Eagle Creek Fire during the initial, explosive phase (US Forest Service)

Officially the Eagle Creek Fire in the Columbia River Gorge is still fully involved, now at 35,000 acres and just 10 percent contained by firefighters. Rain in the forecast for the coming week suggests that the fire will continue to slow as October approaches, and our attention will turn toward the changes that fire has once again brought to the Gorge.

The Gorge is a second home for many of us, and in some ways the fire was akin to watching our “home” burn. But that’s a human perspective that we should resist over the long term if we care about the ecological health of the Gorge. Fire is as natural and necessary as the rain in this amazing place, though that’s a truth that we have been conditioned to resist. I’ll post more on that subject in a subsequent article.

Surreal Gorge landscape under smoky skies from the Eagle Creek Fire (US Forest Service)

For now, we’re just beginning to learn about the impact of the fire, even as it continues to burn. Thankfully, no lives have been lost, no serious injuries reported and very few structures have been lost. That’s a testament to our brave emergency responders (many of them volunteers) and the willingness of most Gorge residents to abide by evacuation orders. It has surely been a frightening and stressful time for those who call the Gorge home.

The impact on public lands is still largely unknown, but the Oregon side of the Columbia River Gorge has one of the most concentrated, most heavily used trail systems in the world, and the damage to trails is likely to be significant. The Forest Service is likely to close affected trails for months or even years in order to assess the damage and determine how best to restore them.

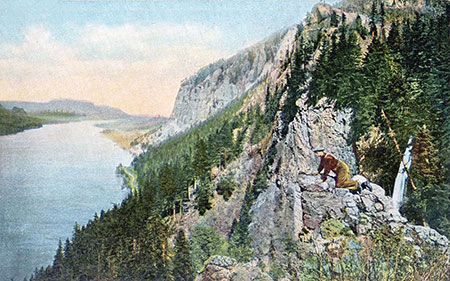

1930s hiker at a viewpoint along the Perdition Trail (with Multnomah Falls beyond)

If you’ve lived here for awhile, you’ll also recall that we lost the Perdition Trail, an iconic, prized connection between Wahkeena Falls and Multnomah Falls, to the 1991 Multnomah Falls Fire. The reasons were complex, and it will tempting for the Forest Service to let some trails go, given their shrinking trail crews. We should not allow this to happen again.

Every trail should be restored or re-routed, and new trails are also needed to spread out the intense recreation in the Gorge. Trails advocates will need to work together to ensure this. Trailkeepers of Oregon (TKO) has set up a mailing list dedicated to Gorge trail restoration, if you’re interested in working on future volunteer projects. You can sign up for periodic updates and events here.

______________________

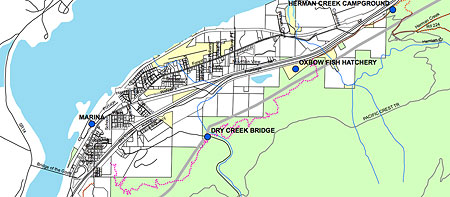

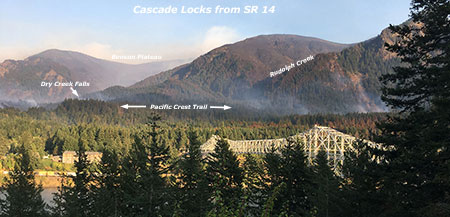

On September 10, I drove SR 14 on the Washington side of the Gorge for my first look at the fire, starting in Hood River. Below each of the following annotated photos, I’ve linked to much larger versions that I encourage you to view if you’re reading this on a large monitor, as they provide a better sense of the fire’s impact.

As hoped, much of the burn is in a patchy “mosaic” pattern, a healthy and desirable outcome for the ecosystem. This is how fires used to occur in our forests, before a century of suppression began in the early 1900s. Mosaic burns allow for mixed forest stands and exceptional wildlife habitat to evolve, even as we might mourn the loss of familiar green forests.

The wind pattern on Sunday had shifted from westerly to a northwesterly direction, producing a bizarre effect: smoke from the fire hugged the vertical wall that is the Oregon side of the Gorge, while the Washington side was cleared of smoke and under a bright blue sky. The view, below, shows this split-screen effect from near Wind Mountain.

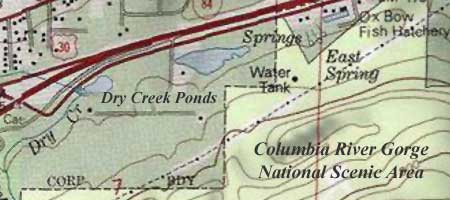

Moving west, the combination of ongoing wildfire and back-burning by firefighters was producing a continuous plume along the base of the Oregon cliffs, from Herman Creek east to Shellrock Mountain, as seen below. The Pacific Crest Trail traverses this section, and is undoubtedly affected by the fire.

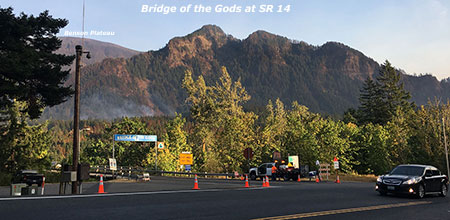

From the Bridge of the Gods wayside, opposite Cascade Locks, the impact of the fire on the canyons that fan out from Benson Plateau is visible. Some areas (below) show a healthy mosaic burn, while some of the upper slopes show wider swaths of forest impacted. The alarming proximity of the fire to the town of Cascade Locks is also evident in the scorched trees visible just above the bridge in this view. This was a close call for those who live here.

Turning further to the east from the Bridge of the Gods wayside (below), the ongoing wildfire and back-burning shown in the previous photos can be seen in the distance, beyond the town of Cascade Locks.

The scene at the Bridge of the Gods bridgehead (below) is an ongoing reminder that we’re a long way from life returning to normal for Cascade Locks residents. For now, I-84 remains closed and this is the only route into town, and only open to those with proof of residency.

Moving further west, the 2000-foot wall of cliffs in the St. Peters Dome area that stretches from McCord Creek to Horsetail Creek (below) come into view.

Here, the fire has also burned in mosaic pattern, with many patches of green forest surviving. But the frightening effects of the firestorm that occurred in the first days of the fire is also evident, with isolated trees on cliffs hundreds of feet above the valley floor ignited by the rolling waves of burning debris that were carried airborne in the strong winds that initially swept the fire through the Gorge.

A second view (below) of the St. Peters Dome area shows the burn extending toward Nesmith Point, nearly 4,000 vertical feet above the Gorge floor.

Moving west along SR 14 to the viewpoint at Cape Horn, the impact of the fire on areas west of Horsetail Falls comes into view (below), along with a better sense of the mosaic pattern of the burn. This view shows the Horsetail Creek trail to be affected by the first, as well as the slopes on both sides of Oneonta Gorge.

In this earlier piece on Oneonta Gorge, I described the dangerous combination of completely unmanaged visitor access and an increasingly dangerous logjam at the mouth of the Gorge. The fire will almost certainly trigger a steady stream of new logs rolling into Oneonta Gorge and adding to the massive logjam in coming years.

Moving further west, the area surrounding iconic Multnomah Falls and Wahkeena Falls comes into view (below). As with other areas, the fire burned in vertical swaths along the Gorge face, leaving more mosaic patterns in the burned forest. From this view, trees along the popular 1-mile trail from Multnomah Falls Lodge to the top of the falls looks to be affected by the fire, as are forests above Wahkeena Falls.

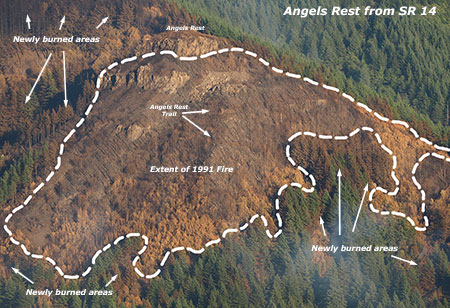

This wide view looking east from above Cape Horn (below) shows most of the western extent of the fire, with the north-facing slopes of Angels Rest heavily burned, while the west and south-facing slopes were less affected.

A closer look at Angels Rest shows that the burned area in the current fire closely matches the area that burned in the 1991 (below), along with slopes on the opposite side of Coopey Falls. The Angels Rest Trail was heavily impacted by the 1991 fire, and will clearly need to be restored after this fire, as well.

I’ve marked an approximation of the 1991 fire extent at Angels Rest in this closer look (below) at the summit of Angels Rest, based on tree size. Tall conifers burned in today’s Eagle Creek fire survived the 1991 fire, and mark the general margins of that earlier fire.

Areas within the 1991 burn were still recovering and consisted largely of broadleaf trees, like Bigleaf and Vine maple. Depending on the heat of the fire and whether their roots survived, these broadleaf trees may be quick to recover, sprouting from the base of their killed tops as early as next spring.

The recurring fires at Angels Rest offer an excellent case study for researchers working to understand how natural wildfires behave in successive waves over time. This, in turn, could help Gorge land managers and those living in the Gorge better plan for future fires.

Finally, a look (below) at the western extent of the fire shows a few scorched areas in Bridal Veil State Park, including the forest around the Pillars of Hercules. Bridal Veil Canyon appears to have escaped the burn, though some trees near Bridal Veil Falls may have burned.

I’ve titled this article as my “first look” because the story of the Eagle Creek fire is still being written. Only after the fall rains arrive in earnest will we have a full sense of the scale of the fire.

As new chapters in the Eagle Creek saga unfold, I’ll continue to post updates and share perspectives on this fire and our broader relationship with fire as part of the natural systems that govern our public lands. With each new fire in close proximity to Portland, we have the opportunity to expand and evolve how we think about fire, and hopefully how we manage our public lands in the future.

More to come…