at the burned crest of the bluff (below) shows trees cut several feet above the ground. These trees were removed after the fire because of their falling hazard to the highway below, not as part of the fire fighting effort:

Logged trees above the historic highway on Oneonta Bluff (State of Oregon)

This photo of the entrance to Oneonta Gorge (below) shows the cliff walls inside the gorge green and intact — an encouraging sign that the rare plant and animal species that live here may have survived the burn.

Aerial view of the logjam in Oneonta Gorge (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

A closer look at this photo (below) shows the logjam at the entrance to Oenonta Gorge already growing with new logs released by the fire:

Close-up view of the logjam in Oneonta Gorge (State of Oregon)

This close-up view (below) shows good detail of trees that survived the fire on the cliffs above Oneonta Gorge, despite having their lower trunks burned black in the blaze:

Trees that survived the flames on the cliffs above Oneonta Gorge (State of Oregon)

Moving upstream, this photo (below) provides startling detail of the Oneonta Trail, much of it heavily impacted by the fire. This photo also shows the lower Oneonta footbridge, located just above Oneonta Falls where it drops into the narrow slot of Oneonta Gorge:

Aerial view of the devastation above Oneonta Gorge (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

Sadly, the forest was completely killed in this idyllic spot. In this close-up view of the photo (below), Oneonta Bridge Falls, the small cascade above the bridge, can be seen with the first of what will be many more logs filling this stream in decades to come. And while the lower Oneonta footbridge seems to have survived the fire intact, the steep, terraced switchbacks climbing the canyon east of the bridge appear to be heavily impacted by erosion that followed the fire.

Close-up of the fire damage above Oneonta Gorge (State of Oregon)

What did this spot look like before? This is the verdant scene that existed here until last September, as viewed from the footbridge looking downstream at the brink of Oneonta Falls where drops into the narrow gorge, beyond:

Looking over the top of Oneonta Falls and into Oneonta Gorge before the fire (Tom Kloster)

How soon will this area recover? The forests will take decades to return to Oneonta canyon, but the understory will bounce back much more quickly. In this close-up view from the aerial photos, ferns and moss on the steepest walls of the canyon near the lower Oneonta Bridge survived the fire, and will help fuel the recovery here:

Close-up of the lower Oneonta footbridge (State of Oregon)

This close-up view (below) of the terraced switchbacks to the east of the lower Oneonta footbridge shows Licorice ferns surviving along the vertical stone walls, marking the otherwise buried trail:

Close-up of the steep switchbacks on the east side of the bridge (State of Oregon)

Another surprising lesson from the fire is the important role of the ubiquitous Licorice fern and the moss carpets they inhabit in holding loose rock and talus slopes together in the Gorge. These tiny plants are the living glue that keep the Gorge slopes intact. Fortunately, these will also be among the first plants to return to burned areas.

This photo (below) captures Oneonta canyon from Oneonta Bridge Falls (at the bottom, marked by a log lying across the falls) to little-known Middle Oneonta Falls, in the huge basalt cavern at the top of the photo. The terraced switchbacks above the lower Oneonta footbridge can also be seen in the lower left corner of this view:

Aerial view of devastated Oneonta Creek canyon (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

This closer view (below) gives a good sense of what we can expect to see over the next few years throughout the burn zone: deep erosion where burned trees and an absence of understory vegetation leaves steep slopes exposed. This view shows a small landslide that has already toppled several burned trees into the canyon:

Close-up view of a landslides triggered by the fire (State of Oregon)

Waterfall explorers have long visited beautiful Middle Oneonta Falls and its deep cave by following a steep, sketchy boot path on the west side of the canyon. In recent years, a major landslide not only took out the Oneonta Trail, proper, but also this little-known boot path, completely blocking the descent to the middle falls.

This photo of Oneonta canyon (below) shows what waterfall lovers have dreamed of for years: a clear route for a future trail along the east bank of the creek to Middle Oneonta Falls. While the fire has impacted the forest here for generations to come, it also brings an opportunity to enhance the trail network as part of the restoration with a once-in-a-century view of the landscape laid bare.

Aerial view of little-known Middle Oneonta Falls (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

These close-up views (below) from the previous photo show Middle Oneonta Falls in fine detail. The forest and understory here were completely destroyed by the fire:

Middle Oneonta Falls (State of Oregon)

Middle Oneonta Falls and its huge cave (State of Oregon)

What did Middle Oneonta Falls look like before the fire? It was among the most idyllic spots in the Gorge, though rarely seen. Here’s a photo from better days, when it was a sylvan paradise:

Beautiful Middle Oneonta Falls before the fire (Tom Kloster)

The grove of Douglas fir on the left side of this image were 50-70 years old before the fire destroyed them, so while I won’t live to see this scene restored, many in today’s Millennial generation will. It’s difficult to confront the loss, but these images from before the fire will be important for younger generations as a visual reminder of what coming the Gorge restoration is working toward.

The following is perhaps the most difficult to view of the new aerial photos of Oneonta canyon. This view shows Triple Falls, the best-known scenic highlight of the Oneonta Trail and one of the most photographed, picturesque scenes anywhere. The fire killed the entire forest and completely erased the understory here:

Aerial view of the devastation at Triple Falls (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

This closer look at the photo (below) shows the braided spur trails leading to the exposed viewpoint opposite the falls. The fire burned hot here, rolling into the crowns of many trees, as indicated by blackened bark extending to the tops of tree trunks:

Close-up view of Triple Falls and the viewpoint trail (State of Oregon)

What did Triple Falls look like before the fire? It was one of the most visited and iconic scenes in the Gorge. Only today’s younger Millennials will see anything like this again in their lifetimes:

The iconic scene at Triple Falls before the fire (Tom Kloster)

The upper Oneonta footbridge at Triple Falls was also heavily damaged by the fire, and may be completely compromised. As this close-up view (below) shows, the decking and railings are completely burned away, and the log span may also be burned beyond repair:

Burned-out upper footbridge above Triple Falls (State of Oregon)

The burned-away understory (below) also reveals lost trail segments at the Triple Falls viewpoint. A close look at this image shows an upper, abandoned trail alignment (complete with stone wall) that likely dates back to the Civilian Conservation Corps, but had been lost in the undergrowth. The modern route is the most prominent trail in the center of this trail maze:

Network of new and old trails at the viewpoint revealed by the fire (State of Oregon)

The burn gives the Forest Service an opportunity to rethink and redesign the trails at this overlook, where heavy foot traffic was already causing serious erosion and loss of vegetation, even before the fire swept through last fall.

This photo (below) of the upper Oneonta Canyon shows that it fared better than the steep lower canyon in the fire, as revealed in this view from above the confluence of Oneonta and Bell creeks:

Aerial view of upper Oneonta canyon at Bell Creek (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

A closer look at this photo (below) shows a mosaic burn, with large stands of ancient conifers surviving the blaze, while others were less fortunate:

Close-up of ancient forests in the upper Oneonta canyon (State of Oregon)

Another close look at this photo (below) shows that the fire often killed young, recovering forests (from past fires) while older, nearby stands survived:

Burn pattern detail in the upper Oneonta Canyon (State of Oregon)

While counter-intuitive at first glance, this is another important lesson from the Eagle Creek fire: part of the natural selection process in our forests is the ability for trees to grow fast, large and tall enough to survive periodic fires, thus surviving to generate the seedlings that will begin the recovery of the surrounding burn.

Moving east from the tragically scorched Oneonta canyon, the scene along nearby Horsetail Creek is somewhat less devastating, as this photo from above Horsetail Falls shows:

Aerial view of Horsetail Falls and canyon (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

A closer look (below) at familiar Horsetail Falls shows many of the big conifers around the falls surviving, even though the fire swept down to the edge of the Historic Columbia River Highway. The Horsetail Creek Trail can be seen climbing the slope to the left of the falls in this view, and appears to be somewhat impacted by falling trees and debris.

Close-up of the fire impact on Horsetail Falls (State of Oregon)

This close-up view of the photo (below) shows the sharp contrast in the severity of the burn in the Oneonta canyon (blackened area to the right) and the Horsetail canyon (mosaic burn to the left). This detail shows how topography and wind patterns work together to determine the path and severity of forest fires:

Contrasting burn patterns along the divide between Horsetail and Oneonta canyons (State of Oregon)

Fans of the informal Rock of Ages trail will find rough going in the future along this informal route that climbs above Horsetail Falls. In this close-up view (below), the entire ridge appears to be burned over. Because the trail is not officially recognized or maintained, falling debris and erosion will take a toll on this route, even if hikers work to keep the unofficial route open.

Fire impact on Rock of Ages ridge (State of Oregon)

This vertical photo (below) of Horsetail Falls and Ponytail Falls from directly above shows that much of the forest canopy along the lower section of Horsetail Creek survived the fire:

Birds-eye aerial view of Horsetail Falls and Ponytail Falls (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

A closer look (below) at this photo shows a few killed trees near Ponytail Falls, but mostly a green canopy sufficient to carry most of these trees through next summer’s drought and to long lives ahead:

Close-up of Ponytail Falls showing the scope of the burn (State of Oregon)

What did Ponytail Falls look like before the fire? It was yet another green grotto in the Gorge, framed by graceful stands of Vine Maple. It’s unknown if these small understory trees survived the fire:

Graceful Ponytail Falls on Horsetail Creek in better days (Tom Kloster)

Like the upper Oneonta canyon, the upper Horsetail Creek drainage is largely a mosaic burn. This photo (below) shows large sections of surviving trees that will greatly benefit forest recovery here:

Aerial view of Horsetail canyon, above the waterfalls (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

A close look at this photo (below) shows Archer Mountain on the Washington side of the Gorge. This view gives a good sense of just how massive the Eagle Creek fire really was, as embers from the fire were carried more than a mile across the Columbia River where they ignited a small fire on the slopes of Archer Mountain.

Closer view of Horsetail Canyon and Archer Mountain, across the Columbia River (State of Oregon)

Firefighters were briefly concerned with the possibility of the fire spreading broadly across the Washington side of the Gorge, but managed to contain the fire to a few acres on Archer Mountain.

The final photo (below) in the first part of this series shows Yeon Mountain and Katanai Rock in the Ainsworth State Park area. The small community of Dodson spreads out at the base of the 3000-foot high Gorge wall in this area:

Aerial view of Yeon Mountain and Katanai Rock (State of Oregon)

[click here for a large photo]

The fire was surprisingly agile here, burning ancient trees perched on remote ledges across the 3-mile long cliff face here (below). The vertical topography protected many old trees, too, where many isolated giants remained out of reach from the flames. The geology of this area is notoriously unstable, with frequent rock falls and mudflows. The loss of forests to fire here is expected to accelerate erosion for decades to come.

Close-up view of burn pattern on Katanai Rock (State of Oregon)

One such mudflow spilled down these slopes in the 1990s, burying a farmhouse to the second story and spreading across Interstate-84, closing the freeway for days. This mudflow had since grown a dense stand of Cottonwood and Red Alder trees (below), obscuring the abandoned, buried farmhouse over the past quarter century.

Detailed view of the 1990s landslide near Dodson, now burned over by the Eagle Creek Fire (State of Oregon)

Surprisingly, the Eagle Creek Fire seemed to seek out this young stand of trees, burning it entirely, and finally destroying what was left of the old farmhouse, which can be seen as a rectangle of white ashes in the close-up view, above. Older conifer forests (on the right) bordering the mudflow survived the flames, as did irrigated fields where fence lines served as firebreaks. Scenes like this help us better understand how fires shape the evolution of our forests over time.

Looking ahead…

These photos are hard to look at. For so many of us, the Gorge is a sacred place where we go to escape the stress of urban life and ground ourselves in the perfection and serenity of nature at its most sublime. Seeing the once lush, green landscape reduced to blackened tree skeletons and ashes is shocking, to say the least.

But moving forward, every year will mark what is expected to be a rapid recovery. It also offers us a chance to be part of the recovery. If the 1991 Multnomah Falls Fire is our guide, we’ll see young trees established within a decade and new forests well on their way to maturity by the time today’s Millennials begin receiving their Social Security checks.

That’s reassuring, as learning to understand our place in the natural landscape begins with accepting that we are just passing through ecosystems that existed long before us, and will thrive long after we are gone. Our role is to ensure that future generations inherit healthy, thriving ecosystems that are enhanced by our actions, not harmed by them.

Sword fern front sprouting from its roots after being scorched by the fire (Tom Kloster)

In the meantime, you can do something about the Gorge recovery right now! How? Sign up for a Trailkeepers of Oregon (TKO) trail project. TKO already has several events lined up beginning in February, and there will be many more events to coming for years to come.

This is a great way to give back and be part of restoring our Gorge trails, and no experience is required — just an able body and passion for the Gorge! If you can dig in your garden or rake leaves, you can be a volunteer on a trail crew. You can also support TKO with a donation through their website.

Next up in Part 2 of this article: McCord Creek, Moffett Creek, Tanner Creek, Eagle Creek and Shellrock Mountain.

________________

Author’s note about the photos: a friend of the blog pointed me to the amazing cache of photos featured in this article, and while you could probably acquire them from the State of Oregon, I would encourage you to let our public agency staff focus their time on the Gorge recovery, not chasing down photo requests.

With this in mind, I’ve posting the very best of the photos here, and have included very large images for those looking to use or share them. These photos should be credited to “State of Oregon” where noted in this article, not this blog. They are in the public domain.

________________