Columbia Prickly Pear colony thriving on the morning side of WyEast

I am a cactus fanatic. As a seven-year-old, I had a row of them in my bedroom window. They were little collectibles in 2-inch pots that you could buy at Fred Meyer for 49 cents. On my first road trip to the Desert Southwest in 1984 I couldn’t get enough of them. That was the first of many trips, often timed to capture cactus in bloom – to me, the ultimate in wildflower beauty.

Cactus are the rattlesnakes of the desert wildflower community. They combine exquisite beauty with remarkable evolution for a strong self-defense. Did you know that cactus spines are really their leaves, modified for both defense and shade? Or that the pad on a prickly pear cactus is really a thickened stem that carries out photosynthesis in the absence of green leaves? They have evolved to a point that seems downright alien to most other flowering plants.

Brittle Prickly Pear colony growing in the Painted Hills Unit, John Day Fossil Beds National Monument

A few years ago, I came across my first prickly pear cactus in Oregon. It was one of our native species, Brittle Prickly Pear, growing in the John Day National Monument at the Painted Hills Unit. I revisited that patch a couple of times over the years, and finally saw it in bloom – another highlight!

Since then, I have found dozens of Brittle Prickly Pear colonies all around the Painted Hills and adjacent Sutton Mountain areas, often covered with blossoms in late May and early June. Even in bloom, these plants are easy to miss in their native desert habitat. Their compact pads are rounded, about the size and shape of your thumb, and covered in grey spines that also act as camouflage against the desert floor. A mature plant has 20 to 30 pads growing in a low mat that is usually less than 6 inches tall.

Brittle Prickly Pear blossoms at Sutton Mountain, near the Painted Hills

Brittle Prickly Pear bear fruit after blooming and can spread by seed, mostly by birds who navigate the cactus spines to feed on the soft inner part of the fruit. Called “tunas”, their fruit is sweet, putting the “pear” in their common name. Like other Prickly Pear species, they have long been used by indigenous people as a food source and medicinally. Fruit from larger Prickly Pear species is still used to make jams and other foods in Native American and Mexican culture.

Their heavy coat of spines and the ability of pads to freely break away is how Brittle Prickly Pear most commonly reproduce. When kicked loose by deer hoof or hiking boot, a stray pad is given a chance to take root and start a new patch in a local colony of cactus. This is how these “brittle” cousins in the Prickly Pear family earned their common name.

Our northern cactus may be diminutive in stature, but they are built small for a reason. Unlike their much larger relatives in the Sonoran Desert, ours endure bitter winter cold and months of winter storms that would flatten the larger cactus you might see in the Sonoran deserts of Arizona or New Mexico.

Ahab and Moby Cactus…

Given my cactus obsession, I had it in my mind to someday see another of our local cactus: the Columbia Prickly Pear, a species that only grows in low-elevation deserts of the Columbia River and Snake River basins. It became my white whale, and I was determined to see Moby Cactus!

There is still some debate as to whether these are a separate species or a hybrid of our Brittle Prickly Pear and Plains Prickly Pear. The latter is a much more common species that grows across much of the West. Botanists have yet to fully agree on this, so for now Columbia Prickly Pear is called Opuntia Columbiana X Griffiths. The last part of the Latin name comes from botanist David Griffiths, who first documented the species for Western science in the 1920s.

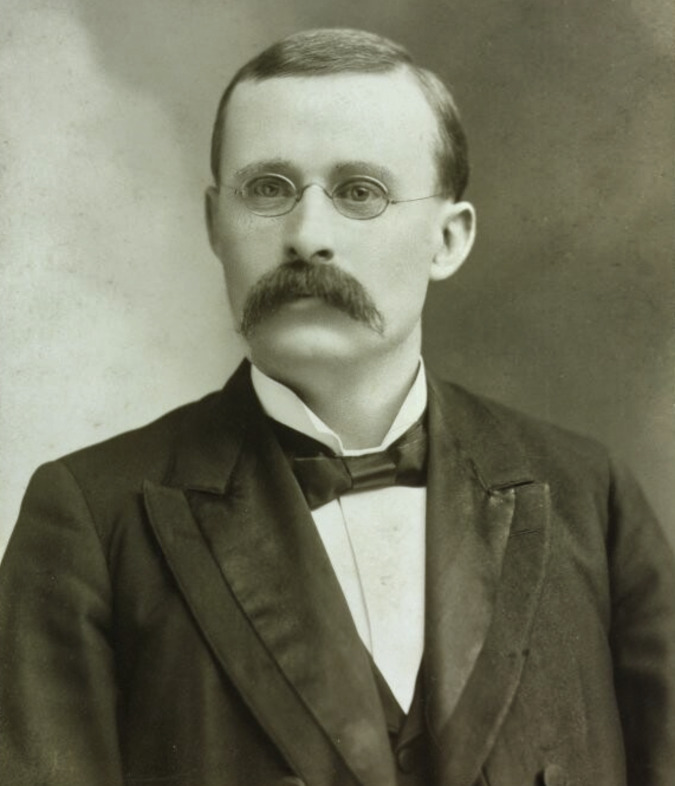

Pioneering western botanist David Griffiths in 1903 (Università di Padova)

Griffiths was from a Welsh family that immigrated to South Dakota in 1870, when he was just three years old. He earned a doctorate in botany from Columbia University in 1900, and went on to distinguished career as a groundbreaking scientist working for the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). There, he spent the first part of the 20th century traveling across the American West documenting plants and photographing the range conditions of the Great Basin at a time when the impacts of fencing and heavy grazing on the desert ecosystem were first beginning to appear.

His work was seminal in helping the USDA improve range management practices on our public lands across the West. When Griffiths died in 1935, he donated his botanical records and collection of glass-negative photographs to The Smithsonian National Museum, along with hundreds of Opuntia specimen that he had collected over his career. The Smithsonian describes his archives in bulk terms — 43 cubic feet, to be exact! Griffiths’ field research legacy is still cited by today’s botanists and rangeland scientists, and his name lives on in our local Columbia Prickly Pear.

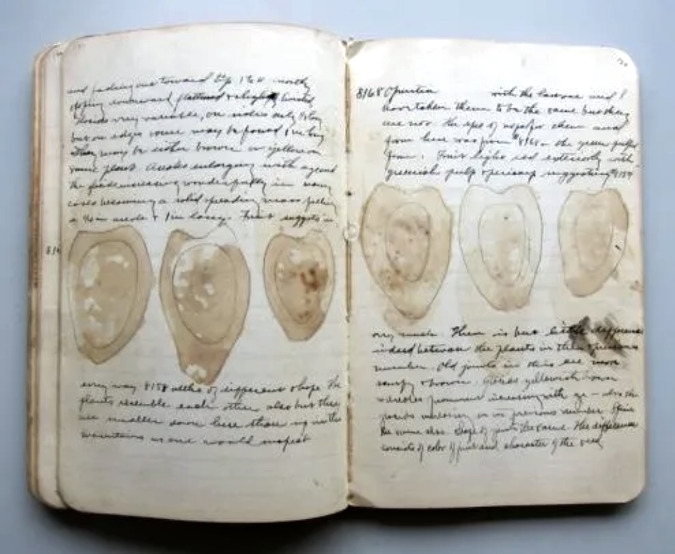

One of David Griffiths dozens of field notebooks. These pages describe the inside of Prickly Pear fruit. He is believed to have sliced fruit open and simply pressed them against the page to create these images (Smithsonian Museum)

Though David Griffiths has come to be remembered mainly for his passion for the Opuntia family of cactus, his interest in these tough, versatile survivors initially came from a belief that they could somehow be a livestock feed source on the open range. As odd as this sounds, the pads and fruit are already important for deer, antelope, squirrels and other wildlife who either consume the pads whole or work around the spines to get to the flesh. Other wildlife are more opportune, and consume Prickly Pear after range fires have swept through, searing their spines off. This is precisely how indigenous people prepared the nutrient-rich pads and fruit as a first food for millennia, though the spines were also used for sewing, fish hooks and other purposes.

Not too long before Griffiths first cataloged Prickly Pear cactus, white immigrants to the American West discovered them, as well – and not in a good way. Journals from the Oregon Trail describe the misery of migrants stepping through prickly pear as they crossed the western plains in worn out shoes, as most who traveled the Oregon Trail walked beside their wagons for much of the journey.

Our native cactus are easy to miss in the wild. There are at least five patches of Columbia Prickly Pear in this colony along the Columbia River – marked by arrows. In spring, they are especially well-hidden in new, green grass

Having skewered myself a few times with their spines, I can attest to the lingering soreness that comes with getting poked by a Prickly Pear. I suspect native peoples were more adept at navigating them — even nurturing them, perhaps, since they were valued for their food and cultural value. The photo above gives a sense of how well-camouflaged our Columbia Prickly Pear are in the desert grasslands and sagebrush country of the eastern Columbia River Gorge. The arrows point to several patches of cactus in this colony, each no more than 10 inches tall, yet wide enough to snare an inattentive foot!

The 2025 cactus hunt…

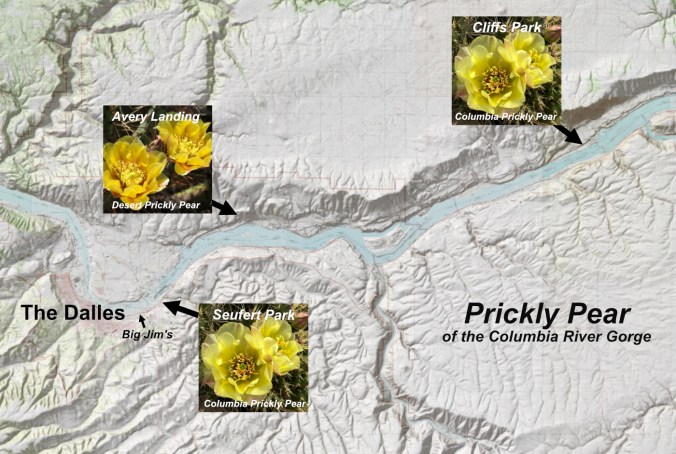

Local wildflower buffs and botanists had already done the hard work and locating Columbia Prickly Pear in the east Columbia River Gorge, making my mission much simpler. There were at least three well-documented colonies, and knowing this, I made 2025 the year that I would see them for the first time – and perhaps even photograph them in bloom.

I initially set out over the winter to simply locate the known colonies from fairly general maps posted online. The first colony was located across the river from the Dallas Dam in a most unlikely spot, surrounded by buzzing transmission lines from the dam and traffic noise from interstate 84. However, this colony was also safely within the confines Seufert Park, a Corps of Engineers site adjacent to The Dallas Dam visitor center.

Columbia Prickly Pear thriving just upstream from the Columbia River Bridge in The Dalles. While these can be tough to spot in spring and summer, they stand out strikingly in winter with their spines capturing the low-angle sun and surrounding grasses dormant and flattened by the winter elements

A short trail hike and a bit of cross country exploring took me straight to a colony of about a dozen cactus patches. They looked much like their Brittle Prickly Pear cousins, though their pads were more flattened and slightly larger. It was a thrill to see them growing right here in WyEast country, with the Columbia River spreading out below and Mount Hood shining on the horizon. I’d found my whale!

The next stop took me across the river to Avery Landing, another Corps of Engineers recreation site, just upstream from Columbia Hills State Park and Horsethief Butte. Expecting to find a similar colony here, I wasn’t prepared to find a much larger group of much larger plants! The pads on these plants were as much as 6 inches across, and flat like the Prickly Pear cactus I had seen in the Desert Southwest. These plants stood as much as 2 feet high, and were growing on a high, rocky bench with a beautiful backdrop of the Columbia River and Mount Hood, beyond.

Prickly Pear cactus at Avery Landing grow on a rocky bench, a few hundred feet above the park and Columbia River. These are much larger plants than what I saw at Seifert Park.. why?

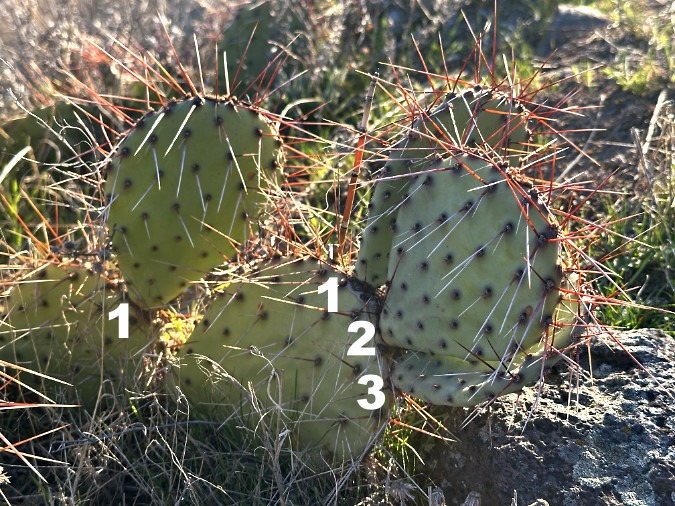

With the summer grasses and wildflowers dormant, the structure of Prickly Pear on these very large plants was easier to understand. New pads – the modified stems – grow from nodes on the edge of older pads, with typically 1-3 new pads emerging each spring, as shown below.

How Prickly Pear grow, typically with one to three new pads forming on the margins of an older pad

Over time, this growth habit eventually tips the plants over from the successive weight of each new pad, making them seem to be growing horizontally. When pads touch the ground, they can easily take root, forming a new plant and helping further spread the patch from the original, parent plant. In the image below, each successive pad marks at least one year of growth, as new pads don’t always form on old pads. Thus, this stem of four successive pads is at least four years old, with the newest pad nearly touching ground where it might take root.

This chain of Prickly Pear pads originally stood upright, but has gradually tipped and sprawled with the weight of each successive new pad. Eventually, these pads can root and form new plants if they touch the ground

Though not as common, some older pads that support many newer pads eventually become woody stems to support the load. The image below shows how these stems gradually change from green, energy-producing pads to brown, more conventional stems. The pad near the woody portion of the stem is undergoing this transition, having lost the chlorophyll from the lower portion of the pad.

This Prickly Pear at Avery Landing has developed a woody stem from what was once a green pad in order to hold up the heavy load of successive pads that have emerged

For a cactus fanatic, exploring the colony at Avery Landing was a heady experience! But I had one more colony to visit in completing my initial tour of Prickly Pear in the Gorge.

The final winter stop took me Cliffs Park, yet another Corps of Engineers site, located on the Washington side of the river at John Day Dam. This is a familiar place to me, as I have photographed the beautiful river scenes and ancient gravel beaches that line the Columbia here many times. Using online maps, I found just two small plants that were about the same size in stature as those in Seaford Park, but in much smaller patches. It was a disappointing stop, especially compared to the large colony of very large Prickly Pear at Avery landing. Did I miss something?

Like the Columbia Prickly Pear at Seifert Park, the small colony at Cliffs Park grows in the shadow of one of the massive Columbia River Dams. The John Day Dam rises above this cactus patch

However, as I was photographing the small colony at Cliffs Park, I noticed new buds emerging from some of the pads (below). Were these flower buds or new stems? Surprisingly, some of the buds were also located on the flat side of the pad in addition to the edges. This was quite different from what I had seen at Avery Landing. I was now determined to come back and do a more thorough search in this area and document the growth of these buds in spring.

The arrows point to new buds emerging from this Columbia Prickly Pear at Cliffs Park in early March. Are these flower buds or new pads forming?

As spring approached, I made several more visits to the impressive colony at Avery Landing, and was especially excited in early May to find the plants loaded with flower buds (below). These buds developed very quickly, over just a couple weeks.

Hundreds of flower buds were nearly ready to open at the Avery Landing Prickly Pear colony in mid-May

When the Avery landing colony finally began blooming in late May, I was there with my camera to capture it all, including a photo with the trifecta of cactus blossoms, Mount Hood, and the Columbia River that I had been hoping to capture (second photo, below).

The first Prickly Pear blossoms to open in the Avery Landing colony in late May

Trifecta! Blooming Prickly Pear, the Columbia River and Mount Hood a few days after Memorial Day in late May

However, this is where the story takes an unexpected turn. When I took these photos, I thought the Prickly Pear colony at Avery Park to simply be a more vigorous, over-achieving version of the same Columbia Prickly Pear growing across the river, at Seufert Park. Perhaps their much larger size was simply a reflection their habitat? Where the Seufert Park and Cliffs Park colonies were growing on arid, thin soils atop basalt outcrops, the Avery Park colony grows in deep, sloping sand and gravel deposits left behind by the Missoula floods. Perhaps these soils simply offer more moisture and nutrients than are available to their smaller neighbors across the river?

Only after sharing photos of the Avery Landing colony in an online wildflower community, did I learn that the Avery Landing cactus were not our native Columbia Prickly Pear at all! Instead, these are Desert Prickly Pear, an introduced species known as Opuntia Phaeacantha that grow across much of the desert southwest and into the southern Great Basin. Fact is, their true identity wasn’t completely surprising to me, as the growth habits and size of the two species are so different. But it was disappointing.

Desert Prickly Pear is the true identity of the introduced cactus species growing at Avery Landing

It’s hard to say whether these Desert Prickly Pear were planted here intentionally or arrived here accidentally, but they are thriving now. They have formed an extensive colony of at least 25 separate groups that span a 100-yard long bench above the Columbia River. Their size and the extent of the colony suggests they have been here for some time – likely decades or longer – so they are clearly here to stay.

It’s hard to know exactly how the Desert Prickly Pear cactus have been spreading in the Avery Park colony, but because they are mostly clustered along an abandoned road grade (as highlighted on the map below), their spread here could simply be from human or wildlife activity kicking pads loose to root and begin a new patch.

The Desert Prickly Pear colony at Avery Landing grows on a gravel bench that splits off the access road to the park. The separate groups that make up the colony fall within the highlighted area on this map

However, when I visited the colony again in mid-June, the blossoms had mostly faded and the colony was busy forming hundreds of fruit – tunas – that I think might be the primary explanation for the size of the colony. That’s because there is plenty of wildlife sign here, including a very active colony of California ground squirrels living in the basalt outcrops that border the bench. I suspect they are among the wildlife species feeding on the fairly large tunas and thereby spreading their seeds.

Desert Prickly Pear blossoms have dried up on this plant by early June. They will soon drop off as the fruit beneath ripens

Desert Prickly Pear fruit after blossoms have fallen off in mid-June. They will eventually turn to a reddish-purple color as they ripen

As disappointing as the revelation of their true identity was, the colony of Desert Prickly Pear at Avery Landing is nonetheless a spectacular sight. We may be seeing our future here, too, as climate change spurs plant species from across the spectrum to migrate northward as our Pacific Northwest climate becomes warmer. Already, this colony of Desert Prickly Pear is proving the eastern Columbia River Gorge to be an ideal habitat for a species whose native range is nearly 1,000 miles to the south.

Because I had spent much of the annual bloom window in May at Avery Landing, focused on what I thought were Columbia Prickly Pear cactus, I hurriedly doubled back to the colony at Seufert Park hoping to catch the colony there in bloom. No such luck. By the time I returned there in early June, they were completely bloomed out. Still, I was encouraged to see so many dried blossoms on these plants. I knew I would have another chance to photograph them next year, and a fair estimate of their bloom window in late May.

Columbia Prickly Pear at Seufert Park, with dried blossoms just days after the annual bloom cycle. Blossoms here were much less prolific than on the Desert Prickly Pear at Avery landing. The arrows mark just two blossoms on this large patch

Dried Columbia Prickly Pear blossoms at Seufert Park. The fruit (or “tunas”) beneath the spent blossoms were developing quickly here, already turning to their characteristic ripened hue of deep reddish-purple

Finding only dried blossoms at Seufert Park, I headed east on a very hot June day to revisit the tiny group of Columbia Prickly Pear I had seen at Cliffs Park by the John Day Dam. Perhaps these might still have a few blooms? This time, I ignored the online documentation on the colony and explored the basalt outcrop they grow on more broadly. Sure enough, just 50 yards from the two small plants I had seen on my first visit, I came across at least two dozen well-developed patches in a colony that surpassed Seufert Park. Eureka!

However, the desert grassland had completely browned out for the summer at Cliffs Park, and the cactus were completely bloomed out, too. Still, I was excited to find so many plants here and spent much time that day exploring and photographing them.

Part of the surprising Columbia Prickly Pear colony at Cliffs Park (John Day Dam in the distance). Each arrow marks a separate patch

Then, just as I was getting ready to leave the Cliffs Park colony, I came across one last patch of Columbia, Prickly Pear with a single blossom still hanging on. Fortunately, nobody was around to hear when I let out a whoop! I set up my camera and documented that lonely cactus blossom like no flower has ever been photographed. Ahab had finallyfound his whale!

A straggler! One last Columbia Prickly Pear blossoms (center right) was hanging on for my visit to Cliffs Park in early June. And yes, a trifecta – snowy WyEast and the Columbia River are in the distance

Last of the Columbia Prickly Pear blooming at Cliffs Park in early June

Though I missed most of the spring cactus bloom at Cliffs Park, there was plenty of evidence that it had been a good year, with ripening fruit throughout the colony. And while the blooms had been fairly scattered across the colony, there were also plenty of new pads that had developed over the spring, with new, soft spines that were still hardening into new armor.

Fruit forming beneath dried blossoms on Columbia Prickly Pear at Cliffs Park

The Columbia Prickly Pear colony at Cliffs Park is healthy, with several blooms and many new pads emerging this spring. In this view, four new pads have formed. They can be identified by their short spines that have yet to fully mature

It was already hot and dry at the Cliffs Park colony by early June, so these plants won’t get much moisture until well into September, putting their unique water storage ability into use, once again.

Columbia Prickly Pear at Cliffs Park ready for the summer dry season. This plant has added just one new pad this season (lower right), illustrating how slowly these plants grow in their harsh environment

While the rest of the desert goes dormant until the rains return, these unique plants will remain green and producing food for their root systems throughout the summer and their spines will help protect them when most other forage is long dried up in the desert landscape. This is the genius of their evolution.

They seem to like it on the rocks…

Learning that the Avery Landing cactus colony was an introduced species and not the native Columbia Prickly Pear we have at Seufert Park and Cliffs Park helped me understand the preferred habitats for both species, as they are quite different.

The Desert Prickly Pear at Avery Landing is happy on flat or steep slopes, provided that it can grow in loose, sandy or gravely soils. The Gorge has plenty of this with deep Missoula flood deposits lining the river on both sides, sometimes hundreds of feet deep.

Desert Prickly Pear at Avery Landing seem to prefer the loose benches of Missoula Flood sand and gravel that were left here by ice age floods

Desert Prickly Pear seem highly adaptable, some growing in flat areas and hollows, while others thrive in steep ravines and slopes

Sandy soils seem to be key to the flourishing Desert Prickly Pear colony at Avery Landing

Colorful Missoula Flood gravels are mixed with the sandy soils at Avery Landing, another ingredient the Desert Prickly Pear seem to favor

In contrast, the Columbia Prickly Pear colonies at Seufert Park and Cliffs Park are growing in loose scrabble directly on top of exposed basalt outcrops where the Missoula Floods scoured the bedrock. These are harsh places that seemed impossible for a plant to survive, yet our native Columbia Prickly Pear seems to prefer them.

Columbia Prickly Pear at Seufert Park grow in thin, gravelly soils on a basalt bench above river. A second cactus patch in this view is shown with an arrow

This Columbia Prickly Pear at Cliffs Park is growing from a narrow crack in the basalt

This young Columbia Prickly Pear at Cliffs Park has somehow found a toehold on top of a basalt slab

This is especially apparent at Cliffs Park, where the colony is scattered across a low basalt table, despite being surrounded by deep soil deposits of gravel and sand on three sides.

The Cliffs Park colony favors the top of this dry basalt ledge over the deeper soils that surround it, perhaps because there is less competition there from other plants?

The best explanation might be simple competition, as the sandy areas with deeper soils support much more vegetation, including several wildflower species, where the basalt table is mostly limited to grasses, moss and lichen. Where a thin layer of soil has accumulated on the table, the Columbia Prickly Pear seem most at home. Their unique ability to withstand extreme drought also makes them uniquely able to grow under these harsh conditions.

Helping the Columbia Prickly Pear thrive?

While our Columbia Prickly Pear are not common, they are (fortunately) neither rare nor threatened. They’re just quite hard to find. That’s a shame, because they are unique and deserve to be more widely known and appreciated. This article was written in that spirit (including some general directions for finding them, below).

Were Columbia Prickly Pear much more common in the Gorge when Benjamin Gifford took this photo in 1899 at today’s Cliffs Park? I think so…

Why are they so uncommon? My theory as to their present scarcity is simply the wear and tear on the Columbia Gorge since the era of white settlement began nearly 200 years ago. Heavy grazing, first by sheep, then cattle, surely had an impact. Railroad, highway and dam construction followed, and – most recently – windmills. All disrupted our native flora and fauna. Unlike most other wildflowers, cactus are slow growers, and I suspect they are simply more vulnerable to frequent disturbance. This might be another explanation for colonies living atop rocky basalt outcrops where not much else survives.

To help remedy this state of affairs for our Columbia Prickly Pear in a small way, I’ve taken on a project that I thought I’d share here.

The oddly small number of our native cactus in their native landscape inspired me to try propagating them with the intent of starting some new colonies. My (perhaps half-baked) plan is to offer them to public land managers in the Gorge interested in to establishing new Columbia Prickly Pear colonies in a few new spots of similar habitat along the river – of which there are many.

With that goal in mind, I had collected some pads at Avery Landing last winter for propagating before I knew these to be a different species than our native Columbia Prickly Pear. They rooted nicely, but now they will be donated to a garden in Portland – not the Gorge.

Prickly Pear propagate readily, even from the somewhat withered, bedraggled state of these Desert Prickly Pear cuttings in March

By May the Desert Prickly Pear starts had plumped up from their withered state, showing they had quickly grown new roots. Soon, they began pushing out buds for new pads just two months after I planting. Three new buds are numbered here

By early July, the Desert Prickly Pear cuttings were fully rooted and forming new pads

More recently, I collected some pads from our Columbia Prickly Pear. I’m hoping to root them over the summer and offer them to any interested public land managers, especially state parks. Collecting the pads was simple and discreet – as in, I left no trace. The tools involved a pair of kitchen tongs, a paring knife, leather gloves and a paper grocery sack (as I said in my opening, I’m a cactus fanatic, and growing them is in my wheelhouse!). Once harvested, I gave them a few days for the cut to form a callous before planting them in a 50/50 mix of potting soil and perlite.

Columbia Prickly Pear pads collected for propagation in mid-June

Columbia Prickly Pear pads ready for potting in mid-June

The Columbia Prickly Pear nursery in the foreground (smaller pads with yellow-green coloring and white/grey spines) is clearly different in this side-by-side comparison to the much larger Desert Prickly Pear starts (in back, with blue-green pads and red/brown spines)

And then there’s the little cactus shown below. As I was exploring the colony at Cliffs Park, I found this seedling growing on the gravel shoulder of the park road, just a few inches from the asphalt pavement. I had nearly flattened it when I parked on the shoulder! It was clearly doomed there, so thanks to a small trowel I carry my trail car, this little rescue is now growing happily in a pot, waiting to be planted in some permanent location where it might start a new colony.

The little rescued cactus also gave me a good look at their root systems in the wild. They are surprisingly shallow-rooted! It makes sense when you consider their ability to store water in their pads, and their preferred habitat in shallow, rocky soils.

The Cliffs Park rescue cactus gave me my first look at the surprisingly small root system these plants have in the wild

The Cliffs Park rescue cactus potted and growing in his (her?) new home for a while

I don’t have a specific plan for this project beyond propagating a few plants, but my lifelong cactus obsession would not let me do otherwise. I just think that more people should see these amazing plants in places where they likely used to grow in the East Gorge, before white settlement.

Should you propagate these plants? It’s perfectly legal to take cuttings, so if you own property in the East Gorge with the right habitat and are looking to add native species, yes. You would be helping this unique species thrive. Otherwise, simply admiring them in the wild is the best plan. They don’t make for great ornamental cactus for urban settings compared to the many cultivars out there that have been bred for our gardens.

Where you can see them…

If you are interested in seeing cactus growing right here in the Columbia River Gorge, the colonies at Avery Landing and Cliffs Park are very easy to visit. Both bloom from mid-May into early June. Like many cactus species, the blossoms seem to open during the middle of the day and into evening, so afternoons are the best bet for a visit. However, they are fascinating plants to see any time of year, not just during the blooming cycle.

The Columbia River Gorge Prickly Pear tour begins in The Dalles (and ends at Big Jim’s for a milkshake, of course)

[click here for a large, printable map]

While the Avery Landing colony of Desert Prickly Pear are not native, they are beautiful and grow in a spectacular setting. Most of the colony grows along an old road grade that splits off the paved access road to the park. Watch for it heading off to the right just past the winery at the top of the hill. If you cross the railroad tracks, you have gone too far. Here’s a view (below) of the road grade looking back toward the park road and winery – you can park where I did.

Looking east along the old road grade that is home to a large Desert Prickly Pear colony

Part of the Avery Landing colony is on private land, and clearly defined as such with the fence gate. Please respect private property rights.

To see our native Columbia Prickly Pear, you can visit them along the paved access road to Cliffs Park, located on the Washington side of the river at John Day Dam. Follow the road into the park, and pull off just before it turns to gravel. Here’s a wayfinding photo – watch for these signs and pull off just beyond them. The cactus colony is on the low basalt bench just ahead, on the right (north) side of the road.

The Cliffs Park colony is located on the low, rocky bench directly beyond these park signs

Walk slow and carefully to avoid stepping on them – both for your benefit and theirs! And as with any desert hiking, watch your step for rattlesnakes, too. While you’re not likely to see one, they do like to bask in late morning and early afternoon in rocky areas like this.

The towering backdrop to the Cliffs Park colony are the sacred bluffs that I described in this article (you’ll need to scroll down). This is the area where a proposed energy project is being contested by area tribes and many other groups.

If you’d like to learn more about the controversial project from the perspective of the Rock Creek Band of the Yakama Nation, a powerful new documentary called “These Sacred Hills” is currently being screened around our region. https://sacredhillsfilm.com

The sacred hills rise above the Cliffs Park colony of Columbia Prickly Pear

While you are at Cliffs Park, consider traveling a bit further down the gravel road to visit the expansive pebble beach composed of Missoula flood deposits. Mount Hood floats on the horizon, making this one of the most beautiful spots on the Columbia River.

Mount Hood rises above traditional fishing platforms and the vast beaches of Missoula Flood rocks at Cliffs Park

This is a traditional Indian fishing spot, and you will see several fishing platforms here. The park is open to everyone, but please respect the tribal fisheries and the native fisherman who may be working here. I personally choose not to photograph indigenous people fishing, even on public lands.

I did not include Seifert Park on this itinerary for a couple reasons. First, the cactus here are harder to find than those at Avery Landing and Cliffs Park. Also, while it is public land and open to anyone to explore, the park also includes treaty-protected tribal fisheries. If you do go there, please respect the rights and privacy of the tribes.

These rocky outcrops are home to the Seifert Park colony of Columbia Prickly Pear, but they are also protected tribal fisheries. Please be respectful if you explore here

To see our little Columbia Prickly Pear cactus growing in the most unlikely of places gives a sense of the timelessness of nature, despite these colonies being surrounded by transmission towers, the noise of the dam spillways, railroad and highway traffic and the bones of abandoned industries. While the hand of man has not been kind to these areas, the resiliency of nature is truly impressive and inspiring.

_______________

Tom Kloster • July 2025