The Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) is set to begin construction of more than $27 million in road widening projects along the Mount Hood Highway in 2010 and 2011. These projects are supposed to improve safety along the segment of Highway 26 located east of Rhododendron, and along the Laurel Hill grade. In reality, they will do little more than speed up traffic, and perhaps even make the highway less safe as a result.

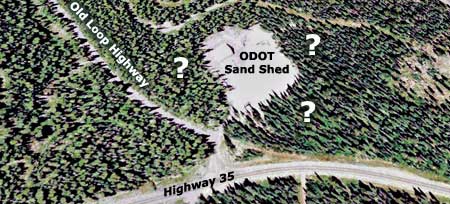

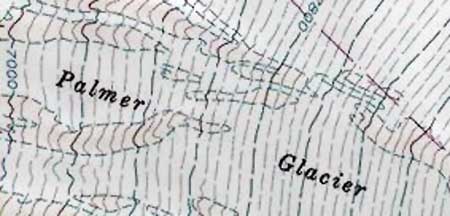

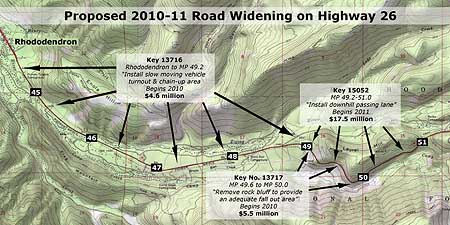

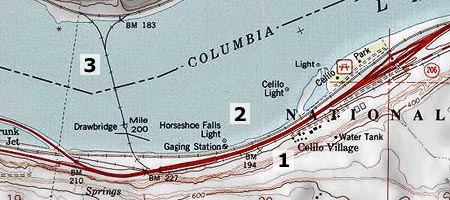

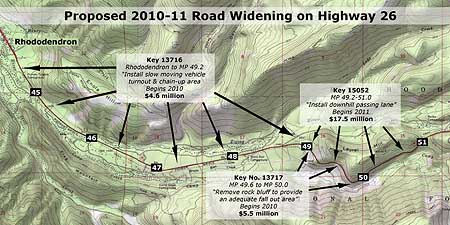

There are a total of three projects proposed for the Mount Hood corridor in this round of funding, including two “safety” projects that would widen the highway, and a third “operations” project that appears to be driven by the other two “widening for safety” proposals. The projects and their ODOT key numbers are shown on the map below.

Three projects are proposed for Highway 26 in 2010-11 that will add capacity to the road, though only if you read the fine print

(click here for a larger map)

The most alarming of the projects in this round of road widening is a proposed downhill passing lane on Laurel Hill, supposedly making it “safer” for throngs of Portland-bound skiers to pass slow vehicles on the downhill grade on busy weekends. This project is a repeat of the outmoded “widening for safety” philosophy that has already impacted the lower sections of the corridor, and was described in Part One of this article.

The ODOT project details for the “downhill passing lane” are sketchy, but such projects generally assume that drivers forced to follow slow vehicles become frustrated, and attempt to pass in an unsafe manner — a potentially deadly decision on a winding, steep mountain road. But is the answer to build a wider, faster road? Or should ODOT first use all of the other tools available to manage the brief periods of peak ski traffic before spending millions to cut a wider road into the side of Laurel Hill?

The answer to these questions seem obvious, but in fact, ODOT is moving forward with the most expensive, environmentally destructive options first, in the name of safety.

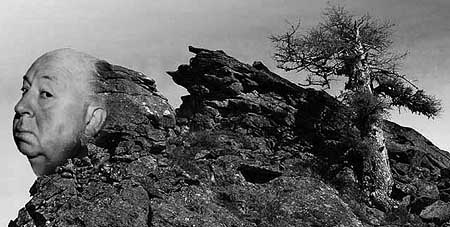

The westward view of the Laurel Hill Grade in a section proposed for widening to allow a downhill passing lane. The newly protected wilderness of the Camp Creek valley spreads out to the left.

A better solution, at least in the interim, would be to employ some of the less-expensive, less environmentally degrading approaches that have been successfully used elsewhere in the corridor. One option could be simply enforcing the current 55 mph speed limit and no-passing zones, for example, which would be much more affordable than the millions proposed to widen the highway in this difficult terrain.

Another possibility could be to extend — and enforce — the 45 mph safety corridor speed limit east from Rhododendron to the Timberline Junction, in Government Camp. Enforcing this slower 45 mph limit would result in skiers spending only an additional 90 seconds traveling the nine-mile section of Highway 26 from Government Camp to Rhododendron. This would seem a reasonable trade-off in the name of safety, especially compared to the millions it would cost to build downhill passing lanes on this mountainous section of highway.

The view east (in the opposite direction of the previous photo) where road widening is proposed to add a fourth downhill lane, carved from the sheer side of Laurel Hill.

Delaying the current road-widening proposals and taking a less costly approach to improving safety would also allow ODOT to more fully evaluate the effects that growing traffic on Highway 26 is having on the surrounding area. And while it is true that delaying a project that has already moved this far in the ODOT funding pipeline is an uphill battle, it is also true that a more fiscally conservative approach is clearly more consistent with the agency’s own transportation policy than the costly widening projects that are proposed.

However, while the visionary Oregon Transportation Plan (OTP) calls for a departure from old school thinking when it comes to new highway capacity, it does not establish a detailed vision for the Mount Hood Highway. But the general direction provided by the OTP does support a least-cost approach to managing highways, and slowing down the latest road widening proposals in the Mount Hood corridor would be consistent with that policy.

Unfortunately, the badly outdated Oregon Highway Plan (OHP) sets the wrong direction for the Mount Hood Highway, emphasizing speed and road capacity over all else. But until a better vision is in place for the highway, the response by ODOT planners and engineers to safety concerns and traffic accidents in this corridor will be more road widening projects sold as “safety improvements.”

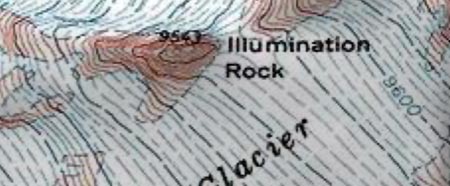

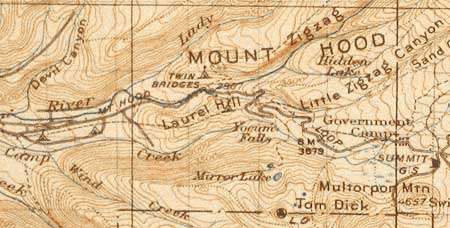

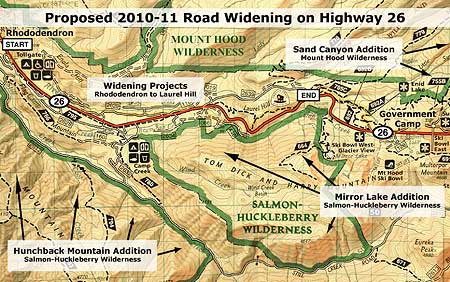

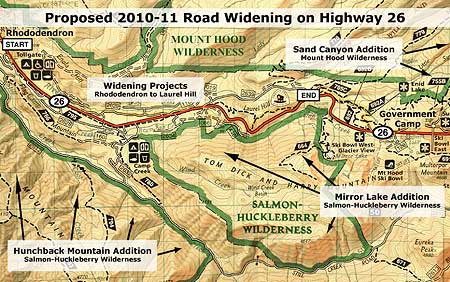

Both the Salmon-Huckleberry and Mount Hood wilderness areas saw major expansions in 2009 that were not considered in the proposed ODOT expansion projects for Highway 26

(click here for a larger map)

Over the years, this old-school approach has already created a road that is rapidly approaching a full-blown freeway in size and noise impacts on surrounding public lands. At the same time, the pressure to minimize highways impacts on the forest surroundings is still growing.

In 2009, wilderness areas around Mount Hood were significantly expanded, and the new boundaries now draw close to the highway along the Laurel Hill grade, where the “safety” widening is proposed. What will the noise impacts of the proposed highway expansion be on the new wilderness?

Already, highway noise dominates the popular Tom Dick and Harry Mountain trail inside the new wilderness, for example, more than a mile to the south and 1,500 feet above the Laurel Hill Grade. How much more noise is acceptable? How will hikers destined for these trails safely use roadside trailheads to access wilderness areas?

Nearby Camp Creek should be a pristine mountain stream, but instead carries trash and tires from the Mount Hood Highway. While it is protected by wilderness now, how will storm water runoff from an even wider highway be mitigated to avoid further degradation? How will existing pollution impacts be addressed?

The answers to these questions were not considered when this new round of “widening for safety” projects were proposed, but should be addressed before projects of this scale move to construction.

This view west along the Laurel Hill Grade shows the proximity of the new Mirror Lake wilderness additions to the highway project area.

This view east along the Laurel Hill Grade, toward Mount Hood, shows the proximity of the new wilderness boundary to the project area.

In the long term, the solution to balancing highway travel needs with protection of the natural resources and local communities along the Mount Hood corridor needs a more visionary plan to better guide ODOT decisions. Such a plan could establish an alternative vision for the Mount Hood Highway that truly stands the test of time, where the highway, itself, becomes a physical asset treasured by those who live and recreate on the mountain. This should be the core principle of the new vision.

The very complexities and competing demands of the Mount Hood corridor make it a perfect pilot for such a plan — one that would help forge a new framework for managing the highway in a sustainable way that protects both community and environmental resources.

There is also room for optimism that ODOT can achieve a more visionary direction for the corridor. The agency is showing increasing sensitivity to the way in which transportation projects affect their surroundings, as evidenced by in recent projects in the Columbia Gorge and even on Mount Hood.

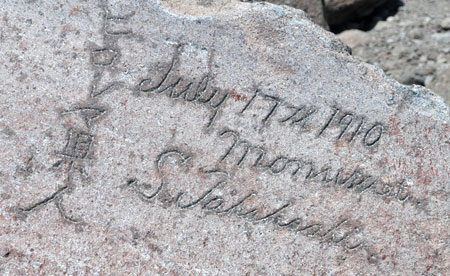

To underscore this point, I chose the logo at the top of this article because it shows a re-emerging side of ODOT that understands both the historic legacy and the need for a new vision for the Mount Hood Highway that keeps the road scenic and special. After all, Oregon’s highway tradition that includes the legacy of the Historic Columbia River Highway, the Oregon Coast Highway and the amazing state park and wayside system was largely developed as an extension of our early highways. ODOT can do this simply be reclaiming what is already the agency’s pioneering legacy..

The Laurel Hill Grade on Highway 26 as viewed from a popular trail in the new Mirror Lake additions to the Salmon Huckleberry Wilderness.

The missing piece is direction from the Oregon Transportation Commission (OTC) to develop a new vision that governs how the highway is managed, and establishes desired community and environmental outcomes by which highway decisions are measured. But until a new vision for the Mount Hood Highway is in place, it makes sense to slow down the current slate of costly projects that threaten to permanently scar the landscape, and take the necessary time to develop a better plan.

If you care about the Mount Hood Highway, you should make your thoughts known on both points, and the sooner the better. The process used by ODOT to make these decisions is difficult for citizens to understand and track, especially online. So, the easiest option for weighing in is to simply send your comments in the form of an e-mail to all three tiers in the decision-making structure, using the contact information that follows.

Comments to ODOT are due by January 31, but you also can comment to the Clackamas County Commission and OTC at the same time. Contact information can be found on these links:

ODOT Region 1

(Select one of the Region 1 coordinators listed)

Clackamas County Commission

Oregon Transportation Commission (OTC)

When describing the projects, you should use the “key numbers” shown in the first map, above, as well as the project names. Simply state your concerns in your own words, but consider these critical points:

- The proposed Mount Hood Highway widening projects should be delayed until less-expensive, less irreversible solutions can be explored;

- The Mount Hood Highway needs a new vision and a better plan

Remember, these are your tax dollars being spent and your public lands at stake. You have a right to be heard, and for your voice to have an impact. With any luck, these projects can be delayed, and more enlightened approaches explored for managing our highway.