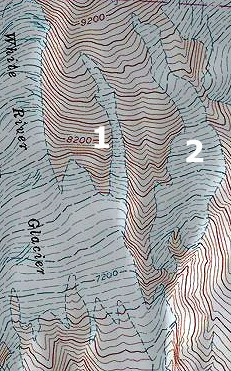

It seems implausible, but climate change may be creating new glaciers on Mount Hood — but not in the usual way that glaciers are created. A close look at the retreating White River Glacier on the sunny south flank of Mount Hood reveals two stranded arms that are now separate glacier. As marked by (1) and (2) on the photo, above, a pair of truncated mini-glaciers have been cut off from the main flow of the White River Glacier by a previously hidden moraine that is now being exposed by the rapidly retreating ice.

Until fairly recently in geologic time, the White River Glacier extended far beyond its current extent, flowing down the rugged canyon shown in the photo for several miles to a terminus far beyond where Highway 35 now crosses the glacial outwash plain. But the glacier is retreating rapidly, destabilizing the canyon and changing its shape as it shrinks.

A closer look at two mini-glaciers on Mount Hood

A closer look at the two mini-glaciers reveals why a glacier is different from a static field of ice. Glaciers flow under their own weight, sending waves of ice sliding downward as more snow is added, above. Huge cracks known as crevasses form at stress points in the river of ice, and these are a defining feature in identifying a glacier. Both of these sheets of ice have crevasses, and thus are moving glaciers.

A look at the topographic map shows how the extent of the White River Glacier has changed as recently as the 1960s, when the map was surveyed. The mini-glacier marked as (1) was clearly an arm of the White River Glacier until very recently, but surprisingly, the second mini-glacier (2) appears to already have separated from the main glacier before the surveys were done — though it is clearly a truncated lobe of the main glacier, as well.

Another defining feature for this pair of mini-glaciers is that the emerging moraine that divides them from the main glacier also divides their outflow. They feed a separate branch of the White River from the main stem – another argument for recognizing these glaciers as discrete, perhaps?

It is logical to assume that these little glaciers are doomed by the same forces of climate change that created them, but there is a twist that just might keep them flowing — and perhaps thriving — as a result of climate change. While scientists believe that snow levels will rise in the Cascades over the next century, they also believe that precipitation will increase.

That could mean that in the highest elevation areas where winter precipitation still falls mainly as snow could actually see glaciers grow in depth, but perhaps not in length, since freezing levels would be higher. Therefore, if these mini-glaciers are high enough on the mountain, they may well survive, or possibly even grow, thanks to increased snowfall at this elevation.

If these glaciers are new, and independent of the White River Glacier, they deserve some respect, since all known glaciers in Oregon have been formally named. And that brings us to a bit of history surrounding this flank of the mountain. For here, on the upper slopes above these little glaciers, the first attempts on Mount Hood’s summit were made by early white settlers.

A close-up view of the mini-glaciers reveals classic crevasses

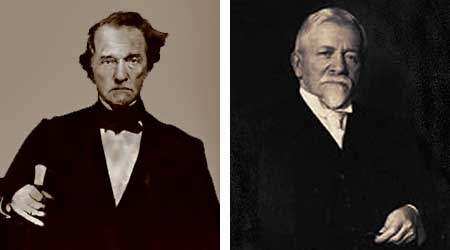

The first man in this story is Thomas Jefferson Dryer, the colorful publisher of the Weekly Oregonian in the mid-1800s (pictured below, on the left). Dryer claims to have been the first white man to climb the mountain, in August 1854. Dryer’s description of the climb makes it clear that he did not reach the true summit, though he may well have reached the top of the Steel Cliffs, only a few hundred feet below the summit — and an amazing achievement for the day.

Dryer complicated his case by embellishing the story with outrageous exaggerations — being able to see Mount Shasta (not possible) and peaks in the Rockies (definitely not possible), and his climbing companion bleeding form his skin from the extreme altitude (not very likely). But Dryer was also the first white man to climb Mount St. Helens, so his story must be taken with some degree of faith.

Dryer’s account wasn’t challenged until three years later, when one of his employees, Henry Lewis Pittock, made the first documented ascent of Mount Hood on August 6, 1857. The Pittock party made the climb along what is now the traditional southern route, skirting the west edge of the White River Glacier, and climbing through the crater. When Pittock’s party made claim to being the “first” to summit the mountain, it set off a dispute with Dryer over the veracity of his own account that continues to this day.

Thomas Jefferson Dryer (left) and Henry Lewis PIttock

In 1861, Dryer was tapped to serve in the Lincoln administration, and turned the Weekly Oregonian over to Pittock, to whom he owed a significant debt in the form of back pay. Pittock, in turn, converted the weekly into a daily and was soon publishing the predominant newspaper in the region, today’s daily Oregonian.

Pittock is now recognized as the first white man to summit Mount Hood, but like Dryer, doesn’t have a landmark in his name to record his place in history (though Portlanders are quite familiar with the iconic mansion he built atop the West Hills).

So I offer a modest proposal: honor both men for their historic climbs, with the western mini-glacier (1) named for Pittock, representing his more westerly approach, and the eastern mini-glacier named for Dryer, who may have even walked on this ice sheet in his own attempt at the summit. Both men deserve to be remembered for their part in Mount Hood’s history, and these little glaciers deserve some respect, too.