1920s postcard view of the Shepperd’s Dell Bridge and its iconic Douglas fir (colorized for this article)

A reader reached out a few weeks ago with a question about “that big fir tree at Shepperd’s Dell, and as it turned out, I had been working on an article on that very subject! The tree in question is unmistakable: it stands near the east end of the iconic Shepperd’s Dell Bridge, perhaps the most recognizable of the many graceful bridges along the Historic Columbia River Highway.

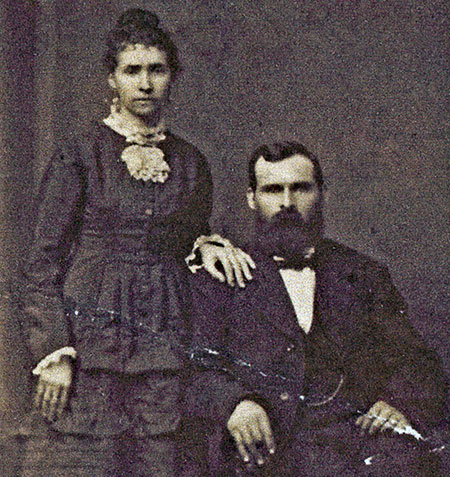

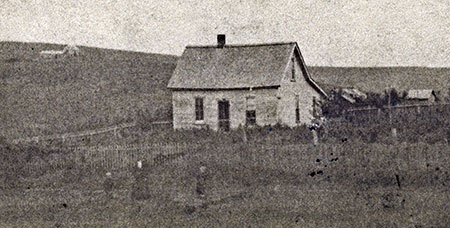

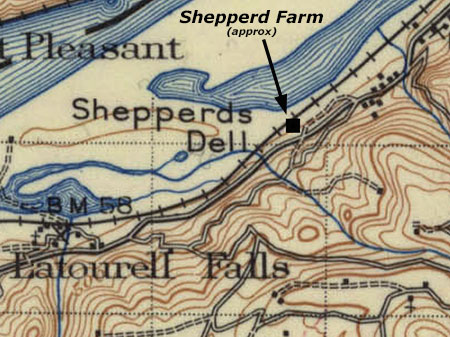

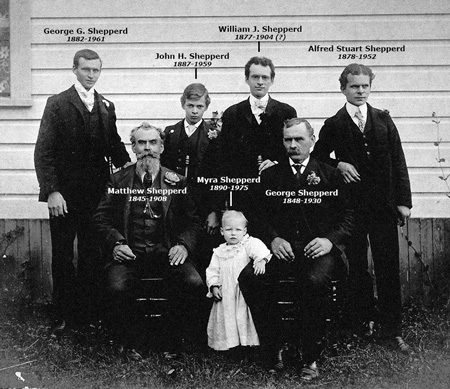

The big tree is a Douglas fir, Oregon’s official state tree, and it has been growing here since well before this section of the historic highway was constructed in 1914. The tree grows in a protected hollow, surrounded on three sides by basalt cliffs. George Shepperd, the local farmer who donated what is today’s Shepperd’s Dell State Natural Area to become a park, walked under the tree with his family on their regular visits to visit the waterfalls at Shepperd’s Dell from their farm, located just to the east. Today, countless visitors admire it from the shady wayside at the east end of the bridge.

1910s view of the west approach to Shepperd’s Dell with the big fir rising in front of Bishops Cap

Early photos of the new Shepperd’s Dell Bridge taken in the late 1910s (above) show the tree prominently framing the rock outcrop known as Bishops Cap, more than a century ago. At the time, the tree was large enough to easily be 60-70 years old, though it still had the symetrical shape of a relatively youthful tree.

The image below shows the 1910s scene in reverse, from atop Bishops Cap, with the big Douglas fir standing out in the foreground and a few early motorists parked along the opposite side of the highway.

1910s view looking west from the top of Bishops Cap toward Shepperd’s Dell Bridge, with early motorists and the big fir front and center at the east end of the bridge

This hand-colored postcard (below) from the 1930s features Bishops Cap, and the big Douglas fir is especially prominent in this view. The construction of Historic Columbia River Highway was famously designed to blend with nature and follow the contours of the land, but that still required road engineer Samuel Lancaster to do some fairly heavy blasting and grading to complete the scenic route. At Shepperd’s Dell, he graded the slope above the big fir, but clearly took care to protect the tree from fill debris, likely extending its life for another century.

1930s hand-tinted postcard view of Bishops Cap with the big fir prominently featured to the left

Here’s another hand-tinted 1930s postcard view (below) from the west end of the Shepperd’s Dell Bridge showing Bishops Cap and the big fir. When I first came across this image, I assumed that a fair amount of artist’s license was used to create the scene, since it appears to be from a point in space, where a vertical cliff drops directly below the historic highway.

1930s hand-tinted postcard view of the Shepperd’s Dell Bridge and the big fir in the upper left

However, I eventually came across the 1920s era photo (below) that the previous, hand-tinted image was created from. It turns out the photographer was part mountain goat and managed to capture the scene from a vertical slope below the old highway! As in the hand-tinted view, the big Douglas fir rises beyond the bridge, on the left.

This is the 1920s photograph that the previous hand-tinted scene was based upon, with the big fir in the upper left

This 1910s view (below) is perhaps the most popular of the early images of the Shepperd’s Dell Bridge. It appeared in both its black and white original form and in colorized versions on countless postcards and in souvenir folios that were popular with early motorists visiting the Gorge. At the time this photo was taken, many sections of the new highway were still unpaved, including the section at Shepperd’s Dell.

This is perhaps the most popular 1920s postcard view of Shepperd’s Dell Bridge, with the big fir on the left

Over the century since Samuel Lancaster built his iconic highway through the area, the big fir at Shepperd’s Dell has thrived, as shown in this pair of images (below). The arrows provide reference points on Bishops Cap that helps underscore just how much the old fir has grown in just over century when viewed from the same spot at the west end of Shepperd’s Dell Bridge.

A century passed between these views, but the big fir remains and has grown noticeably larger — the 2021 view is somewhat wider than the 1920s view to fully capture the big fir!

[click here for a larger version of this comparison]

In the 1920s view, the top of the big fir was visually just a big higher than the top of Bishops Cap. By 2021, the tree had not only added some 50 feet to its height, it had also spread out and formed a more rounded crown that is typical for mature Douglas fir. The upper arrow in the 2021 image points to what was the approximate top of the tree in the 1920s. The spread of the tree is noticeable in the 2021 image, as well, as it now obscures part of Bishops Cap from this perspective.

The big fir at Shepperd’s Dell after the fire..?

The charred base of the big fir at Shepperd’s Dell in 2018, one year after the fire

Today, the Shepperd’s Dell fir remains a familiar feature to those stopping at the wayside, a true survivor that stands out from the surrounding forest. Its stout trunk is much larger than other trees in the area, and there has always been a bit of a mystery about a plank attached to the tree and metal cable that disappears into the canopy (I won’t attempt to solve that in this article!). So, when Eagle Creek Fire swept through the Gorge and reached Shepperd’s Dell over Labor Day weekend in 2017, the fate of this old tree was on my mind.

In the immediate aftermath of the fire, it was clear that the big tree hadn’t crowned (meaning the fire hadn’t engulfed the entire tree), but a significant part of the crown had been scorched and the bark at the base of the tree was badly blackened. The understory around the tree was completely burned away, so it was clear the fire had burned hot when it swept through. Because the fire occurred toward the end of the growing season, when conifers are becoming dormant with the approach of winter, it was impossible to know if the living cambium layers under the big fir’s thick bark had been destroyed by the heat of the burn. That would have to wait until the next spring, when the stress of producing new growth would test the its ability to survive.

By the fall of 2018 — one year after the fire – the situation was discouraging. The old tree had put out very little new growth on its remaining green limbs in its first growing season after the fire. And while it retained many of its surviving limbs over the course of that year’s summer drought, many had dropped their needles and died back (below), leaving the tree with less than half its canopy intact. Still, it had managed to survive the first year following the fire.

Looking up at the badly scorched canopy of the big fir in 2018, one year after the fire

The group of younger Douglas fir around the big tree didn’t fare as well. Some had been immediately killed by the fire, while others that survived the initial blaze seemed to have lost too much living canopy to recover from the fire (below). During that first summer, the combined loss of green canopy and stress from the annual drought season was too much for many of these trees to survive their first year after the fire.

The scorched big fir and its smaller companions in 2018, one year after the fire

As the big fir at Shepperd’s Dell entered its second winter season after the fire in 2018-19, it wasn’t looking good at all. It has put on almost no new growth that year, and the annual needle drop that fall left even more blackened, bare limbs exposed.

Worse, the Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) was cutting down what it deemed to be hazard trees along the historic highway in the wake of the fire. This included scores of trees around Shepperd’s Dell, some of them living trees that were impacted by the fire, but still surviving. Its haggard appearance at the time (below) put the big fir at great risk of being defined a “hazard” by highway crews, but thankfully, it was spared from the chainsaws.

The Shepperd’s Dell fir in 2019… with less than half its canopy intact, the old tree was still hanging on…

Then, in the spring of 2019, the big fir pushed out a modest flush of new growth on its surviving limbs in its second season of growth following the fire. It wasn’t much, but it did signal that the tree was finally starting to rebound from the fire. It was no longer losing ground in its recovery.

As the spring of 2020 unfolded, our world seemed to stop as the COVID pandemic swept the globe, but for the big fir at Shepperd’s Dell, things were clearly looking up. The tree put on another flush of new growth in its third year following the fire, then another flush of new growth followed in the spring of 2021. While we hunkered down in the pandemic, the big fir was making its comeback (below).

The big fir makes a comeback: three growing seasons between these images show significant recovery of the crown and middle canopy

[click here for a larger version of this comparison]

Looking up into the canopy in 2021, the change in just three years of gradual recovery is dramatic (below). The big fir has been rebuilding its living canopy and thereby restoring its ability to actively grow, once again. Surprisingly, some of the new growth was also emerging from limbs that seemed to have been lost in that first year after the fire, but apparently had just enough living cambium layer left to allow new growth to emerge through the blackened bark.

Looking up into the recovering canopy of the big fir in late 2021

Today, the future of the big fir at Shepperd’s Dell seems much brighter. Its recovery is remarkable, considering how many of its neighbors were lost to the fire (below). But that’s no accident. Our largest conifers — Douglas Fir, Ponderosa Pine and Western Larch — typically drop their lower limbs as they grow. This adaption focuses growth at the top of their canopies, where they can absorb the most sunlight, but it also helps protect their living crowns when fires sweep through by denying a “ladder” of lower limbs that allow fire to climb up the tree to the main canopy.

Low intensity fires reinforce this adaptation, with the lowest limbs of moderately burned trees often succumbing to the fire, even as the tree survives, placing its crown still further above the reach of future moderate intensity burns. These “cool” fires are beneficial, helping thin the forest, remove accumulated fuel, invigorate the leafy understory and allow the largest trees to live on to continue anchoring the forest. Combined with thick, fire-resistant bark, these big conifer species define the “fire forests” along the east slopes of the Cascades, where fire is an essential part of the ecosystem, though Douglas Fir grows throughout the Cascades.

The big fir survives! But some of its companions did not…

While some of the area burned in the 2017 Eagle Creek fire fit the definition of “beneficial”, vast areas burned far too hot for any trees to survive, requiring whole ecosystems to restart from bare soil, and in turn, exposing bare soil to serious erosion. Today, modern forest management is increasingly embracing prescribed burns with moderately hot fires to mimic the frequent beneficial burns that were common before modern fire suppression began in the early 1900s. While still controversial for the risk that prescribed burns can potentially bring to rural property, their overwhelming benefit to the forest and role in preventing catastrophic fires is unquestionable.

Look closely at the burn patterns following the Eagle Creek Fire, and you will also see big conifers growing in moist canyons or shaded north-facing slopes were more likely to survive the fire. This has to do with the timing of the blaze. When the fire swept through over Labor Day weekend in 2017, Oregon’s forests were at their most stressed point in the growing season, with several months of drought and hot weather drying trees out and making their extremely vulnerable to fire.

Yet, trees with better access to moisture during the annual drought cycle are able to stay fully hydrated, and are much less vulnerable to the intense heat of a forest fire. This is also why some of our largest trees are found where summer moisture is available. Look at the bark on many of these trees, and you are likely to see ancient burn marks, often from multiple fires that these trees have survived over their long lives. As our forests cope with a changing, warming climate, these conditions favorable to survival will become increasingly important if we hope to continue to have big trees in our forests.

Aerial view of Shepperd’s Dell from 2019 showing the historic highway curving gracefully around the shaded hollow holding the big fir (ODOT image)

What does the future hold for the big fir at Shepperd’s Dell? In the near future, this old tree suddenly has less competition for water and nutrients from nearby trees that succumbed to the fire. For the longer term, it enjoys an excellent location for survival, growing in a shaded, moist bowl surrounded by protective cliffs that buffer it from the seemingly perpetual Columbia Gorge winds.

Douglas fir can live for centuries, and there’s no reason this old tree can’t outlive every human being walking on the planet today – and their children and grandchildren, too! Its most lethal threat is probably us. So, hopefully we will continue to give it the respect and space to grow that Sam Lancaster provided with his curving highway design more than a century ago, allowing many future generations to marvel at this old survivor, just as we do.

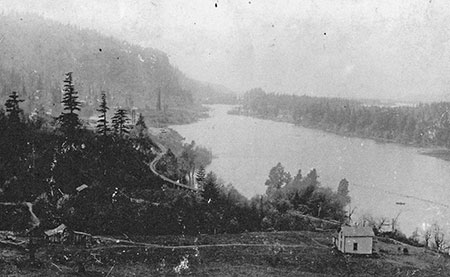

Previous WyEast Blog articles on the remarkable George Shepperd: