The recently collapsed cliff wall along the Collawash River

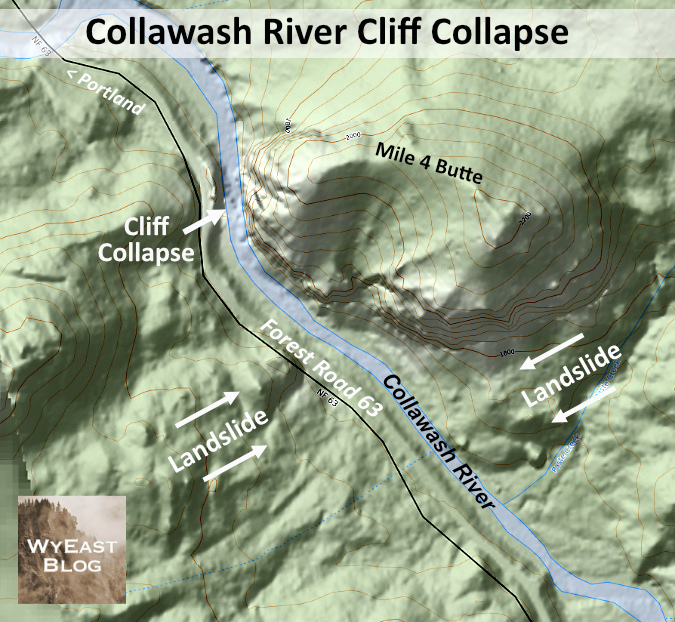

We’re experiencing a bit of a geologic moment in WyEast Country, of late. A series of major cliff collapses in recent years along well-known streams has given us a unique opportunity to see the raw forces of nature at work, shaping the landscape in real time, and also to witness nature rebounding after these violent events. Most of these recent collapses have been along streams in the Columbia River Gorge, but sometime over the past two years, the Collawash River joined the trend.

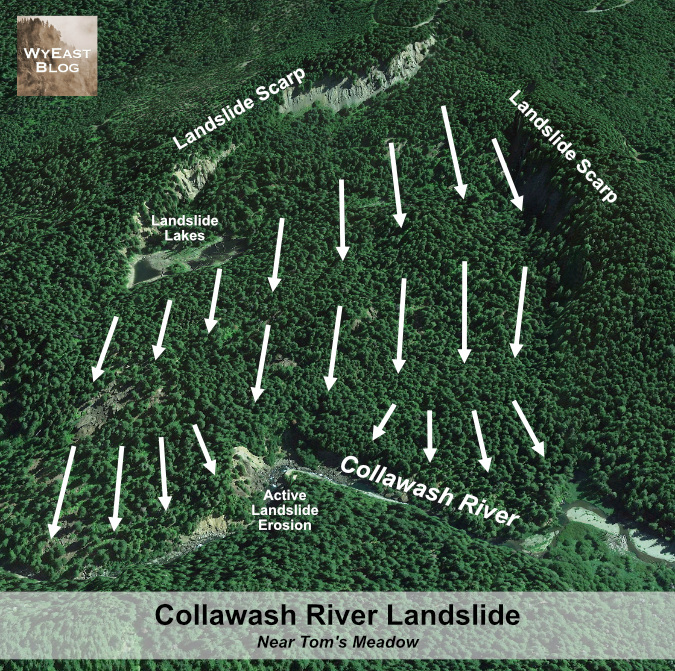

The Collawash River is special. Even in a region known for pristine, spectacular rivers, the Collawash stands apart. That’s in large part due to its unique geology. The Collawash River originates in the remote, rugged Bull of the Woods Wilderness and tumbles through a deep, forested canyon, made perpetually unstable by ancient landslides that are literally pulling the steep mountain slopes on both sides toward the stream.

Massive landslides create a continually changing landscape along the rugged Collawash River

The result is very active landscape along the Collawash, with hundreds of massive boulders marking past landslide events scattered along its course. The ongoing landslides, combined with recent forest fires in the Bull of the Woods Wilderness have also created epic logjams where thousands of trees dropped into the river have accumulated behind these boulders in huge piles.

The erosive action of the Collawash River against the force of these landslides has the effect of a conveyor belt. During high water, the river periodically removes debris from the actively eroding toe of the slides, which in turn, triggers more sliding. This cycle has been playing out for millennia on the Collawash, gradually carrying material from the slides downstream into the Clackamas River, then beyond, leaving only large boulders behind. In time, even the largest of these boulders eventually give way to the elements, and are carried away by the river in pieces.

The dramatic, evolving scenery along the Collawash River is shaped by massive, collding landslides pushing into the river canyon from two sides

One of the many landslides feeding into the Collawash River

[click here for a large version]

Along the way, these landslides also push the Collawash River against solid rock walls along its steep course, allowing the river to gradually cut away at these, as well. Like the erosive process described in this recent article, a solid rock wall that has been persistently undercut by the river eventually collapses, adding still more boulders and loose debris to the river.

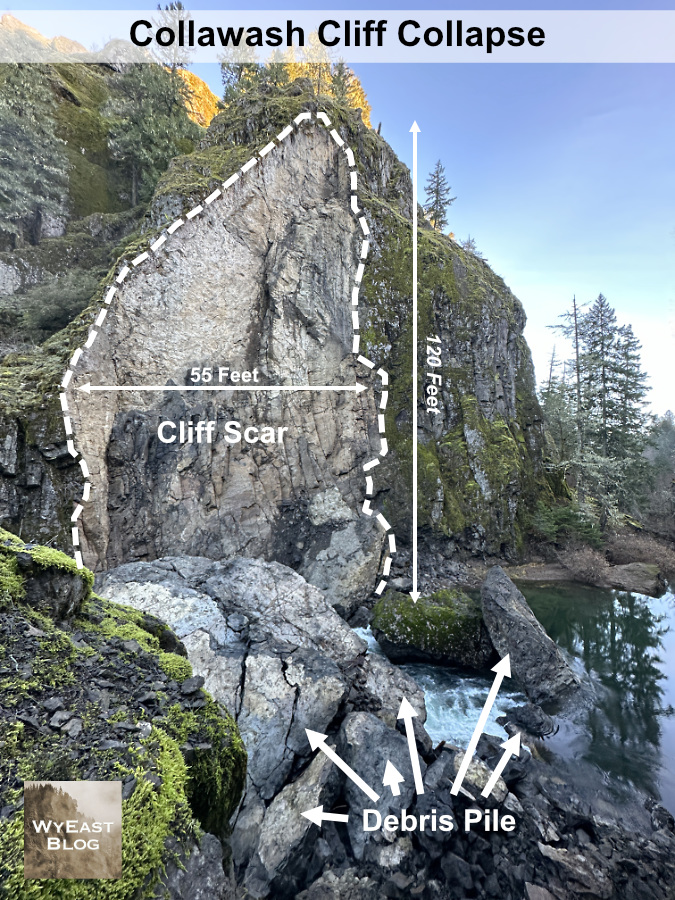

I unexpectedly came across just such an event this year along the Collawash River. The first clue was an eerie slackwater (shown below), with streamside Red Alder inundated under several feet of perfectly still, turquoise water. Just downstream was the answer to this strange anomaly. A massive rock slab had split from a tall cliff along the east bank of the river, crashing into the stream and creating a debris dam that formed a temporary lake on the Collawash.

The eerie, still pool in the Collawash impounded by the recent debris pile

The new debris pile in the foreground and the impounded, temporary lake on the Collawash

The river has since breached the debris pile and is now beginning to carry away fine debris. Note the inundated Red Alder trees in the background

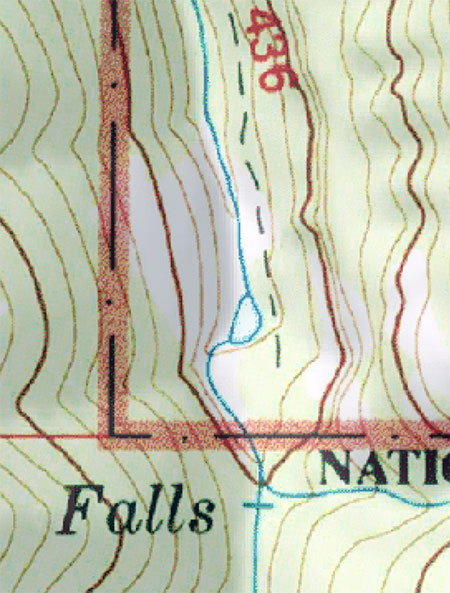

Based on available air photos, the collapse occurred sometime between July 2021 and August 2023 — the 2021 image shows the free-flowing river and the 2023 version clearly shows debris the cliff collapse. While these events can occur at any time of year, those we have seen in recent years have mostly happened during the wet winter months, when the forces of erosion are at their peak.

Based at the state of the debris pile, I would guess that this cliff came down sometime in the winter 2021-22, roughly two years ago. Why this guess? Because with events like this, the debris pile is usually loose enough for the stream to initially flow under it – like a sieve – until the pile settles and when fine material carried in the stream begins to plug small gaps in the settling pile. The other clue is the lack of fine material on top of the pile – the Collawash has clearly had some time to scour the pile of small debris during at least one season of high water.

(Update: per Ian’s comment, below, the Forest Service estimates the collapse to have occurred in February 2023 — a full year later than my guess! They also reported that at that time, the entire river was flowing through the debris and had not yet overtopped it, where today a significant amount of the flow is overtopping the debris. The Collowash is making quick work of this blockage!)

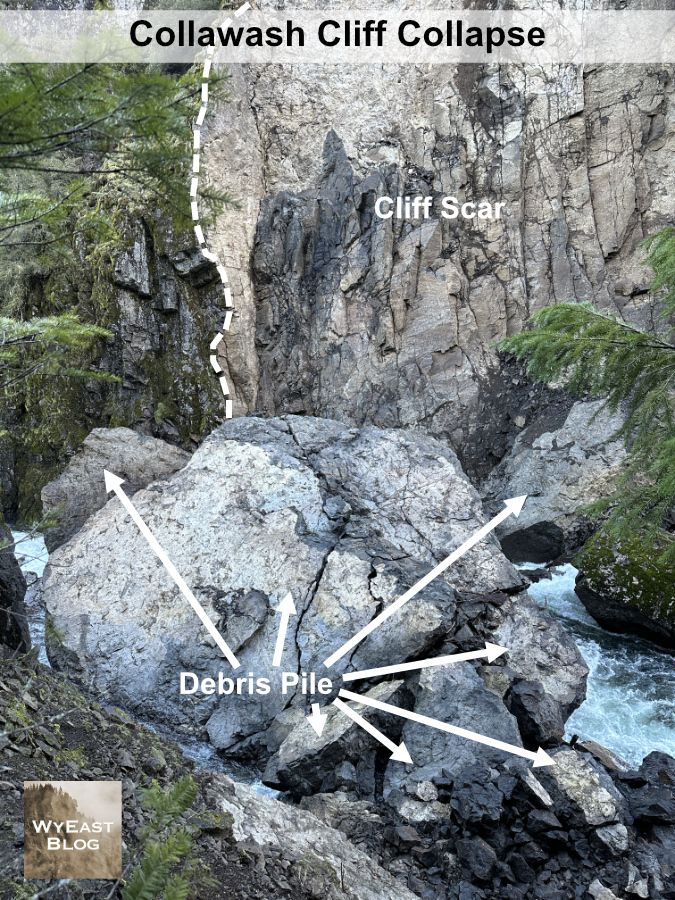

Though a portion of the river’s flow is now cresting the debris pile, much of the flow is still flowing through the loose debris

As with other cliff collapses, several very large pieces of intact cliff survived the fall, but these are already beginning to buckle from their own weight. As the stream continues to churn away at the smaller debris in the pile, the huge boulders sitting on top face enormous stress when the underlying debris beneath them shifts. An especially impressive, house-sized slab that is the largest among the boulders to survive the collapse (below) is already showing large stress cracks. It, too, will eventually break apart as the debris pile continues to shift and erode.

The largest of the intact cliff sections is this behemoth, roughly the size of a small house. Stress cracks are already forming as gravity and the shifting, eroding debris flow beneath the boulder continues to move

Downstream from the debris pile the Collawash River roars through a new Class 5 rapid created by the debris (below). The erosive energy of this steep, newly-formed rapid is immense. Over time it will erode the debris pile from below, continually pulling material from the collapse downstream and allowing the river to cut more deeply into the remaining pile.

New Class V rapids formed below the debris pile where the Collawash is now much steeper than before

Looking downstream from the collapse section, giant boulders in the distance (now moss-covered) from previous collapses reveal the most recent event as just another in a perpetual process of river erosion here

The erosive energy now concentrated in the new rapids just below the debris pile is hydro-physics in action. The panoramic view of the collapse (below) tells the story: the temporary lake on the right hides a series of pools and rapids that existed upstream before the slide, and this energy has now been displaced to the new rapids in the downstream section, just below the slide.

Panoramic view of the cliff collapse showing the impounded lake (right) upstream and the new rapids (left) downstream created by the debris pile at center

[click here for a large version]

This amount concentrated energy of focused on the lower end of the new, unconsolidated debris pile means the river will quickly win the battle of rock versus water that is on full display here. Eventually, this will become what kayakers call a “boulder garden”, eventually draining the temporary lake and leaving only a few of the largest boulders in place to mark the site of cliff collapse. This is only the latest of many such events at this narrow bend in the Collawash River, and it won’t be the last.

The following schematics show the newly exposed cliff scar and the debris left by the cliff collapse in more detail:

The collapse created a 120-foot vertical scar in the cliff

The debris pile from the collapse is dominated by this massive 25-foot wide boulder

In researching this article, I stumbled across an image captured by outdoor writer Zach Urness in the summer of 2019 at the popular swimming hole just below these cliffs. To my amazement, you can plainly see that a prominent crack had formed in the cliff face, and matches the outline of the eventual collapse! I’ve marked it with a series of arrows in the photo below.

View of the Collawash River cliff before the collapse with arrows marking the obvious crack that was forming (photo: Zach Urness)

Closer view of the Collawash River cliff before the collapse with arrows marking the crack that would eventually lead to the collapse (photo: Zach Urness)

Zach’s photo also shows how this spot in the stream was already littered with large boulders from prior collapses before the collapse. There’s no way of knowing when these earlier events occurred, but we do know from witnessing the latest collapses here and elsewhere in WyEast Country that they are more common – and constant – than we once thought.

The lack of photos or reporting on the collapse has a silver lining: Zach’s photo was taken from just above the Little Fan Creek picnic area, located at the confluence of the main Collawash and Hot Springs Fork. This area is especially popular with families in the summer months, with crowds of people floating and swimming the many pools in the river, and where a summer event might have had deadly consequences.

How to see it for yourself…

The graceful Collawash River Bridge was constructed in 1957 as part of logging heyday in the upper Clackamas River watershed

The recent cliff collapse on the Collawash River is easy to visit if you’re looking for a weekend drive. The winter off-season is the best time, too, as the Clackamas River corridor is popular and often busy during the spring and summer months. To reach the site, head up the Clackamas River Highway (OR 224) for 26 miles east of the town of Estacada to the Ripplebrook ranger station and campground, Here OR 224 becomes Forest Road 46. Continue for another 3.5 miles on FR 46 to an obvious (but usually unsigned) junction with the paved Collawash River Road (Forest Road 63).

Turn right onto FR 63, and be sure to take your time along this stretch. Here, the road hugs the Collawash River through an exceptionally scenic and geologically interesting areas. You will immediately cross a beautiful arched bridge over the Collawash as you enter the river’s narrow lower canyon on FR 63. Views of dramatic cliffs, river rapids and impressive old growth trees are at every turn, with frequent pullouts for stopping.

Autumn scene along the Collawash River Road

At about the 4-mile mark you will reach another junction, where paved Forest Road 70 heads right to well-known Bagby Hot Springs, located on the Hot Springs Fork of the Collawash River. Stay straight on FR 63 from this junction and immediately cross the Hot Springs Fork on second bridge. The recent cliff collapse is just upstream from here, so watch for an obvious boulder perched on a pile of moss-covered rock on the east side of the road (shown below). This is where the collapse occurred.

There’s room for shoulder parking next to the perched rock, and the best view is from the upstream side of the big boulder, on top of the rock pile. Use care scrambling up the rock pile – there’s a steep drop on the opposite side!

While it looks poised to roll onto my car, this boulder is from an earlier cliff collapse that occurred well before the Collawash River Road was built in the 1950s. The best viewpoint of the latest collapse is from the top of this rock pile, next to the big boulder

Though the Collawash River was mostly spared by the Riverside Fire that swept across 138,000 acres in the Clackamas River watershed in 2020, the Clackamas River Highway route to the Collawash River travels through much of the burn. While this might sound a bit bleak for a scenic drive, it’s a great opportunity to fully appreciate the scope of the burn and watch the beginnings of the post-fire forest recovery here.

The Riverside Fire was the third and largest of three human-caused fires to sweep through the Clackamas River canyon over the past two decades. While fires are a natural and necessary element to forest health in the Pacific Northwest, it’s also true that human-caused fires are burning the Clackamas River basin (and many other forests in the Pacific Northwest) at an unsustainable pace.

The human-caused Riverside Fire roared across the Clackamas River area in September 2020 burning 138,000 homes and dozens of structures in its path

Human-caused fires are also killing old-growth riparian trees that have survived centuries of wildfires. Why? In part because of the intensity of these recent burns as a result of decades of fire suppression, but also because riparian areas were often be spared in the past by natural, lightning-sparked fires that typically began on exposed, drought-stressed ridgetop forests – not in moist rainforest canyons, where all three of the human-caused fires on the Clackamas started.

The Forest Service is still gradually reopening the many campgrounds and picnic areas along the Clackamas River that were affected by the burn, so you are likely to encounter logging operations where trees deemed “hazardous” are being removed by contract crews. These projects are well-signed and easy to avoid if you’re following the main route.

The Forest Service is still logging fire-killed or weakened trees like these along major forest roads in the Clackamas area as “hazard trees”

For a longer tour, you can continue further upstream along the Clackamas River Highway from the Coillawash River Road junction. The highway hugs the Clackamas River for another eight scenic miles, with pullouts along the way to appreciate the views. This section of the highway passes Austin Hot Springs, an interesting area, but also a private inholding within the national forest, and not open to the public.

Above the Collawash River confluence, the main Clackamas River is unburned and a reminder of what the lower canyon looked like before the 2020 Riverside Fire

As you explore the area, you may begin see each vertical cliff and outcrop with new eyes as – perhaps – the next real-time geologic event! Chances are slim that any of us will witness such an event, but seeing the aftermath of the Collawash River collapse gives a new appreciation for the constant natural processes that continue to shape the scenery around us.

Enjoy!

_______________

Tom Kloster | January 2024